In the pre-army academies, a new approach to Jewish learning is taking hold—one that American Jewish institutions would do well to learn from.

As the lines between Jews of different denominations in the U.S. are becoming more rigid and stratified, many have begun to wonder if Jewish life is an all-or-nothing proposition. We have begun to ask ourselves some distressing questions: In order to study Judaism and its fundamental texts, must one live a religious life in a particular mode? Do alternative possibilities exist? Can a woman find a place to study Talmud wearing pants? Is there room for a man to study and teach bare-headed? Can religious people learn from their secular peers, or vice-versa?

Like everyone else, I have struggled with these questions; and I have often wondered if Israel might provide an answer: Since Judaism is the majority culture in the Jewish state, religious, secular, and those in between might have a sense of security that allows for individual and communal approaches to religion that don’t exist elsewhere.

I’m not the only one. This past fall, delegations from the General Assembly of the Jewish Federations of North America visited ten different institutions of Jewish learning around Jerusalem hoping to find new ways to reach out to Jews of all lifestyles and denominations.

On a trip to Israel in January 2014, I hoped to examine some of these issues by visiting a variety of institutions in which secular and religious people study together. They promote the idea that Jewish texts and values belong to all Jews rather than one specific denomination, and can be understood and applied by both those who live a religious life and those who do not. I discovered that, while the process is often complicated and sometimes difficult, Israel is learning to strike a balance between secular and religious approaches to Judaism. Moreover, it is doing so not only in private institutions, but also in such public arenas such as the Knesset and Israeli television.

My experience with these issues goes back a long way. When I was studying at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1990-91 prior to beginning a PhD program, I wanted to find a way to combine my academic study of the Bible and Midrash with a kind of learning that was more from the kishkes; I sought something that was also about inspiration and spirituality.

I tried a class on the weekly Torah portion at a Jerusalem girls’ yeshiva, taught by a rabbi with an Ivy League PhD who was known for his love of modern art. But I was completely alienated when he said that getting a PhD was a waste of time for anyone.

I don’t remember precisely how it happened, but I heard about a fledgling institution called Elul. As a result, I ended up studying one night a week with teachers Melilla Hellner-Eshed and Rotem Prager-Wagner. The topic was “images of Elijah the prophet,” and we went through everything from biblical images of Elijah to rabbinic literature and mysticism to modern Hebrew poetry. The diversity of the texts we studied, the mix of students from different backgrounds, and the fact that I was the only English-speaker there was profoundly appealing to me. This eclectic and pluralistic approach to Jewish study was described in an article in Eretz Acheret magazine as “barefoot learning.” Its purpose is to foster intentional learning, shorn of outside mediation—just the student meeting the text. This is meant to enable all students, secular and religious, to approach the text together, without the feeling that some have an advantage over others. One of the founders of Elul, Gera Tuvia, explained,

People gave themselves the freedom to express their emotional responses to a text. The individual’s direct contact with the text became an important element and this element bolstered the secular Jews’ self-confidence: Your encounter with the text is not like learning a foreign language. You can approach the text and begin conversing with it; the text will teach you how to speak with it. You do not need a mediator. You can call this audacity, arrogance. Those who continued really learned, while those who did not continue were perhaps left with an illusion. For the religious Jews, this was an enormous, powerful liberation—the ability to rediscover texts that you think you are already familiar with, the ability to react in different ways, the ability not to love, the ability not to receive, et cetera.

One of the things I found so striking at Elul was that both secular and religious people had equal access to the text. Even though the religious students might have been more familiar with Talmud and Midrash, the secular students were able to bring a different perspective to them. Everyone agreed that we could learn from each other. This was a very different experience from the hierarchical atmosphere of university study. I felt this was a kind of learning that could only exist in Israel. I was fortunate to have experienced it, and wished it could be imported to the U.S.

Elul is still going strong. When I interviewed its new director, Shlomit Ravitzky Tur-Paz, during my latest trip, I asked about her vision for the institution. “The future of the Torah,” she said, “is being able to understand that each one has his own choices and abilities.” The daughter of Hebrew University professor of philosophy Aviezer Ravitzky, recipient of the 2001 Israel Prize, and Ruth Ravitzky, who edited a book on readings of Genesis by Israeli women, Tur-Paz grew up in a religious home. Yet she acknowledges that she can learn from secular people because there is value in different “worlds of knowledge,” brought together by people with different backgrounds. This belief is reflected in Elul’s dizzying variety of programs, which seek to integrate religious and secular Jews from all ethnic backgrounds.

Many of these programs are strikingly innovative and unusual. For example, Tur-Paz believes that a relationship with the arts is “something essential. We like people to see Jewish sources as inspiration for their creativity.” This approach, she says, “enriches the Torah and the sources and it can bring new interpretations to the Torah”; which furthers the goal of making the Torah “wider and richer.”

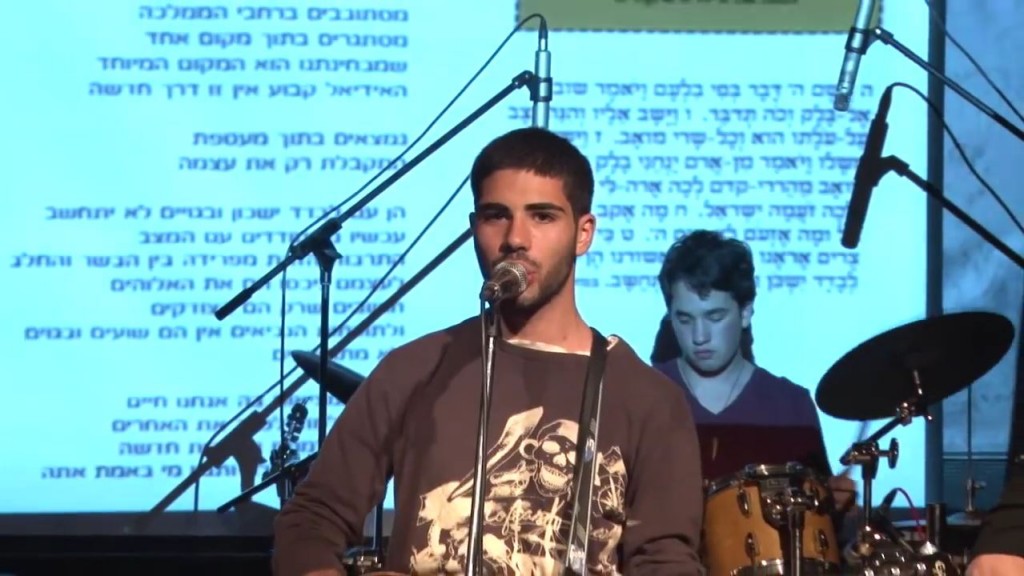

To that end, Elul has programs for storytellers and musicians as well as more conventional students. One of the most inventive is “Mekorock” (a portmanteau of “rock ‘n’ roll” and “mekor,” the Hebrew word for “source”), a program for 15- to 18-year-old musicians in which they study texts and then write their own songs inspired by them. Major Israeli artists come to work with the students, such as Aya Korem, Idan Haviv, David Lavi, Ariel Horowitz (son of iconic singer Nomi Shemer), and the popular band Shotei Ha’nevuah. The musicians speak with the students about their own work and help organize a siyum—the traditional celebration of finishing a course of study—at the well-known rock venue Yellow Submarine.

Another arts-related program at Elul is the storytelling project. While I talk with Tur-Paz, the program is holding court in an adjacent room. I hear singing, then shouting. I ask my hosts what is going on and they shrug. The noise is “part of the training. They’re rehearsing a story.” After our interview concludes, Tur-Paz accompanies me to the classroom to see actors, teachers, and storytellers studying texts in order to adapt them into a theater piece for children. The idea is that children can be exposed not just to Little Red Riding Hood and Cinderella, but also stories from the Talmud, whose “issues are Jewish stories.” Like the Mekorock project, the program is split between studying texts and discussing how to present their ideas to an audience. The teacher is clearly talented, circling the group, using her body to gesture at her mostly middle-aged students, leading them in the song “Leila, Leila,” based on a poem by revered Israeli poet Nathan Alterman.

These programs are not limited to Elul’s Jerusalem campus. There are 25 different groups meeting once a week to study subjects like the Bible, Talmud, emotions in Jewish sources, food in Jewish culture, various Hasidic rabbis and their world, and environmental issues in society.

The next day, I head to Kfar Adumim, outside Jerusalem, to visit the Ein Prat mechina (or preparatory) program. Established in 2001, Ein Prat consists of a 10-month first-year track, a six-month second-year track, and a Zionist midrasha that holds programs for visiting groups.

This particular afternoon is devoted to the issue of Jewish identity. Coincidentally, Shlomit Ravitzky Tur-Paz is the designated speaker. She tells the students about herself and her attitudes to identity and pluralism. One of the things she shares is a joke: When one enters a mechina program as hiloni [secular], one comes out “datlash.” I ask the young man next to me what datlash means. He tells me it stands for dati le’she’avar—“formerly religious.” It takes me a while to figure it out, but I realize Tur-Paz is saying that the only difference between a hiloni and a datlash is that of consciousness of identity. A person with a hiloni background who spends a year at a mechina program will come out with an understanding of religion similar to those who grew up with it, even if neither is currently practicing.

After Tur-Paz speaks to the group, I watch Dr. David Nachman, head of the first-year track, in action. He gives the students an “identity quiz,” with questions like “Are you a Jew? An Israeli? A human being? Is a Jew someone who fights anti-Semitism? Was born a Jew? Converted according to Jewish law? Someone who feels Jewish?” He also teaches them material prepared by the Israel Democracy Institute about Israel’s Law of Return, Shabbat, and Jewish holidays.

Nachman’s background is as eclectic as the material he teaches. Nachman is 44 years old and holds a PhD in Jewish law; he began his education studying at an field school in Kfar Etzion, moved on to a religious-Zionist yeshiva in Kiryat Shmona, served in the IDF, and took a variety of teaching jobs at both secular and religious institutions.

In his modest office, Nachman tells me a little about the history of the mechina movement. The mechinot, he says, were started in the town of Eli by rabbis concerned that students were “losing their kippot” during army service. They wanted to create a pre-army program that would strengthen their religious identity. After the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, secular educators started to join in. They felt the need to bridge the gap between religious and secular Zionists by having students spend a year studying, volunteering, and asking big questions like “Who am I? Why do I serve in the army? What is it to be a Jew and to have a Jewish state?”

Ein Prat is highly selective. Only 50 students are accepted from hundreds of applicants. Half are male and half female; a third are religious, a third secular, and a third somewhere in the middle. In potential students, Nachman is looking for a “gleam in the eye” and “boys and girls doing something in life—volunteering, going to youth group—interesting people, not boring”; who will try to “push borders all the time.” For example, the entire mechina is preparing to run a half-marathon in Jerusalem, and has a project to get students to read the entirety of the Hebrew Bible—two chapters a day over the course of a year. The purpose of these activities? “We are trying to challenge them in all aspects of life.”

Nachman also wants the students to grow as a group. For instance, they study the Sabbath through sources from the Bible to early Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am to modern government reports in order to “decide how to do Shabbat together.” There are rules for public places and for each individual caravan in which the students live. Nachman sees all this as “creating a new kind of Israeli Jewish identity above the question of how many mitzvot you keep,” a “more holistic” view of religion.

Israelis are finding fascinating new ways to strike a balance between secular and religious approaches to Judaism.

Ultimately, he hopes that when his students and alumni go on to the army and university, they will “create a movement.” He wants them to “speak a new language, sit together” and know the importance of “being responsible and doing good.” His students, he says, “want to meet the other. The religious have a lot to learn from the secular, and the opposite also.” On a personal level, he “can’t imagine my life, my family without this” open-mindedness and interaction with all types of Jews. “My older boys are in yeshiva,” he says. “I can allow it because they see what happens here, so they are not close-minded.”

I spoke with a student named Noa Ganot, who echoed Nachman’s ideals when she told me why she decided to come to Ein Prat. Her older brother had been in a mechina program, and though she heard him talk about “how amazing” it was, the “change in him” was even more powerful. “He matured,” she said, “became more self-aware, aware of society and other people.” I’ve talked to a number of parents whose children have attended mechinot. They all agree that the students take on a different level of responsibility after their first year.

Growing up in a religious home with no secular friends, Ganot knew nothing of the secular world. Though she always thought secularism was a “lack of religion,” her experience at Ein Prat taught her this was false. “They have a framework,” she said, and there is “a lot to it.” She is grateful for the opportunity to get to know young people “from the whole country,” and hear “different opinions” from the “crazy variety of people here…. I wish every teenager could do this.”

But outside the cocoon of the mechina all is not rosy between religious and secular Israelis. Professor Yair Zakovitch, the Father Takeji Otsuki Professor of Bible Emeritus at Hebrew University, is a secular Jew committed to Jewish learning, but when I interviewed him, he expressed his worries about the future of secular Jewish culture. Young secular Israelis, he says, “take the state of Israel for granted,” while his generation was suffused with the sense that Israel’s existence is miraculous. There are times, he told me, when he looks out the window of his Mount Scopus classroom and sees the Temple Mount; then he stops teaching and tells his students, “Look out there. You are so lucky. You are studying the Biblical text in Hebrew in the place it was created. How many other people share this experience?”

Zakovitch started a program called Revivim, to encourage creativity in teachers of Bible on the high school level and thus promote more interest in the Bible among the younger generation. He speaks of the program as one that is “difficult to get into like the elite special forces units of the army,” giving it prestige. Students learn to teach creatively and to cooperate with the art, music or literature teachers in their schools. He knows this program to train teachers is successful because it already has a second generation of students studying to be teachers; and there is a similar program at Tel Aviv University. This gives him hope, since he sees the competition as “very good” for both programs. “On the one hand,” he says, “I am a pessimist and complain too much,” since Revivim is a success and a book he co-wrote with Midrash professor Avigdor Shinan on the Bible has been a bestseller in Israel. Called Lo Kach Katuv Ba’Tanach, it was translated into English by his American wife Valerie as From Gods to God: How the Bible debunked, suppressed, or changed ancient myths and legends.

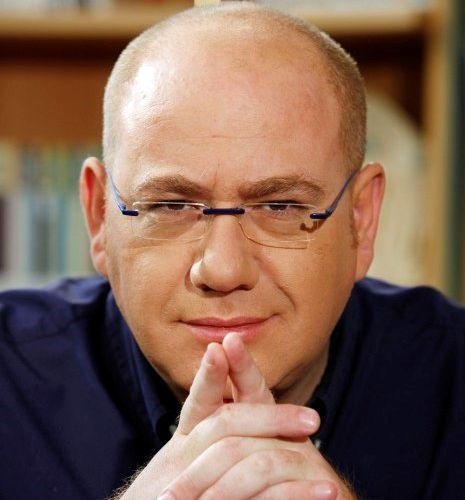

Dov Elbaum, host of the TV show Mekablim Shabbat (“Welcoming Shabbat”). Photo: Sasson Tiram / Wikimedia

Yet Zakovitch also recounts a troubling recent experience. He and Avigdor Shinan, who is religious, often teach together; on this occasion, a religious man came up to Shinan, pointed his finger, and asked how he could possibly teach with a secular person. The pain in Zakovitch’s voice speaks to the sadness he feels at Israeli society’s lack of tolerance; he thinks the religious-secular divide is widening. What worries him most, he says, is that “many of my friends are religious,” and there is a “difference between them and their children.” While dialogue is possible with religious people of his generation, he worries that “my children will not be able to have a dialogue with their children.”

Zakovitch’s answer to this is also his life’s work: getting secular Jews to read the Bible, “not to give up on it.” He recounts a recent trip he took to Mount Gilboa, where he read David’s lament over the deaths of Saul and Jonathan. To read the passage in the location where it took place brought tears to his eyes. “That’s why I am so devoted,” he says. He sees his “study of the Bible as an expression of my Zionism” and asks, “How can one be a Zionist without having this knowledge?”

To him, the desire to live in Israel is deeply connected to an understanding of Jewish culture. Zakovitch can’t understand people who say they are “Israeli first and then Jewish.” He quips, “Being Israeli without Jewish culture is hummus.” He does love hummus, he hastens to add, but it is not “what keeps me here.” It pains him to see so many Israelis leaving for the U.S. and even Berlin. For “anybody to leave,” he says, “for a young Israeli to leave, is painful for me. We are still a young country; we have built this country, the generation of my parents; all of sudden these young people don’t care anymore.” He feels that the only choice Israelis have is “your Bible or your passport,” and hopes that more study of the Bible and Jewish culture will help convince young Israelis to remain at home and connected to the country and its culture.

Despite Zakovitch’s worries, there are many Israelis who are bringing their knowledge of the Bible and other Jewish texts into mainstream Israeli society. Dov Elbaum, for example, is a teacher and writer who was called a “hiloni rebbe” in a 2007 Jerusalem Report profile. The piece came out in conjunction with the publication of his spiritual autobiography, now translated as Into the Fullness of the Void: A Spiritual Autobiography. He tells me that he sees himself as a “spiritual leader, not a professor,” because “when I teach Zohar,” the central text of the Kabbalah, “I am so deeply involved.”

The youngest of nine children raised in a Yiddish speaking ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem home, Elbaum is now a television writer and broadcaster. His Friday night program Welcoming Shabbat combines his two passions: “To speak and interview, and to speak about the Torah portion.” He feels that he has been successful because “people who don’t do anything accept Shabbat with my show…. Before my show nobody in secular Israel wrote about parshat hashavua [the traditional weekly Torah reading]. All big platforms, Israeli internet, every big website, now has parshat hashavua.”

When he left the religion of his youth, Elbaum wanted to find a way to bridge secular and religious culture. He is now “very proud” of his show, because he feels it has accomplished precisely that. And like Zakovitch, he is convinced that “Israel cannot exist without Jewish texts. It is the base of Israel, the foundation of our being here.”

Ruth Calderon speaks during Kabbalat Shabbat services at the port in Tel Aviv, August 15, 2008. Photo: Miriam Alster / Flash90

Another teacher of rabbinic ideas is not just able to reach people, but also create laws inspired by Jewish texts. Member of Knesset Ruth Calderon holds a PhD in Talmud studies from Hebrew University, helped start Elul with Melilla Hellner-Eshed, and then moved on to found Alma, a pluralistic seminary in Tel Aviv. Her first book to be translated into English is the accessible A Bride for One Night. Swept into the Knesset with Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid party, Calderon told me that, in all her work, “I work for the same boss, the same project. The Master of the Universe is my boss. My project is the identity of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state, and making Israel more Jewish in a pluralistic and democratic and Jewish way.”

Calderon says that “I feel I am in some ways a translator” of traditional Jewish texts into the language of everyday life. She sees the Talmud as “living Torah, something that is “existential, a way to learn to know how to be a good person and mother, how to love and how to read.” In the Knesset, she believes her mission is “to study text and to use authority as a politician” to express the “beautiful values in the text like the sabbatical year”—the biblical injunction to return land to its original owners and forgive debts every seven years. She is now trying to translate the text about the sabbatical year into practical legislation that will take 10,000 families out of debt through a year-long process in which creditors, the government, and the families themselves will each pay a third of the money owed.

Throughout my visit, I’ve been amazed at the variety of ways traditional Jewish texts are being reinterpreted and remade by these teachers and institutions. The day before I leave, I meet with a currently-secular writer, who grew up in a religious home steeped in Jewish learning, at one of my favorite Jerusalem cafés. Like me, he occupies an in-between space, neither entirely secular nor religious; the fiction and poetry he writes is very much informed by values and texts from both the Jewish world and from international literary influences, some of which he has translated into Hebrew. He sees himself not as an Israeli writer but a Hebrew and Jewish writer. I am surprised when, like so many other Israelis, he does not ask me if I am secular or religious, but whether I’ve ever thought about living in Israel.

I tell him about the fascinating developments I’ve seen in my reporting on this trip, how there seem to be so many spaces for different approaches to Judaism: The Knesset with its Talmudically educated lawmakers and weekly Torah study classes, the Hebrew University Bible classroom, the television studios of Channel One, the mechinot programs around the country, the pluralistic study houses. None of this exists in the U.S. or anywhere outside of Israel. “I have thought about it,” I finally say. “I’m still thinking. And I like what I see.”

American Jews today tend to be most concerned with very basic issues—continuity, endurance, maintaining their longstanding institutions. Israeli Jews have different concerns. Beyond the existential issues of the country’s continued survival, the question of identity is of profound significance to the modern Jewish state. In the years ahead, the possibility of spaces where religious ideas are thought about and probed without obligations to a particular religious practice will become more and more crucial to Israel’s future as a Jewish and democratic state. And Israel’s struggle with the issue may ultimately help American Jewry find its own way to a new and more unified sense of Jewish identity and culture.

![]()

Banner Photo: Beth Kissileff / The Tower