Violent anti-Semitism has declined along with Russia’s once-huge Jewish population, but unpleasant jokes and stereotypes persist in popular discourse. At a time when Russia is again aligned with the mortal enemies of Israel, that is cause for concern.

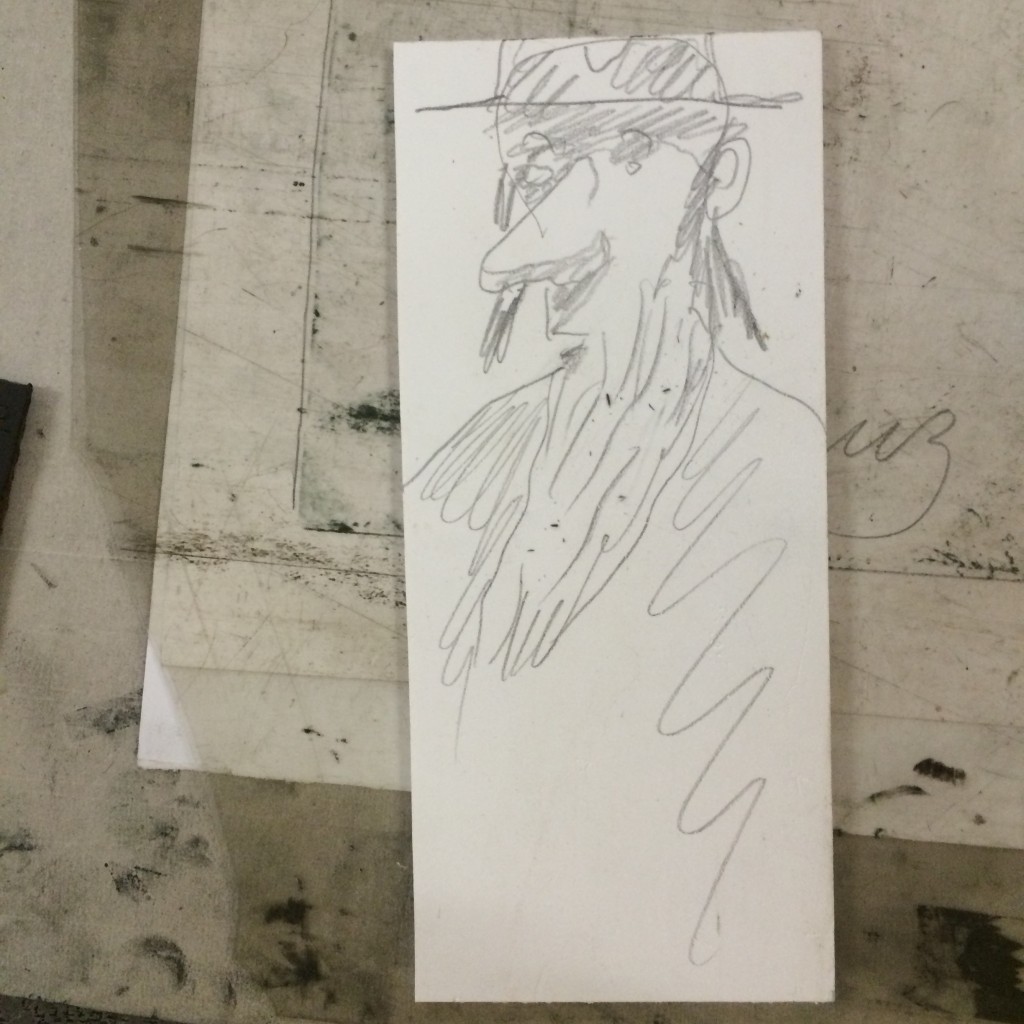

“So maybe I wish to draw a Jew.”

I stopped breathing for a second, chest tight, and looked around.

He began a simple sketch: A figure with a wide-brimmed black hat, beady eyes, unmistakable protruding nose, peyot. I scanned the room again. Everyone knew I was Jewish. One friend met my gaze and grimaced. Everyone else stared intently at the floor.

I was at a printmaking tutorial in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The artist, Oleg, was a character. His studio was cluttered with linoleum, cardboard, pencils, erasers, ink, paintbrushes, old t-shirts, books haphazardly stacked on top of each other and squeezed into every available crevice and corner. The studio felt comfortable. It smelled of linoleum and must. When we first arrived, Oleg sat us down on a circle of couches and offered us tea. A mug featuring the words “fuck die” surrounded by a heart stood prominently on a shelf. Oleg explained the printmaking process as he changed into a sweat-stained t-shirt covered with holes. At the conclusion of his lecture, he drew the stereotypical Jew as an example of how to produce a print.

He didn’t display any animosity toward Jews. He was just drawing a “Jew”; and this, he believed, is what a Jew looks like.

I did consider saying, “I am a Jew. Do I look like that?” But I didn’t. And it probably wouldn’t have mattered.

During my eight weeks in Russia on a program to study the Russian language, everyone I spoke to was quite candid about the popularity of Jewish stereotypes: Jews just want money, Jews are power hungry. Russians tell jokes about Jews all the time. Yet all claimed to have nothing against Jews and that the jokes were not anti-Semitic. They seemed to think there was little, if any, anti-Semitism in Russia.

Are they right? Is Russian anti-Semitism dead or mostly dead? It’s a difficult question. Most American Jews in Russia—myself included—aren’t sure. When we hear derogatory jokes about Jews or see caricatures of Jews with bulbous noses, we see anti-Semitism. But while I was in Russia, I was treated exactly like everyone else. When I cautiously told my Russian friends I was Jewish, none of them cared. They stayed friends with me. They treated me the same way they had before I revealed my closely guarded secret. And yet they openly admitted to telling jokes about Jews, and seemed to see nothing wrong with it. Like so much about Russia, attitudes toward Jews seemed to be a deep, impenetrable mystery.

Russia has, to say the least, a troubled history in regard to its Jewish population. As early as the 18th century, anti-Semitism was legally codified when Catherine the Great decreed that Russian Jews could live only in the Pale of Settlement, a far western region of the empire. After 1827, Jewish boys as young as 12 were conscripted into the Russian army for 25-year terms. Waves of brutal pogroms struck Russian Jewish communities during the 19th and early 20th centuries. In their aftermath, two million Jews fled Russia. During World War II, Stalin deported scores of Jews to Siberia, where many died. After the war, Stalin launched a campaign of anti-Semitism, ordering the murder of numerous Jews involved in the Communist party. His terrible purges continued until his death in 1953. By the late 1960s, many Soviet Jews were clamoring to immigrate to Israel. The Soviet Union refused to allow it. Only in the 1970s and ‘80s, after significant international pressure and condemnation, did the USSR begin to allow its Jews to emigrate. Even then, the greatest wave of Russian aliyah came only as the Soviet Union collapsed.

Out of a community that once numbered in the millions, there are now only about 186,000 Jews in Russia. Nonetheless, this constitutes the sixth-largest Jewish community in the world. According to the Anti-Defamation League, the level of anti-Semitism in Russia is roughly the same as the rest of Europe. Russians tend to be slightly more anti-Semitic than Western Europeans, but less anti-Semitic than much of Eastern Europe. Survey results that claim to represent the entire Russian population can be misleading, however. The fall of the Soviet Union, the re-embrace of Orthodox Christianity, and the rapid transition to capitalism and tenuous democracy brought sudden and jarring cultural changes to Russia. As a result, the attitudes of young Russians are often significantly different from those of Russians who grew up under Communism.

In fact, when I commented to one of my friends that anti-Semitism must be worse in smaller towns and among older people, her answer shocked me.

“Oh no,” she said, “I don’t think there’s much in smaller towns or among older people at all. I think the young people are more anti-Semitic.”

Unfortunately, the ADL’s statistics bear this out. The survey’s 2015 update found that anti-Semitic attitudes in Russia as a whole had fallen compared to 2014, from 30 percent to 23 percent. But anti-Semitism among those aged 18-34 remained static at 27 percent. In other words, young Russians are the most anti-Semitic.

Of course, the ADL survey only measures a certain kind of anti-Semitism. It tells you, for example, what percentage of a country’s population agrees with the statement “Jews have too much power in the business world.” It does not tell you what percentage wish their country was Jew-free, enjoys verbally assaulting Jews, or wants to blow up a synagogue.

Still, if anti-Semitism is indeed on the rise among young Russians—and it seems to be—it could become a much bigger and more dangerous phenomenon than it is today. As young people age and enter positions of power, anti-Semitism could rise to power with them. And as the less anti-Semitic older generation dies out, a larger and larger percentage of the population could come to hold anti-Semitic attitudes.

Yet my young friends didn’t consider anti-Semitism much of a problem. Ironically, it may be precisely because of the intensity of Russia’s historical anti-Semitism that this is the case. Russian-Jewish writer Isaac Babel’s account of a pogrom gives a picture of what Russian anti-Semitism used to be like. Babel wrote of a man with “gullet ripped out, his face hacked in two, and dark blood…clinging to his beard like a clump of lead.” He describes a “butchered old woman, a child with chopped-off fingers…the stench of blood, everything turned topsy-turvy, chaos, a mother over her butchered son,” the Jews “just lying there in their blood.”

Compared to that, an offhand joke about how the Jews are obsessed with money doesn’t seem so bad, especially when those who tell the jokes profess no anti-Semitic intentions. My friends all freely admitted to making such jokes on a regular basis. But none of them hated Jews or even disliked them. In the Russian mind, these jokes appear to be almost entirely disassociated from real-life Jews.

Studies show rising levels of anti-Semitism among young Russians—how alarmed should people be?

“We don’t really think of actual Jews when we make those jokes,” a friend of mine said. “They’re just jokes.”

“Like when Americans will say, ‘Oh, he totally gyped you out of your money’? And we don’t really think of actual gypsies when we say that stuff?” I asked.

“Yes, exactly.”

Nonetheless, the popularity of anti-Semitic jokes, as well as drawings, figurines, and paintings of stereotypical Jews, is worrisome. For the moment, Russian anti-Semitism is mostly latent. But one feels it could easily develop into something more sinister. The foundation has been laid. Russian President Vladimir Putin has increased diplomatic, economic, and military ties with Iran, and has stepped up his country’s military involvement in Syria. He has hinted that Israel’s air strikes against Iranian-backed Islamist groups in the Golan Heights might prove to be a sticking point. What if—despite Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s recently agreed-upon “mechanism” to prevent misunderstandings—Israeli and Russian military forces come into conflict in Syria? The situation could spiral out of control very quickly, and Russian Jews could find themselves blamed for Israel’s actions. Moreover, the Russian economy is struggling, and when the economy suffers, Jews tend to become scapegoats. The leap from racist jokes to racist violence is not as big as we’d like to think.

Despite all of this, violent anti-Semitism in Russia is now mostly confined to fringe skinheads and communists. Occasionally, violence does burst through the veneer of normalcy. In 2006, a neo-Nazi wounded nine worshippers at a Chabad house in Moscow. In 2008, a Holocaust memorial was defaced in Volgograd, a synagogue security guard was beaten up and prayer books destroyed in Nizhny Novgorod, and the blood libel circulated in Novosibirsk. Thus far, these have been isolated incidents. It remains to be seen whether they will remain so.

My parents were nervous when I decided to spend a summer in Russia. Part of this was due to their natural anxiety about sending a child half a world away. Part of it was due to the political situation. “I’m not about to join an opposition protest or anything,” I assured my mother. “I’ll be fine.” But part of it was due to their fear of anti-Semitism. That was a concern I didn’t brush off.

I am not a Hasidic Jew. I don’t take pains to dress modestly. I don’t cover my hair. I am a woman, so I don’t wear a kippah. If I didn’t tell anyone I was Jewish, no one would know. But my Jewishness is a strong part of my identity. I am very proud to be Jewish. I didn’t want to hide an important part of who I am for two months. I didn’t have Jewish friends or a Jewish community in Russia. My host mother, of course, did not prepare Shabbat dinners. So I would already be distanced from my Judaism. To pretend I wasn’t Jewish would be to completely, if temporarily, sever the connection to my heritage, religion, and culture.

My first night in Russia, I approached one of the program coordinators and asked, “Can I tell my host family I’m Jewish?”

He pursed his lips.

“Well, do you need to?” he replied. “It’s probably better to keep it to yourself.”

I decided to feel it out.

The first time I felt comfortable discussing the topic was with one of my Russian friends, a 20-year-old university student named Nastia. The program cautioned us not to discuss politics, even with Russian students assigned to help us as peer tutors. But we mostly disregarded this. Asking our friends’ opinions was not likely to become a problem. If they had different political views than ours, we simply didn’t argue with them. In fact, the Russian tutors were quite liberal, and their political views aligned closely with ours. They didn’t like Putin, were worried for their country’s future, realized their country was flooded with government propaganda, and sought out alternative news sources. This made me feel more secure about broaching difficult topics.

At one point, Nastia and I were walking down Nevsky Prospekt, the main street in Saint Petersburg. We were talking about something mundane—there were too many people, it was hot, that woman had beautiful shoes… My curiosity finally outweighed my anxiety, and I blurted out, “How do people feel about Jews here?”

Nastia shrugged.

“They’re fine,” she said. “We don’t really think about it. But we are fine with Jews.”

She nonchalantly mentioned the joking.

“Do you know anyone Jewish? Have you ever met a Jew?” I asked.

“Yes, I have a Jewish friend or two.”

“Ok. I just asked because я евреевская.” Because I am Jewish.

She reacted like I had told her the milk was on aisle seven or the light had turned green.

“Oh, okay.”

I considered whether I should press her on the jokes; explain that they were hurtful and ask her to think about not telling them. But I didn’t, just as I had not confronted the artist. I wasn’t sure what good it would do.

Despite the fact that I faced no outward discrimination, being a Jew in Saint Petersburg was alienating. I constantly scanned the crowds for kippot. Sometimes I mistook a baseball hat for one and got excited. At last, here was another one of us! Finally, I decided to attend Shabbat services. A quick internet search sent me to Saint Petersburg’s Grand Choral Synagogue—the second largest synagogue in Europe.

“Почему вы хочете проидти здесь?” asked the security guard outside the synagogue. Why do you want to enter here?

Unfortunately, I did not know how to say “Shabbat services” in Russian.

“Ummm, services…” I said desperately in English. He didn’t understand. I repeated myself and flailed my hands, gesturing at the synagogue. He still didn’t understand. I tried to mimic praying. “Бог, Бог,” I said. God, God.

“What is it you want?” he asked sharply in Russian. “Are you a tourist? You want to see inside?”

I responded in Russian, “Yes. Yes, I am a tourist. But I am also a Jew. I am here because I am a Jew.”

“Ahhhh, Shabbat services!” he said.

I nodded my head, relieved, and wondered about the chances of someone blowing up the synagogue. The guard’s suspicious eyes followed me as I walked across the courtyard and through the entrance.

The services were Orthodox, and I was not used to being in a separate women’s section. But as much as the gender segregation disoriented me, being among other Jews oriented me, giving me a sense of belonging and ease.

After services, I began talking to a Russian Jewish woman a little younger than me. I wanted to ask her everything about being Jewish in Russia. How did she grow up? Did she go to services every week? Did she, having attended Orthodox services, consider herself Orthodox? How did the different sects of Judaism work in Russia? And, of course, I wanted to know her perspective on anti-Semitism. Did it exist in Russia?

“No,” she said, “there is no problem here.”

“Really? Even the joking? Like, don’t people say ‘Oh, Jews rule the world,’ ‘Jews just care about money,’ and such?”

She brushed this off. Yeah, people said that stuff sometimes, but no one actually meant it.

“It used to be bad,” she said. “Now it is good. No one bothers me.”

Of course, those I spoke with about anti-Semitism do not constitute a representative sample of Russians. They tended to be young female students. They were friends. Our conversations about anti-Semitism were interspersed with talk about literature, boys, music, and TV shows. And yet, it is exactly the casual way their opinions were expressed that made them so valuable. I have no doubt that my friends were being completely candid. They were comfortable, at ease, interested in sharing their experiences and informing me as best they could about their culture. None of them were anti-Semitic, and none of them saw anti-Semitism around them.

But although they were honest, they were also far more liberal than the vast majority of Russians. It is quite possible that they simply did not run in anti-Semitic circles, knew little about anti-Semitism in general, and did not recognize it when they saw it.

All the same, being a Jew in Russia today does not seem much more dangerous than being any other sort of person in Russia. There are jokes. There are stereotypical caricatures and figurines of Jews. But while the popularity of these things is troubling, it does not speak to an immediate problem. There is the occasional violent incident—as there is in America and elsewhere. But Russian Jews do not feel afraid. They seem to be viewed more as curiosities than lesser beings. Ordinary Russians draw and paint and talk about Jews because they are interesting, distinctive, and different; not because they are inferior.

Nonetheless, there is some cause for worry. After all, isn’t this how it starts? First they are just different. Not worse, not better, just different. Then something happens, an economic downturn or natural disaster or political upheaval, and the different suddenly becomes frightening, even evil.

Anti-Semitism is bad and getting worse in Western Europe and many other parts of the world. Ironically, Russia, long a stronghold of anti-Semitism, has yet to be swept up in this wave of hatred. But it is not unthinkable that Russia’s long history of pogroms and purges will awaken once again, and the jokes and caricatures and stereotypes will come to be seen as the harbinger of something much darker and more dangerous.

![]()

Banner Photo: Miriam Pollock / The Tower