An emerging movement of ultra-Orthodox Jews seeks to break the cycle of pious poverty that grips their people and divides a country.

Some things are so universal that we tend to think of them as natural to every people and culture. People, no matter their origins, work to feed their families. From rural Siberia to the highest corporate tower in New York, we all go out and earn a living. However, there is one social group in Israel whose self-definition repudiates this apparent truth: the ultra-Orthodox. In their community, wage earners are often seen as second class, a tier below the permanent society of students. But this may be starting to change.

Israel’s ultra-Orthodox population, known as “Haredim” in Israel, is today at the center of an acrimonious debate within the country, which has grown so loud at times as to have displaced the conflict with the Palestinians at the center of Israel’s political discourse. For the most part, the Haredim do not serve in the army, despite Israel’s universal conscription, and they receive special tax breaks and have the lowest rate of workforce participation among Jewish Israelis, and the nation’s mostly secular, working, army-serving population has grown increasingly disgruntled.

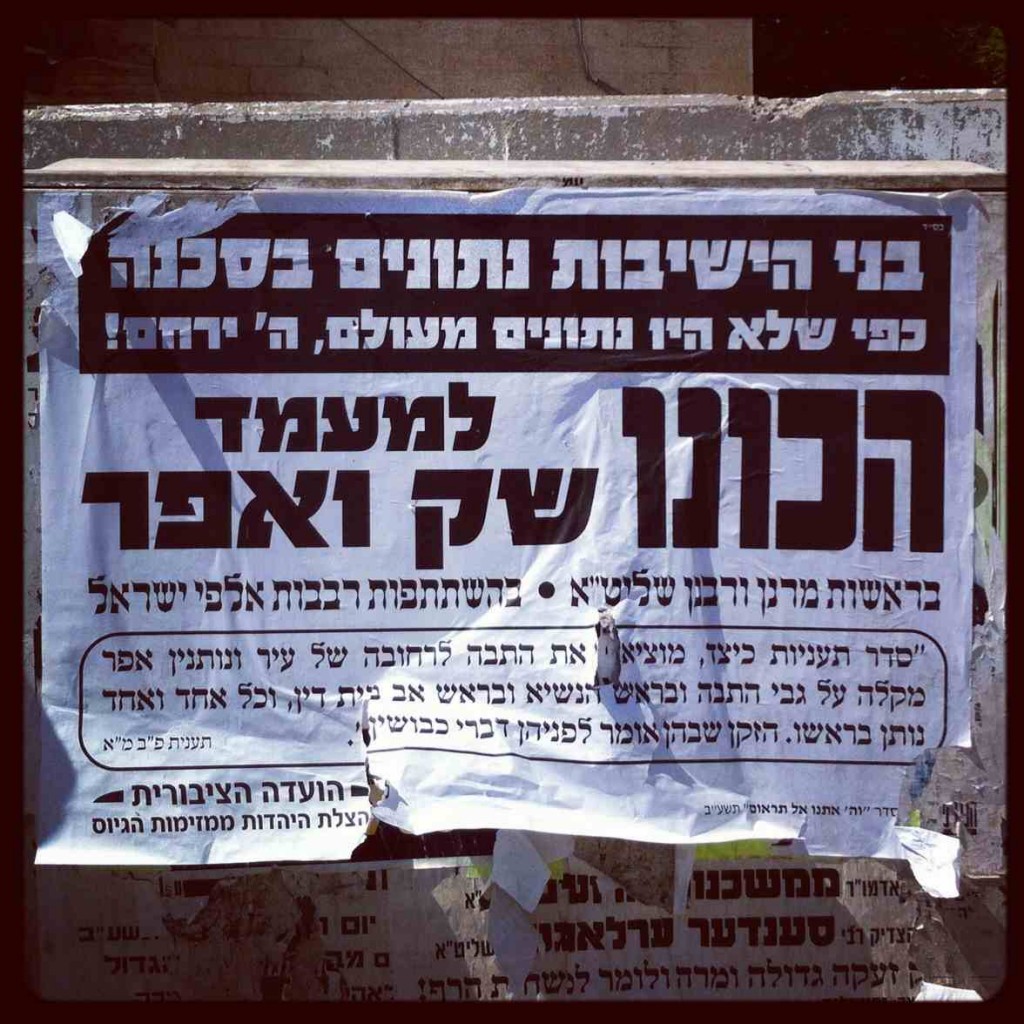

“Prepare your sackcloth and ashes.” Poster calling for protest against conscription.

Photo: Sam Sokol

However, what some have called a “silent revolution” seems to be taking place within this insular community. A somewhat amorphous group known as the Haredim Hahadashim, or ‘New Haredim,’ has emerged as something of a political force in Israel. These New Haredim differ from traditional Orthodox in ways that stand to transform not just their own community, but Israel’s political and social landscape—if their ideas and way of life take hold.

By some estimates, including data extrapolated from voting records, up to 10 percent of Israel’s ultra-Orthodox may be considered New Haredim, and another 10 percent may be silently sympathetic despite the intense social pressure to shun their ideas. During the recent Israeli Knesset elections, both dominant Haredi political parties, Shas and United Torah Judaism, vied to gain the support of a small political party called Tov, which represents the New Haredim, who researchers say constitute a phenomenon never before seen among Israel’s ultra-Orthodox: A middle class.

But the emergence of the New Haredim is clearly perceived as a threat by the existing ultra-Orthodox power structures. The newspaper Yated Nee’man, widely considered the mouthpiece for the leadership of the “Lithuanian” stream of ultra-Orthodoxy, has condemned them vigorously and loudly, proclaiming them a threat to the religious status quo. In a recent editorial, the paper railed against against the New Haredim, explaining that “It is clear that working for one’s livelihood does not disqualify a person as a ‘Hareidi.’ To a true Haredi, his career is no source of pride for him. If circumstances force him to leave the study hall and seek a livelihood, he will do so against his will and not proudly declare that he is ‘a working Hareidi.’”

The term “Haredi” comes from the Hebrew word for trembling or, depending on context, anxiety. Like the American Shakers and Quakers, it is a direct reference to the fear of God, or of transgressing His laws, that lies at the core of the lives of adherents. Though the ultra-Orthodox community, which now numbers around 700,000 out of the country’s six million or so Jews, is far from a majority, fully one-third of Israeli kindergartners attended Haredi schools as of 2009, according to the Israeli Education Ministry. And that number has risen rapidly, growing 26 percent between 2001 and 2009 and reflecting a massive surge unparalleled in Israeli society.

The vast majority of Haredi students receive not even a basic secular education, however, missing out on the core curriculum that is standard in Israel’s non-religious and religious-Zionist schools. As the Haredi population increases, many experts warn that unless they begin to integrate secular studies into their schools, the economic consequences of a large and growing demographic that not only does not work but depends on state welfare to support their families—the average Haredi family has around seven children—could be dire.

Thousands of Haredim rally in Jerusalem against drafting Yeshiva students, June 2012.

Photo: Yonatan Sindel/Flash90

But the New Haredim represent a divergent path—and possibly a way forward for the larger community. Rabbi Dov Lipman, an American Haredi immigrant from Silver Spring, Maryland, was recently elected to the Knesset on the Yesh Atid party list, a faction aimed at “equalizing the burden” of military service and economic contributions.

Lipman, who was elected to the Knesset on the strength of his anti-violence and diversity work, is a good example of the American model of ultra-Orthodoxy, which despite being part of the Lithuanian stream, generally allows and even encourages its members to clock in for work. Many of the American Haredim hold down white collar jobs and have college degrees. Lipman, the son of a judge, himself spent years in yeshiva earning his ordination, but also fully engaged with American culture and academia, earning a master’s degree in education from Johns Hopkins University.

In an op-ed he wrote last year, Lipman called on the government to allow the ultra-Orthodox into the workforce. To outside ears, it might sound like a strange thing to call for, since the mainstream of Israeli society has vehemently expressed demands that the Haredim share in bearing the national burden. But because citizens who don’t serve in the army are often barred from entering the job market, and the result has often been that Haredim who don’t serve when they are in their late teens end up unable to work even if they want to.

Israel’s ultra-Orthodox culture is in many ways fundamentally different from that of their co-religionists in the diaspora. Although much of the same worldview is common to both American, European and Israeli Haredim Israel’s ultra-Orthodox community has its roots in the poverty-stricken, pre-state settlement of Palestine, known colloquially as the Yishuv. The Jews of the Yishuv mainly subsisted off of charitable donations sent by religious Jews living abroad who believed that a core group of Jews dedicated to studying Torah must live in Israel. While the Jews of Poland, Lithuania and Russia worked for a living, these same communities who sent their hard-earned zlotys and roubles to the holy land believed that the religious Jews of Palestine neither could nor should support themselves in the same way. Studying Torah full-time was inherent to the local religious culture—even if it was not part of traditional Jewish culture anywhere else.

After the Holocaust, the leader of Israeli ultra-Orthodoxy, Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz, also known as the Hazon Ish, made a famous bargain with then-Prime Minister David Ben Gurion to obtain exemptions from army service for several hundred ultra-Orthodox youths, in an attempt to salvage a tradition of learning he felt was in danger of extinction. As the ultra-Orthodox community began to grow in numbers and financial security, the number of exemptions grew, and with it the expectation of lifelong study. When the Haredi political parties began to gain strength in the Knesset as a “natural” partner of the newly triumphant nationalist Likud party in the late 1970s, change started to rapidly affect the community.

Rabbi Natan Slifkin, a self-declared “post-Haredi” Jew, Orthodox Rabbi, and author notes in his monograph, The Making of Haredim, that:

The ultimate step in the evolution of the kollel [religious school for married men], which spread in the latter part of the twentieth century, was its presentation as an expectation of every young man in the Haredi community. In more moderate Haredi circles in the United States, this is only expected for a year or two following marriage, while in the rest of Haredi society in the U.S. and Israel it is expected to continue for at least a decade or two, if not indefinitely.

But it wasn’t always like this. “Up until 1977 the percentage of Haredim who went to work was in the 80 percent range and in 1977 they joined their first government, the Menachem Begin government, and all of a sudden they started getting all these funds,” Lipman says. “You call the Haredim who work the new Haredim but I call them to old Haredim. The extremists are the new ones.” In 2011, the percentage of Haredim with regular jobs was under 50 percent, according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics.

According to Lipman, “everybody understands that there is a need for yeshivot and kollels but the terminology that they are using in the Knesset chamber itself indicates a self-serving and almost hateful perspective.” In his eyes, the ultra-Orthodox politicians “never really, truly represented the interests of the broader Haredi population.”

But over the past decade, several significant changes have occurred, presaging the emergence of Tov almost four years ago. The first and arguably most significant is the emergence of the “Nahal Haredi”—or IDF battalion for Haredi soldiers formed in the late 1990s which provides a strictly kosher, gender-segregated environment for yeshiva students to serve. Though it was not accepted socially among Haredim as it is in secular society, the sight of ultra-Orthodox youth in uniform was suddenly no longer quite as unthinkable as it had been.

It wasn’t long after when a number of ultra-Orthodox academic colleges opened up to provide an ultra-religious environment for those wishing to train for a profession. In parallel, companies like Modi’in-based hi-tech company Matrix have created programs to employ Haredi women who want to support their husbands in kollel. (There is now even a Haredi High Tech Forum.)

As more and more Haredim women begin to work and mingle with their secular counterparts, many believe that attitudes will begin changing within the insular “black hat” community. In a recent paper, Israel Democracy Institute researcher Haim Zicherman wrote that, “over the last decade in Israel, cultural and economic developments and changes in leadership have been weakening the ‘society of learners’—in which ultra-Orthodox Jews devote themselves to full-time study rather than joining the workforce—and strengthening the individual Haredi. At the same time, however, a significant sub-group has begun to emerge: a Haredi middle class.”

“I think that the numbers are less important than the movement,” Zicherman says. “I attempted to do a simulation based on the group of Tov supporters. If you take Tov in Beitar, where they had one of nine, this says that it is more than ten percent. In Bet Shemesh, I think, they have seven percent.”

In the Haredi community, both ideology and identity are heavily informed by the concept of daas torah, or the Wisdom of Torah. According to this doctrine, the rabbinic leaders, especially the deans of the largest yeshivas, possess an almost mystical understanding of truth—even in areas in which they are admittedly not experts—by dint of their years of study. If one wants to remain true to the faith and a part of the community, one must follow their rulings in all matters.

However, the New Haredim continue to consider themselves Haredi, say experts like Zicherman, even if they are acting in contradiction to the dictates of their nominal rabbinic leaders. Many believe that they are being loyal to the Haredi ideal as it was before the rise of the mass kollel system.

Zicherman says that the rise of the Tov party, which fielded candidates for the first time in elections for city council in Bet Shemesh and Beitar, indicates that the New Haredim are a significant force, even as he admits that it’s hard to quantify their real numbers.

Tov has thus far refrained from taking part in national elections and is virtually unknown outside of the Haredi community, but its leaders have said that they are considering running in the elections for the 20th Knesset, showing that, in their minds at least, they have a chance to make the minimum election threshold, a sign that they are increasingly confident and believe that they are growing in numbers.

Extrapolating from election results from Bet Shemesh and Beitar, Zicherman and his research partner, Lee Cahaner of Oranim College, claim that there are thousands of these new Haredim, with one-fifth of Beitar residents backing the party in its first political foray and 10 percent of Bet Shemesh Haredim supporting the party.

Tov party spokesman Yitzchak Horovitz agrees with Zicherman’s evaluation of his party’s strength, and through it, the strength of the new Haredi community. “We carried out a survey a few months ago to check how much of the populace supports our ideas and it was about 20 percent of the Haredi population,” he says. “But out of that twenty percent,” he says, “only half are actually willing to go out and vote for Tov.”

Though he is ostensibly one of the faces of the New Haredim, Horovitz says he does not like the term, preferring “working Haredim.” But whatever the nomenclature, Horovitz insists that Tov is a growing movement. “There are more studying in academic institutions, more people going out to work and more people finding that they cannot sustain the [economic status quo].”

In this Horovitz is undoubtedly correct: On the one hand, the community is one of the poorest in Israel, while on the other, secular Israelis incensed over serving in the IDF and paying taxes to defend and support the ultra-Orthodox recently formed a governing Knesset coalition that, for the first time in years, has excluded Haredi parties, with the explicit aim of “equalizing the burden.” Both economically and politically, the status quo is unsustainable.

“The Haredi middle class is 13 percent [of all Haredim according to the bank of Israel,” researcher Lee Cahaner says. Whether that is a significant change, however, was not something she felt ready to comment on. “I really don’t know,” she said, explaining that most of what is known about this group is based on extrapolations and guesses. The New Haredim “will be growing” in the future and it is a “phenomenon” even if it can’t be precisely quantified, she added.

Habituation is a powerful force, Cahaner added. Once you have started voting for one party, it becomes almost automatic. Cahaner says that the Haredi reaction to Tov is significant because it shows that there are many who want to “go after this way” but are still afraid to do so. Change is on the way, but it may not come fast.

Dov Lipman believes that the core problem among the ultra-Orthodox is the concept of daas torah, the ruling dogma of the ultra-Orthodox. According to Lipman, mpst Haredim will privately admit that working is the way to go. Though it may seem overly optimistic, there is no question that many who would otherwise want to work or serve are deterred by the social stigma of not being part of the elite “community of learners.” One ultra-Orthodox Sephardi shopkeeper put it best when he said, “I cry every time I vote for Shas. But what can I do, [former Chief Rabbi] Ovadia Yosef says we must.”

But despite severe censure from leading rabbis, the New Haredim are not deterred. They have been humiliated by schools not admitting their children, and potential marriage matches for their older kids that have soured because of their views. Yet they have stood firm and begun choosing their own, more accommodating rabbis.

Horovitz acknowledged this fact, saying that many synagogue rabbis have begun to support his movement, even as the influential yeshiva deans oppose it. However, he says that a return to the roots of orthodoxy, with adherents both working and learning, is necessary. After all, he asserts, the Talmud itself says that any Torah study unaccompanied by work will lead to sin.

But there is skepticism that any real change is occurring on the ground. Dan Ben-David, executive director of the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel, believes that while the anecdotal evidence supports the notion of a New Haredi, the economic measures for such growth are unclear. Moreover, he and other experts believe that the internal changes coming from the Haredi sector, while laudable, are not coming fast enough to stave of long-term economic disaster without government action:

There is apparently a rising interest among Haredim in [academic] programs but the bottom line is that it’s like a rearguard action. As long as the children don’t start receiving a basic education, we are going to have to continue paying a huge premium on doing this in a sort of back-door way, not to mention the high cost because of the inefficiency involved.

But like Zicherman and Cahaner, Ben-David says that there is “quite a bit of anecdotal evidence of a regime change, especially among the younger Haredim who appear to recognize the need to have to go to work and the inability of the country to support lifestyles of non-work at the rates that we’ve been accustomed to in the past.”

While Haredi magazines like Mishpaha [“Family”] argue that there is no need for government intervention as change is coming as fast as it should be, many academics and politicians disagree. Corrine Sauer of the Jerusalem Institute for Market Studies, a think tank that specializes in studying social progress in Israel, notes that change cannot come while Israeli tax law remains written in such a way as to provide certain sectors financial incentive to refrain from seeking employment.

Politicians like Lipman have begun to push for changes in policy and law that would provide expanded incentives and opportunities for Haredim to join the workforce. Together with Labor Party legislator Erel Margalit, Lipman has established a Knesset committee dedicated to focusing on Haredi integration into the workforce and, if he is to be believed, there is a growing groundswell of silent support for his efforts.

Between the New Haredim and outside pressure, change may come.

***

Editor’s Note: This is an updated version of this essay. To see the original version, click here.

Banner Photo: Uri Lenz/Flash90

![]()