After so many rounds of failed talks leading to horrid violence, isn’t it time to change the approach?

I returned from Israel the same day the Israelis launched Operation Protective Edge. I do not know precisely when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu issued the order, but it must have come in the early hours of Tuesday, July 8. My El Al plane took off at 1 AM the same day.

I had arrived in Israel on June 30, obviously absent any premonition of what was to follow. While I was there, the news broke that three kidnapped Israeli teens had been murdered. The recording of their final call to the police was released. The kidnapping and killing of Mohammed Abu Khdair and the subsequent investigation, arrest, and confession of the Jews responsible for it occurred. Rioting exploded in Israeli-Arab communities. The beating of Palestinian-American teenager Tariq Abu Khdeir took place. More Israeli-Arab rioting. The massing of IDF troops and materiel near Gaza. The call up of 1,500 reservists. And then, within an hour or two of my flight back to Washington, Netanyahu gave the green light. All the while, rockets from Gaza rained down on Israeli civilian populations with increasing ferocity, deeper and deeper into Israel.

It was quite a week to digest, and subsequent events have made my time in Israel feel tame. In this article, I hope to use this trip in order to explain that, while the series of events I witnessed and events transpiring right now could become the beginning of a third intifada, focusing on such a concept distracts from the reasons why the conflict is boiling over yet again.

The main reason is extreme popular frustration over the fact that Israeli, Palestinian, and especially foreign leaders have falsely led their people to believe that politics can settle the conflict.

The two intifadas were emotional reactions to longstanding grievances sparked by single events that personalized those grievances. Because they were reactive and based on already existing grievances, they were by definition an effect rather than a cause. Yet when political leaders look at both crisis management and solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, they have taken these grievances and turned them into causes. They have done so by making them the issues over which Israelis and Palestinians are supposed to negotiate compromises in order to achieve peace.

But what if this is fundamentally mistaken? What if violent emotional outbursts like the intifadas and what we’ve seen this summer occur not because grievances go unaddressed, but because leaders have built the expectation that a political process is the way to peace, and have not been able to fulfill this expectation? After all, from Camp David in 2000 to today, the most extreme outbursts of violence have come directly after each failure of the peace process.

Although the second intifada was raging during the first four years of President George W. Bush’s presidency, it started during President Bill Clinton’s second term, following the failure of Clinton’s push for peace at Camp David 2000. Compared to Clinton and current President Barack Obama, Bush took a relatively hands-off approach to the peace process. Nonetheless, he did undertake a peace initiative in the last year of his presidency, and the 2008-2009 Israel-Hamas war came as that process was petering out. Moreover, despite rigorously engaging in attempts to solve the conflict, Obama’s first five years have already seen two wars, with the current one being the most intense since Hamas took over Gaza in 2006.

If we do not understand the connection between violence and the unrealized expectations of the political process, we will continue to misdirect ourselves. If this happens, the reaction from the Israeli and Palestinian governments, as well as the international community, to this conflict will be as it has always been, and will produce more violence yet again.

Palestinian intifadas are sparked, whether spontaneously (1987) or planned (2000), by events. In 1987, a car accident in Gaza sparked the first intifada when false rumors spread that the four Palestinians killed were deliberately hit. Ariel Sharon’s televised visit to the Temple Mount in 2000 sparked the second, though we now know that Yasser Arafat used the visit to ignite the gunpowder he had previously spread as a backup plan to distract his constituents from his political failure. A casus belli suggested for a third intifada is the killing of Mohammed Abu Khdair, which sparked massive rioting and non-lethal violence. We must remember, however, that there is a vast and murky space between calm and intifada. We cannot call this an intifada yet.

The events that marked my visit to Israel were not all conflict-related. But the kidnapping and murder of the three Israeli teens had conflict written all over it: The boys were religious Jews traveling to Jerusalem from a yeshiva in Gush Etzion, a bloc of communities commonly referred to as settlements. The perpetrators were Palestinians who are not only from Hebron—on and off the most confrontational city in the West Bank—but had ties to Hamas and could reasonably be called a Hamas cell (in fact, according to court documents, the ringleader has confessed that Hamas funded the attack). The incident generated a symbol in which Palestinians and their supporters raised three fingers to proudly claim the event as one relevant to their cause.

Israel’s response was an attempt to root out Hamas across the West Bank with support from Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, who condemned the kidnapping and defended his decision to order his Preventative Security Forces (PSF) to cooperate with Israel. As Ramadan began and Israel continued its operations against Hamas, rockets rained down on Israel from Gaza in numbers that increased first by the day and then by the hour. Twenty-eight days after the kidnappings, a storm has broken over Gaza and southern Israel. The spread of anger, tension, and violence from one Palestinian territory to the other is a quintessential symbol of the conflict.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, Israeli Justice Minister Tzipi Livni, and Palestinian Chief Negotiator Saeb Erekat address reporters on the Middle East Peace Process Talks at the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C., on July 30, 2013. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

Also swept up in the storm was the kidnapping and killing of one Palestinian boy, the beating of another, and the subsequent rioting. Although the kidnapping and killing of the Palestinian boy was retribution for the kidnapping and killing of the three Israeli boys, and the Palestinian-American boy was beaten at a riot sparked by the arrest of the Jewish extremists who confessed to the crime, there was also an intra-Israeli dynamic very much at play. Most of the riots occurred in Arab towns in Israel, many of them far from the Jerusalem area where the crimes occurred. Radical Islam funded by Arab states like Qatar is gaining traction there because it is providing services and a sense of belonging that many Israeli-Arabs have trouble finding elsewhere. These dynamics have little to do with the conflict, and must be understood as a separate issue that Israel must address.

Nonetheless, there are strong reasons for worrying that a third intifada could be on its way. Fortunately, Mahmoud Abbas is not Yasser Arafat when it comes to the use of violence. Arafat publicly and privately promoted violence against Israel for the vast majority of his rule, while Abbas is unabashedly against violence both publicly and privately. He has gone so far as to task the PSF with assisting the Israeli Defense Forces in their West Bank operations and defending that decision to Arab foreign ministers in Saudi Arabia.

Unfortunately, today’s Palestinian youth are not the youth of 2000; they face challenges in participating in Israeli commerce and the labor market stemming from Israel’s reaction to the intifada. It took dozens of despicable acts of violence and terror spanning two intifadas for Israel to begin erecting security measures to protect its people. Few remember today that, prior to 2000, Israel and the West Bank were effectively one homogeneous and borderless territory. The economic cost to the Palestinians of these security measures during “peacetime,” if it can be called that, has been significant.

Those who were of working age during the intifadas, especially the second one, learned hard lessons about the cost of their violent uprising. In the first year of the second intifada, half of the Palestinians who worked in Israel lost their jobs because they were unable to commute to their workplaces. At the same time, employment, private investment, and government revenues in the West Bank declined significantly. Over the course of the entire second intifada, Palestinian employment in Israel declined by 60 percent. While statistics are spotty, it is fair to say that the labor market and many other sectors of the West Bank economy have barely recovered.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas approach a gaggle of reporters after concluding their meeting in Ramallah, West Bank, on June 30, 2013. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

This is well understood by many Palestinians who know what it was like before 2000. To them, conflict means a decline in economic opportunity and their standard of living. But the Palestinians rioting today are not those who experienced the intifadas and lost their economic livelihood as a result. They only know the security barrier and the IDF’s presence near their cities, as well as the vitriolic propaganda spread by Hamas, Fatah, and others. They do not have the benefit of experience in the way their elders do. As a result, they are less inclined to understand what they have to lose by resorting to violence, including things as fundamental as the ability to have and support a family.

Given the raging Israel-Hamas war and the possibility of a third intifada, the international response has been as predictable as it is misguided. While the human cost of the war and the intensity of the rioting ratchet up, so do the efforts of world leaders and bodies to stop the violence immediately, convince the sides to agree to a ceasefire, and work out the issues through political dialogue. The alternative, which would be to let the war play out and let Israel and the Palestinian Authority deal with the riots, is so unbearable to a critical mass of outside observers and foreign leaders that it most likely will not be allowed to happen. Before either the war or the riots can be brought to a natural halt, international pressure will force them to end, albeit temporarily, and the foundation of a political process will slowly begin to be erected again.

Israelis and Palestinians know how this process works all too well. They have lived through it again and again, and each iteration has resulted in broken expectations and disillusionment. Israelis and, in particular, Palestinians have reached this juncture of absolute frustration because it comes just after one of the most obvious broken expectations in recent years: The failure of the so-called “Kerry Initiative.”

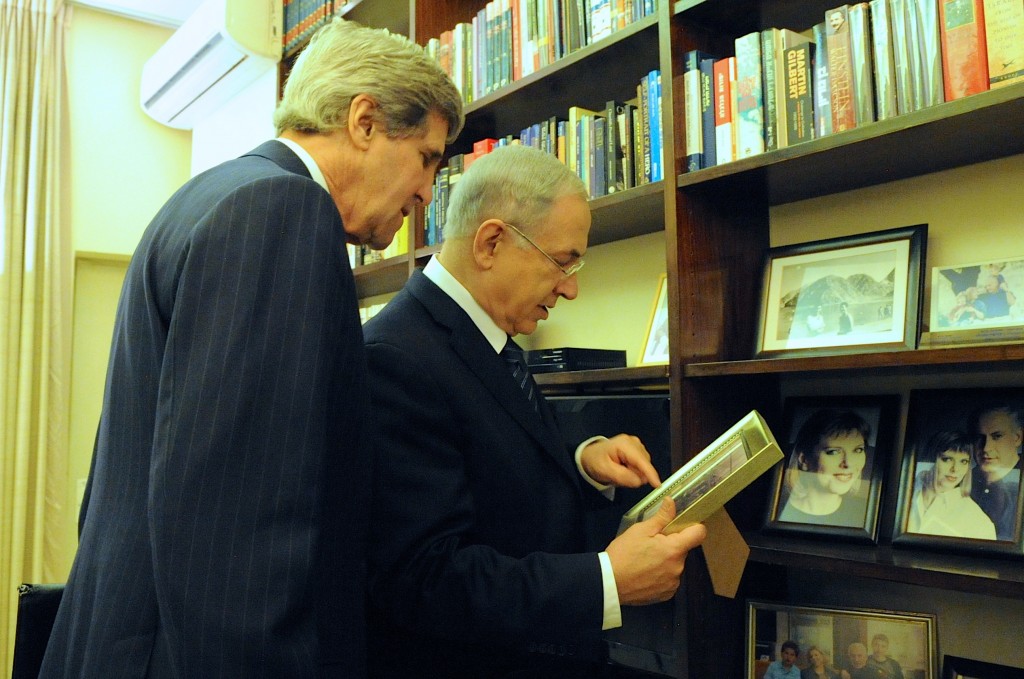

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu settle into their seats in Netanyahu’s private office before a one-one-one discussion in Jerusalem on January 2, 2014. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

To understand this, one must understand the nature of the broader expectations created by Israeli and Palestinian leaders. The first is the most symbolic: The two-state solution. Despite repeated declarations of commitment to the two-state solution over many years, there is a high level of skepticism among Israelis and Palestinians that the other side means what it says. There is also great skepticism that their own leaders actually want a two-state solution.

Fueling this disbelief is ample evidence, mainly rhetoric and actions that make a two-state solution more difficult to achieve. Palestinians see the expansion of settlement blocs around Jerusalem as evidence that Israel will not make territorial concessions; while Israelis see public and financial support for Palestinian terrorism and incitement as proof that the Palestinians do not accept Israel’s existence. Based on what I saw and heard during my trip, the expectation of a two-state solution has been replaced on both sides by the expectation that a two-state solution is impossible to achieve for the foreseeable future, and thus a future without peace is inevitable.

Another broken expectation is that of a West Bank economic revival and subsequent political dividend. Mahmoud Abbas’ precarious standing as president of the Palestinian Authority drives him to eliminate all potential political rivals; and the father of the West Bank’s economic revival, Salam Fayyad, was very much a potential rival. Buoyed by Israeli, American, and European support, indicators like gross domestic product and trade had been moving in a positive direction under Fayyad, but have slowed since his expulsion from the Palestinian Authority leadership. Palestinians had long been unhappy with their economic status, but the idea that improving their economy and quality of life would improve the situation between them and the Israelis did not come from them. It was sold to them by their political leaders. The breaking of this expectation not only meant a lack of economic improvement for the Palestinians, but also a lack of the promised improvements in Palestinian governance and a reduction in tensions with Israel.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas welcomes U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry for a meeting focused on final status negotiations with Israel in London, United Kingdom on September 8, 2013. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

Another powerful broken expectation among the Palestinians is that they can have their proverbial cake and eat it too. What this means is that, due to anxieties about his political, if not personal, survival, Abbas has made promises to his people that contradict the promises he makes to foreign mediators. Inasmuch as one believes in Abbas’ commitment to the two-state solution, it would be naïve to believe that he will sacrifice his life or even his position by betraying a promise he has made to his constituents, even if he has made the opposite promise to Israel or a foreign mediator. Take, for example, his commitment to securing the return to modern Israel of every last Palestinian refugee.

Abbas’ constituents are not naïve. They know the game Abbas is playing; even though many loathe it and cannot decide which Abbas is lying, a topic of great debate in Palestinian society. Even as support for a two-state solution, and even for negotiations themselves, is declining as the post-intifada generation grows into adulthood and positions of influence, Abbas has led the aging mainstream Palestinian population with doublespeak. This is being met with less and less tolerance among the young, who have little faith in the expectation that the Palestinians will achieve their goals by playing the political game with the Americans, Europeans, and Israelis.

A broken expectation on the Israeli side is that the Palestinians can be kept at bay with superior security operations and defense technology. Such superiority squashed the second intifada, so it was believed that more of the same would fend off a third. In the absence of a third intifada, the Israeli government has yet to fully appreciate the impact of its asymmetric military power on the tolerance and support it receives internationally and especially from the press. Moreover, Hamas’ new rocket capabilities and infrastructure are proving that even the most advanced missile defense system in the world neither prevents nor stops attacks, and does not eliminate the need for using ground troops. Iron Dome went from a game-changer in 2012 to an intermediate step toward a more advanced defense system in 2014.

On their own, however, domestically-created expectations would not have been enough to inspire this summer’s outburst. International participants have played their role as well, and it is outsized.

There is a long history of such interference. During the British Mandate period, the English told both sides that they would get what they wanted. A series of important decisions, from the Balfour Declaration of 1917 to the Churchill White Paper of 1922, showed significant changes in policy over who was going to get what lands and what rights. The first High Commissioner of the British civilian administration frustrated the Arabs through actions they viewed as pro-Jewish. In order to satiate the Arabs, he eventually gave the position of Grand Mufti to a popular figure known for his anti-Semitism and belief in the use of violence against Jews. The Mufti ushered in an era of increased violence between Arabs and Jews that lasted throughout the remainder of the British Mandate, which ended without the setting of borders and all but guaranteed further violence.

Since the Arab and Muslim states chose not to accept the United Nations’ partition plan and Israel declared its independence, many countries have tried to solve the conflict by supporting and participating in multilateral efforts. They did so because they felt they had an interest in a resolution and the leverage to achieve it. Many Arab and Muslim states have been involved, including Egypt, Jordan, and Turkey, with the Saudis and Qataris playing a special role in Arab League efforts.

Opposition to Israel among Arab and Muslim states has persisted since 1948, but as the region has become more complicated, some like Saudi Arabia and Turkey have found it in their interest to have relations, albeit secret and limited, with Israel. Yet these pragmatic relationships have not swayed Saudi or Turkish public rhetoric toward Israel or their perspective on the Palestinian cause, which they support quite rigorously; if for no other reason than to distract their domestic and international constituencies from their own shortcomings. Despite appreciating Israel’s role in the region, they still feel it is in their best interests to feed unrealistic Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim expectations that Israel will be made to pay a steep price for its existence and actions.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shows U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry a photo of him as a young soldier during a tour of his government residence in Jerusalem that preceded a dinner meeting focused on Middle East peace on January 4, 2014. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

Between 1948 and 1973, some backed up their rhetoric with force. Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Jordan attacked Israel multiple times until, finally, Israel broke their collective pan-Arab back. Since 1979, Iran has made destroying Israel one of its chief foreign policy goals. As a result, it supports proxies like Hamas, Hezbollah, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and builds a nuclear weapons program in order to amplify their investment in these groups and directly threaten Israel with the ultimate weapon.

For Israel, the cost of these efforts has indeed been high in blood and treasure. As a result, the impact of the expectation that Israel will be destroyed has been palpable, and manifests itself in the belief among Palestinians that intransigence in negotiations buys them and their better armed and funded supporters more time to destroy Israel.

Yet over time this expectation has eroded as leaders in Arab and Muslim states devote less time and attention to the Palestinians, making the Palestinians feel more isolated and insecure. Egypt and Jordan now have peace treaties and normalized relations with the Jewish state, and cooperate in ways that stifle the Palestinian effort to terrorize and destroy Israel. Syria, despite Bashar al-Assad’s rhetoric, has worked hard to maintain its ceasefire with the Jewish state. The Gulf states, except for Qatar, devote less and less time to the Palestinian cause. And Iran’s support is stretched thin due to its efforts in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon. All of this has broken the Palestinians’ expectation of brotherly Arab and Muslim support, but not their need for it.

Europe has played various roles, with the British, Germans, and French making the most significant efforts. Canada has played a unique part, with the majority of its efforts focused on security issues such as peacekeeping and PSF training. Russia has been a major player as well.

All of these countries have been motivated by the conviction that a two-state solution is needed. And they have generated their own expectation that international involvement in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will improve the situation. We now hear constant cries for international mediation regardless of whether it is requested.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry settle into their seats in the courtyard of the Prime Minister’s Residence in Jerusalem before a dinner meeting focused on Middle East peace on January 4, 2014. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

America’s role has been especially damaging in this regard. Every major effort to end the conflict, from the first Camp David summit to the Oslo Accords, has been led by an America convinced that the two sides need a neutral broker who can guarantee the material and financial components of an agreement. This conviction was often forced on Israelis and Palestinians regardless of how either side felt.

Because the U.S. often faced opposition to its efforts from both the Israelis and the Palestinians, America had to incentivize both sides to participate. And with each new incentive, like a settlement freeze or acceptance of the 1967 lines or Palestinian recognition of Israel’s Jewish identity, the minimum requirement for negotiations has risen, building upon the expectation that the U.S. could deliver not only formerly established minimum requirements, but new and loftier ones as well. By continuing to play this game, the U.S. has fed expectations that by 2014 it is clearly unable to meet.

The most damaging of these U.S.-driven expectations is that the two sides can be partners in peace. Ehud Barak’s two-state solution offer to Yasser Arafat in 2000 is widely recognized as being one of, if not the most, concessionary offers Israel has made amidst a dearth of Palestinian offers. If successful, the deal could well have cost Barak his political career. The whole thing was chaperoned and championed by President Bill Clinton. That Arafat turned down this offer and gave the green light to start the second intifada established a space in popular Israeli discourse that believes the Palestinians will never accept coexistence.

While George W. Bush’s last-minute effort in 2008 led nowhere politically, expectations on all sides were non-existent. What was very surprising, then, was the secret offer Ehud Olmert made to Mahmoud Abbas that, if speculation is to believed, was every bit as generous as Barak’s 2000 offer. The offer was made without coordination with the U.S., so it is hard to give the Bush Administration, which had never promoted such generous Israeli concessions, much, if any, credit for it. And again, the Palestinians turned it down with only the 2008-2009 war as a counter-offer, reinforcing the perception that the Palestinians do not want peace.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry has a private chat with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas before a meeting in Ramallah, West Bank, on December 12, 2013. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

President Barack Obama’s efforts have been no less destructive, and have made matters worse by creating a new Palestinian expectation: That they will not have to participate in negotiations without prior Israeli concessions. The settlement freeze during Obama’s first term, his support for the 1967 lines, and his prisoner release prizes to the Palestinians for talking to Israel all backfired: They became the Palestinians’ minimum requirements, which raised the cost for Israel while lowering the cost for the Palestinians.

Abbas took full advantage by accepting concessions without giving any of his own. Obama’s expectation, which Israelis were once again pressured into accepting, was that if Israel gave something, the Palestinians would too. It didn’t happen. During his first term, Obama secured a 10-month freeze on settlement building. This became the carrot that drew Abbas into negotiations. But Abbas negotiated little, late and in bad faith, during this period, while Israel saw no reward for agreeing to the politically costly freeze.

In the spring of 2011, as revolution was spreading across the Arab world, Obama thought he could capitalize on frustration over poor governance by reviving the peace process, even though the Palestinian territories and Israel were two of the calmest places in the region. He announced his intention publicly with a speech in which he declared that the prevailing borders of a two-state solution should be based on the pre-1967 lines (with “land swaps”), a first for an American president. Israel had always opposed this border formula out of security concerns. The Palestinians had not put the emphasis on this new precondition in quite some time, and had already negotiated without it. Obama unilaterally raised the bar to one the Palestinians could now legitimately hold too high for Israel to reach.

The latest nine-month peace effort under Secretary John Kerry’s leadership was truly impressive, if Ben Birnbaum and Amir Tibon’s retelling of it in The New Republic is accurate. Kerry showed a much more nuanced understanding of how both sides worked, and what their actual rather than declared needs would be. And the results bore out this more intelligent approach by getting much further than Obama’s two prior attempts.

Yet Kerry’s strategy was equally flawed because it followed the same expectation that Israeli concessions would be met with Palestinian concessions, demonstrating the mistaken premise that the two sides are partners in peace. Indeed, Kerry had to secure initial concessions just to get the two sides to the table in order to discuss real concessions.

First, Kerry proposed a settlement “slowdown” to the Palestinians, which they shunned, insisting on a settlement freeze Kerry knew was off the Israeli table. He then convinced Israel to release 104 Palestinian prisoners. This was a massive concession for Israel, and an especially sensitive and symbolic one, as many of them had been convicted of killing or conspiring to kill Israelis. And even before the Palestinian leadership had voted on these conditions, Kerry announced on television that negotiations were beginning.

While Israel would be unable to recapture those 104 prisoners if the talks went south, the Palestinian “concession” was easily reversible: They promised to halt their campaign to join various bodies at the United Nations. When the Palestinian Authority broke this promise, the talks collapsed, while about 80 percent of the 104 convicted Palestinian criminals and terrorists were free.

Unlike 2000 and 2008, which were comprehensive unilateral offers requiring no prior concession, the Obama administration has now established tangible Israeli concessions as the minimum expectation for even nominal Palestinian involvement. The administration’s tacit, if not active, support of including Hamas in Palestinian governance may well end up creating another problematic expectation for any future Palestinian government.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas greets U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry as he arrives for a meeting in Amman, Jordan, on June 29, 2013. Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia

It seems, then, that despite Kerry’s greater understanding of the people and the issues surrounding the conflict, he still mistakenly expected that U.S. leadership could overcome Israeli and Palestinian hesitation. According to The New Republic, Kerry’s envoy Martin Indyk said afterward that the Americans “definitely tested the proposition that American involvement, creativity, high-level engagement with the leaders, intensive negotiations—all of the things the U.S. can bring to the table—could achieve peace. And it wasn’t enough.” The great expectation that American leadership could produce a solution was broken again.

The New Republic story also reported that, in 2013, the American president told the Israeli president that everywhere he went in the world “people talk about it…. The international community waited for the U.S. elections to be over, and then the elections in Israel—and now it’s expecting us to lead an effort towards peace. I want to go for it.”

This is an unfortunate statement of incredible arrogance. During his first year in office, Obama set the record for the most international trips in the first year of a presidential term. He followed that up with many more trips over the next three years. Yet when he told Peres that the international community is expecting America to lead an effort towards peace, he was visiting Israel for the first time during his presidency. While he had heard expectations of U.S. leadership everywhere he went in the world, he had been neither to Israel nor the Palestinian territories in order to hear what their expectations were. It was the expectations of the world that drove Obama, not any Israeli or Palestinian expectations. Had the president asked the parties to the conflict what their expectations of America were and acted on their answers, it seems unlikely that Kerry would have been given the green light to attempt new negotiations.

This was not the first time America failed in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Nor was it the first time this administration in particular, with its poor relations with Israeli and Palestinian leaders, and its poor standing in Israeli, Palestinian, and Arab public opinion, thought it knew something previous administrations did not. And it was not the first time that this failure ended up being far too costly to justify the pyrrhic victory of bringing the two sides to the table.

The outcome of the Kerry Initiative, in fact, exposes just how frustrated Israelis and Palestinians are with living through round after round of underwhelming outcomes of a political process they are told is the only way to solve their problems. As in 2000, 2008-2009, and 2012, the failure of the political process in 2014 was immediately followed by outrage, violence, and death.

Hopefully, the end of the current Israel-Hamas war will not inspire a renewed peace process championed as “the last best chance for peace” or “needed now more than ever.” This has been heard before, is aimed at people increasingly aware that the chances of success get slimmer with every new round of negotiations, and is intended to force both sides to make the hard choices they are clearly not prepared to make. If it is forced upon them again, the chances of success will be even slimmer than they were when Kerry kicked off his effort last year.

Moreover, the effort would be another painful reminder of the unrealized expectation of peace through a political process, which could very well set off a worse round of violence than we are witnessing now. Allowing the two sides a breather may actually be more productive in the long run, and would certainly be a better informed response than another counterproductive effort at forcing the two sides to a table at which neither wants to sit.

![]()

Banner Photo: U.S. Department of State / Wikimedia