The astonishing power of Leonard Cohen’s lyrics came from his ability to infuse ancient texts and methods with modern sensibilities.

In 2009, at the end of his last concert in Israel, Leonard Cohen blessed the crowd. Stretching his arms out over the sold-out audience, Cohen split his fingers into the shape of the Hebrew letter shin and softly intoned in his raspy baritone a series of Hebrew words well over 2,000 years old:

May the Lord bless you and protect you

May his face shine upon you and be gracious to you

May he lift his face toward you and bring peace upon you

It was the Birkat HaKohanim, the Priestly Blessing, lifted from the book of Numbers, discovered on metal scrolls dating from the First Temple Period, and recited only by those who, like Cohen, are descendants of the ancient priests of Israel.

It was an electric moment, bringing the crowd together with the artist in their own native and very ancient language. And it was unquestionably appropriate for another reason: Leonard Cohen was and will likely remain for some time the most openly Jewish artist in English-language pop music.

Cohen, who died November 7 at the age of 82, was an anomalous artist in many ways. In a musical world that relishes slight confections sung by beautiful young things of questionable talent, Cohen’s work was unabashedly adult, sophisticated, and often notably depressing. His looks were, one might say, an acquired taste. As Cohen wrote of Janis Joplin, “You told me again you preferred handsome men/But for me you would make an exception.” Nonetheless, Cohen somehow managed to write one of the most covered songs of all time (“Hallelujah”) and sustain a successful recording career for decades.

He was also Jewish to the point of exhibitionism. In a world in which many Jewish artists seek to hide their origins, Cohen reveled in it: never changing his name, including numerous examples of Jewish imagery and language in his work, and even writing impishly mischievous lines like “I’m the little Jew who wrote the Bible.” He was reported to be deeply wounded by his idol Bob Dylan’s brief conversion to born-again Christianity, though one imagines that, like everything else in his life, he eventually got over it.

As a recent profile in The New Yorker noted, Cohen’s Judaism came early and often. He was born into a family that was at least nominally Orthodox. His paternal grandfather was “probably the most significant Jew in Canada” and “founder of a range of Jewish institutions.” Indeed, Cohen said, “I grew up in a synagogue that my ancestors built.” His maternal grandfather was a Talmud scholar who wrote a “Lexicon of Hebrew Homonyms” as well as a book of rabbinic thought Cohen happily lent to his rabbi. At the same time, his father worked in the quintessentially Jewish garment industry, perhaps giving his son a taste in fine clothes as, to the end of his life, Cohen was always meticulously turned out in public.

All of this, Cohen told The New Yorker, gave him “a deep tribal sense.” It lasted until the end of his life. As the profile notes, in his final days Cohen was, if anything, deepening this tribal sense. He was spending two days a week at synagogue and reading “deeply in a multivolume edition of the Zohar, the principal text of Jewish mysticism,” a book unserious students of Judaism find completely incomprehensible, as well as Gershom Scholem’s definitive biography of the 17th century mystic and false messiah Shabbetai Tzvi.

This predilection for Jewish mysticism in particular seems to have been a constant throughout Cohen’s life, influencing his songs in ways that non-experts may not have understood, but unquestionably felt. The Kabbalah of Rav Yitzhak Luria seems to have had a notably strong effect on him. Jonathan Freedland described it in an Atlantic article that explored Cohen’s Jewish side. “According to the 16th century rabbi and mystic, Isaac Luria, God created vessels into which he poured his holy light,” Freedland recounted. “These vessels weren’t strong enough to contain such a powerful force and they shattered: the sparks of divine light were carried down to earth along with the broken shards.” Then, quoting a line from the song “Anthem,” he added, “Put another way: There is a crack in everything, it’s how the light gets in.”

This divine brokenness is almost a skeleton key to Cohen’s work. Speaking of his final album, You Want It Darker, released months before his death, Cohen’s rabbi Mordecai Finley wrote in the Jewish Journal:

If you are familiar with Lurianic Kabbalah, and its main heretical interpretation, Sabbateanism, you will understand this album…and I think much of his body of poetry and lyrics. I think that whatever drew Leonard to me, for me to be his rabbi these last 10 years, was that for each of us, Lurianic Kabbalah gave voice to the impossible brokenness of the human condition. The pain of the Divine breakage permeates reality. We inherit it; it inhabits us. We can deny it. Or we can study and teach it, write it and sing its mournful songs.

Certainly, Cohen could be ecumenical in his spiritual interests—he famously became a Buddhist monk for a time—but told the BBC in 2007 that his “investigations into other spiritual systems have certainly illuminated and enriched my understanding of my own tradition. I very much feel part of that tradition—and I practice that and my children practice that. So that was never in question.” Near the end of his life, he told an interviewer, “Spiritual things, baruch Hashem, have fallen into place,” using the Hebrew expression for “bless God.”

Cohen once referred to Judaism as “confession filtered through a tradition of skill and hard work,” which is as good a description of Cohen’s work as any. This elective affinity was explored by the Freedland article, which called Cohen “Judaism’s Bard.” Four songs in particular make the case for Freedland’s description.

To begin at the end, there is “You Want It Darker,” the title track of Cohen’s last album. Over backing vocals provided by members of Cohen’s synagogue, the chorus echoes the Kaddish prayer, one of the holiest in Judaism: “magnified, sanctified be thy holy name.” The lyrics explore the depredations of old age and the shattered nature of the world:

If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game

If you are the healer, it means I’m broken and lame

If thine is the glory then mine must be the shame

You want it darker

We kill the flame

But then comes the refrain “hineni, hineni,” the Hebrew word for “Here I am.” It is spoken by a multitude of characters throughout the Bible, including Adam himself. As Freedland notes, it’s “the answer Abraham, the first Jew, gave when God called out to him, asking him to sacrifice his son Isaac.…It’s the reply Moses gives when God speaks to him through the burning bush. It stands as a declaration of submission to divine authority.” As Cohen himself intones at the end of each chorus, “I’m ready, my Lord.”

Perhaps Cohen’s most blatantly Jewish song is the classic “Who By Fire,” which, as almost everyone now knows, is based on the Yom Kippur prayer Unetaneh Tokef:

On Rosh Hashanah it is inscribed,

And on Yom Kippur it is sealed.

How many shall pass away and how many shall be born,

Who shall live and who shall die,

Who shall reach the end of his days and who shall not,

Who shall perish by water and who by fire,

Who by sword and who by wild beast,

Who by famine and who by thirst,

Who by earthquake and who by plague,

Who by strangulation and who by stoning…

In Cohen’s hands, this is transformed into its modern, but equally ironic equivalent:

Who in her lonely slip, who by barbiturate,

Who in these realms of love, who by something blunt,

Who by avalanche, who by powder…

Who by brave assent, who by accident,

Who in solitude, who in this mirror,

Who by his lady’s command, who by his own hand,

Who in mortal chains, who in power…

While the prayer ends with the surety that “repentance, prayer, and charity annul the severe decree,” Cohen ends his version with the far more ominous “who shall I say is calling?” Judgment, he seems to say, is coming, but we no longer have a name for who will bring it. Fate? Destiny? God? It could be all or none of them, but the surety of the judgment, as it always is in Judaism, remains certain.

In effect, “Who By Fire” is the most prominent example of Cohen’s extraordinary ability to synthesize ancient Judaism with the modern world without vitiating the essence of either one. “Who By Fire” and Unetaneh Tokef are unquestionably about exactly the same thing, with Cohen’s serving as something of a palimpsest in which modern imagery is overlaid on the foundation of the ancient original, infusing his secular hymn with the power of religious intensity. Cohen’s secular prayer is, perhaps, the only Unetaneh Tokef our materialist and cynical world can imagine.

As Freedland points out, Cohen’s “Anthem” is deeply informed by Lurianic Kabbalah. Over a beautiful, gospel-infused chord progression, Cohen enumerates the features of a broken world:

We asked for signs

The signs were sent

The birth betrayed

The marriage spent

Yeah the widowhood

Of every government

Signs for all to see

Veering into prophetic warning, he pronounces the judgment:

I can’t run no more

With that lawless crowd

While the killers in high places

Say their prayers out loud.

But they’ve summoned up a thundercloud

And they’re gonna hear from me

Then, quite suddenly, the chorus opens up into a defiant, even joyous refrain:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

These few lines recall everything from the binding of Isaac (“forget your perfect offering”), the biblical injunction to “make a joyful noise unto the Lord,” and, of course, the Lurianic belief in the “sparks of divine light” that “were carried down to earth along with the broken shards” of the material world.

Redemption—the tikkun olam that will repair the broken world—remains possible, Cohen hints. But this is not the tikkun olam cited by many Jewish denominations today, which concentrates on changing man’s material existence. Cohen himself once pointed out that “One of the great themes of Kabbalistic thought is that the Jews are actively involved in repairing God.” In effect, “Anthem” is an anthem of tikkun, a battle cry for the messianic age.

Perhaps Cohen’s best known song today is the endlessly-covered “Hallelujah,” which has somewhere over 500 different versions by artists as diverse and sometimes unlikely as Jeff Buckley, John Cale, Jon Bon Jovi, Justin Timberlake, and k.d. lang. Yet this song more than any other points out the difference between the pop world’s generic sensibility and Cohen’s specifically Jewish one. There are, for want of a better term, a Jewish and a gentile “Hallelujah.”

The difference is in the choice of lyrics: Cohen reportedly wrote dozens of verses for the song, though he sang only four. Almost all cover versions pick and choose among these various verses. Usually, the opening verses that reference the story of David and Bathsheba (“You saw her bathing on the roof/Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you”) remain, but then the song drifts off into musings on erotic longing and even vaguely Christian imagery (“Remember when I moved in you/And the holy dove was moving too/And every breath we drew was Hallelujah”).

Cohen, however, ends the song with two climactic and quintessentially Jewish verses, neither of which is usually sung in cover versions:

You say I took the name in vain

I don’t even know the name

But if I did, well really, what’s it to you?

There’s a blaze of light

In every word

It doesn’t matter which you heard

The holy or the broken Hallelujah

I did my best, it wasn’t much

I couldn’t feel, so I tried to touch

I’ve told the truth, I didn’t come to fool you

And even though it all went wrong

I’ll stand before the Lord of Song

With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah

The wealth of Jewish imagery in these versus is stunning. There is the Ineffable Name, which can only be intoned by the high priest (the Cohen) in the Holy of Holies within the Temple, and whose true pronunciation is lost to history. There is the “blaze of light in every word,” echoing the traditional belief that the letters of the Torah are written in divine fire. There is the “holy or the broken Hallelujah,” implying both the Hallelujah of prayer and the secular Hallelujah Cohen himself is singing. And finally, there is the ecstatic resolution that the singer will “stand before the Lord of Song/with nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah.” This is the same Lord of Song who gave David, the great singer-songwriter who also ruled all of Israel, his psalms; the same Lord who now must face a defiant secular prayer born of what Cohen sometimes called the bat kol, or “divine voice” that served as his muse. Here is one of the greatest affirmations of Judaism that can be found in secular art.

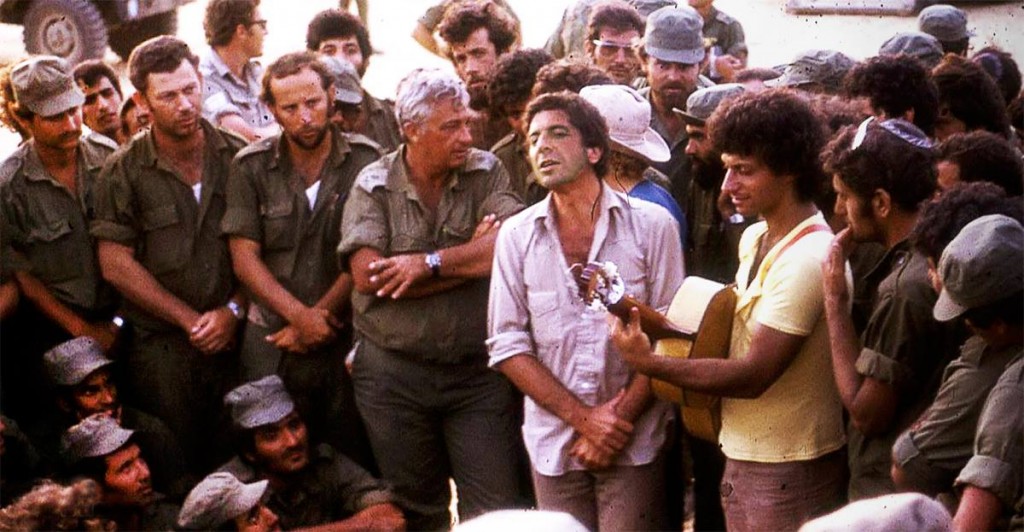

In the early 1970s, Cohen’s Jewish identity was touched by fire when he went to Israel days after the Yom Kippur War broke out. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu himself noted this upon the singer’s death, saying, “I’ll never forget how he came to sing to soldiers during the Yom Kippur War, out of a sense of solidarity.” Cohen himself said at the time, “I’ve never disguised the fact that I’m Jewish, and in any crisis in Israel I would be there. I am committed to the survival of the Jewish people.”

As a lengthy article on the subject in Israel Hayom pointed out, however, Cohen did not originally come to Israel to sing: He wanted to fight. Upon being informed that this would be inadvisable, he then sought to volunteer on a kibbutz. That also went nowhere, but Cohen was quickly snapped up by Israeli admirers and fellow musicians, beginning an odyssey that took him into the heart of the fighting in the Sinai desert. The paper notes that he “ran from base to base and from hospital to hospital.…Cohen believed it was important to get involved and speak with the soldiers, from the highest-ranking commander to the newest recruit. He admired them simply because they fought.”

This was no typical 1970s rock’n’roll tour. It was grueling and uncomfortable, with Cohen sleeping on floors and eating army rations despite offers of more amenable conditions. He categorically refused to live like anything other than an ordinary soldier, and even found himself performing under fire to soldiers fighting near the Sinai border. “In the midst of the ad-hoc show,” Israel Hayom writes, “the officers asked them to stop singing for a few moments so the soldiers could load the gun and return fire. Only afterward did they get permission to resume the show, at least until the next interruption.”

This proximity to battle, however, did lead to sometimes oddly humorous moments. A famous photograph shows Cohen and Israeli artist Matti Caspi singing to a group of soldiers deep in the Sinai. Next to Cohen stands the most improbable of all figures: Then-general and future Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who stares at Cohen with a “what the hell is this?” expression on his face. Indeed, one wonders whether Cohen’s oft-depressing lyrics really served to heighten morale on the battle lines.

All of this came with a price, however. Cohen saw the unheroic, bitter side of war, meeting wounded soldiers who had just come from the abattoir of combat with their bodies and lives permanently mutilated. “The sights were hard for everybody and particularly for Cohen,” says Israel Hayom, “who was being exposed to war for the first time in his life.”

It was this unglamorous side of combat that, as it does for many Israelis, led to Cohen’s realization of the fact that, ultimately, war is hell and peace is worth fighting for. In one of the few references to the war in his work, from the song “Night Comes On,” he sang with unflinching honesty of the cost of one of Israel’s bloodiest and most traumatic conflicts:

We were fighting in Egypt

When they signed this agreement

That nobody else had to die

There was this terrible sound

And my father went down

With a terrible wound in his side

He said, Try to go on

Take my books, take my gun

Remember, my son, how they lied

And the night comes on

It’s very calm

I’d like to pretend that my father was wrong

But you don’t want to lie, not to the young

Cohen would not lie about war, but also never engaged in the self-flagellation that the world so often demands of Israelis and Zionist Jews. This, perhaps, was what made Cohen one of Israel’s most beloved singers. While he remained a cult act in the U.S. and Europe, in Israel Cohen was nothing less than a bona fide rock star, with his work etching itself into the Israeli consciousness perhaps more than any other foreign artist. He was there for them when it mattered most, and they never forgot. Indeed, when he died, I myself heard his songs being played on almost constant rotation on Israeli radio.

And it was in Israel that Cohen gave one of his most inadvertently touching concerts. Performing in Jerusalem, Cohen was struck by the stage fright that sometimes plagued him and retreated backstage. The crowd coaxed him back by singing “Heiveinu Shalom Aleichem”—we have brought peace upon you. Cohen later said of the moment, “How sweet can an audience possibly be?”

There is no question that Cohen was, in essence, a Jewish artist, but it is difficult to ascertain precisely what kind of Jewish artist he was. It is tempting to see him as an exponent of secular Jewish culture: a Hebrew revivalist, like Bialik and Tchernichovsky, who brought biblical language into their works in a secular context; a chronicler of modern diaspora life like Philip Roth; one of the “bad boys” of Jewish literature like Norman Mailer; even as a great Yiddishist like Sholem Aleichem. It has also been said by many that Cohen was essentially a modern psalmist or even a prophet. There is, of course, something to this, with songs like “Hallelujah” and their intense Jewish spirituality, as well as prophetic admonitions like “they’ve summoned up a thundercloud/And they’re gonna hear from me.” Even his more erotic lyrics can be seen as echoes of the Song of Songs.

This is not quite enough, however. It is true that Cohen is too religious to be truly secular, but his works harken back to the biblical tradition; they reference it but are not truly of it. There is, however, one Jewish cultural tradition that perfectly fits Cohen’s work: The piyyut.

The piyyut tradition is extremely old, stretching all the way back to ancient Israel, and remained vital well into the Middle Ages. Piyyutim are poems that draw on biblical language and imagery, reworking them into new forms and, very often, setting them to original melodies. Not all of the piyyutim were sung, but many have entered the liturgy, some as prayers, others as songs whose provenance is now so old they have effectively become prayers. Some, like the work of the great poets of pre-Exilic Spain, remain purely literary. Many of them are well-known and still sung today, such as Adir Hu, Ein Keloheinu, and even, quite fittingly, Unetaneh Tokef itself.

In effect, Cohen was a composer of modern piyyutim. Like the great paytanim, he drew upon the long tradition of Jewish imagery and language—the vocabulary of Jewish art, which with the prohibition on visual images always concentrated on the literary and the musical. Cohen took fragments, the “broken shards” of the past, and arranged them into a new mosaic, renewing them and allowing them to renew him. At the same time, he addressed the modern world, just as the paytanim reworked ancient themes to address their own era. And like his ancient predecessors, Cohen turned to the old for artistic renewal and inspiration, bringing the past into the present without diminishing its power in the slightest.

Cohen lived, for example, in a world in which a Jewish state has been resurrected, so his work and his life is infused with the dynamic tension between Israel and the diaspora, a condition that did not exist for his predecessors. He lived in an irreligious era, so his work contrasts the mores of a secular existence with the esoteric powers of faith. But the essential themes of the piyyutim—the relationship between man and the divine, the pain of living in a fallen world, and the longing for redemption—always remained. He drew, one could say, from the same well: The ancient culture to which he was heir and remained loyal all his life.

In this, Cohen was almost unique among Diaspora musicians. In Israel, pop singers regularly pepper their songs with references to the Jewish literary tradition, sometimes explicitly using them to touch on spiritual matters, but in the Diaspora, this is swiftly being lost to assimilation and the pressures of globalized culture. Even Bob Dylan, despite his frequent biblical references, very rarely reached into the specifically Jewish tradition. Among English-language artists, then, Cohen was almost alone, and this may be the secret behind his strange longevity: He brought something unique to audiences both Jewish and non-Jewish, which was perhaps described best by the man himself. “What I mean to say is that you hear the bat kol,” he once said. “You hear this other deep reality singing to you all the time.…That’s a tremendous blessing, really.”

![]()

Banner Photo: Rama / Wikimedia