Over the past 40 years, members of one of the IDF’s most elite and secretive units have been behind many of Israel’s greatest military and scientific breakthroughs.

One of the most dangerous weapons aimed at Israel can’t fire a shot, but Israelis are terrified of it: Tunnels.

Before the 2014 Gaza war, the international community demanded that Israel allow concrete into Gaza, despite Israel’s objections. As Israel feared, Hamas then used that material for terrorist purposes, digging a network of underground passages, including many that crossed into Israeli territory. Israel knew the tunnels were there, but did not know exactly how to deal with them.

When terrorists began to emerge on the Israeli side of the border during the war, however, it became very clear very quickly that the tunnels were a major strategic problem and a public relations nightmare.

After the war ended, global leaders – desperate to stop the fighting for fear their own Arab populations would take to the streets and accuse them of not doing enough to protect the people of Gaza – swore up and down that if the world gave Hamas construction materials to rebuild the strip, they would not be used to dig such tunnels again.

At the same time, a special Knesset committee began investigating why the threat had been ignored by Israel for so long and what could be done about it now.

Scientists and engineers in the public sector and the IDF made various proposals: Flood the border with water from the Mediterranean. Sink steel walls 100 feet underground. Create special monitoring sensors. Call in geologists to get their thoughts. Some joked that Israel should hire Hamas to build the Tel Aviv subway in order to keep them occupied.

If any official plan came out of those meetings, it’s still a closely guarded secret.

Two years later, the great underground fear that world leaders told Israel not to worry about began to intensify.

Israelis living in towns and villages near Gaza swear they can hear the sounds of digging beneath their homes. They live in fear that terrorists will emerge and kill them, a friend, or a family member; or worse, kidnap them and bring them back to Gaza.

Unfortunately, this fear is not unreasonable. Israeli intelligence officers report that, during the war, evidence was found indicating that Hamas intended to use its tunnels to kidnap dozens of Israelis. Such evidence included plastic handcuffs and tranquilizers at the end of a tunnel explored not long before the war came to an end.

Since the beginning of this year, however, something funny began to happen to the Hamas tunnels. The terrorist group reported that five tunnels had collapsed in quick succession, killing several Hamas members. Did Israel do it? When asked, the IDF used the standard “no comment” it often uses when enemies suddenly die.

The better question might be: Is Israel capable of collapsing the tunnels as Hamas builds them?

The answer is, probably.

And there is a strong possibility that this is because of a single and very special unit within the IDF. While the Israeli army has no shortage of elite troops and elite thinkers, one unit has become known for being at the top of the pyramid: Talpiot.

Talpiot’s mission isn’t to learn how to fight. It is to learn how to think. Its recruits, now referred to by many in the Ministry of Defense as the IDF’s top priority (even more than finding and training fighter pilots), must agree to stay in the army for at least ten years. This is substantially above the norm of three years for men and two years for women, and there’s a good reason for it.

Fighting is of course a major component of the Talpiot program. Many graduates go on to command elite troops in the field, command naval vessels, and even fly F16s in combat. But mission number one can be described as intellectual.

This was the case from the moment the unit was founded. Talpiot was created by two professors who were horrified at Israel’s setbacks in the opening days of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. After Israel’s stunning victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel began to lose its military edge. France, Israel’s main weapons supplier, had abandoned the country in the face of threats from Arab nations. Israel was left without a military sponsor, while the Soviet Union showered the Arab states, especially Egypt and Syria, with state-of-the-art weapons and military training. When the two countries launched a surprise attack on Judaism’s holiest day, the result was devastating. While Israel eventually turned the tide and won the war, it was a shrill wake-up call that ended Israel’s self-confidence and sense of security.

The army had been torn apart in the war. Israel lost a fifth of its air force, more than a thousand tanks had been destroyed, and the casualty rate was shocking, with almost 3,000 soldiers killed and 8,000 wounded. Israel could not survive as a nation if it was forced to go through a war like that every few years. A new path was needed.

The two professors, Shaul Yatziv and Felix Dothan, began a campaign to convince the IDF that it needed to come up with a better way to supply itself with the research, development, and manufacture of new weapons. The country’s founding father David Ben-Gurion had always said that Israel’s military abilities had to be far ahead of its enemies’ in quality, as it would never be able to match them in quantity. Dothan and Yatziv began applying that formula to weapons development. But the army wasn’t in the mood to listen.

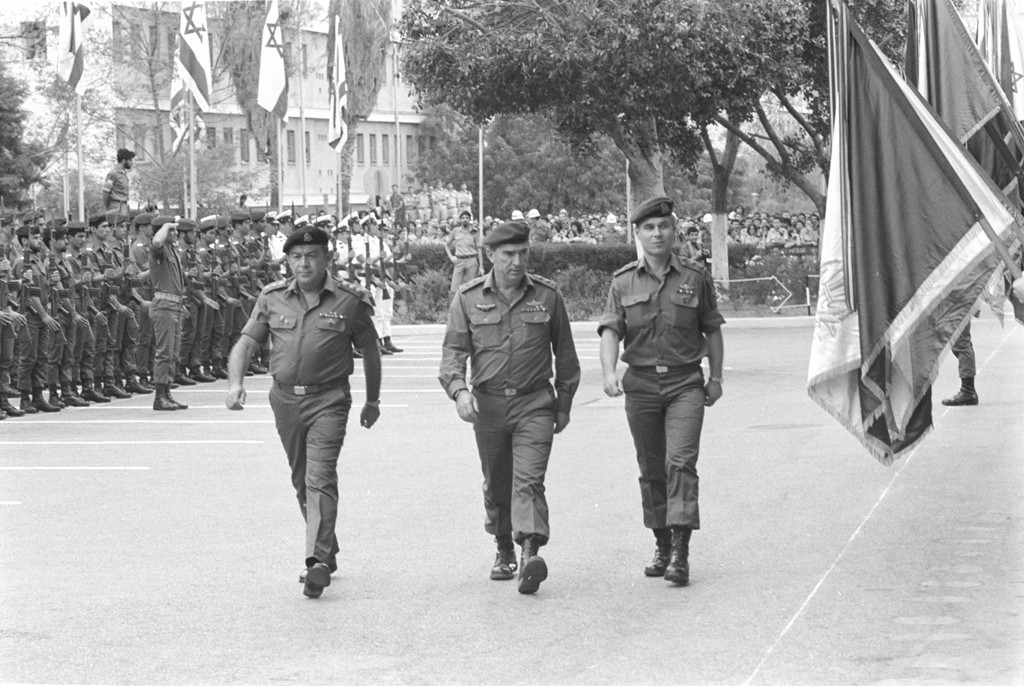

Things began to change in 1977. Menachem Begin was elected prime minister. For the first time in the history of modern Israel, the previously dominant Labor party was in the opposition, and the right-wing Likud was now in charge. Change quickly spread to the army. In particular, Gen. Rafael “Raful” Eitan was appointed IDF chief of staff.

More than his predecessors, Eitan saw tremendous value in education. To this day, an organization that helps Israel’s underprivileged teenagers get an education and find a trade while serving in the army credits Eitan with its founding. And the chief of staff approved another educational program: After first hearing about Talpiot in a briefing, Eitan was sure that it was exactly what the army and the country needed.

Soon after taking office, he asked his secretary to call Col. Benji Machness, who had run an Air Force school for pilots studying physics. Thirty-four years later, Machness described the scene: “I opened the door and Raful was waiting with General Israel Tal, sitting there. Tal was our top tank general; he invented the Merkava [tank]. I said, ‘Hello, Gen. Eitan, I’m Benji Machness.’ Eitan replied, ‘Of course, I know you.’ He didn’t even ask me to sit. He said, ‘Outside my door are two professors. I think they have a good idea. Go and do it. That’s all.’”

Dutifully, Machness left and found the two professors waiting anxiously. He told them, “Your project has been accepted, let’s get to work.” Yatziv and Dothan looked incredulous. “That’s it?” they asked. Machness said yes, and the planning stages of Talpiot began right there.

The original idea was to model the Talpiot program – named for the strong turrets referenced in the biblical Song of Songs – after the Palo Alto Research Center, commonly known as PARC. PARC was set up by Xerox in 1970 to use advanced technology to solve problems and meet the challenges of the future. After a short period, the professors came to the conclusion that Israel and the IDF did not have the kind of resources Xerox had. They needed help.

So Dothan and Yatziv took their idea to Israel’s universities. They asked the Technion, Tel Aviv University, and Hebrew University to host the program in cooperation with the army. Again, they hit a brick wall. The universities had to be convinced that they would have some control of the program and not simply hand out degrees to undeserving students.

After months of negotiations, Hebrew University was the first to agree. Deals were signed and cooperation began.

Dothan began to take the lead role in the program. But by his own admission, he wasn’t quite sure whom to recruit. He used IQ scores, high school grades, and recommendations from high school principals. He focused on finding recruits from the Israel’s academic centers in Haifa, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv.

In the early years of Talpiot, the curriculum was simple: Physics, math, and computer science. These remain the program’s main priorities. The first several classes were made up of about 25 recruits. None of them had ever heard of the program before, as it was not only new but, at this point, top secret.

The opening years of the program were difficult for the founders, the army officers in charge, and the young recruits. The founders, and especially Machness, saw the students first and foremost as soldiers. They wore uniforms to their classes at Hebrew University and took shifts guarding Talpiot’s section of the Hebrew University campus.

At first, the administrators were over-zealous. They gave the cadets too much to learn in too short a time, the expectations were too high, and the pressure was too great. The first-year dropout rate hit 35 percent.

Then the program came under fire for not finding “team players.” Put simply, the high-IQ recruits often lacked social skills.

One of the most famous Talpiot graduates is a man named Eli Mintz, who went on to found Compugen, a company that did industry-changing work in the field of DNA sequencing and is still listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange. Mintz characterizes the early Talpiot recruits as “very strange. It was twenty eccentric nerds put together and then told by army officers – who often had no idea what we were working on or how we were doing it – to ‘get along.’”

David Kutasov, an early graduate of Talpiot who is now a physics professor at the University of Chicago.

“Getting along” proved to be a formidable challenge. “Like many others in the program, I had come from environments where I thought I was always the smartest,” Mintz confessed. “So when you’re finally in a place where you think, ‘Wow, I’m not the smartest guy in the room,’ it was great. It was a new challenge.” Looking back, he believes that learning to work with others who were smarter than him was the most important thing Talpiot taught him. “But not everyone was programmed to think like that,” he said, “and it led to personality problems.”

Those “personality problems” would soon be addressed. After a few years, Talpiot recruiters added a crucial new phase to the process. They wanted to see which candidates could work well as a group under challenging conditions. To this day, these tests are performed by Talpiot graduates. They consist, for example, of working with team members to come up with as many ways as they can think of to use a bicycle or a shoe. Others include using children’s building blocks to construct something. All of this occurs under tight deadlines, sometimes in hot rooms. To add tension and pressure to the situation, former Talpiot graduates are lurking behind, recording every move and every word – or at least the candidates are made to feel like they are.

By Talpiot’s sixth or seventh year, recruiting became more formalized. Professors Yatziv and Dothan knew who they were looking for and how to find them. And by then there were actual Talpiot graduates with a bigger say in the program. That was valuable because their tangible experience led to practical revisions in the selection process.

Then came the idea for “The Interview.”

The idea came about because, ten years into the program, the army’s needs were changing. Talpiot’s officers had to make adjustments to their list of desirable qualities. Teamwork was becoming an even bigger part of the equation, because different kinds of systems had to be integrated into different units and the army needed young talent to manage these projects. They needed natural leaders who were also book-smart and patriotic.

Picking the right 20 or 25 people was becoming more and more important. “Suddenly, we had to start looking for a new combination of attributes,” said Avi Poleg, a Talpiot graduate who later became its leader. In addition to high cognitive scores and scientific thinking, they were looking for people who could lead: Officer testing and personality exams became crucial.

“I wanted to check motivation, moral value, and, of course, personality,” Poleg said.

We would run intense social simulations in which the candidate was put into a high-pressure leadership position. How do you try to motivate your classmates who might be falling behind? How do you deal with those who refuse to take part in a certain project or activity? My goal here was to see how candidates coped with social issues, leadership issues, and paying attention to everyone. I needed to be confident that the candidates I picked would be creative, intelligent, and inventive with the ability to move from one area to another, and be able to take leadership in a group while being part of that group. It was also critical to get a sense of how cadets might act when having to deal with someone above them and below them. Finally, I also needed a sense of their moral values and willingness to make a contribution to their country and society. I was always confident I could move the right students forward.

The way to find such qualities was “The Interview.” The procedure itself was a trying 30 minutes to an hour in length. After narrowing down a list of one year’s Talpiot candidates from 5,000 to about 100, the final applicants would be forced to sit in a cold university hallway for hours over several days, while one by one, they would be called in to a small room. When they entered, they saw they were surrounded by high-ranking army officers, as well as professors from Hebrew University who helped teach courses and coordinated with the army.

The officer leading the interview might say something to the nervous teenager like “tell me something interesting that you saw last month that you didn’t know, what you learned about it, and how you increased your knowledge. Maybe an interesting instrument, an interesting science program you watched on television, an interesting article you read about science.” This was just the starting point. Poleg says he would use the answer to evaluate the level of the candidate’s curiosity and how far he’d go to satisfy that curiosity. “I was looking to see if the candidate made a real effort to investigate,” he says.

Poleg believed that an incisive committee interview gave him the best sense of the candidate. In one memorable instance, a candidate had not done particularly well on previous tests, but Poleg gave him a simulation.

He started to flourish….he was so enthusiastic and really animated. “I would do this and I would do that…” It was as if he were suddenly conducting an orchestra; as if he had found his voice right then and there in front of the committee. This was exactly the answer I was looking for. He has it! I viewed the committee in part as a trainer to pull something out of a candidate, and I used similar methods as a commander and educator once those potential recruits were in the program.

From 1985 on, women were also recruited for the program. Since then, scores of young women have successfully graduated. When a young woman being tested told the committee she spoke Italian, they were impressed, because unlike English or Arabic, Italian is not a language most Israelis learn to speak. Upon hearing this, one member of the committee asked her, “How many people have seen Michelangelo’s statue ‘David’ in the Galleria dell’Academia in Florence?”

Another candidate who was ultimately accepted says, “I was told, ‘Give me the name of a scientist that you look up to and would like to emulate.’ I thought to myself, don’t pick Einstein, don’t pick Einstein, don’t pick Einstein…but I panicked and Einstein it was. I then proceeded to pretty much make up an answer, but the key was to sound confident and competent. They all probably laughed at me after I left the room.”

Once the candidates have been accepted, they go to basic training for a few weeks, then hit the books for three years. There are no vacations from the intense training. But there are times when the cadets leave the classroom.

They visit dozens of army, air force, and naval units throughout the IDF in order to see the challenges faced by soldiers in the field. As Talpiot cadets go from unit to unit, they see what soldiers in the artillery units are doing and learn how heavy a shell is. They learn how a fighter pilot completes his mission and about the weapons attached to the plane. They hit the sea with the Israeli Navy and train with paratroopers.

One Talpiot graduate remembers going back to his small town in Northern Israel and telling his friends, “I did your training and your training and yours….” The goal is to create soldiers who have a unique understanding of both academic and field training, so they can take what they learned from both sides of the equation.

But while all Talpiot recruits do the mandatory physics, mathematics, and computer science courses combined with mandatory unit-by-unit military training, a few dozen Talpiot recruits go further than that.

For many young Israelis, defending their country and the Jewish people is part of the passage to adulthood. Joining an elite army unit or the Air Force is a goal they set for themselves and fantasize about for years. As a result, some of the 17-year-olds have misgivings about joining Talpiot. They think it means giving up their dreams of going into elite combat units. But the Ministry of Defense and Talpiot’s recruiters assure them they not only don’t have to give up on those dreams. In fact, they’re encouraged to pursue them.

One example is a young man named Arik Czerniak. He has had enormous success in civilian life since leaving Talpiot. But while he was going through the approval process, he was wracked with doubts, because he had always wanted to be a fighter pilot.

As the day of his induction approached, he was invited to come to Talpiot for early testing. When he got there, the officers asked him what he wanted to do. Czerniak was forthright: “‘I want to be a fighter pilot.”

“No problem,” they laughed, “you can do both.”

After each testing session and interview, Czerniak would ask, “Can I still be a pilot?” He wanted to make sure the answer would always be yes, and it was. “They were true to their word,” Czerniak recalled.

While he was waiting to hear back from Talpiot, he accepted an invitation to try out for flight school. “In the air force, the training was seven days, with 600 people,” he said.

They put you in uniform. You spend the day running around, following orders. There’s no English word for what we had to do, but it translates to “advancement by the legs.” You see that tree? You have twenty seconds to run there and back: GO! You didn’t make it. Do it again! There were a lot of group activities and tests like digging holes, solving puzzles, hanging from monkey bars; everyone hangs and you see who falls first and last. There’s really no sleeping – they woke us up after a two-hour rest.

Czerniak made it past all the hurdles and was accepted into the Air Force program. But then he thought to himself, “Thanks, guys, this is a good failsafe, but now I’m really hoping to get into Talpiot.” As he graduated high school, he still didn’t have an answer. One day in the early summer, he was playing on his computer when the call came in. “Congratulations, you’ve been accepted to Talpiot’s fifteenth class.” His first question was, “Can I still be a pilot?”

After completing his first three years in Talpiot and a degree from Hebrew University, Czerniak was expected to do six months of research and development on radar systems for the F16. But the people running the flight school at that point said, “Enough is enough. If you want to be a pilot, you have to come now.” The bureaucratic barriers were crossed, the documents were signed, and Arik Czerniak was off to start army service again from square one. (The Ministry of Defense later considered this a bad decision. In the years afterward, with few exceptions, Talpiot graduates would have to do some work in research and development before moving on to combat units.)

Czerniak learned to fly. He was certified for the F4 Phantom shortly before the plane was phased out. But he then learned to fly training planes and now teaches pilots how to dogfight. A few times a month, he goes up to do battle drills. While it is unlikely that an Israeli pilot will find himself in that kind of close-in combat due to the use of advanced long range air-to-air missiles, it is a skill all Israeli pilots must learn and practice. “If tomorrow two F16s – one from Egypt, one from Israel – would get in close range there would be a dogfight,” he says. “The dogfighting I teach is like teaching someone to dribble. You’re not firing bullets, of course. Your goal is to take a picture of the other guy in your gun sights. You’re behind him, three hundred meters, he’s squiggling in your gun sight, and it’s all captured on video. When you go down, you debrief to find out who won, who lost, and why.”

To Czerniak, training pilots how to dogfight is a job similar to any other. He admits, however, to being angry in the rare instances when he loses.

Another Talpiot graduate has never lost in the air. (For security reasons, I won’t use his name) After graduating from Talpiot, his superiors at the Ministry of Defense encouraged him to go to flight school. Again there were bureaucratic hurdles to cross, but this fighter pilot managed to do so. His mission assignments are still classified, but he was active while Israel fought in Gaza in the south and against Hezbollah in the north, so it’s not hard to imagine the kind of work he was doing.

Several Talpiot graduates have served in naval combat units; others have commanded Israel’s fast-moving, heavily armed naval ships. The Navy is a particularly good fit for a Talpiot graduate, since it requires someone who can multitask extremely well. This includes being able to out-think and out-strategize an enemy, and understand navigation, complicated missile systems, and, perhaps most importantly, the electronic countermeasures that are a ship’s main form of protection.

A recent head of Talpiot, also a former cadet, shied away from research and development. Instead, he wanted to hit the field in order to sign up for a special Air Force unit called Shaldag. He took his physics, mathematics, and computer science knowledge along with his machine gun to places we’ll likely never know. It was his unit’s job to paint targets from the ground with a laser so that pilots can more easily find and destroy their targets from above. This kind of weapon is especially critical, because Israel is particularly sensitive to civilian casualties. Anything that makes a bomb hit its correct target in order to save civilian life is very important.

Yet another Talpiot graduate had always wanted to enter “the real green army.” So after his unit-to-unit training and advanced study at Hebrew University, he became what is known as a “tank killer.”

While most of his classmates did their research and development assignments, he hit the dirt, literally. He was trained to lead small teams deep into enemy territory, hide for several days, and then destroy tanks with extremely accurate shoulder-fired missiles that can hit their targets from miles away. The main weapon used by this unit is called “the Tammuz.” “The missile is guided by a television control,” the young man in question says. “You have a camera at the head of the missile and you just maneuver the missile to the target. For me, it was a great combination of state-of-the-art technology and a field-focused unit.” He’s now a lieutenant-colonel in the reserves, in charge of up to 400 men.

These four graduates of the program are shining examples of success, say officials high up in the Ministry of Defense. They took their academic training straight into the battlefield, where they used that knowledge. Then, in many cases, they brought it home to the lab, where they can develop the weapons of the future based on their knowledge of both theory and real combat. Nobody knows what a combat soldier needs better than a combat soldier. And nobody can make and design better tools of war than people who have personally been in combat.

While many Talpiot graduates do go into battlefield units, many others defend Israel in less high-profile ways. Missile defense, for example, has become a major area of focus for them. MAFAT – a Hebrew acronym that stands for the Administration for the Development of Weapons and Technological Infrastructure – is in charge of making the weapons of the future. Later this year, Ofir Shoham, an early graduate of Talpiot, will step down as its head after six extremely successful years.

MAFAT was developed in order to give Israel the qualitative military edge it needs to survive, particularly in the area of missile defense. It has developed systems like Arrow, David’s Sling, and the famous Iron Dome. The Arrow anti-ballistic missile system was designed to stop long-range missiles from countries like Iran. David’s Sling is just now becoming operational. Its goal is to stop the threat of medium-range missiles like the thousands Hezbollah has pledged to fire at Israel. Iron Dome was developed to knock out the kind of short-range projectiles fired from Gaza that have caused so much hardship in southern Israel.

Since coming to MAFAT, Shoham guided all three of these missile defense projects, using other Talpiot graduates in research and development labs, and in the field. On his watch, Arrow and David’s Sling made major strides.

Iron Dome, however, changed Israel’s strategic thinking in the south. Instead of constantly being on war footing along the Gaza border, the IDF can rely on the nine operational batteries deployed during Shoham’s tenure. Iron Dome now has a 95 percent success rate, and the Ministry of Defense believes this can be increased to 100 percent. This saves lives and resources, and allows the Israeli government the luxury of not having to send ground troops into Gaza to fight Hamas and other terror groups after each and every rocket barrage.

Cybersecurity is another area in which Talpiot graduates have made their mark. In August of 2011, Eviatar Matania, known as “the right hand of Talpiot,” was appointed the head of the newly created Israel National Cyber Bureau (INCB), reporting directly to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

The INCB was set up to provide the prime minister with advice on managing this new and crucial threat, against which both defensive and offensive strategies are needed. The INCB is also charged with coming up with ways to make life “continue as normal” if Israel is hit with a massive and successful cyber-attack, just as the Home Front Command is expected to do if and when Israel comes under physical assault.

Another reason for the creation of the INCB was to expand Israel’s lead over its enemies in the field of cyber-warfare. As Israel’s enemies grow their own cyber capabilities, the INCB must maintain the qualitative edge so critical to Israel’s survival.

Matania was invited to a meeting of the Israeli cabinet in November 2011, shortly after he became head of the INCB. He told members of the government that cyber-attacks are “a broad threat to human society. While this is a challenge to the state, it is also an economic opportunity. The more we invest in academia and industry, the greater the return we will receive, from both economic and security perspectives.” Prime Minister Netanyahu agreed, saying,

Israel is a significant force in cyberspace.…Just as we developed the unprecedented Iron Dome system that successfully intercepts missiles, we are developing a kind of “digital Iron Dome” in order to defend the country against attacks on our computer systems. The INCB is designed – first and foremost – to organize defensive capabilities based on cooperation between three elements: Security capability, the business community and the academic world.

In 2012, Matania built a national cyber situation room to assess threats launched against Israel from foreign computers. Its goal is to have one central place where Israel’s political leaders see the full picture of what is threatening the state and what is being done to protect it. It is also where high-ranking military officers, government officials, and business leaders can come to share information.

In addition, the INCB works closely with Israeli software companies to protect the nation from the growing threat of hackers working for hostile governments and terrorist groups, as well as lone wolves trolling the Internet.

Another of Matania’s initial goals was to create clear and direct links between the bureau and computer scientists working in Israeli industry and at top Israeli universities. This multi-system, multi-organization kind of project management is an approach Matania developed in Talpiot, where cooperation and sharing information are highly prized.

Eviatar Matania has wisely used the bureau to help advertise Israel’s prowess in global cybersecurity, creating thousands of jobs and billions of shekels in revenue. It also serves as an arm that cooperates with friendly foreign countries and shares information about threats and enemies, much like Israel’s intelligence agencies. The INCB also serves as a gateway for foreign investment in Israeli’s technology sector.

Talpiot graduates have also been at the forefront of creating new weapons for the average soldier in the field, from better helmets to more powerful explosives. They have had a hand in every minor and major innovation that helps the IDF and Israel’s intelligence services.

One graduate named Matan Arazi became very interested in the capability of computers while he was a boy growing up in Japan (his father was in the diplomatic corps). When it was time to return home and prepare for the army, Arazi set his sights on Talpiot. Years after leaving the army he said, “The most amazing thing about Talpiot is that the tools you learn to use can really help you make a one percent difference in the battlefield. Think about that. A one percent difference. An infantryman can’t make a one percent difference. Maybe a pilot in a small engagement concerning a major target can make that kind of difference, but [Talpiot alums] are doing it constantly, day by day, on many different projects. In many ways, we can be the difference between life and death for hundreds or even thousands of people.”

To make a contribution like that, you first have to be confident. You have to believe something is possible, even if certain tasks seem impossible. The idea that “you can do anything” is instilled in Talpiot recruits. “And if you can’t do it,” chuckles Matan, “you know that another Talpiot graduate either has or is on the verge of doing it. Nothing is impossible.”

While many of the men and women that make it through Talpiot would have been a success in life without the program, everyone agrees Talpiot gave them a tremendous advantage once they left the army. First off, the Talpiot alumni network is a powerful weapon. Graduates say they are never more than one degree of separation from any answer they need if they can’t find it themselves, and two degrees of separation from the financing they need for a new corporate start-up, a partner, or an appropriate job applicant or recommendation.

As a result, Talpiot graduates have gone on to create dozens of successful corporations. Among them is Check Point Software Technologies, founded by Marius Nacht in the Tel Aviv apartment of a friend’s grandmother. It became a $15 billion company that now keeps much of the world’s computer systems and mobile networks safe behind a firewall. Compugen helps drug companies create more effective pharmaceuticals through its one-of-a-kind DNA sequencing process. Another early corporate success was the XIV storage system, developed by members of Talpiot’s fourteenth class and sold to IBM for a reported $350 million. Apple is another company that took advantage of a Talpiot creation – buying memory company Anobit from Talpiot graduate Ariel Maislos for almost $400 million. Listings on U.S. exchanges and nine-figure exits have become the norm for Talpiot-created start-ups.

The success of Talpiot isn’t a fluke. It’s a proven formula that has worked over and over again for successful graduate after successful graduate. While the program itself and the reason for it – Israel’s security – can’t be emulated, many other aspects of it probably can.

But it requires a new way of thinking – an Israeli way of thinking. A way of thinking that doesn’t put so much pressure on immediate accomplishment and success. It’s a model where a subject is given the room and permission to fail, so long as the student or employee learns from that failure.

David Kutasov was an early graduate of the program who became a physics professor. After spending time at Princeton, he moved to the University of Chicago, where, he says, “I have the same job as Sheldon Cooper in The Big Bang Theory, the weird skinny guy. My job is to find out how the universe came into being.”

He also has an easy way to explain why Talpiot is so successful compared to the American model of elite education.

A lot of kids I see these days – even at top American universities – are too conventional and not original. In Talpiot, they beat it out of you and push you toward originality. Now let’s look at the American system. My daughter was admitted to MIT for engineering. But of her class, only she wants to be an engineer. The rest want to get their MBA, but they stayed with the herd and applied to MIT. Another example: In Manhattan you need the right preschool to get to Dalton, to get to Harvard, to get to the right law school. The system breeds unoriginal professionals, and it only gets you so far. It seems the most important tech leaders in the US didn’t finish college at all. Steve Jobs dropped out. Bill Gates dropped out. Look at all these MBAs betting on credit default swaps. Didn’t anyone ask “Is this a good idea?” The system breeds followers and not leaders. On the other hand, Talpiot consistently breeds leaders. Talpiot emphasizes originality. They bring in people to tell you about what’s going on in some branch of the army, then ask you how you would do it differently. They keep challenging you all the time. It’s in the genes of the program.

Talpiot’s doctrine of high standards, high achievement, originality, and innovation has affected both Israel and the world. It has influenced all aspects of Israel’s military, but also civilian areas like health care, technology, and the sciences. It has produced a new intellectual and technological elite that has risen purely on merit. As such, it is a tribute to the Jewish state’s ability to foster talent and accomplishment that both protects its people and gives something back to the world at large.

There is only one area where Talpiot’s accomplishments have yet to have an impact: Politics. Given everything it has accomplished so far, however, people should keep an eye out. It’s probably coming soon.

![]()

Banner Photo: Jason Gewirtz