For twenty years, the government of Argentina has failed to bring to justice perpetrators of one of the deadliest anti-Semitic terror attacks of all time. Now, it appears that it is no longer trying.

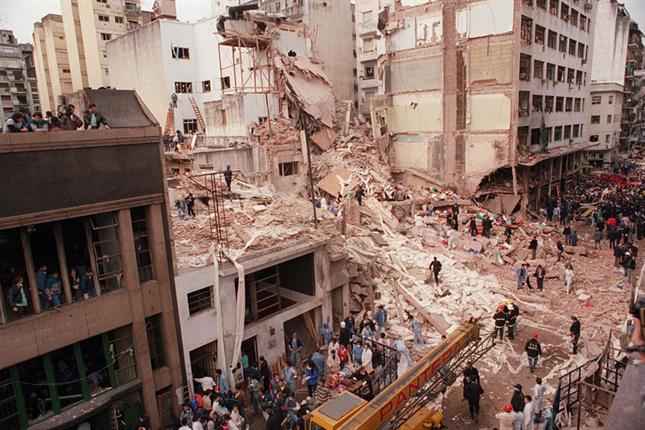

On July 18, 1994, a suicide bomber drove a van packed with explosives into the headquarters of the AMIA Jewish community organization in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The resulting blast killed 85 people and left hundreds injured. It was one of the worst incidents of anti-Semitic violence since World War II. The horrific attack is believed to have been ordered by the Iranian regime and executed by its terrorist proxies, and the ongoing betrayal of justice carried out by successive Argentine leaders who have failed to have the massacre properly investigated and prosecuted bears notable marks of anti-Semitism.

The criminal investigation into the massive terrorist attack was chaotic, plagued with accusations of cover-ups, witness tampering and bribery. In a particularly sordid climax, the investigating judge, Juan José Galeano, was removed from the investigation and now faces trial on charges arising from his handling of the investigation. A group of corrupt police officers, as well as a dealer in stolen vehicles, were eventually tried on charges of playing a secondary role in the attack. In 2004, they were all acquitted.

A subsequent Supreme Court decision revoked the acquittals of the stolen car dealer and some of the corrupt policemen. A new trial was ordered. It still hasn’t happened. The same ruling found that the initial investigation into the attack, flawed though it was, produced substantial valid evidence proving the attack was an act of terrorism.

Outside of these secondary figures, however, attention has concentrated on five Iranian citizens who are believed to have planned and staged the actual attack—and who were explicitly named by an Argentinian prosecutor in 2006. They include top officials in the Iranian government and military establishment, such as Ahmad Vahidi, Iran’s Defense Minister at the time and a former senior commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps; Imad Mughniyeh, who had been behind countless Iranian-backed terror attacks, including the 1983 Beirut bombings, and was considered the number-two in Hezbollah behind Hassan Nasrallah before his assassination in Damascus in 2008; Ali Fallahian, who served as Iran’s intelligence minister from 1989 to 1997; and Mohsen Rabbani, believed by many to be the architect and chief coordinator of what they see as Iran’s vast terror network across Latin America. The effort to extradite these men has been a long one, and has now descended into what can only be called a ritual; one that has become an established part of the Argentine political calendar.

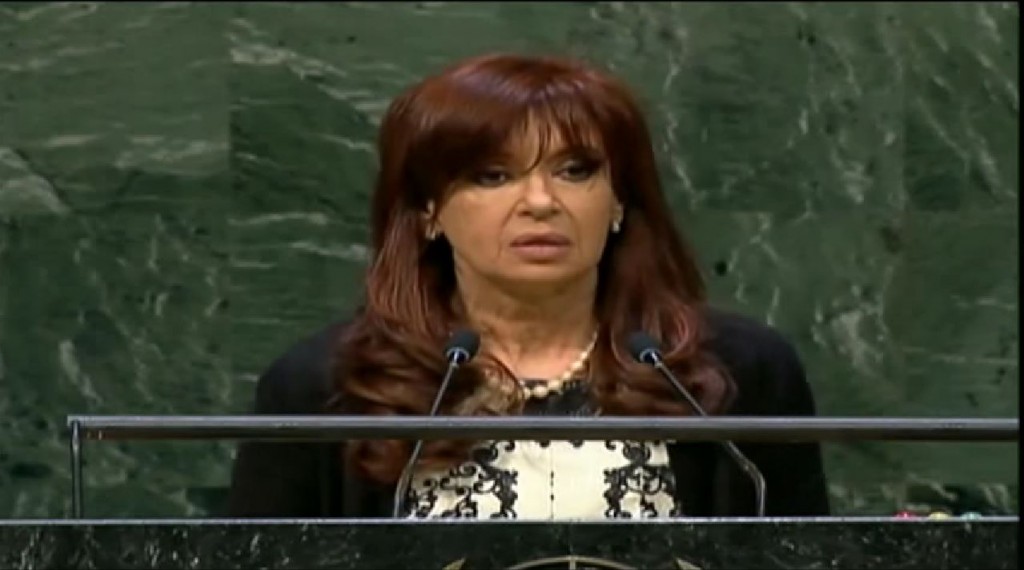

The performance of this ritual is now well established and understood by all: Using the United Nations General Assembly session as a platform, Argentina’s president requests the extradition of the suspects from Iran. In the days leading up to the speech there is speculation in the press about exactly what form of words will be used. Will it be harder or softer than last year? What form of words do the official representatives of the Argentine Jewish community want? How successful will they be in convincing the government to employ it? Then the big day comes. The president speaks. The press analyzes what was said in terms of the above-mentioned criteria and notes the caliber of the verbs and adjectives deployed. The world moves on. Nothing happens.

But in her remarks to the United Nations General Assembly on September 24 of this year, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner of Argentina made a decisive change in the ritual: She took the liberty of very publicly criticizing the representatives of the Argentine Jewish community for opposing a failed pact with Iran that would have set up a joint investigation into the massacre with the Islamic Republic.

To grasp the full nature of both the pact in question and just how outrageous was her criticism of Argentina’s Jews for their opposition to it, readers may wish to imagine the United States setting up a joint commission with the Taliban to investigate the 9/11 attacks, with the entire investigation to be carried out under Taliban supervision in Kabul. Add this to the long history of Argentinian obfuscation—including the indictment of Carlos Menem, who was president at the time of the AMIA attack, on charges of obstructing the investigation—and one can understand why anyone with a sense of decency, much less the actual community that had been targeted, would be infuriated at such a deal. Yet when the Jewish community voiced opposition to it, this is what Argentina’s president said to the nations of the world:

What happened when we signed the memorandum [with Iran]? All hell broke loose, at home and abroad. The Jewish institutions which accompany us every year suddenly turned against us when every year they had accompanied us to ask for cooperation. When it was decided that there would be cooperation by way of the pact, they accused us of complicity with the Iranian state.

The sense of betrayal triggered by these words—of the government effectively turning against the community that had been the target of the largest terror attack in the country’s history—was compounded by the fact that the president did not see fit to utter a single word of criticism of the Islamic Republic, which had perpetrated a massive terrorist attack on its sovereign soil. Indeed, she seemed to hint that the entire issue was all but closed, since all her references to the extradition request were in the past tense.

Later that day, in her remarks to the UN Security Council, Kirchner made an even more pointed allegation against the Argentine Jewish community:

When the pact was signed… organizations of the [Argentinean Jewish] community, that had always accompanied us in our demand for cooperation from the Islamic Republic of Iran, accused us of making an agreement with the Iranians. And we really started to wonder whether, when they asked us to seek cooperation from Iran, that’s what they really wanted or whether they were looking to create a casus belli.

It seems that, twenty years after it occurred, the AMIA massacre is and will remain an unsolved crime, while the president of Argentina sees fit to wonder in public whether the Jewish community might all along have been looking, not for justice, but to single-handedly start a war with Iran.

How Argentina reached such a nadir is a long story, but it is worth telling; if only as an object lesson in what not to do when confronting Iranian terrorism. It is also, unfortunately, a depressing tale of just how difficult it is to obtain justice for victims of terrorism when those victims happen to be Jews.

As noted above, the struggle to obtain justice for the victims of the AMIA massacre has been a long and frustrating one; but in the early 2000s, it looked like there was at least the possibility that it might happen.

In May 2003, Néstor Kirchner became President of Argentina. The long-serving governor of the windswept, sparsely populated, but oil-rich southern province of Santa Cruz, Kirchner promised to clean up the numerous Augean Stables on the national scene and put the country’s economy on the road to recovery after its 2002 collapse, which had resulted in mass unemployment and sky-high poverty rates.

He was succeeded by his wife, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, in 2007, though he remained a major influence on her administration until his sudden death in 2010. She is originally from La Plata, the capital of Buenos Aires Province, and met her husband when they were both studying law there in the 1970s. Though the degree to which they really participated in the revolutionary politics of the time is very much open to question, it’s clear that they like to think of themselves as having done so, and that as soon as they could they headed back to Kirchner’s native Santa Cruz, very far from the worst ravages of the 1976-1983 dictatorship, where they made their fortune in real estate trading.

Together, the Kirchner governments have been in power for over a decade, and “Kirchnerism,” their particular interpretation of Peronism, continues to be the predominant political force in Argentina to this day. The shelves of university libraries groan under the weight of books and papers devoted to attempts to understand the meaning of Peronism. Put very briefly, it is named after its founder, General Juan Perón, who originally came to power in a coup d’état but was subsequently elected President of Argentina three times. On two of those occasions, the vote was free of any serious suspicion of fraud. Perón himself was undoubtedly influenced by political ideas he picked up while a military attaché in Mussolini’s Italy, but Peronism today is not in any way fascist. It is not leftist either. Indeed, it is not anything in particular in ideological terms, beyond a certain taste for the cult of the leader and the belief that whoever wins an intra-movement struggle is always right. It serves as something of an overarching personal identity for many Argentines, compatible with a wide range of political commitments, or none at all. It may be best to simply say that it’s a way— perhaps the majority way—of being Argentine. This is reflected in “Kirchnerism,” which has little in the way of genuine ideology beyond commitment to a particular conception of human rights and state intervention, or that of friends of the government at any rate, in the economy.

Argentina President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner speaks at the United Nations, September 24, 2014. Photo: Casa Rosada / YouTube

The first round of voting in 2003 saw Kirchner defeated by former President Carlos Menem 24.5 percent to 22 percent. Knowing that he was certain to lose in the second round, Menem withdrew and left Kirchner in the odd position of assuming the presidency with only 22 percent of the vote. As a result, he found himself governing both without an electoral mandate and without an overarching ideology with which to rally his supporters. In response, he sought to formulate a strategy to establish his political legitimacy.

In September 2004, as part of this strategy, Kirchner set up a Special Prosecutor’s Office with the sole aim of finding the culprits behind the AMIA massacre. In 2006, the joint head of the office, Alberto Nisman, declared based on his exhaustive investigation that the attack had been approved at the highest levels of the Iranian regime and issued international arrest warrants for a number of its senior figures. The validity of the warrants was subsequently confirmed by Interpol.

Supporters of Iran are fond of pointing out that Nisman’s accusations relied heavily on testimony from exiled opponents of the regime. Some would say that this added to their credibility rather than subtracted from it, but this is beside the point. The real point is that it is highly unusual to demand that democratic states prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt in order to extradite a suspect. No one suggested that the fugitives be sent straight to jail upon arrival in Argentina. Extradition would simply result in a trial, with the verdict dependent on the evidence presented.

Nonetheless, the warrants seemed to be a major step forward for the victims of the massacre, their loved ones, and the Argentine Jewish community in general.

Unfortunately, this did not prove to be the case.

In 2010, three years after her election to the presidency, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner replaced phlegmatic Foreign Minister Jorge Taiana with Héctor Timerman, who is renowned, among many other things, for his personal loyalty to her, a loyalty he had previously shown to others who he thought could help him advance his career. In his first interview upon taking office, Timerman sent a clear signal that the Argentine government was not seriously pursuing the extradition of the wanted men. “The case of Iran is simple,” he said.

An Argentine court has asked for the extradition because it says it has evidence connecting [the suspects] to the attack on the AMIA and wants to question them…. It’s up to Iran to extradite them to Argentina, where they will receive due process. We have always placed our reliance on the path of justice and respect for human rights. But Iran should be aware that Argentina isn’t going to give up on its insistence on bringing these people to trial, as long as that’s what our legal system wants…. Since 2003, the government has supported the demands of the courts. We are not taking other measures. We are not going to pursue other measures.

What is notable here, apart from the aseptic tone, is how Timerman distances himself from the extradition request; an Argentine court “says” it has evidence linking the wanted men to the attack and in any case absolutely nothing is going to be done to achieve their extradition outside the narrowest of legal channels, there will be no attempt to pressure Iran in international forums, still less any efforts made to get Argentina’s neighbors that have good relations with Iran, like Venezuela and Bolivia, to intercede with the regime to get it to hand over the wanted men, and nor is there any mention of the possibility of further downgrading or ending diplomatic relations. One would think from reading the interview that the issue was a minor diplomatic spat, rather than an attempt to find and punish the murderers of dozens of Argentine citizens.

It is, of course, impossible to be sure of the real motivations and intentions of either Néstor Kirchner or Cristina Fernández de Kirchner with regard to the AMIA investigation. However, it seems undeniable that Fernández de Kirchner’s appointment of Timerman as Foreign Minister marked an important turning point in the Argentine government’s approach to the issue. Though Fernández de Kirchner’s enjoys peppering her speeches with fragments of English, she is effectively monoglot and prior to her election as president had travelled little outside Argentina. Timerman, by contrast, is well travelled, speaks impeccable English, and lived in the United States for many years. It’s not hard to imagine Timerman telling the president that, if she left matters to him, he’d bring the dispute with Iran to a successful conclusion. And from the point of view of those determined to bury the issue forever, perhaps he has.

The axe fell on January 27, 2013. In a barrage of tweets and a note on Facebook, President Fernández de Kirchner confirmed that rumors circulating since 2011 regarding secret negotiations with Iran were essentially correct. Argentina, she said, had cut a deal with Iran to settle the extradition dispute. The two countries were setting up a joint Argentine-Iranian commission comprised of jurists from both nations—with the participation of a few others from third countries—in order to “examine the documents presented” by the two sides. The proceedings of the commission were, naturally, to be held in Tehran. The Argentine court seeking extradition of the Iranian fugitives would be able to question the suspects, but only in Iran. At the end of the investigation, the commission would supposedly draw up a report that the parties would bind themselves to “take into account.”

Argentine Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman meets with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, September 28, 2013. Photo: MRECIC ARG / Wikimedia

The agreement represented an astonishing cession of sovereignty by the government of Argentina. It effectively invited the nation that has refused to extradite men suspected of murdering dozens of Argentine citizens to stand in judgment over the Argentine legal system. The reaction in the Iranian state media indicated that the regime there saw the agreement as Argentina’s abandonment of its extradition request; indeed, as its abandonment of any accusation of Iranian involvement, and a commitment to jointly investigate the murders all over again from the start.

The pact was quickly ratified by the Argentine Congress and signed into law by the president. But such was the gravity of the concessions made to Iran that the official representative bodies of the Jewish community in Argentina—the DAIA and AMIA—were shaken out of their legendary mix of torpor and eagerness to please the government of the day. They energetically rejected the pact, and filed an appeal to have it declared unconstitutional, on the grounds that it represented an intrusion on the part of the executive into the work of the judicial branch and prevented the case from being dealt with by its natural judge.

The two bodies reiterated their rejection of the pact on a number of occasions, one of them in a joint statement in February last year, in which they stated that the pact “represents a serious backward step in the search for justice for the two attacks carried out in our country.”

Just over a year later, the pact was indeed declared unconstitutional by a federal court. Although the government can still appeal the decision to the Supreme Court, it seems unlikely to do so. This is not due to any loss of enthusiasm for the pact, but because the Iranians have made no attempt to have it ratified by their own legislative body, a requirement explicitly stated in the text of the agreement.

Given the opacity of the Iranian regime, it is not possible to be sure why the Iranians negotiated the deal and then, apparently, lost interest in ratifying and implementing it. Perhaps Iran was simply buying time. The negotiations probably began soon after Timerman took office in 2010; between then and the Argentine federal court’s decision to annul the pact, the Iranians had four years during which there was no hint of any effective international pressure to extradite the suspects.

Why did Argentina debase itself so completely before the regime of the ayatollahs? The reasons are many, and first among them is Argentina’s ambiguous attitude towards victims of terrorism when those victims happen to be Jewish.

Jewish people have lived in Argentina as far back as the colonial period; the community today is largely the fruit of mass immigration from Eastern Europe and the Levant in the years 1880-1930. Estimates vary as to its exact size, but it is usually spoken of as the largest Jewish community in Latin America, and it is generally well-integrated into national life. The current Ministers for Foreign Affairs and the Economy are Jewish; and there has never been a shortage of Jewish people in general and intellectuals in particular ready to speak up in support of the Kirchners.

But this is the bright side. There is also a notably dark side to the Argentine Jewish experience. From 1976-1983, Argentina was ruled by a brutal military dictatorship whose so-called “dirty war” against revolutionaries and dissidents of all kinds laid waste to the country. A disproportionate number of its victims were Jews, among them Jacobo Timerman, Héctor Timerman’s father.

The obtuse gang of generals and admirals who ran the dirty war seized power from a democratically elected but feeble government. They did so in the context of rising political violence carried out by a menagerie of armed groups, including Left and Right forms of Peronism as well as more conventional Marxist revolutionaries. The dictatorship was determined to remake Argentina once and for all. Peronism, at least in its Leftist expression, was to be extirpated from the body politic, and garden-variety Marxists were to be crushed as well. Torture, not a practice foreign to Argentina even under democratic governments, became institutionalized. The political inconvenience attached to publicly murdering dissidents in droves was dealt with by simply “disappearing” them. In many cases they were tossed—alive and sedated—from military aircraft into the River Plate.

World Jewish Congress leaders meet with Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in Buenos Aires, June 2008. Photo: WorldJewishCongress / Wikimedia

While the generals wanted Argentina to be a Catholic state for a Catholic people, they were not particularly concerned with persecuting Jews as such, so long as they kept their heads down and mouths shut. Lower-level echelons of the national-security state they built, however, were staffed by many who held a quasi-Nazi view of the Jewish people; and they didn’t hesitate to make this known to any who fell into their hands. It’s also true that many young Jewish people had found themselves attracted to revolutionary politics of one sort or another, and they suffered the consequences when the military crackdown took place.

The armed forces left perhaps as many as 30,000 tortured and disappeared corpses behind them in 1983. The governments led by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her late husband made the reopening of these cases one of the central planks of their moral legitimacy and proof that their government puts human rights at the forefront of its concerns. Due to their efforts, hundreds of grizzled old monsters now languish in prison.

Contrast that behavior with the Kirchners’ actions on the AMIA massacre: Twenty years after the atrocity and eleven after Néstor Kirchner came to power, Argentina continues to have diplomatic and economic relations with Iran. Apart from the issuing of international arrest warrants for the suspects, the Kirchners did not lift a finger to inconvenience Iran with regard to the matter on the international stage. The passion and concern for justice with which the Kirchners pursued the criminals of the military dictatorship have been nowhere in evidence in their pursuit of the murderers of dozens of their Jewish citizens.

Ironically, fear of further Islamic terrorism may partially explain why the full pursuit of justice has not been done.

A major reason for this is ideological. The slaughterers and torturers of Argentine Jews whose deaths can be read as part of a narrative of a national revolutionary social and political struggle are being prosecuted and sentenced by the courts. But Jews killed for being Jews form no part of any such narrative, so their likely murderers receive nod after nod, wink after wink, and direct indication after direct indication that the Argentine government will never seriously pursue justice for them, and indeed is anxious to sweep the matter under the carpet.

Another ideological factor is the “anti-imperialist” and anti-American beliefs that are common in many strata of Argentine society, and particularly close to the hearts of some elements of the government’s political base. Those who hold such beliefs are inclined to have feelings towards the Iranian regime that range from a sneaking respect to frank admiration. Iran, they tell themselves, stands up to the arrogance of American power and is the sworn enemy of a nation which many of them regard as the acme of evil, i.e., Israel.

Luis D’Elía is emblematic of this line of thinking in Argentine political life. Though Néstor Kirchner fired him from a low-level ministerial position for his conspiracy theory that the case against Iran was a smokescreen to cover up for the real culprits—namely, elements of the political Right in Israel—he continues to be a prominent supporter of the government. The “social movement” which he leads has on more than one occasion provided street muscle in order to discourage opponents of the Kirchners from expressing themselves with too much vigor. He continues to appear at official government functions and public meetings, and leads demonstrations against Israel and Zionism at every opportunity. He sees Israel as an enormously powerful nation that interferes on practically a daily basis in Argentine public affairs.

An open admirer of the Iranian regime, he visited Tehran in 2010. While there, he held a “brief meeting” with Mohsen Rabbani, one of the principal suspects in the AMIA massacre, whose considerable assets in Argentina have been frozen over the course of the investigation. He described Rabbani as “a much-loved person in Floresta [a district of Buenos Aires]” indicted by “a prosecutor who responds to Zionist interests.” It’s not hard to imagine the effect of statements like this—and the visit itself—on Iran’s perception of Argentina’s seriousness on the extradition issue.

A memorial for victims of the 1994 AMIA bombing sits outside the building that replaced the one destroyed in the attack. Photo: Nbelohlavek / Wikimedia

Supporters of the Kirchners might say, “Well, what does D’Elía matter? He just has his dirt-poor followers and likes publicity.” But what matters about D’Elía is not his power or popularity; it is that his thinking represents a certain worldview that is by no means unpopular. Not many in Argentina would buy into all his conspiracy theories or his rank anti-Semitism. But quite a few would find parts of it credible and overlook the rest. And, it must be remembered, D’Elía has never been fully ostracized by the government. Indeed, he was present among the front ranks of the president’s ministers and supporters at a speech she gave shortly after her return from New York, during which she announced the appointment of one of his sidekicks to a government post related to housing.

More disturbingly, President Fernández de Kirchner herself is not immune to the kind of conspiracy thinking of which D’Elía is such a notable exponent. In her address to the nation regarding the pact with Iran, she repeated the rumor that the explosion which destroyed the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires in 1992 might not have been caused by a terrorist attack, but by explosives stored in the building itself.

The truth is that the Iranians chose well when they decided to murder Jews in Argentina and not somewhere else. It’s likely that the largely incompetent police and intelligence services still contain elements of the anti-Semitic ideology at work in the military dictatorship. Had the AMIA massacre targeted Basque or Presbyterian or some other group of Argentines with a particular ethnic or religious identity, it is inconceivable that 20 years later none of the principal culprits would have been detained.

A final factor is the simple fear of Iran and Iranian terrorism; which is, ironically, an implicit admission that the Islamic Republic was indeed responsible for the AMIA massacre. Horacio Verbitsky, for example, has expressed such sentiments. He is a journalist, but also much more than that. In particular, he was a prominent member of the “Montoneros” in the 1970s, a revolutionary Peronist movement whose mantle some see the Kirchners as having inherited. He has close relations with past and present members of their governments and is regarded as someone who both reflects and influences policy decisions. In a 2007 column, he wrote the following:

President Néstor Kirchner will dedicate a paragraph of his speech to the General Assembly of the United Nations on Tuesday to Iran. The matter in question is the most delicate that has confronted Argentina’s foreign policy in 70 years. If the sending of an old warship by Menem’s government to assist in the American expedition to the Iraqi desert in 1990 was one of the causes of the attacks on the Israeli Embassy in 1992 and on the AMIA in 1994, then the situation is even more dangerous now. The fading government of the United States has a plan to attack Iran, possibly with nuclear weapons, for obvious economic and geopolitical reasons; and all that it requires is a casus belli to present such an attack as an act of altruism. The weak indictment drawn up by prosecutor Alberto Nisman, with the agreement of the intelligence services of the United States and their counterparts here—many of whom held important positions during the dictatorship—might serve as a basis on which to seek the cooperation of Iran in the investigation into the attacks; but not for a rupture in relations nor for a direct accusation against the government of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, as has been demanded of Kirchner by a Spanish lobbyist for the Israeli government and the representatives of the Jewish community in Buenos Aires. If the first American missile launched against Iran carries greetings from Buenos Aires, then it will constitute the gravest possible error and will have easily foreseeable consequences.

Verbitsky, it seems, saw Iran as a victim of the United States, which he feared would use Nisman’s indictment as an excuse to attack Iran should Kirchner fail to express himself with due circumspection at the General Assembly.

Particularly important, however, is the very last sentence of Verbitsky’s article. The most reasonable interpretation I can think of for “easily foreseeable consequences” is a further atrocity committed against Argentines, probably Jewish Argentines. And if such consequences are “easily predictable,” it can only be because a similar pattern of events has occurred before.

In Verbitsky’s view, it clearly has: he believes that the Israeli Embassy and AMIA massacres were, at least in part, punishments for Argentina’s marginal participation in the first Gulf War. Verbitsky, a man widely reputed to be of some influence at the highest level of the governments of the Kirchners, appears to think that Argentine foreign policy and the bodies that represent its Jewish citizens should be organized in such a way as to avoid irritating the government of a foreign power. The reason is fear that this power may be angered to the extent of committing further attacks on Argentine Jews. It is depressing to have to point out that Verbitsky is himself Jewish, and would have no hesitation in mentioning this fact were anyone to accuse him of going soft on the likely murderers of the AMIA victims.

The bitter truth is that Iran has not had to try to very hard to elude its responsibility for the AMIA massacre. It is admired for its hostility towards the United States by considerable sections of the government’s support base (and in some other political sectors too). And its belief in global Jewish power meddling in other countries’ affairs fits nicely with a certain line of thought on both the Left and Right of Argentine politics: a resentment-soaked worldview that sees Argentina as having consistently been denied its place at the top level of world affairs by dark forces with varying names. Once upon a time it was the British, and then it was the Americans; today this resentment has come to be focused on a composite entity that could be called “American Imperialism-Israel-Zionism,” opposition to which is self-justifying and requires no connection to a broader dedication to human rights or any other project of human liberation. All Iran has had to do is flatly refuse to comply with Argentina’s extradition request; enter into talks that resulted in Argentina’s total capitulation to Iranian demands; and, when Argentina rushed to ratify the resulting agreement, lose interest in the matter altogether. Internal Argentine factors have taken care of the rest.

If there is any lesson to be learned from this sad tale, it is that in order to fight terrorism you have to want to fight it. That is something the Kirchner governments have shown no interest in doing, and they have suffered the consequences of moral degradation and national humiliation as a result. They appear to think that making ringing declarations of concern for justice while winking at the likely perpetrators of a terrorist massacre is a better policy. It is difficult to imagine that any future government will vary this line in any significant way.

Such a policy is not difficult to pursue in the case of an attack against Jews, who are not fully Argentine in the eyes of many. And if there were any remaining doubts about the current government’s intentions, the president buried them last month with her attacks on the Jewish community and its institutions at the United Nations.

For the victims of the AMIA attack, their survivors, and the Argentine Jewish community in general, it is unlikely that justice will ever be served. Abandoned by successive governments, rebuked by their own president, and regarded with suspicion and contempt by some of their own compatriots, they have suffered the double tragedy of an atrocity compounded by injustice.

Terrible as it is to say, were I a terrorist leader, the conclusion I would draw is that I can carry out another mass casualty attack against Argentine Jews and very likely get away with it, clean.

![]()

Banner Photo: Administración Nacional de la Seguridad Social / flickr