Qatar is hosting the 2022 World Cup despite no soccer heritage to speak of. This, along with sponsorship of some of the world’s most popular teams, is part of the country’s plan—being known as a soccer powerhouse, rather than as a country that sponsors terrorists and uses slave labor.

At the end of September, the executive committee of FIFA, the powerful governing body of world soccer, held the second of its twice-yearly meetings at the organization’s vast, sparkling headquarters in Zurich. As the 24 members walked into the glass-fronted complex, constructed at a price tag of $196 million and containing five underground floors, a meditation room, and a full-sized soccer pitch, some of them might have uneasily recalled the words of FIFA’s Swiss president, Joseph “Sepp” Blatter, at the building’s lavish opening ceremony in 2007. The glass, Blatter declared solemnly, would “allow light to shine through the building and create the transparency we all stand for.”

But transparency was the last thing on Blatter’s mind when he faced journalists at the end of the executive committee’s September deliberations. The assembled reporters were eager to learn whether Blatter would now release an internal report into how the respective Russian and Qatari bids for the 2018 and 2022 World Cup tournaments were approved by FIFA, despite numerous grave objections being raised within and outside the organization. Any expectations were quickly dampened when Blatter announced that the report’s contents would not be disclosed to the public.

As any FIFA observer will tell you, Blatter leads the charmed existence of an international executive with plenty of money at his disposal and no meaningful accountability to worry about. Technically, then, there was nothing to stop him from locking the report in a vault for eternity—but having now done so, he knows better than anyone that the chatter about what the report probably contains will only grow louder and more urgent.

When asked whether gay soccer fans would be welcomed at the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, where homosexuality is illegal, FIFA President Sepp Blatter said that gay fans “should refrain from any sexual activities.” Photo: Agência Brasil / Wikimedia

As a result, the lengthy run-ups to the next two World Cup competitions are set to be dogged by allegations that the staging rights were secured through corruption and bribery involving top FIFA executives. In the case of Russia, concrete evidence of these misdemeanors is admittedly sketchy; even so, representatives of England’s bid to stage the 2018 tournament claim that the only a handful of FIFA executive committee members bothered to read the documents they submitted, while the political analyst Stanislav Belkovsky, an opponent of Vladimir Putin’s regime, has alleged that the Kremlin was told a week before the actual FIFA vote that its bid had been successful.

When it comes to Qatar—the wealthiest country in the world, with a $200 billion budget to spend on stadiums and infrastructure for 2022—the corruption charges have been more seriously documented. Of special concern are the allegations that Mohamed bin Hammam, a Qatari member of the FIFA executive, made secret payments totaling $5 million to other committee members in advance of the 2010 FIFA vote in favor of Qatar’s bid. Hence the current pressure on Blatter to release the report, not least from its author, Michael J. Garcia, the former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, whose career highlights include the investigation of the disgraced governor of New York, Eliot Spitzer.

Frustrated by the announcement of the head of FIFA’s ethics committee that a final judgment on Qatar’s hosting of the tournament was unlikely before the spring of 2015, Garcia urged FIFA to “authorize the appropriate publication of the Report on the Inquiry into the 2018/2022 Fifa World Cup Bidding Process.” Garcia’s call was joined by other key figures from international soccer, including Sunil Gulati, the head of the United States Soccer Federation, and, notably, Prince Ali bin al-Hussein of Jordan, a FIFA vice-president, who opined on Twitter that the public has “a full right to know” the contents of Garcia’s report.

“FIFA doesn’t care about transparency,” said the leading soccer writer Simon Kuper, author of the highly-regarded Soccernomics, when I asked him why the world body would commission a report only to conceal its findings. “They might want the report for their own purposes. It’s useful to know who was corrupt, because you can punish them, or use that knowledge against them should they ever decide to run for election. FIFA also thought that by commissioning a report, it would look like they were acting against corruption.”

With Garcia’s report currently unlikely to surface in the public domain, speculation about how Qatar’s bid was successful will, for soccer wags, provide endless material to support the contention that FIFA is irredeemably corrupt. In the wider domain of Middle Eastern politics, the investigation takes on an additional layer; specifically, why Qatar, a leading sponsor of jihadi terrorist organizations like Hamas, and a serial abuser of human rights inside its own borders, has turned to soccer as the principal means of polishing and promoting its self-image as an enlightened state.

For all of its talk of fair play and respect, soccer, and the world of international sports more generally, has never shied away from conducting business with some of the most insidious regimes on the planet. During the last century, the Summer Olympics has been held in three capitals of totalitarianism, in both its national socialist and communist variations: Berlin in 1936, Moscow in 1980, and Beijing in 2008. In 1970, the World Cup was played in Mexico, two years after that country hosted the Olympics, which were held mere days after dozens of students were massacred for protesting against the ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional; the trophy was won by Brazil, who carried it back to a land disfigured by the brutal dictatorship of President Emilio Medici. In 1978, the tournament was hosted by Argentina, in a major public relations boost for that country’s military regime. As the matches were being played, Argentina’s generals were arresting as many as 200 dissidents each day, fearing that these individuals would otherwise be sought out by intrepid foreign journalists. Very few of these imprisoned souls ever saw the light of day again.

In that sense, the success of the Qatari World Cup bid simply underlines the loose relationship that international sporting bodies have always had with moral standards. There is, however, an additional, critical factor to account for: even when compared to the glory days of the late twentieth century, when stars like Brazil’s Pelé and Argentina’s Diego Maradona strutted the pitch, soccer’s thirst for commercial investment has grown astronomically. State-of-the-art stadiums, super clubs fielding players earning seven-figure monthly wages, international television broadcast deals which ensure that a viewer in America can channel-hop between live games from Germany, Spain, and Italy (by turning, for example, to the Qatari-owned beIN television sports network)—all of this requires a significant injection of capital. And capital is something the oil-drenched Qataris have on tap, in marked contrast to the afflicted, cyclical economies of Europe and the United States. As Kuper pointed out in our conversation, Qatar is also willing to spend on vital FIFA projects that garner less media attention: “If you want to host a women’s World Cup, or an Under-20 World Cup, it costs money, but Qatar can help you out.”

By readily demonstrating their seemingly bottomless largesse, the Qataris help themselves out as well. Until the early part of this decade, it’s safe to say that most soccer fans rarely, if ever, gave thought to the tiny Persian Gulf monarchy that has been ruled by the al-Thani family since the middle of the nineteenth century. But in 2011, in an extraordinary public relations coup, the Qataris began a commercial relationship with FC Barcelona, the Catalan champions of the Spanish league, who were then at their masterly peak.

The Barcelona deal was an eyebrow-raising arrangement between a wealthy, conservative petrostate and a soccer club steeped in left-wing politics and Catalan nationalism—until the Qataris came along, Barcelona steadfastly refused commercial sponsorship of their shirts, displaying instead the logo of UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund. Cannily, the Qataris opted to spend their $40 million annual sponsorship of Barcelona through the Qatar Foundation, ostensibly an educational and community organization created in 1995 by the then-Emir, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani. Everybody won: Barcelona retained their illusory non-profit image while getting a serious injection of cash, and the Qataris reveled in a bonanza of positive publicity.

As sports retailers happily fed the insatiable public appetite for child-size replica jerseys of Barcelona idols like Lionel Messi and Andres Iniesta, the Qatar Foundation, whose logo was emblazoned in generous letters on the front of the shirt, became globally recognized. In the process, Qatar’s external image transformed from that of a remote desert emirate, 94 percent of whose inhabitants are migrant workers denied the education and healthcare rights granted to Qatari citizens, into a powerhouse supporter of scientific and commercial research, whether through the Qatar Foundation or through the numerous universities, like Carnegie Mellon and Paris’s HEC business school, with campuses in Qatar. By 2013, the Qataris were so confident of their progress that they swapped out the Qatar Foundation logo on Barcelona’s shirt for that of Qatar Airways, with no objections on the part of the Barcelona management.

Emboldened by their sponsorship of Barcelona and acutely aware that the United Arab Emirates was also sinking money into European soccer, the Qataris began looking for similar investments. In 2011, Qatar Sports Investments, owned by the present emir, Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad al-Thani, purchased a 70 percent stake in the French club Paris St. Germain (PSG)—then an ailing team, and now, thanks to the Qataris and their cash, one of the most formidable sides in Europe.

According to The Guardian‘s David Conn, one year before the PSG purchase, Sheikh Tamim was invited to a lunch at the Élysée Palace hosted by Nicolas Sarkozy, then the president of France, and Michel Platini, the legendary former captain of the French national team, and now the president of UEFA, the European affiliate of FIFA. Subsequently, Platini claimed that Sarkozy was keen for the Qataris to buy PSG, but he denies that the French president’s leanings influenced his own vote in favor of the Qatar bid when FIFA decided the matter in 2010.

Without the Garcia report, we will likely never know the full extent of Platini’s role. Nor will we learn the complete story around the allegations against Mohammed Bin Hammam, the Qatari who, according to an investigation by the UK’s Sunday Times, was identified in a cache of millions of leaked emails as having paid soccer officials in the Caribbean, Africa, and the Pacific to vote for Qatar’s bid.

Said to be among those officials was Jack Warner, a Trinidadian member of the FIFA executive committee, who allegedly received $1.2 million from a company controlled by Bin Hammam. When, in 2011, FIFA attempted to head off a rapidly encircling media by suspending Bin Hammam and Warner, Warner employed a trusted Middle Eastern technique to explain his plight. “I will talk about Zionism, which probably is the most important reason why this acrid attack on Bin Hammam and me was mounted,” he told a Trinidadian newspaper.

Warner’s accusation that “Zionism” led to his downfall is a salutary reminder that with Qatari influence comes Qatari thinking. For all of its benevolent soft power projections into the Western world, whether through its commanding presence in European soccer, or its backing of the English-language version of the Al Jazeera news broadcaster, the emirate’s political calculations remain dominated by the traditional habits of Arab rulers—like blaming Israel for completely unrelated woes and, in Qatar’s case, expanding aggressively into foreign commercial markets, in order to maintain prosperity for the privileged 6 percent at home and a strong profile abroad.

“Qatar is playing a double game,” Haras Rafiq, the outreach officer for the Quilliam Foundation, a counter-extremism think tank based in London, told me. “On the one hand, its rulers are promoting a positive image of the country by, for example, hosting the 2022 World Cup and sponsoring Barcelona. On the other hand, they’re supporting and harboring extremism and terrorism in the Middle East and around the world. They also operate what I would term ‘apartheid-like’ policies domestically—go there, and you’ll see shopping malls that are for Arabs only. I, as a Muslim of Pakistani descent, can’t go into those malls.”

The most savage of Qatar’s apartheid-esque qualities lies in the treatment of its 1.4 million migrant workers. Over the last two years, reports have repeatedly emerged of barbaric working conditions in the World Cup stadiums under construction, of unsanitary and crowded living quarters, and of the myriad abuses enabled by a labor relations system, known as the kafala, which converts the employer-worker relationship into a master-slave one. A government-issued report admitted that nearly 1,000 South Asian migrant workers died in 2012 and 2013; workers who built the 43-story al-Bidda Tower, which contains the headquarters of Qatar’s World Cup organizing committee, weren’t paid for over 13 months.

Fans cheer on their teams at a qualifying match for the 2014 World Cup between Qatar and Vietnam at Qatar’s Al Sadd stadium. Photo: Vinod Divakaram / flickr

A recent Guardian article on the subject opened with a description of Nepali workers leaving for Qatar from Kathmandu’s departures terminal, while over in the arrivals hall, planes coming in from Doha unloaded coffins containing “some of their predecessors…from the cargo hold.” In September, two British human rights researchers investigating the predicament of Nepali workers, Krishna Upadhyaya and Gundev Ghimire, were detained for ten days by the Qatari authorities as they attempted to leave the country. Speaking after his release, Upadhyaya said that he and Ghimere were repeatedly asked “why we were choosing Qatar, and not the other countries. The main thing they were asking was why Qatar, why are you portraying it as a negative picture. They were most concerned about that.”

That one might expect different behavior from its law enforcement officials is a testament to Qatar’s skill in rebranding itself for a global audience. In reality, though, the country is more properly classified as Islamist. Sharia law prevails internally, along with a smattering of civil provisions inherited from the period of British rule. Along with Turkey, Qatar is the chief backer of the Muslim Brotherhood, including its Palestinian chapter, Hamas. Since Hamas seized control of Gaza in 2007, Qatar has poured millions of dollars into the Islamist organizations’ coffers. (As is well known, Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal lives in pampered exile in a luxury Doha hotel.)

Qatar’s Islamist connections stretch far beyond Hamas. A recent research report from the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs noted Qatari funding for jihadi groups in Iraq, Syria, and North Africa, including affiliates of Al Qaeda, some of whose fighters have now pledged allegiance to the Islamic State as it rampages through northern Iraq. Qatar is also notorious for providing a home to the spiritual leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, Sheikh Yusuf al Qaradawi, whose fatwas have variously targeted Jews, Shi’a Muslims, and American personnel in the Middle East.

Yet, like Turkey, Qatar remains a valued American ally in the region. As recently as last July, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel announced that Qatar was purchasing $11 billion of American weapons, including Apache helicopters and Patriot and Javelin defense systems. I asked Haras Rafiq whether this was conclusive proof that the U.S. remains unconcerned by Qatar’s involvement in terrorism financing. “I think the Americans are focused on the sharp end of preventing extremism,” he replied. “For President Obama, that means combating individuals and countries once they become a direct threat to national security, as Islamic State has. But what he’s missing is the bigger part of the countering extremism strategy, which is combating the ideological influence of extremists more generally.”

Ultimately, it is the weather—rather than more pressing concerns like its human rights record, its support for terrorism, and its role in increasing the level of corruption in the world’s most popular sport—that is best positioned to confound Qatar’s ambition of staging the World Cup in 2022. Temperatures in June, when the World Cup is played, can reach a dangerously high 112 degrees. Even for the most acclaimed athletes, playing a sport defined by physicality and speed in such conditions can be life-threatening. Indeed, this argument provided for the pretext for the latest FIFA executive committee member, Theo Zwanziger of Germany, to break ranks over the Qatari bid.

Qatar insists that it will build air-conditioned stadiums, but many soccer experts regard that as impractical. “Nobody has ever played football using air conditioning for a solid month,” Simon Kuper told me. “Your entire experience for one month, the biggest experience of your career as a player, would be air conditioned, and that’s a big uncertainty for players who are used to playing in natural temperatures.”

Another option, therefore, would be to move the World Cup from June to November, when temperatures in Qatar are more tolerable. The problem with this approach, however, is that it would play havoc with the schedules of lucrative club competitions like the English Premier League and the UEFA Champions League, all of whom compete during the winter months. In such a scenario, Qatar’s cash reserves will likely come in handy. “It would be very inconvenient, and you can bet the European leagues are going to say that,” Kuper said. “But if they can double their revenues because Qatar pays them an indemnity, then they will let it happen.”

At one of the world’s most popular soccer clubs, someone is pulling the strings. Photo: Markus Unger / flickr

With eight years to go, it is inevitable that misgivings over Qatar as the World Cup host will carry on multiplying. Yet it would be foolish to underestimate the emirate’s ability to withstand outside scrutiny and pressure. Particularly in the world of sport, as Americans rediscovered recently with the domestic violence scandals in the National Football League, commercial performance is what determines the success of an individual or an institution; setting a behavioral example and promoting concepts like “diversity” and “tolerance” is, by contrast, merely a matter of the right messaging.

That does not mean the media and various international human rights group will now shy away from the Qatari abuses they have done a marvelous job in exposing. Partly as a result of their efforts, the world now realizes that there is another Qatar that does not sit well with the airbrushed, philanthropic impression conveyed by the Qatar Foundation. Behind the Qatar of Messi and Barcelona is the Qatar of Qaradawi, jihadi preaching, and abominable violations of workers’ rights. For the time being, at least, the al-Thani family believes it can keep both.

![]()

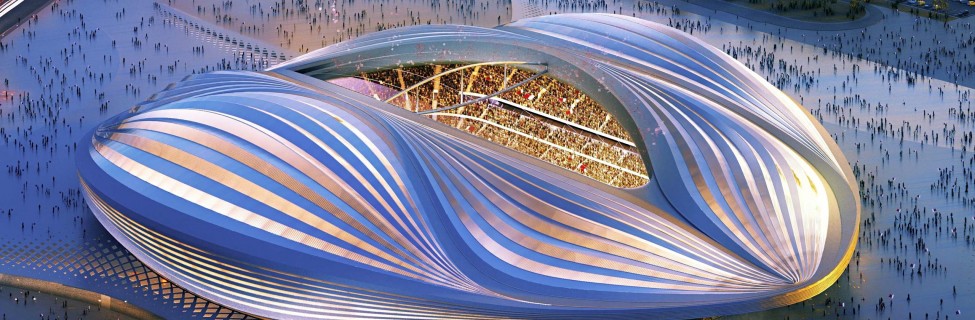

Banner Photo: AFP / Getty Images