College campuses across the country have been inundated with anti-Semitism from a new source: Yik Yak, a social media smartphone app that allows people to post anonymous messages. Yik Yak is localized — one must be within 1.5 miles of a particular Yik Yak “feed” in order to post on it. There is a specific Yik Yak feed for Stanford University, another one for Princeton University, and even one for Tel Aviv (Yik Yak is not limited to college students, although it is far more popular among them). Picture a college-only Twitter feed, but one in which everyone is anonymous.

Yik Yak was founded in 2013, and soon gained massive popularity on college campuses. The anonymity of the app encourages students to post their uncensored thoughts. Many “yaks” — as a message on Yik Yak is called — feature students worrying about classes, sharing their mental health struggles and seeking support, making jokes, or even seeking out sex. But there are also political posts. In a campus climate in which speaking one’s mind on complicated, tendentious issues can lead to social ostracization, many students appreciate the opportunity to freely share their opinions.

However, this has also led to problems. A number of schools, including Saint Louis University, Utica College in New York, and the College of Idaho, have banned Yik Yak on their campuses due to incidents of cyberbullying. Students have threatened violence on the app as well, such as promises of “Virginia Tech Part 2” (Towson University) or “shooting up the school” (Emory University). On Wednesday, two college students were arrested after using the app to threaten to shoot black students at the University of Missouri.

Yik Yak purports to be anonymous — but this is only true to a point, since the application keeps track of users’ phone numbers. Yik Yak handed the phone numbers of the men who threatened to murder black students over to the police.

Numerous anti-Semitic posts have also popped up on Yik Yak feeds at colleges across the country, but these instances have received little, if any, attention from the media, and certainly none from police. The trend does not seem to discriminate based on type of school: both San Diego State, a large public school, and Connecticut College, a small private liberal arts school, have been affected.

At Princeton, a student wrote on Yik Yak that a recent initiative to divest university funds from companies that do business in Israel “has made me feel the most unsafe to be Jewish that I have ever felt.” Another student criticized the poster for expressing her feelings: “I’m Jewish. Israel is doing some fucked up shit. I don’t feel victimized at all.” Reasonable people can disagree about Israeli policies, but apparently feeling unsafe is the price some Jewish college students must pay for Israel’s actions.

Also at Princeton: a post stating, simply, “Jewish lives matter.” And a response: “No they dont [sic].”

While much anti-Semitism on college campuses today has been disguised by a front of anti-Zionism, classical anti-Semitism — often provoked by divestment campaigns — has also reared its ugly head.

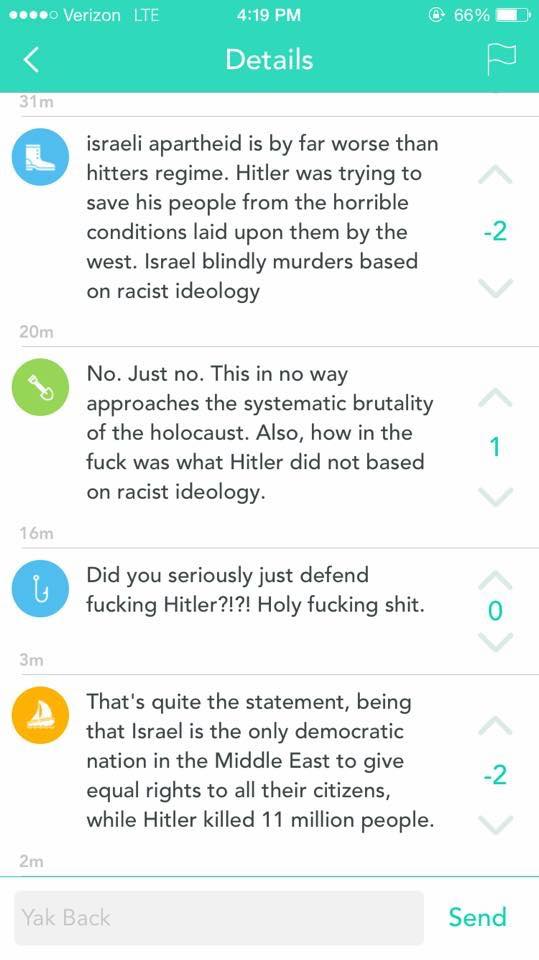

At San Diego State, a student wrote, “Israeli apartheid is by far worse than hitters [sic] regime. Hitler was trying to save his people from the horrible conditions laid upon them by the west. Israel blindly murders based on racist ideology.”

On the feed at Claremont McKenna College, near Los Angeles, students were assaulted by calls to “fire up the ovens” and at least one “Heil Hitler.”

On the feed at Claremont McKenna College, near Los Angeles, students were assaulted by calls to “fire up the ovens” and at least one “Heil Hitler.”

At the University of Chicago, a call was made to “Gas them, burn them and dismantle their power structure. Humanity cannot progress with the parasitic Jew.”

Stanford, where I am a student, is no exception. One post said “Hey, Zionist yakker, go back to Germany of the 40’s, where Zionists belong.” Another stated that “Zionism is the Protocols of the Elders of Zion manifesting into reality. It is evil, and must be talked about until it is vanquished.”

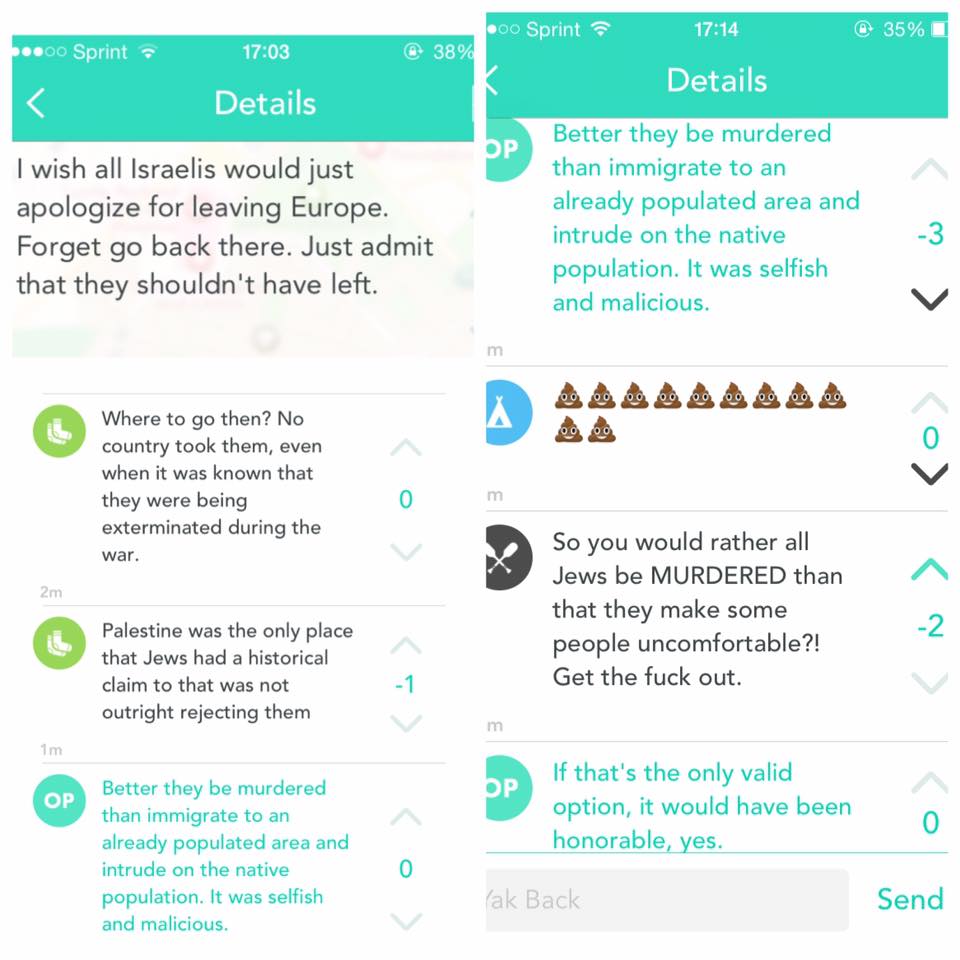

I once saw a Yik Yak post expressing the wish that “all Israelis would just apologize for leaving Europe.” Leaving aside the fact that more than half of Israel’s Jewish population consists of Mizrahi Jews from the Middle East, I personally responded to ask the poster where else European Jews might have gone. The answer was that it was “better they be murdered than immigrate to an already populated area and intrude on the native population.”

Then there was the post that asked, “Since when is being Jewish socially acceptable?” In the comments, the author expounded on their opinions: “Why do we tolerate people being Jewish? It’s a choice, and it’s the wrong one.” The anonymous poster eventually explained the reasoning behind their hateful, anti-Semitic beliefs: “I’m pro-Palestine, that is all.”

It is no coincidence that many of these Yik Yak posts sprung up on campuses that were facing active BDS campaigns. At Stanford’s divestment hearing, Jewish students explained that divestment made them feel unsafe, and that they had faced anti-Semitism at Stanford. A pro-BDS student told us to calm down. “It’s not like we’re going to draw a swastika, or anything,” he said glibly, to cheers from the audience. Jewish students’ claims of facing anti-Semitism are often ignored — or worse. I was told I was “crying wolf” by claiming that anti-Semitism still exists in America.

Two months later, a swastika was spray-painted on a Stanford fraternity house.

It is impossible to know if a Yik Yak post is coming from an actual student on the campus, or merely someone who is visiting or just lives nearby. And there is no publicly-available data on the demographics of the user base. Nevertheless, the vast majority of posts on college-related Yik Yak feeds tend to be very campus-specific. A quick glance at my Yik Yak feed at Stanford, for instance, contains posts referring to Stanford classes, Stanford professors, Stanford’s meal plan, Stanford-only rules (“quiet hours”), and Stanford study spots and dormitories. It is dominated by posts almost surely made by students.

And Yik Yak’s own marketing has predominantly targeted college campuses, with the app’s founders reaching out to student leaders at schools across the country and going on advertising tours to colleges. The app currently has users at 1,600 universities, with at least half of the student body using Yik Yak at each of those schools.

So while it’s impossible to say conclusively whether any given post was written by a student, it is the most likely option.

I don’t want Yik Yak to be banned on Stanford’s campus, as it has been elsewhere. The app has been used to say terrible, hurtful things — but it also provides students with support and light-hearted entertainment. Furthermore, ugly speech should not be censored; instead, it should be brought to light. Students will not stop holding anti-Semitic attitudes if Yik Yak is banned — they will merely stop sharing those opinions where other Stanford students can easily see them. “Banning or blocking Yik Yak is akin to getting rid of cellphones, email, snail mail, and any other type of communications platform,” wrote Eric Stoller, a blogger for Inside Higher Ed. “The tool is not the issue. It’s the stuff that resides inside of the minds of those who are posting threats and/or racist/sexist/homophobic yaks.”

One of the main issues confronting Jewish students who face anti-Semitism on college campuses is the lack of attention to their concerns. While I tried to bring to light some of the anti-Semitic Stanford Yaks, no one seemed to pay much notice. When Jewish students complain about being subject to anti-Semitism, we are told that Jews are wealthy and successful, so anti-Semitism is no longer a problem; that it’s only an issue in Europe; that threats are not serious or are “just jokes” and we need to move on; that other minority groups have it way worse. That is, assuming we are not flat-out ignored, or, as during the divestment debate at Stanford, ridiculed and laughed at for our concerns.

Rather than banning Yik Yak, we can use it as a tool to better understand and combat anti-Semitism. It took until a swastika showed up on a Stanford fraternity house for any response from the university. And even in a letter prompted by a symbol of the murder of six million Jews, the response failed to specifically mention anti-Semitism or the particular struggles Jewish students face.

“I am deeply troubled by the act of vandalism, including symbols of hate, that has marred our campus,” university president John Hennessy wrote. “The university will not tolerate hate crimes and this incident will be fully investigated, both by campus police and by the university under our Acts of Intolerance Protocol. This level of incivility has no place at Stanford. I ask everyone in the university community to stand together against intolerance and hate, and to affirm our commitment to a campus community where discourse is civil, where we value differences, and where every individual is respected.”

There was no mention of anti-Semitism or Jewish students in his message. Jewish students’ voices, and instances of anti-Semitism in general, face erasure — from other students, from media, and even from the highest university officials.

To challenge this, we should use Yik Yak as a tool to illustrate the extent of anti-Semitic sentiment on college campuses. Posts on Yik Yak may serve as evidence to make sure anti-Semitism is acknowledged and treated seriously.

We ought not to seek to censor speech, but rather to speak out against hatred.

Miriam Pollock is a senior at Stanford University and a 2014 Tower Tomorrow Fellow. If you have seen anti-Semitic posts on Yik Yak, please send screenshots to editor@thetower.org.