Shimon Peres, the Nobel Prize-winning former Prime Minister and President of Israel, died Wednesday morning local time at the age of 93. He entered the hospital September 13 after suffering a hemorrhagic stroke.

The last of Israel’s living political leaders who had been involved in the founding of the Jewish state, Peres was instrumental in shaping Israel’s politics, and particularly its defense and foreign affairs, for nearly 70 years. Peres will be remembered for his decisive contributions to Israel’s defense and strategic capabilities in the state’s first three decades, his economic leadership during the country’s most acute crisis in the 1980s, his controversial and dramatic attempts at achieving peace in the 1990s, and, as President, his restoration of the institution of the presidency in the 2000s. He served as a top aide to Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, a cabinet member for Golda Meir, a bitter rival-turned-political ally of Yitzhak Rabin, and a surprising supporter of Ariel Sharon.

Peres also served as Prime Minister three times, for a total of nearly three years—two months in 1977 following the resignation of Yitzhak Rabin, two years in the 1980s as part of a power-sharing agreement with the Likud’s Yitzhak Shamir, and seven months following the assassination of Rabin in 1995. Peres, Rabin, and Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize the previous year for their roles in negotiating the Oslo Accords. After Rabin’s death, Peres was unable to complete his vision of a “New Middle East”—the title of his most famous book—in which an Israel at peace with a Palestinian state would forge economic partnerships with Arab countries. After a wave of Palestinian terror attacks, which much of the Israeli public believed Arafat to have directed but blamed Peres for failing to have stopped, the prime minister lost the subsequent Knesset election to Benjamin Netanyahu. Nonetheless, he continued to play an important role in Israeli politics, joining with Ariel Sharon to create the Kadima party in 2005 and culminating in his 2007-14 tenure as Israel’s president.

Peres was born Szymon Perski on August 2, 1923 in Vishnyeva, a town in what is now Belarus. He was the son of Yitzhak, a wealthy merchant, and Sara, a librarian. At the age of four, Yitzhak took him to visit Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan (the writer of the seminal book of ethics Chofetz Chaim), who gave him a blessing. Yitzhak immigrated to Tel Aviv in 1932, with the rest of his family joining two years later. While some family members had already left Europe by that point (including the grandfather of movie legend Lauren Bacall), most who remained in the town were killed in the Holocaust.

Peres was active in Labor Zionism from an early age, working on kibbutzim and leading youth groups, where he caught the eye of Ben-Gurion, the leader of the pre-state Yishuv government-in-waiting. In 1945, Peres married Sonya Gelman, with whom he would have three children. Sonya died in 2011.

Ben-Gurion made Peres his protégé, choosing him and Moshe Dayan to serve as delegates for the 1946 World Zionist Congress. The following year, Ben-Gurion made Peres responsible for all arms purchases for the Haganah, the pre-state Jewish military. In this role, Peres coordinated the sales—and in some cases, the smuggling—of weapons from all over the world to help prepare the Haganah for what all knew would be a bloody and difficult war for statehood. Peres proved to be a highly effective manager during Israel’s War of Independence, and quickly rose up the ranks in the military sphere. In 1953, Prime Minister Ben-Gurion appointed him Director-General of the Defense Ministry. He was 29 years old.

Shimon Peres, Director-General of the Israeli Defense Ministry at the age of 29. Photo credit: Government Press Office

Peres’ creativity and negotiation skills helped transform the Israel Defense Forces from ragtag refugees with cast-off and often faulty equipment into an elite military force with state-of-the-art supplies. He did this despite continued arms embargoes on the country by, for example, purchasing parts of fighter planes piece-by-piece, assembling them in rural California, and then having volunteer pilots fly them to Israel via the North Pole to avoid detection. Nearly single-handedly, Peres engineered Israel’s first military partnership with a major power by forging close personal and professional ties with political and military elites in France. Israel needed better weaponry to dissuade an increasingly belligerent Egypt from invading again; France, still recovering economically from World War II, needed cash, as well as intelligence to help quell the revolution in Algeria. The partnership, which was forged in the 1956 Suez Crisis, grew so close that Peres was able to persuade the French to help build Israel’s domestic nuclear program in Dimona. The initiative was to have profound consequences for the future of the country. “Dimona helped us to achieve Oslo,” Peres told Time in February. “Because many Arabs, out of suspicion, came to the conclusion that it’s very hard to destroy Israel because of it, because of their suspicion. Well, if the result is Dimona, I think I was right.”

Peres was elected to the Knesset in 1959 as part of Ben-Gurion’s Mapai party (the predecessor to today’s Labor Party). Ben-Gurion appointed him Deputy Defense Minister, one of many cabinet positions he served in 48 years in parliament (among the others: Minister of Immigrant Absorption, Minister of Transport and Communications, Minister of Information, Defense Minister, Finance Minister, and Foreign Minister).

Peres was never entirely able to escape his reputation as a wheeler-dealer; compared to Rabin, the war hero who was his decades-long rival for Labor Party leadership following Golda Meir’s retirement, Peres was perceived by the public to be an elitist bureaucrat. His strategic acumen was usually a boon: As Prime Minister from 1984-1986, he led the “Economic Stabilization Plan” that saved the country’s economy and lowered inflation from 450 percent to 14 percent. But his implacable optimism, desire for peace, and steadfast belief in his own negotiating skills nearly torpedoed his political career multiple times—such as a failed House of Cards-esque maneuver in 1990 that would have toppled the governing coalition in favor a smaller, more dovish one that he would lead, a move that was dubbed “the stinking trick.”

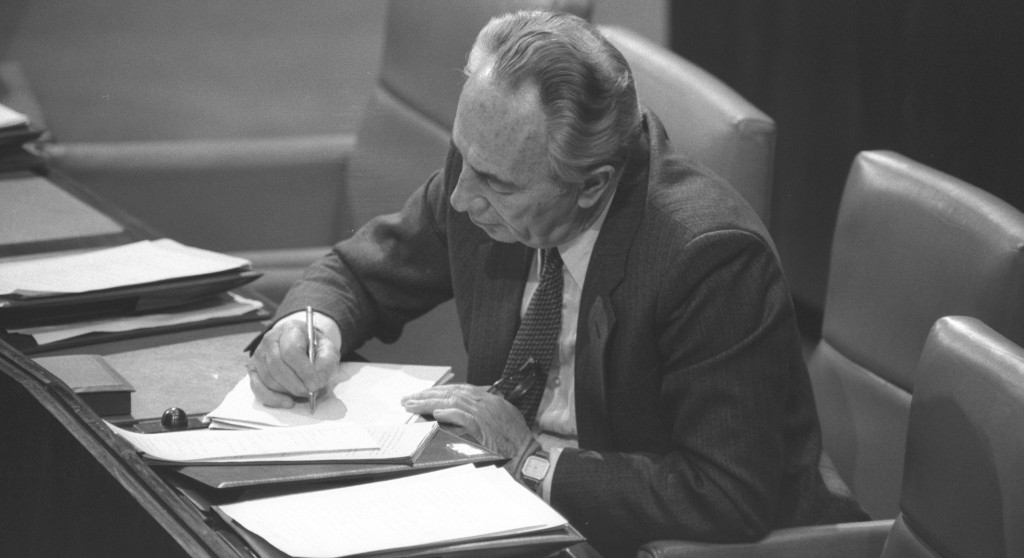

Prime Minister Shimon Peres takes notes in his seat in the Knesset, 1986. Photo: Nati Harnik / Government Press Office

As foreign minister to Rabin, who retook control of Labor in 1992, Peres was the official supervisor of secret negotiations with the PLO, which ultimately culminated in the Oslo Accords and a Nobel Prize. But after Peres assumed the premiership following Rabin’s assassination in November 1995, Israelis began to sour on continued negotiations with Arafat, who was widely seen as responsible for the rise of suicide bombings and other terror attacks. The May 1996 election was the first time that the prime minister was elected directly (a system that has since been cancelled). Netanyahu upset the favored Peres 50.5% to 49.5%. Peres actually led in the first reported exit polls, spawning the phrase that the country “went to sleep with Peres and woke up with Netanyahu.”

Though still a member of the Knesset, Peres was replaced as Labor leader by Ehud Barak and essentially cast into the political wilderness. But after Arafat walked away from peace negotiations with Barak and U.S. President Bill Clinton, the beginning of a series of events that culminated in the Second Intifada and the election of Ariel Sharon, Peres in 2001 once again became Foreign Minister as part of a Labor-Likud unity government—at the age of 78. He helped Labor support Sharon’s Gaza disengagement plan, before leaving the party in 2005 to serve as the deputy leader in Sharon’s new Kadima party.

In 2007, Peres completed his final political reinvention when the Knesset appointed him as Israel’s ninth president. The largely ceremonial office of the president was tarnished after the previous officeholder, Moshe Katzav, resigned after being accused of rape, sexual harassment, and obstruction of justice (crimes for which he was eventually convicted). Peres, from the ages of 84 to 90, reinvigorated the position, strengthening Israel’s image abroad while working on Israeli-Palestinian peace and cooperation initiatives through the government and through his foundation, the Peres Center for Peace.

President Barack Obama welcomes Israeli President Shimon Peres in the Oval Office, May 2009. Photo: Pete Souza / White House

When his term expired in 2014, Peres promised to maintain his presence on the political stage. He remained active through the Peres Center, on the internet, and at international conferences and ceremonies, where he received the Congressional Gold Medal and the French legion d’honneur, among other prizes.

“I will not give up my right to serve my people and my country,” he said in his July 2014 farewell speech, which took place during the third war between Israel and Hamas in seven years. “And I will continue to help build my country, with a deep belief that one day it will know peace.”

[Cover photo: Hadas Parush / Flash90]