Would a Palestinian state spark the fire that forges a united Middle East, or sets it ablaze?

If a state of Palestine were given independence tomorrow, would it become a failed state? Considering the international community’s conviction that Palestinian statehood holds the keys to a peaceful and prosperous Middle East, one would hope this nightmare scenario would be far-fetched. But a close examination reveals that this is wishful thinking. The truth is that, upon its birth, a state of Palestine would rank among the most fragile states in the world. And far from contributing to Middle East peace, the emergence of a new fragile state in a splintering region would result in increased conflict and instability, with potentially devastating consequences for its people, neighbors, and the international order.

Israelis, certainly, fear that a Palestinian state’s inherent fragility would threaten regional security. When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu says he is prepared to accept a Palestinian “state minus,” he is speaking for most of the Israeli public, which is loath to relinquish security control over the strategic highlands of the West Bank. The opposition party now leading in the polls, the centrist Yesh Atid, is talking about separation from the Palestinians over 15-20 years with the IDF retaining full freedom of maneuver. Isaac Herzog, head of the largest left-wing party, the Zionist Union, proposes the postponement of final-status talks by 10 years in hopes that a decade of non-violence and “dramatically accelerated” economic development will lay the groundwork for a sustainable peace.

And despite its frequent protestations otherwise, the international community also has misgivings about the Palestinians’ readiness for statehood, investing heavily in state-building projects in a tacit admission that the basis for a state does not yet exist. The mandate of the United Nations Development Assistance Framework for Palestine is to “build the social, economic and institutional basis for the Palestinian state.” Likewise, the mandate of the Quartet—composed of the U.S., the UN, the EU, and Russia—is to “help the Palestinians as they build the institutions and economy of a viable Palestinian state.” The international community tends to blame the Israeli occupation for the Palestinians’ lack of preparedness for statehood, and Israel shares some of the blame. But the problem remains.

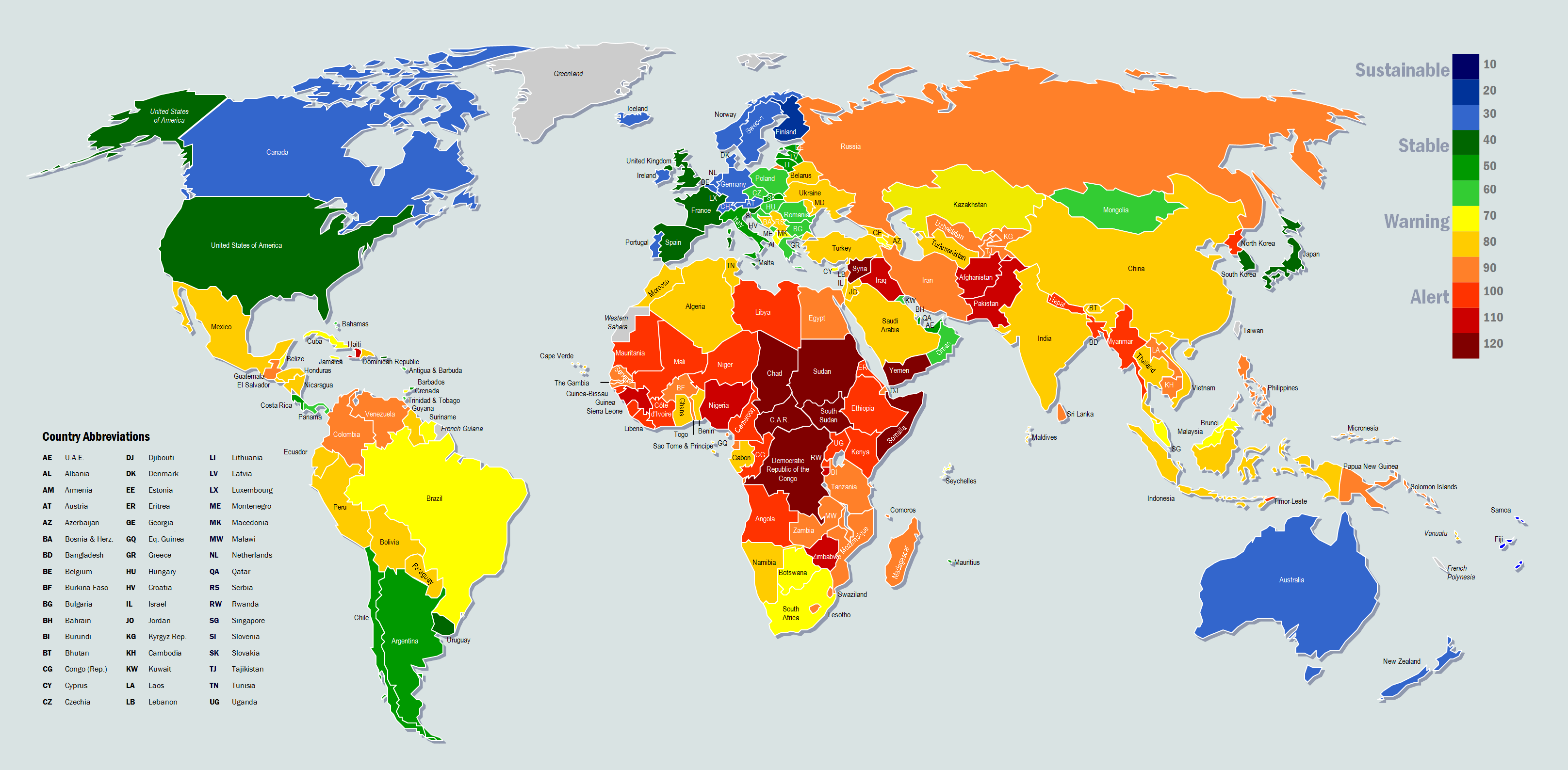

The reasons for state failure, according to the Fund for Peace, are complex but not unpredictable. In its annual Fragile States Index, the research institute assesses countries’ stability according to specific economic, social, and political criteria, and ranks how severely their very existence is threatened by such pressures. In 2016, Somalia was deemed most at risk, while Finland was crowned the world’s most sustainable state. The Palestinian territories are not analyzed. Rather, Israel is assessed together with the West Bank, and this single unit was most recently given an “elevated warning.” Since the study uses software to make its assessment, one cannot determine how this specific evaluation was reached.

However, if one applies the Fund for Peace’s methodology, it seems clear that a Palestinian state in the West Bank would likely receive a “high alert,” facing some of the world’s most serious challenges to its viability. This method takes 12 “conflict risk indicators” and ranks countries from 1-10 on each. A score of 10 means maximum vulnerability. Clearly, a Palestinian state’s stability would depend on the manner of Israel’s disengagement, so we’ll go with the best case scenario and assume a bilateral peace treaty has been signed followed by a prompt Israeli military and civilian withdrawal from the entire West Bank.

The stability of a future Palestine would also depend on whether it includes the Gaza Strip. Given that the addition of Gaza makes a future scenario even worse, let’s assess only the West Bank. All of the data used below comes either from the Palestinian Authority itself, NGOs, or international organizations, chiefly the UN and the Quartet. Readers are invited to run their own simulations and reach their own conclusions.

On day one of independence, Palestine would face considerable demographic pressures (#1). With 2.94 million residents (PA figures) over 5,640 square kilometers, Palestine’s population density of 519 people per square kilometer would make it the 23rd most densely populated country in the world—without outgoing Israeli settlers or incoming Palestinian refugees. It would be behind only the Gaza Strip and Lebanon in the Arab world. The West Bank is also experiencing one of the largest “youth bulges” outside of Africa: 40 percent of the West Bank and Gaza population is under the age of 15, second only to Iraq in the region. Unemployment is at 18 percent, on par with Yemen. Demographic pressures are particularly acute in certain areas: the Balata Refugee Camp, for example, is home to 30,000 people on just 0.25 square kilometers, with a 50 percent unemployment rate. This is evidence of what the Fund for Peace describes as “large-scale demographic pressures seriously affecting thousands of people.” On this issue, let’s give a future state of Palestine an 8.1, the same as Iraq.

These demographic pressures would be aggravated by a heavy influx of refugees (#2). It is clear that a state of Palestine would immediately grant automatic citizenship to over three million registered refugees in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. Most want to immigrate to a Palestinian state, joining the 775,000 refugees already in the West Bank, a quarter of whom live in camps run by the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). With no native resources to handle an influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees, Palestine would rank 9.3 on the risk list, on par with Jordan.

Palestine’s group grievances (#3) would remain high enough to threaten the viability of any new state. A West Bank state of Palestine would be born with a rival government in Gaza claiming to legitimately represent the Palestinian people. Hamas, which rules the Strip, is unlikely to accept a peace deal with Israel: its new hardline leader has just vowed to continue the conflict until “the liberation of all of Palestine.” Hamas would also likely have the sympathy of most of the Palestinian people: a recent poll shows 68 percent of West Bankers believe a one-state solution or the “reclaiming all of historic Palestine from the river to the sea” should be the “main Palestinian national goal.” Hamas’ rival Fatah, which rules the PA, is itself torn by rivalries, with gangs of gunmen loyal to different leaders frequently clashing with police in refugee camps.

A West Bank state of Palestine would be born with a rival government in Gaza claiming to legitimately represent the Palestinian people.

There are also numerous Islamist militias, which would reject a peace deal and continue to vigorously resist being disarmed, this time without the IDF on the ground to help do so. Palestine would get at least the same score the Fund for Peace gives Israel and the West Bank today: 9.8.

Regarding human flight and brain drain (#4), this would be greatly affected by whether Palestine becomes a failed state or not. Should an Israeli withdrawal prompt greater violence and unrest, the best and brightest of Palestinian society could emigrate, as many did during the second intifada. Alternatively, Palestine could serve as a magnet for an idealistic diaspora coming home from the first world. Giving it the benefit of the doubt, it would score no better or worse than Israel now: 3.5.

Compounding these social pressures would be economic burdens, chiefly uneven economic development (#5). The UN reports “great internal disparities” in per capita GDP in the West Bank. Much urban growth is unplanned and uncontrolled, affordable housing is “scarce”—partly because developers focus on high-end developments, and because the Oslo map does not let Palestinian localities expand—and overcrowding is high. One million West Bankers “need some form of humanitarian assistance.” Since the PA was established, Palestinians have received the second-largest sum of foreign aid in the world, and depend on growing remittances to neutralize the impact of shrinking international support. Some 200,000 refugees live in 19 sprawling but densely populated refugee camps. The prevalence of economically motivated anti-government violence in lawless refugee camps would mean, per the Fund for Peace framework, that “uneven economic development is somewhat severe along group lines and associated violence or displays of group grievance is sporadic.” On this issue, Palestine gets an 8.

It is impossible to predict what independence might do for the Palestinian economy. Gaining control over Area C in the West Bank, which is currently under full Israeli authority, and the lifting of restrictions on movement could unlock vast opportunities and encourage investment. But a state of Palestine would be established in a situation of economic decline (#6). According to the UN, the PA economy is “based on a weak foundation,” while the Quartet states that the West Bank lacks the “necessary infrastructure for growth and investment.” The PA’s GDP per capita is among the lowest in the Arab world, and real GDP growth last year was 2.7 percent, which the World Bank describes as “sluggish.” Moreover, with investment below the rate of depreciation, the PA’s capital base is shrinking, meaning “Palestinian GDP and employment, already insufficient, is likely to decrease.” At the moment, the PA economy is fueled by public expenditure, mainly civil service salaries, which the Quartet calls “unsustainable.” It says the same about the PA’s significant trade imbalance. With a weak economy facing decline, Palestine would score around a 7.

On the issue of political pressures, a state of Palestine would face its gravest problems. First, it would be born with serious challenges to its state legitimacy (#7). The PA is alienated from its people and endemically corrupt. Mahmoud Abbas is in the 13th year of a four-year term, and most Palestinians want him to resign. Parliamentary elections have not been held in over a decade. Last year, Palestinian courts suspended local elections. In his farewell Security Council briefing, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon warned that “the failure to organize Palestinian general elections has remained one of the clearest signs of … the fragile Palestinian democratic process.” He urged fresh elections to “renew” the “democratic legitimacy of the Palestinian leadership and institutions.”

Moreover, without reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas, two parties would claim to be the legitimate government of a Palestinian state. The irredentist Hamas, which leads in presidential polls, has armed militias in the West Bank ready to challenge any Fatah government. UN Special Coordinator Nickolay Mladenov reported last year, “We are nowhere near … genuine Palestinian unity on the basis of non-violence [and] democracy,” which he called “a crucial building block for the foundation of a Palestinian state.” With the government considered completely illegitimate and even criminal, endemic corruption, and the presence of a violent national opposition, Palestine would score a 9.5.

A member of Hamas’ al-Qassam Brigades takes part in a military parade in the southern Gaza Strip. Photo: Abed Rahim Khatib / Flash90

Any state of Palestine would be established with a serious lack of public services (#8). The Quartet notes, “There remain serious institutional, legal, and physical access impediments along the path to becoming an effective government.” The UN Special Coordinator reports a “massive deficit in infrastructure, including energy, water, waste, communications, and transport systems.” The PA has only recently secured control over its own electricity distribution and postal service. Palestinian cellular companies still cannot provide 3G services. There is no airport or railroad services in the West Bank.

As for the services that do exist, a state of Palestine would be dependent on the UN. Every day in the West Bank and Gaza, the UN, not the PA, provides free education to over 300,000 students and health services to almost 1.7 million patients. Every month it delivers 780,000 liters of fuel to sustain basic health, sanitation, and municipal services. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians continue to depend on basic food assistance. Palestine would get a 7.8 on this issue, on par with Iraq.

On human rights and the rule of law (#9), a state of Palestine would be severely compromised. Mladenov reports, “Many of the fundamental pre-conditions for rule of law development have yet to be realized. Fractured jurisdictions, the dysfunctional legislative environment, national institutional division, weak institutional capacities, and a lack of clarity around institutional roles and mandates are all key factors inhibiting rule of law development in Palestine.”

As for a free press and civil society, Human Rights Watch reports the PA is “arresting, abusing, and criminally charging journalists and activists who express peaceful criticism of the authorities.” These measures include “harassment, intimidation, and physical abuse” of critics, such as torture, beatings, sleep deprivation, and hosing with hot and cold water. More “benign” forms of harassment included using the public prosecutor to charge journalists with “insulting a higher authority.” These crackdowns, HRW says, “have a chilling effect on public debate in the traditional news media.”

In Palestine, per the Fund for Peace’s criteria, human rights would be “systematically and violently abused” and “almost no civil society or open media” would exist. Freedom House ranks the West Bank and Gaza lower than Egypt on press freedom. Let’s give it Egypt’s score: 9.8

Palestinian police deployed during a February 2017 demonstration by Hizb-ut-Tahrir party supporters in Hebron. Photo: Wisam Hashlamoun / Flash90

A state of Palestine’s security apparatus (#10) would be seriously deficient. The Quartet reports that “overall governance of the security sector remains fragmented, opaque, and in many cases outside civilian control.” It is true that PA security forces have made great advances and security coordination with them is one of the main reasons that the West Bank has been kept relatively quiet. But Israel’s military control of Area C means Palestinian police have no access to 40 percent of roads in the West Bank, while “access to over 300,000 people has been prohibited or severely restricted.” That means pockets of lawlessness. As mentioned above, gangs of gunmen control refugee camps. Illegal weapons are widespread. Hamas and Islamic Jihad have their own guerrilla cells, and it is reasonable to expect that they would take advantage of an Israeli withdrawal in order to expand their control. The UN highlights the “illicit arms buildup and militant activity by Hamas” as feeding instability. As “private militias are challenging the state” and regular security forces bypass the state as well, Palestine gets a 9.

Palestine would also be born with deeply factionalized elites (#11). With no nationwide elections in a decade, and militias still loyal to their various leaders, Palestine would be close to the Fund for Peace’s worst-case description, in which “no political class or national leader exists that is acceptable to the majority of the population … leaders are divided into factionalized parties” and a “a dictatorial party takes over through force.” Palestine would score a 9.6, again on par with Iraq.

Finally, Palestine would be subject to major external intervention (#12). If Israel were to withdraw its forces from the Jordan Valley, an international peacekeeping presence would have to take its place to prevent weapons smuggling. Iran would continue funding Hamas, just as it has done with Hezbollah in Lebanon. Palestine’s demilitarization would need to be monitored (the U.S. proposes using drones). And even after a withdrawal, Israel could not allow Palestine to control its airspace or electromagnetic spectrum.

Security aside, every major international organization would continue working in the West Bank. They would have to, since hundreds of thousands of Palestinians still receive basic services from the state-within-a-state of UNRWA. The PA budget remains dependent on foreign aid from the World Bank. In 2016, the U.S. aid budget alone stood at $290 million through USAID. The UN still hosts donors’ conference twice a year through the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee to coordinate aid efforts. The Palestinian government’s dependence on foreign assistance for its own viability renders it supremely vulnerable to budget cuts in foreign capitals: foreign aid slumped by 30 percent last year alone. And despite political independence, Palestine would also remain dependent on trade with Israel and remittances from workers there. As a landlocked country, it would also be dependent on goods coming through Israeli ports, and on payments transferred through Israeli institutions. On the issue of external intervention, Palestine would get a 9.9, the same as Afghanistan.

Based on the Fund for Peace’s criteria, Palestine would receive a “high alert” with a score of 101.3—the world’s fifteenth most fragile state, ranked between Pakistan and Burundi.

The fact that Palestine would be a fragile state is not, in itself, a reason to oppose Palestinian statehood. When Israel itself was created in 1948, it was an extremely fragile state. The CIA didn’t think it would survive two years. It too had militias loyal to rival parties, tripled its population in just two years with a refugee influx, and was completely cash-strapped. Whatever the risks, the powerful arguments of self-determination and human rights may make them worth taking. The suggestion that nations should not receive independence until they achieve full development is an argument for colonialism. Moreover, the present situation is dangerous and unsustainable even without Palestinian statehood, and a “one-state solution” could prove still more volatile.

Nonetheless, the international community must take these ominous signs into account before confidently predicting that a Palestinian state would further international peace and security, and admonishing Israelis for expressing skepticism that it might not.

This underlines the paradox inherent in the international community’s policy on this issue: The world calls for Israel to negotiate the creation of a Palestinian state, but according to its own data and statements, the PA lacks the foundations for viable statehood. The UN warns, “The full socio-economic development of the [occupied Palestinian territory] … will only take place when there is an end to the occupation.” But the urgent need for such development is precisely why ending the occupation would be so dangerous. Israel cannot expect a fragile Palestine to bear these risks by itself. Given its small size and proximity to Israel, any destabilizing fallout would inevitably spill over into Israel and provoke renewed conflict.

If the international community wants Palestinian statehood to be a success, it should focus on investing in the foundations for a viable state, while urging the parties not to take any steps incompatible with the two-state vision. If Israel is serious about Palestinian statehood as an ultimate goal, it needs to demonstrate how rapid development can be achieved without a military withdrawal. Israel is not a passive spectator, but a key actor in shaping what a Palestinian state would look like. And if the Palestinians face the painful conclusion that Israel cannot allow itself to withdraw in the short run, and be given meaningful guarantees that the hope of statehood is not extinguished, they can cooperate in building these foundations, instead of postponing difficult decisions like refugee resettlement to a later date.

A Palestinian state needs transparent institutions, functioning infrastructure, the rehabilitation of refugees, the disarmament of militias, a sustainable economy, and robust human rights. The assessment that a state without these fundamentals risks endangering international peace and security does not require a fortune teller—only a political scientist.

The Fund for Peace Conflict Framework Assessment Manual is available online. Readers are encouraged to run their own simulations and report results.

![]()

Banner Photo: Amir Levy / Flash90