A careful examination of the assumptions behind the current protest movement leave little doubt as to its real goals: To undo Israeli sovereignty in the entire southern half of the country.

In late 2013, large and sometimes violent protests erupted among Israel’s Bedouin population. They were directed against what has come to be called the Prawer Plan, an extensive blueprint for the development of Israel’s southern Negev desert, which is home to most of Israel’s Bedouin citizens. Although the plan’s intention was to improve the economic and political lot of the Bedouin, its opponents saw it as a direct assault on their community; mainly because the plan called for the relocation of large numbers of Bedouin currently living in illegal settlements unrecognized by the Israeli government. Bedouin activists claim these lands legally belong to them as an indigenous people whose rights are being violated by the Israeli government. Because of the protests, the plan is now in political limbo, impossible to approve or implement.

The protests did not come out of the blue. In recent years, a small but very influential movement has taken shape that calls for granting various collective rights to the Negev Bedouin. Although the Bedouin have enjoyed individual civil rights and equal access to government services since the founding of the State of Israel, this movement wants something quite different, and its proponents have something far more sinister in mind. Its activists and their supporters in academia and various NGOs advocate for what they call the Bedouin’s historical collective rights; in particular, their right to own large sections of the Negev desert.

In this context, the central demand is the recognition of the Bedouin as the “indigenous” people of the Negev. Because the Bedouin are an indigenous people, they theory goes, the Israeli government must recognize their internal tribal laws, particularly those regarding Bedouin land ownership. Accordingly, the Bedouin must be granted their “ownership claims,” and it is morally and legally incumbent to do so.

The issue with those demands is that they claims have no relation to reality, and the motive of those making the demands has less to do with Bedouins than it does with the opportunity it provides to portray Israel negatively.

Nonetheless, such claims have dominated the public conversation on the issue in recent years, and some of them have served as the basis for the deliberation of government committees dealing with the subject, such as the Goldberg Commission and the report that led to the Prawer Plan. These developments illustrate the progress made by Bedouin activists in furthering their claims.

When one examines these claims and, in particular, the evidence behind them, however, one quickly finds that they are extremely problematic. Some of them lack historical and documentary evidence; others are simply incorrect; while still others seem disingenuous and clearly intended to serve political rather than moral or legal goals. In the end, very few of them can stand up to scrutiny.

As mentioned above, one of the most popular claims made by Bedouin activists is that the Bedouin are the indigenous people of the Negev desert, similar to the Native Americans or the Australian aboriginals. The Bedouin, it is claimed, have lived in the Negev since the dawn of human history, and are an essential part of its landscape. This idea is widely disseminated by anti-Israel organizations abroad, as well as radical groups within Israel itself. To them, the narrative of a “dispossessed indigenous people” is indispensable to their view of Israel as an illegitimate, racist state; and of Zionism as a form of oppressive settler colonialism.

The indigenousness of the Bedouin has also met with a certain amount of international success, gaining more or less official recognition from various UN institutions and the European Union. With the support of such movements, both have made declarations to the effect that the Israeli Bedouin deserve the defense of international laws regarding the rights of indigenous peoples. In July 2012, for example, the European Parliament called “for the protection of the Bedouin communities of the West Bank and in the Negev, and for their rights to be fully respected by the Israeli authorities, and condemns any violations (e.g. house demolitions, forced displacements, public service limitations),” as well as “the withdrawal of the Prawer Plan by the Israeli Government.”

Although few have questioned such declarations, the use of the term “indigenous” in regard to the Bedouin is highly misleading and problematic. In fact, the term itself is a vague and amorphous one; though it is widely used, it is not actually defined in international law. Its widely accepted informal meaning, however, generally refers to something like a group composed of the “original” inhabitants of a certain territory, who have lived in it since the dawn of human history, and exercised some form of sovereignty over it before the arrival of a larger colonial power. In addition, certain cultural phenomena are seen as “indigenous,” such as a collective connection to the land and self-recognition as a people or chosen group.

Knesset Member Mohammad Barakeh of the Hadash party tears the Prawer Plan during a plenum meeting in the Knesset, in Jerusalem, June 24, 2013. Arab Knesset members left the plenum Monday evening in protest. Photo: Flash90

Professor Ruth Kark of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, a leading expert on the subject, has done extensive research into the history of the Negev Bedouin, and concluded that the definition of them as “indigenous” is quite dubious. She and her colleagues, Havatzelet Yahel and Seth J. Frantzman, presented their findings in a 2012 paper, in which they wrote “most of [the Bedouin tribes] arrived fairly recently, during the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, from the deserts of Arabia, Transjordan, Sinai, and Egypt.” Although Bedouin tribes did reside in the area before then, the Ottoman Empire’s tax records from the 16th century show that the tribes then living in the Negev “are not those residing there today.”

Kark and her colleagues are supported by the pre-eminent expert of Bedouin culture Clinton Bailey, whose research on the issue is considered definitive by many scholars. His examination of the few available primary sources on the Bedouin in both Sinai and the Negev, as well as Bedouin oral tradition, revealed that sources dating as far back as the 13th and 14th centuries do not “establish a contemporary presence for the great majority of tribes… found in Sinai and the Negev in the early nineteenth century, and which were still there in the mid-twentieth.”

It is also worth pointing out that the records that do exist often describe warfare whose purpose was the seizure of territory by migrating or semi-nomadic Bedouin tribes. It is logical to presume that such violence would not have been necessary had the tribes been genuinely “indigenous”; since indigenous peoples, by definition, do not have to conquer the territory in which they live, as they have been there since the beginning of time.

The issue is further complicated when one considers other aspects of “indigenousness.” Generally speaking, for example, the Bedouin do not appear to have developed a particularly strong spiritual or religious connection to the land itself. In fact, their semi-nomadic culture tended to see permanent settlement and working the land as somewhat dishonorable. Although the Bedouin do tend to place great importance on the specific tribal lands they control, this does not appear to apply to a larger territory, or to be spiritual or religious in nature. In keeping with their Muslim faith, the Bedouin have a religious connection to the territory of the Arabian Peninsula and the city of Mecca in particular, not to the Negev desert.

It is also telling that the Bedouin themselves did not claim to be an indigenous people until quite recently. There does not appear to be any historical evidence of a strong indigenous consciousness among the Bedouin; and not a single Bedouin tribe outside of southern Israel has asked to be recognized as an indigenous people, despite substantial populations in Sinai, Jordan, and even northern Israel. It often seems, in fact, that the claims regarding the indigenousness of the Bedouin are mostly political in nature, intended to further larger and more ambitious goals.

Along with the claim of indigenousness comes the claim of “dispossession.” In order to present the Bedouin as a dispossessed people, activists and their supporters make several claims: That the Negev “belonged” to the Bedouin for centuries before the founding of Israel. That the historical rulers of the region—the Ottoman Empire and then the British Mandate—both recognized the Bedouin’s “traditional historic ownership” of the Negev. And that only Israel has chosen to ignore these legal obligations in order to dispossess the land’s indigenous population.

Western opposition to the Prawer Plan is often based on faulty assumptions and questionable historicity.

The evidence for these accusations is, to say the least, questionable. To take one example, it is often held that the Ottoman regime acknowledged the distribution of tribal lands in the Negev and even officially set their borders. This claim has become extremely popular among the various groups supporting Bedouin activism, and especially so on the internet. It is absolutely central to their theory that the Ottoman regime officially acknowledged a kind of political “autonomy” for the Bedouins, which was then destroyed by “dispossession” and “Zionist colonialism.”

The claim that the Ottomans granted official recognition to Bedouin ownership of the Negev was first made by the scholar Emanuel Marx in 1974. He supported his theory by citing a map drawn up by the Ottomans during the First World War. Following publication, Marx’s conclusions became essential to other researchers, quoted repeatedly by scholars who had not seen the map themselves or checked the evidence behind it.

It appears that the first scholar to undertake this task was Dr. Emir Galilee, who went so far as to speak to Marx himself. This proved revelatory, as Marx explained that, “This map was hanging on the wall in the office of the military governor of the Negev in the 1950s. But, in fact, he didn’t know the source of the map and its exact provenance, so it can’t be trusted as a source.” In light of this, Galilee concluded a recently published study by writing, “Conclusions on the issue of the extent of the Ottoman authorities’ involvement in setting the borders between individual tribes in the Negev are problematic.”

Other historical claims made by the Bedouin and their supporters have met with a similar fate. Perhaps the most prominent among them was actually evaluated in an Israeli court of law, in the context of a lengthy legal dispute regarding the unrecognized village of Al Araqeeb in the northern Negev.

The key scholar in the Al Araqeeb case, as on many issues relating to the Negev Bedouin, is Professor Oren Yiftachel of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Yiftachel is a well-known human rights activist and radical leftist, who coined the term “ethnocracy”—referring to an ethnic democracy—to describe the State of Israel. Yiftachel led a team of researchers working for the plaintiffs in the Al Araqeeb case, and when it was adjudicated in district court, they presented what has come to be known as the “Churchill Document.” According to Yiftachel, this document proved that “The ownership system in Beersheva, as it was set down by traditional law, was acknowledged by the British government.”

Labor MK Merav Michaeli, speaks at the Internal Affairs and Environment committee meeting in the Knesset, during a discussion regarding a bill regulating Bedouin settlements in the Negev. Photo: Hadas Parush / Flash90

But when it came time for the court to evaluate these findings, it became clear that this was far from the truth. First, Yiftachel’s research was shown to be disturbingly shoddy. The court found a series of errors, citations of irrelevant sources, and inaccurate references to the names of various books and scholars. Second, Yiftachel was ultimately forced to admit that he had not checked the source itself, but relied on quotations from other scholars.

Indeed, it was quickly discovered that the most important quote from the Churchill Document (the state’s attorney had to find it himself, due to Yiftachel’s incorrect references) did not say anything like what the plaintiffs had claimed. It simply said, “Colonial Secretary Churchill approves that which was promised to the sheiks in the area of Beersheva by the High Commissioner Herbert Samuel; that no harm will be done to the customs and special rights of the Bedouin tribes.”

It is clear enough even to the non-expert that this statement, described by Yiftachel as “significantly strengthening” his claims, does not deal in any way with a land “ownership system,” but with undefined tribal customs and traditions. Moreover, after his claim was rejected by the court, Yiftachal admitted that he had largely written it himself. “The quote exists,” he said, “only its form is slightly different.”

Our reading of the court record revealed further problems. Cross-checking almost 300 pages of documents showed that Yiftachel ultimately could not defend even the one source quoted in his statement, and that, for the most part, he relied on the research of other scholars without bothering to examine the relevant sources or maps himself. This resulted in several egregious errors. For example, an Arabic document Yiftachel claimed was a military authorization permitting a tribe to settle in a certain area proved to be “a summer planting survey.”

Many Bedouin “ownership claims” are contradictory, or based on little proof.

Having failed in district court, the plaintiffs turned to the Supreme Court. This time, they asked to present “a piece of evidence cardinal to the appeal,” which was, they claimed, discovered only after their defeat in district court. It was referred to as the “Tahun Document,” and was said to prove that the Zionist movement itself had officially recognized the Bedouin’s ownership of the Negev. The document—which is now widespread on the websites of Bedouin organizations—is a list prepared by the Jewish Agency. It includes a breakdown of various Negev properties along with the names of their Bedouin owners.

This was seemingly crushing evidence. It appeared to show that the institutions of the State of Israel had acknowledged Bedouin ownership over hundreds of thousands of dunams, contradicting the current government’s official stance. But when the state attorneys responded, the picture began to look very different. The documents were, to put it mildly, very far from clear-cut. The attorneys pointed out that they were, in fact, “a collection of papers whose numbering is inconsistent; there are gaps and skips… the first page of the collection is missing; it is undated; and it is unclear who wrote it and for what purpose. The document is not even signed.” As to the plaintiff’s interpretation of the evidence, “The document relates to properties in a general sense, without any mapping, symbols, or divisions,” and “seemingly indicates things that were said by various sheiks in regard to working the land and the percentage of land used for agriculture.”

It was, in other words, nothing more than a list drawn up by someone at the Jewish Agency, a “market survey” of certain Negev lands based on what the Bedouin community had told him about their owners and availability. It was, in short, an unofficial document whose purpose was to serve as the basis for more serious attempts to buy land. It was very far, in other words, from a formal government acknowledgement of the Bedouin’s legal ownership over the lands in question.

The presentation of the document in court also proved distinctly problematic. When they appealed to the Supreme Court, the plaintiffs emphasized that this new evidence was not in their possession during the district court proceedings and “was discovered by the researchers after the appeal was filed.” It had been discovered, they claimed, by following up on “vague references in Arabic books.”

The state attorneys checked this claim as well, and discovered that the document had been brought to light in an article published in April 2012, a month before the appeal was filed. The article, moreover, had been prepared for publication at least a year before. In addition, a simple Google search revealed that the document had been published online in 2011, and by none other than Dr. Thabet Abu-Ras, head of the southern branch of the Arab rights NGO Adalah, and a good friend of and collaborator with Yiftachel.

Another serious area of contention for Negev Bedouin activists is that of “ownership claims.” These are land claims filed with the Israeli Justice Ministry in regard to large sections of the Negev. The petitioners usually claim that these lands were illegitimately taken from their rightful owners, who possessed the property under the Ottoman Empire’s practice of long-term leases known as tapu, or tabu in Arabic. These claims have been filed in the context of a process begun by the Justice Ministry itself, with the goal of legally formalizing all claims to land ownership in the Negev. Such attempts have been made since the days of the Ottoman Empire, thus far without success.

Although they are referred to as “claims,” it should be noted that these petitions lack any formal legal standing. They are simply assertions of ownership filed with the Justice Ministry for further inquiry. No supporting evidence or documentation is required in order to file such a claim. Indeed, approximately 200 of these claims have been legally rejected in verdicts upheld by the Supreme Court.

Bedouin activists and their supporters usually do not dispute the fact that these claims lack legal standing and are not based on any legally acceptable evidence. This is not considered particularly relevant, however, since most of these activists—especially in the NGO world—reject the basic legitimacy of Israeli law as it applies to the Negev. This point of view was succinctly stated by Tabet Abu-Ras, who said, “We, the Arab citizens of the state, do not accept the legal doctrine of land issues in Israel.”

If this is the case, however, it is worth asking why the claims are being made at all. According to Bedouin activists, the reason is simple: The ownership claims—even though they are not legal in nature—reflect the traditional divisions of property followed by the Bedouin tribes from ancient times up to the establishment of the State of Israel. They hold that the Bedouin informally divided the Negev amongst themselves according to their own tribal laws.

It is important to emphasize the enormity and ambition of this claim. According to Bedouin activists and their supporters, the 800 dunams cited in the ownership claims are only the beginning of the story. They believe that the entire Negev desert belongs to the Bedouin. That is, everything from Kiryat Gat to Eilat, virtually the entirety of southern Israel and approximately half the country’s land mass, is the indigenous homeland of the Bedouin, to which they have an absolute and inalienable right of possession that must be acknowledged by the state.

In this context, it becomes clear that the struggle over ownership claims is only part of a larger struggle to negate—de facto or de jure—Israeli sovereignty over the Negev. Indeed, this process has already begun, and, as noted above, NGOs like the Negev Coexistence Forum have succeeded in persuading the United Nations and the European Union to adopt several resolutions in support of it.

It is therefore hugely important to be accurate about the facts in question. Our own research into the available documentation has revealed that the ownership claims filed thus far are, for the most part, deeply flawed if not outright false. In many cases, we found that claims have been made on lands that are officially listed in tabu records as state land. In many other cases, the land in question was actually bought by the Jewish National Fund before Israel was founded. In still other cases, several contradictory or overlapping claims have been made on the same area.

Our suspicions were initially aroused when we requested basic background information from the Justice Ministry. A spokesman told us, “When filing an ownership claim, the presentation of evidence and/or the testimony of witnesses is not required; only details on the source of the claimed right must be provided, without proving it.” The spokesman admitted that, because of this, there are “contradictory claims regarding the same lands and also different claims regarding plots whose borders overlap.”

How many such contradictory claims exist? How many overlapping claims have been registered? According to the Justice Ministry, “at this point, before the rights claims have been investigated and clarified,” no one knows.

In the process of our investigation, we found several documents that seem emblematic of the problem. One particularly striking case involves a man named Sager Salameh Al-Huzayyal, who sold 401 dunams located next to Kibbutz Shoval in 1934. At the time, the British Mandatory government had issued its notorious White Paper, which severely limited land purchases by Jews. In order to get around this discriminatory law, the Jewish National Fund often purchased land through local Arab intermediaries. This is precisely what occurred in the case of Sager Al-Huzayyal. During the War of Independence, however the intermediary in question fled the area and became an absentee landlord. The property was then listed as state-owned land in the name of the custodian of absentee property. In the 1970s, however, Sager Al-Huzayyal registered an ownership claim on the same land he had sold in 1934. Given that he had reason to expect monetary compensation if his claim were approved, one can hardly blame him for doing so, especially since he was not required to provide any legal evidence of ownership.

A very similar case occurred in regard to two other members of the Al-Huzayyal tribe, Salman and Munir. They also sold their land to a JNF intermediary in 1934. The intermediary again became an absentee landlord. These two plots, the first constituting 185 and the second 519 dunams, were then registered as state lands. In this case, it was Salman and Munir’s descendants who claimed the land their relatives had sold.

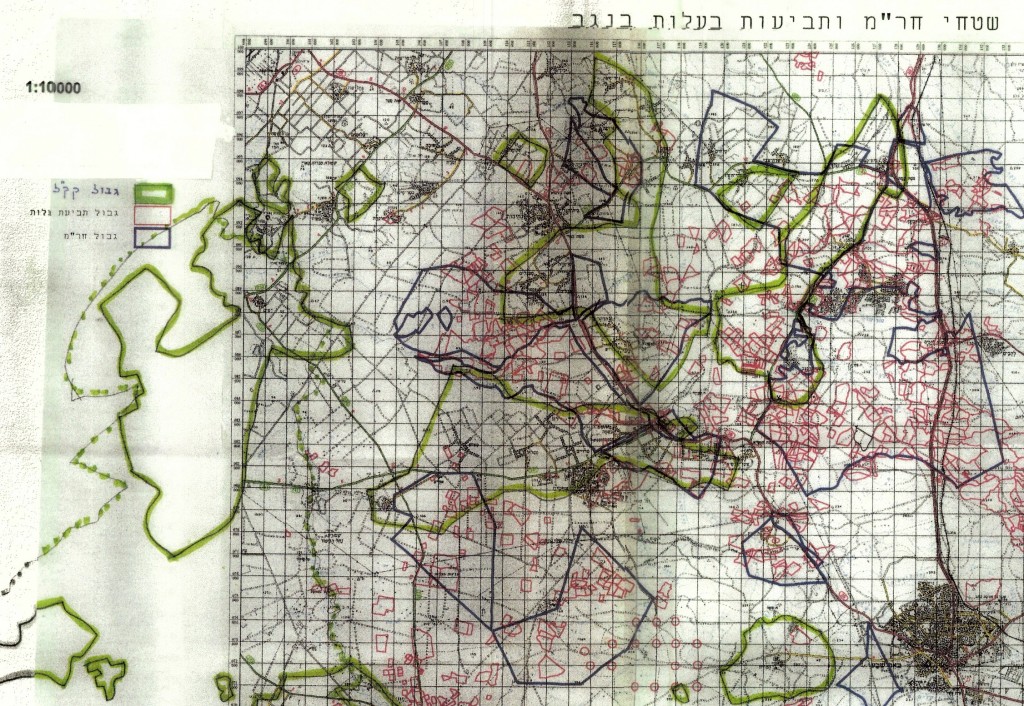

It is impossible to know, of course, just how many such claims exist amongst those that have been filed over the years. But one can get a sense of the size of the phenomenon by examining the map below. The Bedouin ownership claims are outlined in red, while lands bought by the JNF in the 1930s and ‘40s appear in green:

One can see quite easily that many of the ownership claims are located in JNF territories; approximately 30,000 dunams according to estimates. It seems likely that most of these areas came into JNF hands under precisely the same circumstances as mentioned above. Given the disorganized and scattered nature of the ownership claims, moreover, it is hard to see how they could represent ancient and organized tribal arrangements.

The Bedouin and their supporters have freedom of speech, of course, and are perfectly entitled to claim that they have an abstract right to own the entire Negev, which has belonged to them since the beginning of time. But at the very least, they ought to be honest about it, rather than attempting to obscure the issue through dubious legal tactics.

None of this is to say, of course, that the Negev Bedouin have no rights or that they do not deserve the civil rights they currently enjoy. Nor is it to imply that the State of Israel should not take steps to improve their economic and political situation. It is to say, instead, that such efforts must be based on historical reality and evidence, rather than demagogic claims, political radicalism, or emotional blackmail.

The evidence we have uncovered reveals that the claims made by radical Bedouin activists and their supporters are largely unfounded and insupportable. So far as can be ascertained, the Bedouin are not an indigenous people. They do not have any inherent right, official or unofficial, to the enormous territories they wish to claim, let alone the entirety of the Negev desert. Their attacks on Israel’s land laws are unfair and counterproductive. And these attacks are not moral or historic, but exclusively political in nature, designed to undermine Israel’s sovereignty and portray it negatively.

Saddest of all, however, is the fact that none of their activism will do anything to help the Bedouin community. It will only alienate them further from Israeli society, and mire them still deeper in their political and economic problems. Rather than make exaggerated claims that Israel cannot possibly fulfill, it would be better for those who have a genuine interest in helping the Bedouin people to work to improve the real situation and quality of life for Israel’s Bedouin. Collaboration in this project from Bedouin leaders and their supporters is the key to a better future for the Negev in general and the Bedouin in particular.

![]()

Banner Photo: David Buimovitch / Flash90