Shimon Peres was in the political arena for more than 60 years, and yet only won the country’s respect in his old age. But that wasn’t just a reflection of his longevity and experience—he earned it by remaining true to his principles, for better and for worse.

There is always something tragic about great men, particularly when they are the last of their generation. This was driven home for Israelis on September 28 with the death of Shimon Peres: former Israeli president, prime minister, foreign minister, defense minister, and practically everything else.

Like Moshe Dayan, Yitzhak Rabin, and Ariel Sharon before him, Peres seemed to personify both his era and his people. But where Dayan, Rabin, and Sharon personified the staunch soldier, the indefatigable sabra—hard-nosed, stoic, and security-minded—Peres seemed to be a throwback, a holdover, perhaps even an anachronistic remnant of diaspora Zionism’s earliest incarnation: the hopeful dreamer with visions that far outstripped the reality of the real world, and yet seemed somehow just within the realm of possibility.

And this was perhaps why Peres, for most of his career, seemed a somewhat disappointed, even tragic figure. His persona as a kind of apostle, a visionary entranced by the possibilities of the future, never quite captured the hearts of the Israeli people. He served for almost five decades in the Knesset and held almost every major government office, but his tenures at the top were always fleeting and controversial, and he found himself defeated at almost every turn, to the point where he earned the distasteful moniker “loser” from his detractors.

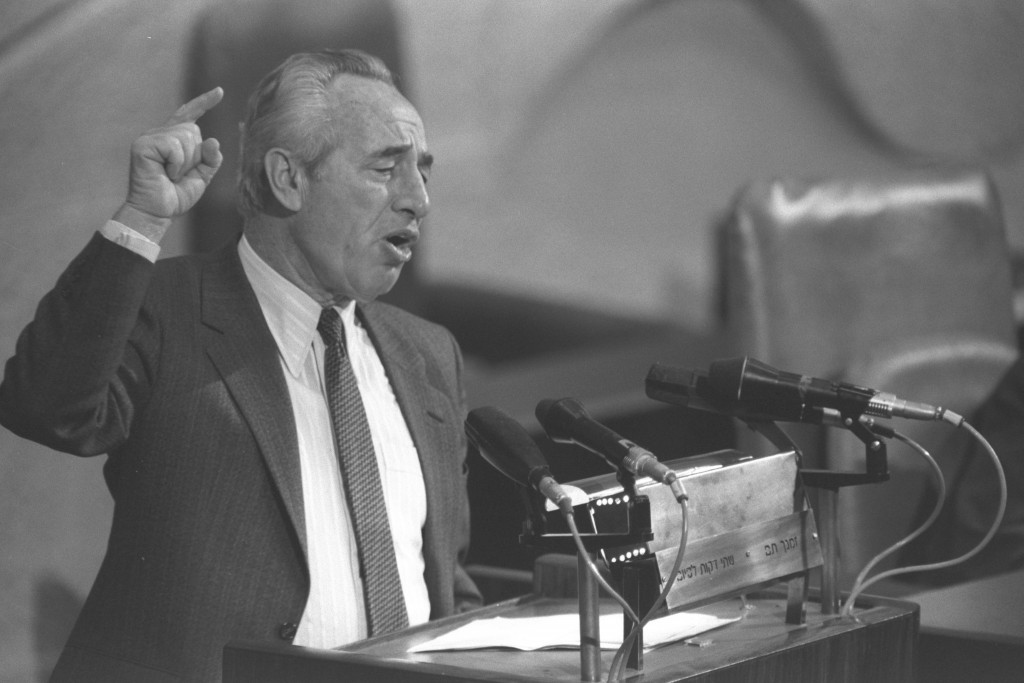

Prime Minister Shimon Peres replies to a no-confidence motion in the Knesset, February 3, 1986. Photo: Nati Harnik / Government Press Office

Yet he hung in there, stubbornly dedicated to his beliefs, bringing his considerable political talents for infighting to the perennial struggle for Israel’s survival, even as he saw his greatest endeavor—a “New Middle East” and the Oslo process he hoped would bring it about—collapse. He remained dedicated to the pursuit of new ideas, new technologies, and visions of peace.

In the end, it paid off. Often reviled even among members of his own Labor Party, when Peres became president in 2007 he succeeded, at long last, in becoming a consensus figure, admired by all as an adroit diplomat and spokesman for his country. He came to be seen as the last of his generation, a seemingly indestructible icon who, well into his 90s, maintained an energy and capacity for work that outstripped that of men a third of his age.

And in this, he became for many the personification of the country he loved and fought for all his life; because despite all the struggles, setbacks, disappointments, and defeats, his story was ultimately one of triumph.

Shimon Peres was born in Poland in 1923, and despite his lifelong secularism, had a remarkably religious upbringing, perhaps giving him his noticeably messianic worldview. This theological bent disappeared when he became a Zionist, and he and his family moved to then-Palestine in the early 1930s. He quickly became part of the Labor movement, which would be his home until 2005, and began what was in many ways a meteoric rise under the tutelage of Israel’s founding father David Ben-Gurion.

Contrary to his later dovish image, Peres distinguished himself early on in the military field, albeit not on the front lines. At the age of 29, he was appointed by Ben-Gurion as Director-General of the Ministry of Defense. Peres excelled in the backstage maneuvers necessary to keep Israel’s nascent military in a state of readiness.

In particular, he helped foster Israel’s earliest alliance with a major power. At a point when Israel’s close relationship with the United States was still some time away, Peres gained the military support of France, ultimately fostering the secret accord that, in collaboration with Britain, led to the Sinai War in 1956. While it proved an embarrassing defeat for France and Britain, Israel viewed it as a triumph, with the nascent IDF smashing through the Egyptian army, proving it could decisively defeat the Arab world’s strongest country despite the backing of the Soviet Union.

An image from 1958. Foreground, from left to right: Prime Minister’s Office director-general and future Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, IDF Chief of Staff and future defense and foreign minister Moshe Dayan, and Defense Ministry director-general and future prime minister and president Shimon Peres. Foreign minister and future prime minster Golda Meir is in the background. Photo: Fritz Cohen / Government Press Office

But perhaps Peres’ greatest early accomplishment was one that remains shrouded in mystery. It is, many believe, Peres who led the development of Israel’s nuclear facility in Dimona and its eventual acquisition of the ultimate weapon. While Israel continues to maintain “strategic ambiguity” on the issue, neither confirming nor denying its nuclear capability, there is now little question that Peres provided Israel with this last line of defense, ensuring the Jewish state’s military superiority and its most effective means of deterrence.

Peres entered the Knesset in 1959, where his rise was only slightly less meteoric. As deputy defense minister, he negotiated with John F. Kennedy to secure Israel’s first-ever defense deal with the United States, before quickly moving up the chain of government—from minister of immigration to transportation to information to defense.

When Yitzhak Rabin resigned after a corruption scandal, Peres capped his ascent by assuming leadership of Labor. It was, however, the beginning of a long and bitter rivalry with Rabin, with whom Peres’ destiny so often appeared unhappily intertwined.

Yet it was with his triumphant assumption of the party leadership that Peres’ winning streak ended. Under his tenure, Labor suffered its first electoral defeat in 1977, with Menachem Begin’s right-wing Likud party assuming power after 28 years of left-wing dominance. It was the beginning of Peres-as-loser, of his image as a partisan figure beloved in his own circles but unable to garner the support of the Israeli majority.

And it was Peres who, along with Begin, presided over an enduring split in Israeli society, exacerbated by the contentious struggle over the First Lebanon War. By this time, Peres had become Israel’s most prominent dove, and for Israelis dedicated to the center-Right, he was not just leader of the opposition, but a despised and hated rival.

This divide proved insoluble. In 1984, Labor and Likud essentially reached an electoral tie and Peres, bizarrely, became half a prime minister, serving in rotation with Likud leader Yitzhak Shamir. It was also during this time, however, that Peres marked another of his greatest, if less acknowledged accomplishments. With Israel’s economy collapsing and runaway inflation demolishing the country’s currency, it was Peres who fostered the liberal reforms that, slowly but surely, turned Israel from a socialist nation into a powerhouse of economic and technological innovation. It was a shift that Peres would champion until the end of his life.

Prime Minister Shimon Peres lights the cigarette of Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin, September 16, 1986. Photo: Moshe Shai / Flash90

During this time, however, Peres met with consistent failure in his efforts to lead Labor back to power, even resorting to Israel’s most notorious political maneuver—a secret plan to oust Shamir by forming a coalition with Israel’s religious parties. Rabin, now politically rehabilitated and gunning for Peres’ leadership role, named it “the stinking trick,” a phrase that etched itself forever into the Israeli political memory.

This was not the first time Rabin had slammed Peres in memorable fashion. At another point, he referred to his rival as an “inveterate schemer,” cementing, for many, Peres’ image in Israel as a Machiavellian politician. But considering how strongly that reputation stuck to him in the public consciousness, it’s almost striking to consider that despite his many bureaucratic and policy successes, most of his backroom political gambits failed to work—“the stinking trick” fell apart almost immediately, eventually leading to Rabin ousting Peres after 15 often-hapless years as Labor leader.

And yet it was precisely under Rabin’s leadership that Peres achieved his most storied success: The Oslo Accords. To Israelis, he remained controversial, but to the outside world, the accords made him an icon of peace, even as they began to fail.

Soon after Rabin led Labor to victory in 1992, secret contacts between Israelis and PLO officials began to bear fruit. As foreign minister, Peres took the lead in furthering these negotiations until Rabin, somewhat reluctantly, took them public, resulting in the signing of the Oslo Accords, a famous Rose Garden ceremony with President Bill Clinton, and ultimately a Nobel Peace Prize for Peres, Rabin, and Yasser Arafat.

At that moment, Peres seemed to be at his peak. Though still subordinate to Rabin, he was far more approachable than the taciturn prime minister, and the world was charmed. Peres became the icon of the Israeli Left, the king of the peace camp, his longtime dovish politics finally vindicated. His vision of a region economically, culturally, and diplomatically united by peace, set out in his book The New Middle East, seemed, for a moment, achievable.

Rabin’s assassination by a Jewish extremist opposed to the peace process made Peres head of government, but he proved again unable to retain power for long. In the face of a series of Palestinian suicide bombings, Peres steadily dropped in the polls until he was narrowly defeated by Benjamin Netanyahu.

At this point, Peres’ endless career did seem, at last, over. Even his status as an elder statesman seemed to desert him, as he lost a 2000 bid for Israel’s presidency to the now-incarcerated Moshe Katzav. But history had not had enough of Peres yet.

Prime Minister Ariel Sharon sits with Shimon Peres in the Knesset, January 2005. Photo: Sharon Perry / Flash90

When the Oslo Accords were destroyed by Arafat’s refusal of a peace agreement and the Palestinian atrocities of the second intifada, the Israeli peace camp and the Labor Party collapsed, ushering in the rule of the Left’s bête noir, Ariel Sharon. Most of Oslo’s architects saw their careers annihilated by Arafat’s perfidy, but Peres, somehow, proved once again indestructible. With a generation of its leaders now discredited, Labor turned back to its last surviving icon. Peres managed to assume the leadership twice more, leading the party into unity governments with Sharon and emerging, once again, as an eloquent spokesman for his country—asserting Israel’s desire for peace but refusing to engage in self-flagellation, offering a fervent defense of the Jewish state’s need for security and the actions necessary to achieve it. Peres gave Sharon critical backing for the 2005 withdrawal from Gaza and finally did the unthinkable, leaving Labor and joining forces with Sharon in the new Kadima party.

And strangely enough, it was at this time that non-left-wing Israelis slowly began to warm to Peres. The last remaining link to Israel’s founding generation, he began to transform into something like the nation’s grandfather. The change seemed cemented by something previously unprecedented: Peres, at long last, won. Gaining overwhelming support from his Knesset peers, Peres became Israel’s ninth president in 2007, assuming an office that, like so many, he had long sought but never quite achieved.

No longer Israel’s perennial “loser,” Peres’ term as president was triumphant. Israel’s presidency is intended to be a largely ceremonial office, meant to rise above petty politics and represent the entire nation to itself and the world. Against all previous indications, Peres did precisely this. He worked tirelessly at bipartisan endeavors to improve Israel’s standing both internally and externally, sponsored economic and technological innovation, spread his seemingly inexhaustible optimism, and served as the Jewish state’s de facto ambassador to the world.

Shimon Peres goes skydiving in a 2014 video after he retired from public office. Photo: Peres Spokesperson / Flash90

And in this, he also became something else: Israel’s one true optimist. Unlike the deeply realist Netanyahu, Peres made the impression of a man of faith, faith that the future would be better than the past and that Israel’s best days lie ahead. It is easy to dismiss such notions, but somehow, coming from a 90-year-old man who had been everywhere and seen everything over Israel’s first seven decades, it was convincing.

In the current cloud of grief, however, with a seemingly endless list of world leaders streaming to Mount Herzl to mark his passing, it is easy to forget that there were always two faces to Peres—one for Israel and one for the world.

To those outside the Jewish state, Peres was the ideal Israeli, a personification of hope and possibility, of the passions that made the desert bloom and resurrected an ancient nation.

Within Israel, however, Peres was always seen with a measure of ambivalence and controversy. To Mizrahi Jews, Peres was the personification of everything they resented and detested, one of the snobbish Ashkenazi elites who had unfairly dominated all facets of Israeli society for decades and seemed to view the Mizrahi community with little more than shallow contempt.

To the Israeli Right in general, Peres was both a ludicrous and vaguely dangerous figure. The Right has always viewed the Middle East through a lens of jaundiced pessimism, dedicated to Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s concept of the “iron wall,” according to which the Arab world would never consent to the existence of a Jewish state in their midst, leaving Israel to perpetually live by the sword and zealously guard its security by whatever means necessary. Given this, Peres’ sunny optimism, his belief in the possibilities of diplomacy and economic collaboration, and especially his “new Middle East” in which Israel would be not only at peace with the Arabs but live with them in perpetual friendship and harmony, seemed horrifically naïve—the concessions, especially territorial, required to realize that vision could fatally damage Israel’s security. At its extremes, the Right saw Peres as nothing less than a traitor. To this day, he is considered the worst of the “Oslo criminals” who supposedly sold Israel out to the PLO and ushered in an era of terrorism and death unprecedented in Israeli history.

Even on the Left, Peres had his detractors. Many were skeptical of his sweeping visions, his enthusiasm for politicking, and his refusal to cede leadership even in the face of multiple defeats. Ironically, considering their intertwined destinies, the strongest skeptic of them all was Rabin himself, who saw Peres as an unprincipled apparatchik whose “stinking trick” was the epitome of everything wrong with Israeli politics.

The truth is, Israeli society took a long time to love Shimon Peres. In some ways, this was simply an accident of talents. Israelis celebrate and tend to elect their military men, especially victorious generals like Rabin and Sharon; but Peres’ talent was for the bureaucratic, the administrative, and the subtle intricacies of diplomacy. It was, ironically, many of the qualities the outside world most adored—his smooth, charismatic charm; his eloquence; the ease with which he moved in elite circles; the way he seemed to wear his heart on his sleeve—that left Israelis, who tend to prefer their politicians rumpled and plain-spoken, often unimpressed. It was only at the end, when he could no longer directly influence policy; when he had been, in effect, neutralized; that his countrymen finally embraced him.

This embrace, however, was very real. And perhaps it came about because, in the end, Peres was very much the personification of the country that finally came to love him. He was, in many ways, a throwback to the ancient days of the state, to the Zionist founders like Herzl and Ben-Gurion. They were also men of great dreams, a belief in the future, and a firm vision of what Israel could and ought to become.

And like Herzl and Ben-Gurion, Peres was unafraid to test his dreams against the harsh realities of political life. Against the inevitable disappointments and disillusionments required to realize those dreams, whose reality is, inevitably, less than perfect. Nonetheless, like Israel and Zionism itself, he persevered, cognizant of the fact that, though it often appears otherwise, the world can be changed, and sometimes changed for the better, if one has the energy and faith to do so. In our world today, this sounds like a maudlin collection of clichés, but the life of Shimon Peres, like the life of Israel itself, proves that, if one is willing to sacrifice one’s most vital energies on their behalf, the loftiest ambitions can be realized.

Like his country, Peres faced innumerable setbacks, tragedies, and defeats. But he never stopped, never gave up, never allowed the world to crush his spirit. Like the saga of Israel itself, he reminded us that in this cynical world, there is still a place for dreams, for ideals, and for hope.

“It is not the critic who counts,” Theodore Roosevelt once wrote,

Not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

Like the great Zionists and founders of Israel, Shimon Peres dared greatly, strove valiantly, and came up short again and again. Yet he strove to do the deeds in service of his great enthusiasms and devotions, knowing throughout that he was spending himself in a worthy cause. And he knew the triumph of the highest achievements.

To be a Jew, a Zionist, and an Israeli, one cannot be one of the cold and timid souls. One will know both victory and defeat. If it teaches us anything, the life of Shimon Peres teaches us that, ultimately, it is all worth it.

![]()

Banner Photo: Yossi Zamir / Flash90