What happens when terror groups start recruiting the children of hard-working immigrants to the United States?

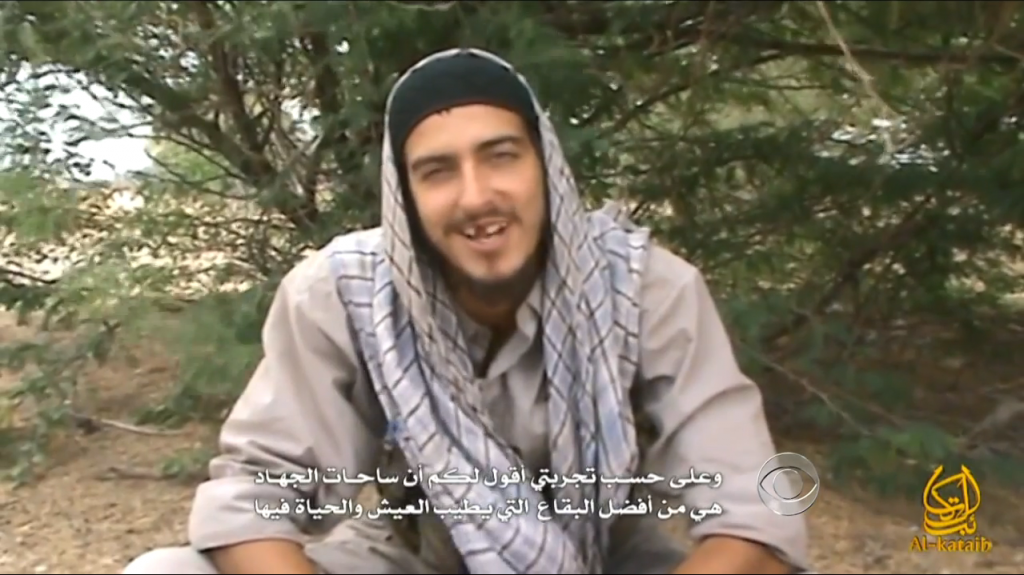

The soon-to-be-martyr, his wide smile showing a prominent gap where a front tooth used to be, his sleepy eyes glowing with the bliss of a righteous convert, sits in the shade of a tree somewhere in Somalia and makes his pitch:

This is the best place to be, honestly. I can only tell you from my experience being here that you have the best of dreams, you eat the best of food, and you’re with the best of the brothers and sisters, who came here for the sake of Allah. If you guys only knew how much fun we have over here! This is the real Disneyland! You need to come here and join us and take pleasure in this fun.

This is a recruitment video, intended to convince Somalis living overseas, often in America, to return to their homeland and join al-Shabab (literally, “the youth”), an Islamist militia the U.S. government has listed as a terrorist organization since 2008. These videos are fairly easy to find, if you know where and how to look. Some are in English, others in Somali or Arabic. Some are posted to YouTube and rack up a few thousand hits before someone flags them for violating Community Guidelines. Then they get deleted, but never really disappear. Instead, they are simply transferred to different file formats, posted on chat rooms, and downloaded onto an unknown number of laptops.

There is no question that these videos are the work of a skilled filmmaker, with flashy transitions and deft editing. Shots of terrorists firing RPGs and somersaulting with assault rifles are intercut with images of dead children from the early days of the Iraq War. Because musical instruments are forbidden in compliance with strict interpretation of sharia, or Islamic law, the imagery is underscored with catchy a capella singing and original rap songs extolling the glory of the cause: “Call on Allah and never retreat/Make our feet firm, Satan’s plan is weak/Islam is our faith, jihad is the peak/The best of our end’s to be a shahid.” The videos all have the same message: Come to Somalia, join al-Shabab, rid the land of unbelievers, and become a mujahid, a warrior for Islam; or better yet, a shahid, a martyr.

Troy Kastigar, a Minnesotan who converted to Islam, tells would-be recruits that Somalia is “the real Disneyland” in the infamous “Minnesota Martyrs” video. Photo: CBSNewsOnline / YouTube

The video, which surfaced in August but had probably been circulating for much longer, is different from the others, however. This one, a tribute to three fallen terrorists, specifically calls on Muslims in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, to join al-Shabab’s jihad to create a theocratic state in the Horn of Africa. Spliced between personal testimonials and images of urban warfare are shots of the Minneapolis skyline, the University of Minnesota campus, and the interior of the Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport.

Minnesota is home to the largest Somali community in the United States, and over the last six years, at least 22 Somali-American men have left the Twin Cities and joined al-Shabab, two of whom as recently as July 2012. These are only the confirmed cases; in fact, some community members say the number could be as high as 40. Dozens more from Minnesota and around the country have been indicted for providing material support to the terrorist group. Virtually all have been convicted. Many were inspired by recruitment videos like the one described above. Moreover, the FBI is “proceeding as if recruitment efforts are still occurring here in Minnesota,” according to Kyle Loven, a spokesman for the agency’s Minneapolis branch.

What would cause Somali-Americans to leave Minnesota—a state that has, for the most part, accepted them with open arms—to fight for a terrorist organization that heralds America’s destruction? And what can be done to reverse this worrying trend?

I flew back to Minneapolis, where I was raised, to try to answer these questions. While there, I discovered a few men who, amidst indifference and fear, have sacrificed their time and income in hopes of steering their community away from supporting terrorism.

The popular image of Minnesotans is found in Fargo and A Prairie Home Companion: Friendly Scandinavians who play pond hockey in blizzards, talk with funny accents, and elect wrestlers to public office. Comedian Chris Rock once joked that the only black people in Minnesota are Prince and Kirby Puckett.

Kirby Puckett has since died.

But this monochromatic perception ignores Minnesota’s rich history of providing a haven for refugees from around the world. Over the last 30 years, the State Department, the Minnesota Department of Human Services, and private charitable foundations (known as volunteer agencies or VOLAGs) have worked to establish the Twin Cities metro area as a hub for refugees from Iraq to Liberia to the former Soviet Union. The experience built up by these public-private partnerships, which began with the arrival of Saint Paul’s Hmong community in the late 1970s, made the state uniquely suited to absorb the massive influx of Somalis that began to enter the U.S. when their country’s ongoing civil war broke out in 1991.

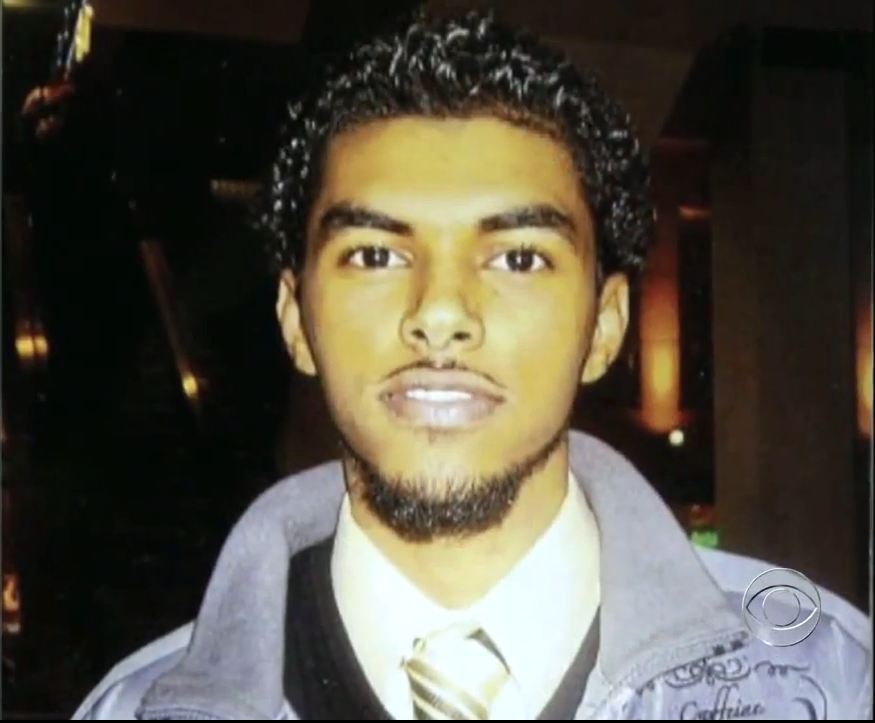

The last known photo of Jamal Bana, an engineering student who joined al-Shabab and died in Somalia. Photo: CBSNewsOnline / YouTube

Usually, the organizations involved attempt to settle refugees in places where their community already has a foothold in America. In 1991, the only Somali community to speak of was in San Diego, but local VOLAGs were eventually overwhelmed by a combination of the unexpectedly high number of refugees and California’s sluggish economy. As a result, they began to settle Somali refugees across the country. Then, on May 20, 1992, the Heartland Food Company placed a help-wanted ad in the Sioux Falls, South Dakota Argus Leader, seeking workers for a third shift at its turkey plant ninety miles away in Marshall, Minnesota. Four Somalis from Sioux Falls showed up the next day, were hired on the spot despite their minimal English, and were told to recommend the job to as many people as they knew. Word spread to San Diego, and over the next few months, dozens of families made the trek to Minnesota, attracted by the state’s high minimum wage, low unemployment, and cheap cost of living.

Minnesota’s economy boomed in the 1990s, growing twice as fast as its population. Over the course of the decade, Minnesota’s unemployment rate was well below the national average, falling as low as 2.8 percent in 1998. This, combined with the expertise of the state’s VOLAGs and the feeling among Somalis that “Minnesota Nice” people were very welcoming, made Minnesota an increasingly popular destination for Somali refugees. The local economy slowed in the first decade of the new century, but by that point, the Somali community had grown and matured, establishing stores, restaurants, and cultural programs.

As a result, Minnesota, and especially Minneapolis, became the place for Somalis to immigrate if they wanted to stay connected to their homeland. The most recent American Community Survey, completed in 2012, estimates that there are 32,000 Somalis in Minnesota. This number is almost certainly too low, due to residual suspicion of the government within the Somali community. Some community leaders believe the number may be as high as 100,000.

Despite Minnesota’s generous policies and the economic opportunities available, however, life is not easy for the local Somali population. More than 60 percent of Minnesota Somalis live below the poverty line. Unemployment stands at almost 21 percent, with a median age of 25, more than ten years below the state average. In the early years of the community, many Somali students had come from refugee camps and lacked any prior education or basic literacy skills. Unsurprisingly, they struggled academically.

Social life was a challenge as well. Somali schoolchildren were ostracized by African-American students for not being “black” enough, but also criticized by their parents and communal elders for acting too “ghetto.” The latter problem persists to this day, as community activist Abdirizak Bihi once demonstrated to his fellow leaders. “I would have Mohamed stand up,” he told me,

a young man, and ask elders to give their opinion [based on his appearance]. My God, it was the worst thing…. They called him all kinds of bad names. “Look at him. Look at his pants….” And Mohamed couldn’t understand what was wrong with them, and how bad things had become. They called him “gang, ungrateful, a waste of resources and time,” and many other names. After they were done, I announced who Mohamed was. “This is Mohamed Ahmed, a third year at Augsburg College in chemical engineering.” And when I explained that to them, they couldn’t believe it. Some even asked for ID.

Outward appearance, of course, is not the only difficulty Somalis have had in reconciling their traditions and American culture. In 2006, some Somali taxi drivers began asking passengers if they had alcohol in their bags. If they did, the drivers refused to take them, saying it was a violation of their faith. They also refused to admit passengers with dogs (including seeing-eye dogs), claiming they were “unclean.” An ordinance was eventually passed that revoked a cab driver’s license for 30 days if they refused to take a passenger for any reason. The Minnesota Court of Appeals upheld the law.

More troubling was a 2010 interfaith service held to reassure the Muslim community after Florida pastor Terry Jones threatened to burn a copy of the Koran. The event was marred when an imam referred to other Muslims who attended the service as “infidels” for praying inside a church.

But the biggest problem is, unquestionably, the fact that dozens of the community’s members have joined an internationally recognized terrorist organization, with many more convicted of aiding and abetting it.

For the most part, Minneapolis is a liberal, fair-minded, live-and-let-live kind of city. It was once named the gayest city in America, which is kind of ridiculous as long as San Francisco exists. But the fact that it’s at least plausible shows the degree to which the City of Lakes has accepted all sorts of outsiders. As you travel out to the Twin Cities’ endless exurbs, however, and into what is rather patronizingly referred to as Greater Minnesota, you increasingly see the flip side of Minnesota Nice: Passive-aggressive, good-fences-make-good-neighbors worshippers of the Law of Jante. Which doesn’t always make even the most peaceful Muslim immigrants feel especially welcome.

Minnesota’s eighth-largest city, St. Cloud, which has been described as having “long been an insular community closed to outsiders,” has seen “GO HOME” spray-painted on a halal grocery store and hundreds of petitions against the construction of a new mosque. Katherine Kersten spent nearly the entirety of her tenure as a Metro columnist for the Star Tribune fighting against the existence of Tarek ibn Ziyad Academy, a charter school in the Saint Paul suburb of Inver Grove Heights sponsored by Islamic Relief USA. The school was eventually shut down by the state, but the heavy media attention may have played a role in threats made against students and teachers.

In Minneapolis, the heart and soul of the Somali community is the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood, also known as the “West Bank.” Most Somalis in the area live in Riverside Plaza, a series of Brutalist concrete high-rises first opened in 1974. Riverside Plaza was an experimental complex, the first (and only) completed stage of a planned utopian development meant to revitalize the economically depressed neighborhood. It was designed to allow high-, middle-, and low-income residents, along with those on public assistance, to live side-by-side in harmony. The project never lived up to its potential. In the words of Paul Pink, one of the architects of the buildings (and my great-uncle), Riverside Plaza failed because “poor people want to live with rich people, but rich people don’t want to live with poor people.”

The state took over Riverside Plaza in the 1980s, and it is now Minnesota’s largest housing development, with more than 4,000 residents. Nearly 80 percent of them are East African. The project is depressingly dysfunctional, even after a recent $132 million renovation. For example, most of the buildings are 20 or more stories tall, but contain only two elevators, which are slow and frequently break down. The buildings are referred to by letter: B, C, D, F, and M. Remove the pastel siding and they wouldn’t look out of place in 1970s East Germany. Students at the University of Minnesota, four blocks and a million miles away, call them the “Crack Stacks” due to a legacy of rampant crime and drug addiction that the neighborhood is only now starting to overcome.

Some Somalis have begun advocating for change through traditional political institutions. Hussein Samatar served on the Minneapolis School Board for three years before dying of leukemia this August, and Abdi Warsame was just elected to the Minneapolis City Council. In true American fashion, the election campaign devolved into mutual recriminations and ballot shenanigans, but Warsame pulled through to a resounding victory in the end.

The most publicly visible Somali-American in Minneapolis, however, holds no official title. Abdirizak Bihi is the founder, director, and sole employee of the Somali Education and Social Advocacy Center. His mission consumes every waking moment of every day. There are too many unemployed, disaffected young men in Cedar-Riverside, and Bihi’s job is to get to them before al-Shabab does.

Abdirizak Bihi’s voicemail is always full. To get ahold of him, you have to call his cell, listen to the machine tell you that it can’t store any more messages, and then wait for him to call you back, which usually takes less than half an hour. I first talked to him a week after Kenya’s foreign minister told PBS she believed that Somali-Americans from Minnesota were involved in the September 21, 2013 massacre at Nairobi’s Westgate shopping mall.

Abdirizak Bihi checks his email and text messages outside Riverside Plaza. Photo: Aiden Pink / The Tower

“We had a lot of fear,” Bihi said. “That was my concern, because every time that fear surrounds us, it makes my work difficult, because the negative characterization and demonization of the community shuts off the community. And when the community shuts off, it’s very difficult for me to engage and for them to collaborate with law enforcement.” But since the claim had yet to be proven, he said, the mood in the Somali community was a “kind of celebration.”

Bihi came to the United States in the late 1980s, starting in Washington, DC, and eventually making his way to Minneapolis, where he found a job as an interpreter at a hospital. He saved enough money to bring his sister and nephew from a refugee camp in Kenya. The nephew, Burhan Hassan, acclimated quickly to American culture, obsessing over the NFL, getting good grades at Minneapolis’ Roosevelt High School, and dreaming of becoming a doctor.

In November 2008, Hassan vanished.

Bihi found videos of the extremist cleric Anwar al-Awlaki on Hassan’s laptop, which had been left behind. On June 5, 2009, Hassan was killed in Somalia. It was the same day he would have graduated high school.

His uncle has devoted the rest of his life to making sure that no Somali boy shares his nephew’s fate. He often feels alone in his struggle, relying solely on donations from Somali community leaders and businessmen. “No government, no other foundations, nothing. It’s frustrating.” The resulting inconsistent income has put a serious strain on his family. But Bihi presses on. He helps young men sign up for after-school tutoring. He drives them to probation hearings across the river in Saint Paul. He spends hours a day in his office, a tiny room in the back of a local community center, searching social media web sites for warning signs of radicalization. He is working with the Minnesota Vikings football team to make sure that the “minority quota” of construction jobs for their new stadium is filled with Somalis. Unfortunately, very few Somalis are actually in the construction business. So every Wednesday, he takes twelve young men to Summit Academy, a vocational training program in Saint Paul.

A few times a day, he goes out to take the “beat of the community,” catching up with everybody he meets on the street to see if they know anyone who needs guidance or support. He suggested I tag along for one of his tours. I agreed, not realizing how much of a workout I was going to get.

We started at his office, where he had just finished arranging for a young man named Ahmed to be tutored in math. I noticed that Bihi spoke to him in a mixture of English and Somali. “For the young generation it’s primarily English if you want them to understand well,” he says, walking much faster than I would have expected for a middle-aged, two-pack-a-day smoker. “They feel this sense of shame that they don’t know Somali. An elder of my generation might condemn them. Over the last five years, one of the worst things we have identified is the intergenerational gap and hostility. The majority of the community hasn’t recognized that it makes our young kids difficult, that we shame them.”

“It’s challenging, though,” I say, “because you still want to maintain a connection to your culture and history.”

“My daughters now want to learn Somali,” he replies, “because we didn’t rush them.” Bihi stops to greet two women who are passing by. “But when we condemn them or pressure them,” he continues, “they run away from me. They’ll never learn it. They’ll come to hate it, because you’re forcing them. One case in point—”

“Bihi!” a group of men yell after him. Bihi runs over to them and they shake hands. They quickly start talking in Somali. One of them bums a cigarette off Bihi. At the end, Bihi gives them all his cell phone number.

This proves to be a recurring pattern throughout the rest of my tour of Cedar-Riverside: We walk and talk about issues plaguing the community and Bihi’s strategies for fighting al-Shabab recruitment, while every few minutes, all sorts of people—young and old, male and female—call out to him and catch him up on what’s going on in their lives. Bihi introduces me to all of them (I think I met 11 or 12 “very important men”), then offers them a cigarette and his phone number. Sometimes they just tell him about their day. Bihi listens, commiserates, and gains their trust, hoping to make them comfortable enough to come to him if they become concerned about their relatives.

The hot story around town is a botched Navy SEAL raid in Somalia, which failed to capture its al-Shabab target. “They were brandishing American weapons on al-Shabab websites,” Bihi tells me. “So the word is already getting out in the community that al-Shabab is stronger and can defeat the U.S.”

I ask him what he tells people to watch out for as signs of potential radicalization. “You have kids,” he says,

young men that were active in school, playing basketball or hockey, have a lot of friends, working part-time, and suddenly they’re not doing any of this. Isolated, more religious, pensive, spending time away from parents in the mosque or some other place. That’s one of the big things to watch out for, is the behavior change. Second—

“Bihi!” calls a group of men coming out of a nearby grocery store. They shake his hand. They talk about the SEALs, about Westgate, and how they are relieved that no one from the community seems to have been involved. The conversation ends after an exchange of cigarettes and phone numbers, and Bihi is off in search of more people to talk to. The subject of our conversation changes quickly, never lasting too long before we are interrupted again.

Bihi worries about the recruitment videos, but is more concerned about structural and community-related problems.

You’ve got to have someone on the ground. For example, a single mom’s kid will have to have someone to become a mentor to teach him the good things, take him to the movies, be his dad. That’s what al-Shabab does. The recruiter becomes the father. We need to engage them. Basketball teams. The things we fail to do, constantly, because of lack of resources.

“Wait,” I ask, “al-Shabab recruiters have basketball teams?”

“They used to have them, in the past,” he replied. “They were good! That’s why we challenged them by having teams. We have to compete. They have resources, we have nothing.”

Bihi’s theory of terror recruitment starts to emerge. The structural difficulties that the Somali community faces—poverty, unemployment, discrimination—lead to disaffection, which pushes young men into the hands of radical Islam. But the lack of institutional support for counter-recruitment efforts like his makes the task of fighting radicalization that much harder.

At the same time, Bihi lays a lot of the blame on local elders and community leaders. One of his conversations on our walk was with a group of elders who talked about a nine-year-old who had recently snuck through the Minneapolis-Saint Paul airport security screening and onto a flight to Las Vegas. Afterwards, he laments the attitude of the older generation.

They said, “Nine years old? That’s amazing, what he did. But a Somali-American nine-year-old? They are idiots. A nine-year-old in Somalia used to be a camel herder, used to do this and that, very strong and smart.” The relationship between the first generation and the second generation is the worst. Elders think kids are ungrateful. They spent years in very bad refugee camps, praying to God that they will make it to America, because of the kids. But when they came here, look what they say about them: “They have the pants running here, they’re stupid, they don’t speak Somali, they’re dropping out of school.” But they never talk about why. They never support them.

By now, we’ve almost made a full loop around Cedar-Riverside, and Bihi is sweating noticeably. He sits down to take a breather, and almost immediately gets a call on his phone from a mother concerned that her recently-paroled son can’t find a job. He says he will pick him up on Wednesday at nine o’clock—“Not on Somali time, but American time”—and take him to Summit Academy for construction classes. “Sometimes I feel like my life is between a hard place and a rock,” he tells me after hanging up.

I ask him what he thinks of Minnesota. “Every one of us is grateful of Minnesota,” he says, “because I don’t think any other state could have done this. They have welcomed us, they have empowered us, up to a limit, to do things, and they continue to help us. The thing is, they don’t—”

“Daddy!” shouts a pair of young girls. Bihi’s daughters have come home from school and they immediately jump into his arms. I can’t tell if Bihi is pretending to be almost knocked over, or if he really doesn’t have much strength left. His daughters wear cute hijabs that match their shoes, and speak with the flat vowels of the Upper Midwest. They run toward the community center, where they attend an after-school program. “Wait, I have to take you there!” Bihi yells wearily.

Eventually, we make it to the community center, and after dropping off his daughters, Bihi returns to his office and sits at his computer, looking to see if he’s missed any news. His first stop is somalimidnimo.com, a pro-al-Shabab website based in Minneapolis that first garnered attention when it supported the anti-interfaith imam mentioned above. Most of the content is in Somali, which Bihi thinks is more informative when searching for news about his homeland, however skewed the reporting may be.

“I know the guy who runs this,” Bihi tells me. “His name is Abdiweli Dalbon. He’s a cab driver.”

“Wait. You know him?”

“Yeah, we look out for each other.” Bihi replies. (Dalbon did not reply to a request to be interviewed).

We talk a little bit longer about raising a family and the movie Captain Phillips. In his characteristic role as unofficial representative of the community, Bihi helped arrange publicity for the Minneapolis casting call that led to four community members winning roles as pirates. But soon he has to go to another appointment, and we say our goodbyes. I drive home and plop down on the couch, exhausted. I look at my watch and realize that I had been with Abdirizak Bihi for all of an hour and fifteen minutes.

The Somali diaspora is deeply connected to its homeland. Every year, Somalis living overseas wire more than $1.2 billion to family members back home. Most of these remittances come in small sums—$50 this month, $100 the next—but it adds up to more than double the amount of official Western aid. Numerous public access radio and TV shows, plus dozens of websites like Hiiraan Online and Somali Diaspora News, keep the community, which Bihi repeatedly described as “news junkies,” up to speed on the latest developments in the old country.

So al-Shabab’s growth in prominence after the December 2006 U.S.-supported Ethiopian invasion of Somalia was no surprise to the community. Rumors spread that the Ethiopians, who have a long history of occupying Somalia, had committed atrocities against civilians during their recapture of Mogadishu from the Islamic Court Union, a Taliban-like collection of Islamist groups. Al-Shabab was one of these groups, and it quickly began a campaign of terrorism and guerrilla warfare against the Ethiopians, the Somali Transitional Federal Government, and later the African Union peacekeeping force AMISOM.

The results have been horrifying and brutal. In 2011, during the worst drought in 60 years, al-Shabab refused to allow Western aid agencies into areas they controlled, fearing that the aid workers were spies or “luring needy people with food in order to teach them their Christianity.” Events like the attack on the Westgate mall and a suicide bombing at a World Cup viewing party in Uganda that killed 76 people were undertaken as both acts of revenge against participants in the AMISOM force and attacks on Western culture. Other atrocities, like the 2009 suicide bombing of Mogadishu’s Benadir University graduation ceremony, which killed three government ministers and 19 students, were intended to weaken al-Shabab’s opponents and consolidate its power.

This wide range of targets demonstrates al-Shabab’s dual mandates: On the one hand, they are nationalists, using both terrorism and conventional warfare against foreign occupation. At the same time, their ultimate objective is the establishment of a hardline Islamist theocracy in Somalia. Thus, al-Shabab can appeal to both Somalis who reject externally-imposed solutions to Somalia’s ills, and other Muslims who want to join the global jihad.

There is no doubt that this is a potent and intoxicating mix of ideologies. At least two of the 22 Minnesotan Somalis who joined al-Shabab have committed suicide bombings. There is no single reason why these men left for Somalia. Some may have been inspired by nationalist or religious fervor, others by a sense of dissatisfaction with their lives. A few, like Zakaria Maruf, had long rap sheets and were chronically unemployed. Others, like Jamal Bana, were college students who deeply cared for their families. Several frequented the Abubakar As-Sadique Islamic Center, Minnesota’s largest mosque. In May 2013, the mosque’s former janitor was sentenced to 20 years in prison on five terrorism-related charges, including providing material support for al-Shabab by helping facilitate recruitment. The mosque did not respond to a request for comment. In their defense, however, the mosque hosted a press conference after the Westgate attack which featured over 20 different community organizations jointly condemning terrorism.

Indeed, members of the Somali community take great pains to point out that the majority of Somali-Americans reject al-Shabab and their tactics. (three people I talked to used the number 99.99 percent). “There is an overwhelming number of Somalis within Minnesota who are absolutely opposed to what is happening to a few young men within the community,” said Loven, the FBI spokesman.

Nonetheless, it’s clear that local support for al-Shabab is not limited to those 22 men alone. Amina Farah Ali, a woman from Rochester, Minnesota’s third-largest city, has been sentenced to 20 years on 13 terror-related counts. Her accomplice, Hawo Mohamed Hassan, was sentenced to ten years. Ali and Hassan went door-to-door in Rochester and the Twin Cities soliciting charity for Somalia’s poor. The money was then diverted to al-Shabab. On a wiretap used as evidence in the trial, Ali is heard saying, “let the civilians die,” to an al-Shabab operative in Somalia. After her conviction, Ali told the court, “I am very happy. I’m going to the heaven no matter [what] …. Also, you guys go to the hell…. We know God. We know justice. And also I’m very sorry for the one who doesn’t know God and who puts the injustice [on the people].” Nine others were sentenced on the same day as Ali and Hassan, while 18 more were charged with related crimes.

It is still unclear whether al-Shabab will try to attack the United States, or if the Minnesota-Somalia terror pipeline will reverse its flow. What is clear, however, is that al-Shabab is violently anti-American. And considering their history of brutal retribution against foreign incursions, it’s unlikely that they won’t respond to the attempted SEAL raid, or the recent missile strike of a top al-Shabab operative.

Most counter-recruitment strategies in the Somali community have been reactive. Bihi hears about a troubled kid and drives him to classes. The FBI refused to disclose specific investigative techniques, but does readily admit that information provided by “extensive outreach” with community members is a crucial component of their counter-recruitment strategy. But only one organization, Ka Joog, is truly proactive. By giving young people a strong support system and a love of American and Somali culture from an early age, its members believe they can prevent their children from developing the kind of disaffection that makes them vulnerable to terrorist recruitment.

Ka Joog, which means “stay away” in Somali, was founded by twelve young men in 2007. It was intended to be an ad hoc, grassroots effort at youth engagement. The founders didn’t think the organization would be permanent, but six years later, it has received an award from the FBI; its executive director has testified before Congress; and, at a White House event, President Obama told Ka Joog’s staff that he was a big fan of the organization. “It was absolutely amazing that the leader of the free world has heard of us,” said Mohamed Farah, Ka Joog’s 29-year-old executive director, who has lived in the U.S. since he was three years old.

Ka Joog’s most successful endeavor is its afterschool mentoring program, which pairs Somali students from kindergarten through twelfth grade with someone a few years older. Students in the program show a 0.47 improvement in their GPA. Ka Joog has also begun Boy Scout Troop 252, teaching Somali boys swimming, kayaking, archery, and even shooting. “We make sure things are culturally specific—for example, we only serve halal food,” Farah said. “This also helps other people in other communities get to know us, because we compete against them, and it’s a good learning moment for everyone to learn about our community.”

A winter view of Minneapolis from atop the frozen Mississippi River. Photo: Charles N. Abbott (http://99cnaclasses.com/mn-minnesota-minneapolis)

The troop, as well as a summer camp on Lake Elmo and a girls-only trip to Yellowstone National Park with Wilderness Inquiry, helps Somali-American youth develop leadership skills in an all-American context. Ka Joog also runs programs like Invisible Art, where artists in a variety of different fields run workshops with local youth, giving Somali-Americans a platform to express their feelings creatively. Community leaders are invited to their performances, giving them a chance to understand the feelings of the younger generation through works that combine American and Somali artistic traditions.

Ka Joog’s headquarters are located on the top floor of Cedar-Riverside’s Southern Theater. When I visited, the theater was rehearsing an original play entitled Kung Fu Zombies vs. Cannibals. Ka Joog also has an office in the suburb of Eden Prairie—a demonstration of the Somali community’s increasing economic and geographic mobility—and has plans to expand to Rochester and St. Cloud. Someone in Utah has expressed interest in opening a Ka Joog chapter there, and discussions are under way for the Boy Scouts to collaborate with a similar scouting program in Somalia. They plan to coordinate via Skype, but if the situation in the homeland ever calms down, they hope to take the Scouts on a heritage trip. “In five years, we’re going to be an international movement,” Farah says. But that will only happen if they have the resources to realize their ambitions.

We’re a volunteer-based group fighting with an organization like al-Shabab that’s got millions of dollars. The federal government spends millions of dollars on counterterrorism, and that’s great, but we forget to do the same work on the ground level, on the local level. Private foundations are helping us here and there, but really we need our government to step up and get on the ground with us. I don’t want the community to be alone in this, and that’s what it feels like.

Farah says that people volunteer 40 to 50 hours a week for Ka Joog, such is their belief in the importance of their work. It was only last year that Farah was able to quit his job at a chemical laboratory in Saint Paul and concentrate on Ka Joog full-time.

To a great extent, the story of Somali immigration to the United States fits the classic Ellis Island paradigm. Immigrants come to America escaping war and persecution, and try to create a facsimile of the Old World in the New World. Their children are caught between assimilation and ethno-religious pride. Most are able to strike a balance, but a few swing too far in either direction. Some denounce their heritage as “backwards” or “primitive” and submerge themselves fully in the Melting Pot. Others over-idealize life “back home” and reject much of what America has to offer.

To solve this problem in the Somali community, the government needs to be financially supportive of people and organizations that are working on the ground to prevent terror recruitment—just as it funds social efforts to fight gang violence and dropout rates. Doing so will not only prevent affinity for al-Shabab from developing among Somali-American youth, but also increase the efficacy of other social programs.

On May 2, 2007, Mohamoud Hassan, a chemical engineering student at the University of Minnesota who voted “most friendly” by his high school classmates, wrote the following in a note on Facebook about al-Shabab:

These folks who claim to be a religious movement one day, a nationalist movement the other, or tribal militias when their back is against the wall, are only interested in one thing: To keep Somalia in the same state of hopelessness for as long as possible. They fight because in a state of hopelessness they are happy, in the anarchy they are strong and in the poverty of the masses they have plenty.

Two years later, Hassan was dead in Mogadishu.

What caused him to drop his university studies to fight for a terrorist organization he had previously decried? Was he radicalized after becoming more religious, or after the death of Somali civilians in an American drone strike? Was it the catchy recruitment videos he watched that enticed him, or did he grow disillusioned with America after the fatal shooting of his close friend?

All these factors—religion, nationalism, crime and poverty—are bound up together in the struggle for hearts and minds in the Twin Cities. If even the most outwardly successful Somali-American young man was susceptible to radicalization, then those on society’s margins are even more vulnerable. People and organizations in Minnesota are devoting their lives to preventing another Somali-American man from sharing the fate of Mohamoud Hassan and Jamal Bana. It is, in many ways, the newest front in the war on terror.

![]()

Banner Photo: Aiden Pink / The Tower