Yair Lapid has stormed the Israeli political landscape, founding a new party and upending everyone’s calculations. But it’s his father’s shadow that looms over a whole country.

In 1931, Yair Lapid’s grandfather purchased a leather-bound Haggadah in which he listed the annual participants in the family Seder. The Haggadah would survive the Holocaust, though its owner did not. The Jews of Novi Sade, the Hungarian city where Yair’s grandfather lived and his father Tommy was born, were expelled during the Holocaust. Yair’s grandfather, carted away before Tommy’s eyes, died at Auschwitz. In his book Memories After My Death, Yair recounts in his late father’s voice how Novi Sade’s surviving Jews, freed from the concentration camps and ghettos, returned to scrounge for their lost belongings. Tommy’s Uncle Pali “was amazingly lucky,” and found the old family Haggadah among the piles of rubble. In 1948, Pali would inscribe on the title page “the three most important words” in the history of the family: “Moved to Israel.”

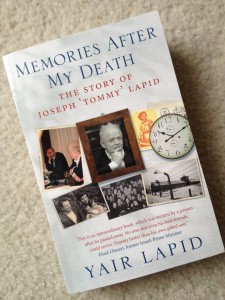

In a book replete with stories and anecdotes vying to represent the life of the legendary Israeli journalist and, later, political gadfly Yosef “Tommy” Lapid—Yair writes that his father told him the story of his life “again and again” — the tale of the family Haggadah stands out. In many ways, Memories After My Death is a kind of personal Haggadah, enacting the ritual of intergenerational Jewish storytelling between father and son; this Haggadah, however, is not about an exodus from Egypt to the biblical land of Israel, but from a Europe destroyed by Holocaust to the new Promised Land, the State of Israel. Memories aspires to be both an account of personal redemption, and a lens through which to view the story of national salvation, told by an up-and-coming, dutiful son channeling the proud voice of his late father — and giving us a glimpse of a nation being handed over, even retold, from one generation to the next.

Indeed, the question of fathers and sons haunts every page of Memories. “Will it surprise you,” Yair’s Tommy asks us at one point, “that I was always in search of a father?” The question reveals not only Tommy’s oft-stated desire to find a father to replace the one he lost in the Holocaust, but possibly Yair’s own version of the question: Who was his father, Tommy Lapid — child of the Holocaust, journalist, television personality, director-general of the Israel Broadcasting Authority (IBA); and finally, perhaps definitively, politician and minister of the interior?

This implies other questions, urgent for both Yair and all Israelis: Who is really telling the story of the father’s journey to the Promised Land? Who is Yair Lapid, leader of the Yesh Atid party — which won 19 seats in the last Knesset election — and as of this writing a likely minister in Benjamin Netanyahu’s government? And how will Yair live out the story inherited from his father? Yair, as Memories shows, is profoundly burdened by these questions.

Because of the book’s unusual narrative technique in which Yair speaks in his father’s voice all throughout, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the voices of father and son. Indeed, Yair ventriloquizes his father so well that the reader often forgets that Yair’s Tommy is a constructed character, and that Memories is a biography, not the posthumous autobiography it presents itself to be. Yair’s Tommy acknowledges that he speaks through Yair, but wonders whether his “voice has commandeered” that of his son; as he admits it did “more than once” during Tommy’s lifetime. The man who once served as justice minister, the Tommy obsessed with social, political and religious justice, wonders whether his life is marked by a defining injustice: Are the demands, he asks himself, that his legacy places on Yair “unfair to him, an injustice?” “I suppose so,” Tommy answers. The father’s expectations are a burden imposed upon the son, who must contend not only with the story of his father, but its telling.

Lapid constructs an Israeli family mythos, with himself in the role of JFK.

And so, Tommy tells us that, for him, Yair is his private response to the Nazis and the Holocaust, and the telling of Tommy’s story, the father’s story, is almost an urgent command: “Keep writing, my son,” he implores, “let me continue to tell you the story of my life.” Yet, from the grave, Tommy expresses remorse at the overwhelming power of that story. He fears that “like many children of successful people,” his son Yair will become a mere “Sancho Panza” to Tommy’s memories, “without bothering to develop an identity of his own.” It is possible that in this concern lies the reason why, as Tommy confides in us, his son Yair, now a grown man, sometimes sits in his office at night and weeps.

In a sense, Yair’s identification with his father, and the storytelling that brings his father’s past into the present, is an enthusiastic effort at constructing an Israeli family mythos, a kind of Kennedy family whose story ends in another real city on a hill—not Boston, but Jerusalem—with Yair as JFK and Tommy as founding patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy. For Yair, however, the question of whether the storyteller can ever tell his own story, independent of his father’s, remains. Does the son sitting at the Seder table — wise or otherwise — have anything to say for himself? Or just a repetition of the story lived and now told, through the son, by the father?

“Our parents,” Yair’s Tommy writes, “are our own dress rehearsals, and we are the dress rehearsals for our children.” Yair, it seems, wants to play the opening night for which his father rehearsed. But he also wants to tell the same story, reading his lines from the family Haggadah. Indeed, Yair’s pseudo-autobiography of his father testifies to his own doubts about whether he can free himself from the “very heavy shadow of a dominant father.” Yair’s Tommy wonders whether his son understands “that his father believed it was never too late to improvise.” This may suggest that, in some sense, Memories After My Death is the emotional autobiography of the son and not the father. As much as the book is about Tommy Lapid, in other words, its real meaning lies not in the details of Tommy’s sometimes astonishingly varied life, but in that of its author, Yair, and the questions raised by his father’s life: Can Yair improvise? And, if so, who will he become?

There are two Tommy Lapids in Memories: the open-minded pluralist and the single-minded egotist. The pluralist cultivates the voices of Israelis he believes have been silenced by extremists on both sides. Whether the extremists are secular Tel Aviv Laborites or ultra-Orthodox devotees, both are targets of his often blistering contempt. The second Tommy is the strident, unforgiving, combative egotist whose own voice and story are always at the forefront.

The first Tommy reveals a love of hybridity that has its origins in his own psyche. “My life story,” he begins, “is full of contradictions.” These contradictions begin with his own name or, more precisely, names: He is both “Joseph,” the name he chose to give to a Jewish Agency clerk at an unknown Israeli port in December of 1948, and Tomas, named “after a Hungarian prince from a long forgotten dynasty.” Bearing the names of the favored son of the patriarch Jacob and a Hungarian prince, Tommy embodies the tension—even conflict—between Western and Jewish cultures. Indeed, throughout his life, Tommy finds himself torn by conflicts of all kinds: As a child, he dreams that he is “two cats fighting each other”; he recalls having to choose, in another youthful manifestation of his “double existence,” between Serbian and Hungarian languages and identities. When a grade-school teacher writes “DECIDE” in block letters across one of Tommy’s assignments, which he has written in both Cyrillic and Roman alphabets, Tommy refuses to choose.

His own father, Tommy recounts, walked “dignified and deliberate” through the streets during the 1941 bombardment of Belgrade, while he himself remembers “running in a zigzag.” Tommy believes he survived because of this zigzag, which allowed him to avoid a falling telephone pole that nearly killed him, but the zigzag is also a kind of personal GPS that guided him through the rest of his life. “Life is not either/or but this and that,” Tommy says with conviction. “It is built on parallel lines that do not cross or contradict one another.” The hybrid Tommy lives with, even loves, contradiction and difference.

This first Tommy is reflected in the State of Israel he loves — a “sweaty, irritable, and vulgar country” of opposites. He expresses an almost Rabelaisian exuberance over Jewish diversity, which he meets face-to-face on the Yugoslavian ship, the Cephalus, which brings him to Israel. He sees “Jews from Croatia, Jews from Bosnia, Jews from Montenegro, Jews from south Yugoslavia, from cities and villages, the ultra-Orthodox, traditional Sephardic Jews, and shtetl Jews.” This Tommy wants to fill what he calls the “vacuum” left by the alternative extremes of old Labor-party socialism and fundamentalist ultra-Orthodoxy. The Knesset, he writes with admiration, is “filled with contradictions and contrasts, both high- and low-brow, clever and stupid, friendly and threatening,” and he, or at least part of him, longs for a public sphere that will match the diversity of Israel’s actual people and their representatives. His embrace of contradiction on a personal level reflects his political willingness to live with social and cultural diversity, to resist the temptation to definitively and finally DECIDE.

This “Tommy,” embracing the “this and that,” transforms his own hybrid personality into a cultural principle. He can claim that “real Israelis” — one of his favorite phrases — are not the caricatured “satirical puppets” of the rambunctious and polemical debates featured on the show Popolitika (of which he was one): Rightists are not always “fascists” and liberals are not always what he calls “Arab lovers.” Most of Israel, he suggests, lives outside of polemical extremes. This Tommy can even sympathetically quote an ultra-Orthodox journalist who says, “The world isn’t divided between Jews and Arabs or left-wingers and right-wingers or religious and secular,” but rather between those with a sense of humor and those without. The sense of humor that this Tommy celebrates abhors extremes, preferring to live with the contradiction and complexity that the dominant Israeli cultures — the extremes of left and right — have shown themselves unable to accommodate. Somehow, this Lapid finds himself agreeing, after the Rabin assassination in 1995, with his natural adversary, then-journalist and today head of the Labor Party Shelly Yachimovich: “The assassination was terrible enough as it was without anyone exploiting it to earn points in a debate.”

But this Tommy, silent and refraining from polemic and even debate; admitting that he is “sometimes here and sometimes there”; affirming, with Victor Hugo, that only “beasts of burden are consistent”; is accompanied in Memories by a second Tommy, a pugilistic egotist who can’t resist a “good fight.” He is a self-absorbed and self-confessed “conservative chauvinist” who admits to numerous prejudices against feminists, bleeding-heart liberals, ultra-Orthodox Jews, post-modernists, pampered women, and more. This “Tommy” has all the traits of an opposing alter-ego — single-minded, unable to brook opposition, even narcissistic — to the advocate of democracy and dialogue.

In the 1980s, Tommy goes to London on assignment for the Maariv newspaper, sets up shop at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park, and is reminded of what he already knew from his childhood under the Nazis: “That a person can speak passionately and persuasively about something that never existed and manage to win people over.” He notes that sometimes “our chaotic Israeli mess tends toward anarchy,” and that people “long for a strong man” at such times. For this “Tommy,” the “world is black and white,” and sometimes needs an “omnipotent boss” much like the one he imagines he was as head of the Israel Broadcast Authority.

This Tommy has seemingly endless delusions of grandeur. The newspaper mogul Robert Maxwell, for whom he worked and with whom he identifies, “did not like modest people any better than I did.” When he invokes Stalin and Roosevelt, he assures us that he does not “mean to compare myself to these people” as he implicitly does; elsewhere he claims, “I am not, of course, comparing myself to de Gaulle.” Of course. At another point, he introduces his opposition to the 2005 Gaza disengagement as a footnote to the Magna Carta, Winston Churchill, and David Ben-Gurion. When Tommy returns to Hungary in 1989, charged by Maxwell with negotiating the purchase of a newspaper and an army barracks to house it, the Hungarian commanding officer inquires about the two thousand plaster casts of Marx and Lenin the barracks still house. “Mr. Lapid,” he says, “what am I to do with them?” To which Tommy replies, “Smash them.” This “Tommy” is very distant from the pluralist one. The idols are broken, but one idol remains: “Tommy” himself.

Like Israel, Tommy Lapid “never missed a good fight or a good meal.”

This Tommy “never missed a good fight or a good meal,” choosing to both eat and live with gusto. And what he calls the “monumental role that eating played” in his family life is not just a culinary matter. His life contains a fraternity of fat men, among them his father, Robert Maxwell, and Ariel Sharon, with whom Tommy once shared “piles” of food at Sharon’s Negev ranch. Sharon, Tommy recalls, recounted how he emptied his refrigerator before going off to fight in the Yom Kippur War. The great warrior Sharon showed his appetite in both the dining room and on the battlefield, but Tommy “ate everything, I ate more than everyone, and I always remained hungry.” Only the eating habits of Yasser Arafat — “he ate more than I did” — seem to offend him. The hungry Tommy is an angry man; a man who, like Sharon, is always at war, voraciously consuming everything around him.

This second Tommy may also be aware of contradiction, but nonetheless declares “I contain everyone I know.” He encompasses everything himself. The self-proclaimed “most famous atheist in Israel” and avowed “public and bitter enemy of Orthodoxy” also “faithfully” represents “the entirety of Jewish fate.” The man who calls the Sephardic ultra-Orthodox party Shas “self-proclaimed big shots without a touch of God in their hearts” is told by one Shas member, “You speak against Jews all the time, but you’re one of the most Jewish people there is.” This “Tommy” does not need the ultra-Orthodox because he is already the best part of them; and of the impostors, he feels justified in saying, “I never grew tired of abusing them.” This self-absorbed, often demagogic “Tommy,” sometimes depicted with surprising admiration by the author of Memories, sits awkwardly next to the “Tommy” who celebrates the Israel he believes has been silenced by extremists.

The question of which Tommy more faithfully depicts the actual Tommy Lapid may be left to historians to work out. For us, however, a more pressing question is how these two Tommys, presented to us by an upcoming leader of Israel, will play themselves out in his own life. Will he embrace the finger-pointing demagogue, the Tommy who ends his “autobiography” with an empathic “I told you so”? Who knows in his heart, with de Gaulle, Maxwell, and Stalin, that sometimes people “need a strong-man”? Or will he embrace the Tommy who advocates for pluralist democracy, who wants to be a voice for Israelis who have remained silent? Will the role he inherits from his father be the one that recently announced, “In eighteen months, I will be Prime Minister of Israel”; or the one who has declared an agenda of inclusiveness, even telling his father’s “enemies,” the ultra-Orthodox, that “You have won, we need you”?

A hopeful possibility may be contained in his account of a conversation between “Tommy” and Yair’s sister, Meirav, a psychoanalyst. On why Tommy loathes so many people — liberals, settlers, the ultra-Orthodox — Meirav posits that “All your battles are characterized by this ‘life or death drama….’ ‘They’ are the winners. ‘They’ are Nazis.” It’s the “mark of the Holocaust,” she concludes. “All these ‘theys’ wish to destroy you, and you attack them fearlessly because if you let your guard down even for a moment you will lose everything.”

In Tommy’s response to Meirav’s diagnosis, one can hear not only his voice, but perhaps Yair’s as well, playing the new role of the rebellious son at the Seder table, rejecting at least part of his father’s legacy. “I have a very intelligent daughter,” Tommy retorts, “far more intelligent than her father.” Perhaps it is Yair speaking, and not just as his father’s sidekick, but as himself. Perhaps Yair prefers the wisdom of his sister to the unresolved antagonisms of his father. If so, if Yair is suggesting that the younger generation, already in the Promised Land, is no longer keen on a post-Holocaust sensibility marked by a polemical codependence between “us and them,” then perhaps there is a chance that he will choose the role of a leader willing to concede to perspectives other than his own.

Yet the question lingers. It is unclear for which role Tommy Lapid’s life was a “dress-rehearsal.” Will it simply be a repetition of the Lapid family story; the narcissism of the father relived in the dynastic aspirations of the son? Or will it be the more optimistic possibility of a post-Exodus, post-Holocaust story, in which Yair Lapid, the rebellious son, helps lead a national Seder in which his is not the only story being told?

![]()

Banner Photo: Flash90