The U.S. has made Israeli-Palestinian peace into a top priority. But how can you build a legitimate, peaceful state out of a kleptocratic regime?

If peace were suddenly to break out in the Middle East, John Kerry would undoubtedly assure his place in the Secretary of State Hall of Fame. Defiantly challenging a chorus of naysayers at home and around the world, Kerry launched a new round of Palestinian-Israeli diplomacy on July 29, 2013, and believes he can conclude a deal between the two sides by the end of April 2014.

He has his work cut out for him, however. Extremely difficult, almost impossible issues remain to be resolved, such as the status of Jerusalem, Palestinian refugee claims, and final borders.

But one obstacle is almost never discussed in public, yet has the potential to make even the most successful negotiation end in a spectacular failure. The present efforts to create a Palestinian state are built entirely atop a Palestinian political system that has long suffered from endemic corruption, abuse of power, nepotism, and waste. This problem has dogged the Palestinians at least since the establishment of the Palestinian Authority in 1994, radically undermining the most basic elements required for successful governance—including the faith of individual Palestinians in their leaders. This hinders the ability to administer international assistance, encourage investment, or build effective institutions.

Put simply, the current Palestinian regime, led first by Yasser Arafat and now by President Mahmoud Abbas, is ossified, brittle, and distrusted by the Palestinian street. The failure to address this problem would most likely lead to the birth of a failed state that crushes Palestinian freedom and economic growth, threatens Israel, and fosters radicalism—making American diplomatic efforts today seem, in retrospect, tragically flawed despite the huge investment of resources and political credibility.

Washington’s failure to address Palestinian corruption has already had catastrophic consequences. It had a decisive influence on the Palestinian elections of January 2006, in which the terrorist group Hamas and its allies defeated their secular rival Fatah, taking 76 of the 132 seats in the Palestinian parliament and earning the legal right to form a government.

As a result, the U.S. Congress legislatively prohibited any taxpayer money from aiding a Palestinian government in which terrorists played a role. Observers lamented the Bush administration for ignoring klaxon-level warnings that forcing elections that included an armed terrorist group was a grievous error and would see the Palestinian people bring them to power. And while there is no doubt that Hamas’ grisly record of suicide bombings and other attacks against Israeli civilian and military targets won over some of the Palestinian population, there was another explanation for its victory that many in the West preferred not to acknowledge: The Palestinians were looking for new leaders after years of living under a corrupt regime. Hamas ran for election under the banner of “change and reform,” and its message resonated.

The lost hope? Former Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. Photo: Catholic Church of England and Wales / flickr

There is no doubt that Fatah’s defeat was as long in coming as a victory for Hamas. As Zaki Chehab pointed out in his 2007 book Inside Hamas, Palestinians have increasingly come to view the group as not only a violent organization committed to confronting Israel, but also as an independent, less corrupt movement that refused to take part in a dysfunctional spoils system. Hamas was well aware of this, and worked hard to project the image of an organization impervious to the corruption that plagued the wealthy Fatah leaders who returned to the Palestinian territories after years of exile in Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia.

In other words, the most obvious explanation for Hamas’ success at the polls was Fatah’s failure to gain the support of the Palestinian majority due to its ineptitude and corruption. But the West was not interested in this point of view. As journalist Khaled Abu Toameh noted,

For many years the foreign media did not pay enough attention to stories about corruption in the Palestinian areas or about abuse of human rights or indeed to what was really happening under the Palestinian Authority. They ignored the growing frustration on the Palestinian street as a result of mismanagement and abuse by the PLO of its monopoly on power.

In fact, allegations of corruption against the Palestinian Authority have been constant since its establishment. In 1997, for example, the Associated Press reported that a Palestinian administrative report found “$326 million of the Palestinian autonomy government’s $800 million annual budget had been squandered through corruption or mismanagement.” As scholar Nathan Brown observed in his book Palestinian Politics After the Oslo Accords, the PA’s corrupt practices included “personal use of ministry cards, unaccounted international long distance calls, [and] padded expense accounts. A few were more significant, such as use of border controls to divert business to relatives of senior officials.”

A Haaretz report further quoted a Fatah official as saying,

Every honcho got himself a fat slice of the imports into the Authority. One got the fuel, another got the cigarettes, yet another the lottery, and his crony the flour. Gravel is a monopoly belonging directly to the security apparatuses, and they earn a fortune from it that finances their operations.

The official called these crony capitalists a “mafia” that undermined the Palestinian government. Another Palestinian official added that, “Without the monopolies, the economy could be in much better shape.”

Despite the airing of these troubling reports, the problem did not get better. In fact, throughout the decade that most defined Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking, the native problems strangling Palestinian civil society in the grave worsened, while diplomats looked the other way. According to Bloomberg News, PA president Yasser Arafat “diverted $900 million of the authority’s tax and business income to personal bank accounts” between 1995 and 2000. Another report from Bloomberg revealed that, between 1997 and 2000, the Palestinian leadership transferred $238 million to Switzerland without notifying its donors.

In September 2000, the peace negotiations collapsed, and after months of planning by Yasser Arafat, the PA launched the second intifada, destroying any prospects for peace that survived his refusal to accept Israel’s outreached hand and historic offers. Despite the violence, however, the Palestinians underwent a remarkable domestic awakening. Poll after poll revealed that a large majority was frustrated by the PA’s corruption, with the numbers peaking at an overwhelming 83 percent. Realizing that they had virtually nothing to show for seven years of state-building and a massive infusion of donor funds, many began to demand reform.

So even amidst the ongoing war with Israel, the Palestinians made an effort to clean house. After Arafat died in November 2004, the Palestinians elected Mahmoud Abbas as their new president. The West billed Abbas as the anti-Arafat, and the PA’s new finance minister, Salam Fayyad, was hailed for his commitment to reform and institution building. He steadily gained the confidence of the West.

A Palestinian man employed by Fatah displays his money after an ATM withdrawal at the Bank of Palestine in Rafah, southern Gaza Strip on June 8, 2012. Photo: Abed Rahim Khatib / Flash 90

Ultimately, however, the Abbas regime could not change the PA’s negative image among its own people. In the run-up to the 2006 elections, the Voice of America quoted Bassem Eid, head of the Palestinian Human Rights Monitoring Group, saying “everybody knows that Hamas is just climbing on such corruption of the Palestinian Authority. … I think that Hamas is getting more and more supporters, while the Palestinians start in the street talking about the Palestinian corruption.”

Hamas knew that corruption was a winning issue, and ran as the party of clean governance. The Associated Press reported that the movement was running ads that accused Fatah of corruption, nepotism, bribery, and larceny. Members of the movement held dinners and other events at which they pledged to tackle these issues. Their top leaders, including Ismail Haniyeh and Sheikh Said Siyam, did the same.

The strategy was wildly successful. When the results were in, Fatah, which had dominated the Palestinian national movement for decades, managed to win just 45 seats out of 132, disadvantaged by a complex electoral math that combined both direct and proportional representation. The dismal showing sent a clear message. One Fatah activist, Nasser Abdel Hakim, put it into words: The electoral loss, he said, was caused by “mismanagement and the corruption by the mafia that came from Tunis” when the PA was formed.

Statistics appear to substantiate this claim. According to the Congressional Research Service, “Hamas’ anti-corruption message during the parliamentary election was apparently successful and many reports and exit polls cited anti-corruption as a motivation to vote for Hamas.” Polling conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research found that “71 percent of those who considered corruption the most important consideration in voting voted for Hamas and only 19 percent for Fatah and 11 percent for the other lists.” Moreover, 25 percent of voters saw corruption as the number one issue in the election.

What followed was a stalemate. Israel and the U.S. both consider Hamas a terrorist group; as a result, they halted financial collaboration with the Hamas-dominated Palestinian government. Tensions between Hamas and Fatah supporters in the Palestinian bureaucracy steadily increased.

Soon enough, violence between the two factions erupted, leading to a period of lawlessness in the both the Fatah-dominated West Bank and Hamas’ traditional stronghold of the Gaza Strip.

In early 2007, Hamas abducted a string of Fatah and PA figures. The victims were often beaten and tortured. According to a Palestinian rights group, “limbs were fired at to cause permanent physical disabilities” in certain cases. In addition, Hamas hijacked a convoy of PA trucks. The violence became so bad that one human rights activist said Gaza had “become worse than Somalia.” Yasser Abed Rabbo, an executive committee member of the PLO, described the situation as “anarchy.”

On June 7, 2007, Hamas launched a brutal military coup to wrest the Gaza Strip out of the hands of the PA, which under power-sharing agreements maintained control of the official security forces in both territories. The battle didn’t last long. By June 13, Hamas forces controlled the streets and government buildings, including Abbas’ presidential and security compounds. By the following day, all of Gaza was under Hamas control.

The West, particularly the United States, went into panic mode after the coup, fearing that a similar takeover of the West Bank was imminent. Washington rushed to support Abbas with arms, cash, and intelligence. The message to the Palestinian leader was a simple one: Do not lose power in the West Bank.

It was at this point that Abbas likely realized there was little or no chance that the West would ever challenge his rule over the West Bank, and that weakness was his greatest strength. Thanks to the Hamas record of suicide bombings and rocket attacks, Fatah’s chronic mismanagement of funds seemed to mean very little. The West Bank Palestinian leadership concluded, quite correctly, that the West would turn a blind eye to its abuses of power, let alone its continued incitement against Israel.

Thanks to Hamas’ record of suicide bombings and rocket attacks, Fatah’s chronic mismanagement of funds seems to mean very little.

And that is precisely what happened. While Abbas’ patrons remained silent, PA corruption continued apace. In August 2007, just weeks after the Gaza takeover, a Palestinian news agency reported on “financial and administrative corruption in the Palestinian power company in Gaza.” The following year, the Jerusalem Post noted additional reports of problematic financial dealings. The Palestinian Authority also came under fire for stifling freedom of the press in the areas under its control. By September 2008, the Post quoted Husam Khader, a young Fatah leader, warning that former loyalists were leaving the party “because of the corruption and the traditional mentality of the Fatah leaders and because they ignore democratic aspects and democratic needs to heal Fatah as we wish.”

Since then, there has been little if any significant improvement in the situation. Abbas pushed Salaam Fayyad out of his position as Prime Minister in early 2013, eliminating the West’s trusted man and bringing Fayyad’s efforts to build accountable institutions and the foundation of a future Palestinian state to an untimely end. Meanwhile, the Palestinian leadership continued to stifle dissent at home by, for example, banning criticism of Abbas on Facebook. At the same time, it reportedly continued to squander international aid. A European Union audit concluded in October 2013 that the PA may have “misspent” $3.13 billion in financial aid in the previous four years alone. While some have cast doubts on the report’s veracity, the PA itself has acknowledged that corruption complaints in the West Bank quadrupled during 2013.

It seems clear that, despite being rejected by both the ballot and the gun, Abbas has failed to learn his lesson. He has failed to reform the dysfunctional Palestinian Authority, and does not show any signs of attempting to do so in the near future. And the West, addicted to top-down peacemaking, shows little interest in genuinely helping the Palestinian people attain a government dedicated to coexistence with Israel, nor one built on the open, fair and transparent civil society and legal system required to build a successful state.

Abbas, it should be noted, is not going anywhere. Four years past the end of his presidential term, with no elections in sight, despite regular tantrums in which he declares his departure is imminent, Abbas appears determined to continue in office until he is no longer physically able to govern. What happens after that is anyone’s guess. Abbas has no heir apparent and, according to Palestinian law, his designated successor is a Hamas member who became speaker of the Palestinian parliament following the 2006 elections.

Washington appears distinctly unconcerned by all this. Indeed, Kerry’s new peace initiative is marked by a strong willingness to throw money at the PA without a plan to bolster its ability to govern or end decades of financial mismanagement. In fact, the cash is already on the proverbial table: In May 2013, Kerry announced that the PA will be rewarded for reaching a peace agreement with $4 billion in aid. More recently, the White House’s Middle East Coordinator Phil Gordon stated that “stabilizing the Palestinian Authority’s finances” was an urgent goal for the administration, while also noting that the U.S. has already contributed $348 million to the PA this year.

Sadly, this means that the administration is now unlearning what past administrations took years to understand: Ignoring the issue of Palestinian governance is a mistake. Ambassador Dennis Ross, for example, who spearheaded the Clinton administration’s peace efforts, has said that “We should have been focused on the state-building enterprise. … We didn’t really focus on that until, in effect, after the collapse of Oslo.”

Aaron David Miller, who worked closely on Israeli-Palestinian peacemaking for over two decades, has said that Washington often turned a blind eye to the PA’s abuses of power, so long as the Palestinians maintained a public commitment to peacemaking diplomacy. “State security courts and human rights abuses?” he said. “Terrible. But you’ve got to keep the peace process alive. Corruption? Terrible. But you’ve got to keep the peace process alive.” Miller has expressed regret that Washington’s approach was transactional rather than transformational.

Elliott Abrams, who served as an advisor to George W. Bush, has also acknowledged that the problem of PA mismanagement and poor governance was well known to the administration, but “on corruption, we never had a program. We did not have a five-point plan.”

Indeed, for a time, the only plan the U.S.—and the West in general—had was to bet on Salam Fayyad and his efforts to clean up the PA. But now that Fayyad has been pushed out, there appears to be no plan at all.

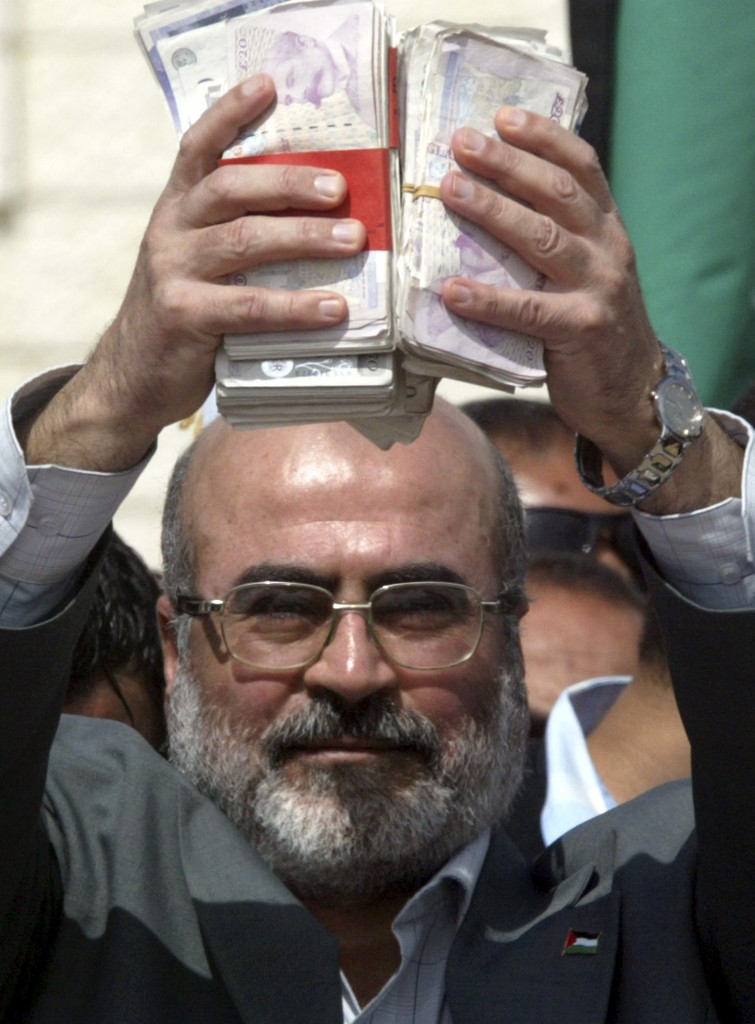

In Gaza, too, cash is still king. Hamas deputy prime minister Ziad al-Zaza holds up British pounds received from British MP George Galloway on March 10, 2009. Photo: Abed Rahim Khatib / Flash90

Theoretically, the United States could steer the Palestinians back to the Fayyad model, since it doesn’t really matter whether the effort is led by Fayyad himself, or by another competent leader with a commitment to reform and institution building. Unfortunately, this seems very unlikely to happen.

Today, American diplomats are falling all over themselves to placate the wrong Palestinian leaders. Washington’s goal is to reach a peace deal, pure and simple, even as the Palestinian government suffers from the same endemic corruption and abuse of power it always has. The failure to address these issues will inevitably give rise to the same wave of frustration that elected Hamas, an outcome that would threaten the very peace deal Washington hopes to foster. Furthermore, the best possible way to encourage the civil society needed for a stable state, let alone a durable peace, may be better achieved from the bottom up, rather than simply hoping that corrupt leaders will make it happen from the top down against the interests of their profitable patronage networks and their own continued enrichment.

In other words, administration officials continue to ignore the Palestinian struggle for good governance, despite the lessons learned from the election of Hamas and the Arab Spring movements that have recently toppled multiple Arab regimes similar to the PA.

Seemingly desperate for a peace deal and disinclined to challenge the Fatah leadership, Washington now appears only too willing to enter into yet another transactional relationship at the expense of a transformational one, and at the expense of a sustainable two-state solution.

![]()

Banner Photo: Israel Defense Forces / wikimedia