Iranians’ feelings about the West are both simpler and more complicated than visiting media generally conveys.

“O Master of the world, that metest out justice, look down, I pray thee, upon this innocent whom his brethren have foully murdered! Sear their hearts that joy cannot enter, and grant unto me my prayer. Suffer that I may live until a hero, a warrior mighty to avenge, be sprung from the seed of Irij. Then when I shall have beheld his face, I will go hence as it beseemeth me and the earth shall cover my body.”

—Shahnameh

In a 2015 interview with Jeffrey Goldberg of The Atlantic, President Barack Obama made his case for the nuclear deal with Iran. Despite its virulent anti-Semitism and other forms of extremism, he said, the Tehran regime “is practical, and is responsive to incentives, and shows signs of rationality,” and that this would likely lead to its compliance with the terms of the deal. He also said, in an interview with Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, that the ascension of Hassan Rouhani to the presidency, which he described as a victory over the so-called “hardliners,” opened up the possibility of a new relationship between Iran and the U.S., creating a political environment in which dreams of the future surpass grudges of the past. With a deal signed and passed, I traveled to Iran earlier this year to find out whether Obama was right.

I arrived at Dr. Moshen Keshvari’s Tehran office this past February, just as the people of Iran were about the elect their 10th parliament since the Islamic Revolution. The office was buzzing with activity, with a number of men in suits printing flyers on an antiquated black and white machine. The doctor was second on the conservative list for the Iranian parliament, and gave me an hour of his time a mere 23 hours before the election.

I got straight to the point: “Is this vote a referendum on the Iran deal?”

With a slight smile, Keshvari assured me that this was not the case.

These are uncertain times, full of threats from inside and outside the country, and we expect a record turnout because of it, but it is not an election about this deal but about the internal policies of this great country. People either want us, who will safeguard Iranian values and meet American promises with the suspicion they deserve, or they will choose the reformists who recklessly trust America and the West.

I asked him why that trust is reckless, and his answer was surprisingly personal.

“My brother was hit by mustard gas in the war with Iraq,” he explained. “I was much younger then, but I remember the sounds and the smells. My brother is alive but he shouldn’t be. He can’t breathe right and his skin looks like grated cheese, so he doesn’t like to show himself in public.”

Keshvari is in his 50s, a well-dressed man with a mild and soft-spoken demeanor. But there is an intensity about him, from his dark eyes to the careful deliberation with which he pronounces his perfect Oxford English. As we spoke, he leaned forward, emphasizing his words by pointing at me with a nicotine-stained finger.

More than a million of my people are either dead or injured today because we trusted the Americans and were made to be weak. You ask me why trust is reckless, but I ask you why would we trust America after what they did to us? If they could kill hundreds of thousands of our people and lie about it, what is to say they would not lie on a piece of paper to use us and discard us once again?

When I pointed out to Keshvari that many in America and the West believe that Iran was the winner in the nuclear deal and that Obama essentially surrendered to Iran’s demands, he smiled and said, “I agree.” Surprised by his honesty, I laughed and asked whether Iran can now move toward America with some confidence, starting a new relationship from a position of strength, but he told me that this would be as naive as it is for me to ask the question.

“Yes, we won these negotiations, but we did not win what the Americans were betting,” he said. “We will take what we want from this and do what we will. It’s like a proposal, Annika. Someone may ask for your hand, but if you don’t say yes there is no marriage.”

There was no shyness about Keshvari, and despite the fact that I am a Western, Jewish journalist with a record of pro-Israel writing, he didn’t seem to mince his words. With a sense of glee, he told me that, with the current power-shift in the Middle East, the West is finally about to get what it deserves.

“This is not a collaboration, nor is it the 1980s. This time we are not victims of someone else’s will, this time we are in control and get to rule ourselves for the good of our own people.”

It is certainly not the 1980s. In September of 1980, Saddam Hussein’s forces invaded Iran, igniting a brutal eight-year war between the two countries. Why Saddam chose to attack Iran is an issue still under dispute. Some say opportunism drove him to attack a weakened neighbor in a gambit to strengthen his position in the region. Others maintain that both during and after the Islamic Revolution, Iran had attempted to coordinate a Shia uprising in Sunni Iraq and Saddam had no choice but to clamp down on what he perceived as a planned Iranian coup. The Iraqi onslaught and the ensuing war took over one million Iranian lives and wounded almost as many, devastating the population and leaving a shocked, grief-stricken generation in its wake.

Almost every able-bodied male from 12-60 years old participated in the war. Two key factors caused the massive Iranian casualties: The Iranian military relied heavily on the “human wave” tactic, unleashing foot soldiers in thunderous but doomed bayonet charges unseen since World War I. In addition, Western nations—despite their alleged neutrality—provided Iraq with state-of-the-art weapons, including chemical weapons technology that would be used against Iranian soldiers and, later, Kurdish civilians in Northern Iraq. The combination of a self-destructive military strategy on the part of Iran and the fact that the West fed the Iraqis while starving the Iranians militarily led to massive loss of life and treasure, and to a wound that, a generation later, continues to bleed.

That wound is visible everywhere, even just outside my hotel on Ferdowsi Street where workers were preparing for Revolution Day, hanging decorations and meticulously gluing giant strips of photo paper, piece by piece, into a huge mosaic of the face of Ayatollah Khomeini as he returned from exile in Paris. Below the image was a sentence in Farsi. When my handler Reza arrived for my usual 9:00 AM pickup, I asked him what it said.

“Iran—victims never again.”

More than 95,000 Iranian children were casualties of the Iran-Iraq War – most aged 16-17, but some far younger. Photo: Wikimedia

He was taking me to a cemetery to see the graves of the Jewish martyrs, those who volunteered for the war three decades ago to prove their allegiance. It was a 45-minute ride through thick Tehran traffic, and Reza used the time as he always did, asking radically personal questions while leering at me. This time his focus was on my connection to Israel and Israel’s relationship to Iran. He wanted to know if the conflict between them influences how I view his country. Unwilling to answer, I turned it back on him and asked how he could hate Israel when he claimed to have taken such a liking to the Jews.

I don’t hate Israel and, though I know it’s hard to understand from the outside, there is a difference between hate and hate. Annika, to tell you the truth, I would love for Iran and Israel to work together and make America irrelevant in the Middle East. Together we would put them out of business. I don’t hate Israel. I hate America. Anti-Zionism is a slogan here, but Anti-Americanism is in our blood.

We’re just a few years apart, Reza and I, and in a different world we could have been friends, rather than the watcher and the watched. It is fascinating to me how invested he is in the idea of the regime and the revolution. Despite his promises of friendship and assurances that neither Judaism nor Israel is the preferred enemy of his homeland, I am no stranger to the realities he fails to mention. From the Supreme Leader’s inflammatory anti-Semitic tweets, to the now-infamous Holocaust cartoon competition, there is plenty of proof of the things my handler chooses not to disclose. It is often said by Western pundits and politicians that one must differentiate between the people and the regime, but nothing about my experience there validated that idea. Reza is protective of the revolution and the regime that holds him captive, going so far as to aid and abet their crimes. He prefers the captivity they offer to the freedom of the enemy. I asked him about the giant poster outside my hotel, about the message on it and what it means to him, and before he answered he lit a cigarette and offered it to me, in a rare moment of intimate familiarity.

It says it all, no? We got screwed, over and over, and it had horrible consequences. Everyone I know was affected by that war in some way and that’s true for everyone here. We were suckers, Annika. We won’t be suckers again–that’s what it means, I guess.

Despite knowing better, I tried to push him on this point. On a basic human level he wants the things I want, that much I assumed, and despite the flaws of the West, I would think that Iranians long for the freedoms and possibilities we enjoy. Why is he standing by this evil regime on the grounds of an inherited hatred, and how does that trump the human need to determine the course of one’s own life?

“I want this country to be more free, of course, and the tension here does get to me,” he said. “But I love Iran and when push comes to shove I am Iranian. When I meet the outside world that is only affirmed, that feeling only gets stronger. I want to see Iran vindicated, and it will be. Once we have our pride and strength back, freedom will come and things will get better.”

There is something admirable about the way the Iranian people wait patiently for a better day that keeps eluding them. That national temperament was tested throughout the war. After years of exhaustive warfare in which Iran regained most of its lost territory, Saddam Hussein began attacking Iranian shipping in 1984, moving the bulk of his military efforts into the Persian Gulf in order to damage Iran’s oil exports. Iran struck back, attacking tankers carrying Iraqi oil from Kuwait and Iraq’s Gulf allies. What would be known as the “Tanker War” began. By 1987, the U.S. and other non-combatant nations had moved in to protect shipping in international waters. At least, that was the official story, though it is commonly believed that Kuwait had requested U.S. protection for its assets in the Gulf. U.S.-Iranian relations, suspended after the storming of the American embassy in 1979, deteriorated even further in the wake of two major events.

In July 1988, the commander of the American warship USS Vincennes made a decision that would prove disastrous. He sailed into Iranian waters in pursuit of Iranian gunboats, but ended up firing shots at a civilian airliner, killing 290 people. The Reagan administration’s attempts to handle the situation only exacerbated the problem. It released an official explanation that to many outside observers seemed implausible at best, and awarded the commander of the Vincennes a medal for bravery. Many Iranians believe to this day that the incident was not, as stated by the Reagan administration, an accident, but a deliberate act of aggression against Iran. The Vincennes scandal was quickly followed by the Iran-Contra affair, and U.S.-Iran relations hit an all-time low. Iranians felt betrayed by the superpower, vowing to never again let America get close enough to hurt them.

Nowhere is that hurt more palpable than at the Blood Fountain. Despite its dramatic name, the water flowing from it is clear as day. It was built in the Beheshte Zahra cemetery in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq War as a monument to martyred soldiers. Several stories tall, the fountain used to flow with thick red water in memory of the fallen. After the “blood” garnered too much international attention, the government stopped coloring the water, but the fountain remains a permanent piece of marble propaganda. Reminders of the war that glorify martyrdom are everywhere I look in Tehran. Each street is named for a martyr, featuring plaques with faces and names. Murals by the side of each major road depict anti-American slogans and imagery decrying the Western world. It’s an open wound, and the regime makes every effort to keep it open, using it to counteract revolutionary sentiment and prove to their citizens that they stand alone in a world that is out to get them.

It works. Unlike anti-Israel sentiment, which is a mere appendage of hatred for the U.S., the disdain for America is real. Inculcated by the regime for decades, today it is found among Iranians of all ages and grounded in a deep sense of history and an underdog mentality—a feeling which, in their view, comes from having suffered as the world turned a blind eye.

Reza is visibly moved by the fountain and, as we stand there together watching the water, I start saying something but stop. Reza picks up where I left off.

“You are a Jew, so you have something in the history of your people that changed everything. You didn’t live through it, but it influences how you think and who you are. I have that, too. It changes everything, Annika, and it’s not that we can’t forget – it’s that we don’t want to.”

Reza is a 33-year-old man who lives every day under an oppressive totalitarian regime, and despite what I could only assume to be his natural longing for freedom, he was willing to set all that aside in order to right what he sees as a historical wrong. Like many other nations, Iran fought and lost a long war, and both Reza and Keshvari feel, with no small amount of anger, that they were deprived of their right and ability to win or lose on their own terms. This has turned into an obsession bordering on collective psychosis.

But there is some reason for it. The eventual end of the Iran-Iraq War brought yet more disappointment and humiliation for Iran. After bombing each other’s capitals and launching missile strikes on major cities, Iraq clearly had the upper hand. Iran was facing an astounding human and monetary cost for what had become the longest conventional war of the 20th century. In August 1988, Khomeini was convinced by then-speaker of parliament Akbar Rafsanjani to accept UN Security Council Resolution 598, which called for a ceasefire. The decision was blamed on what Rafsanjani said was the Americans’ insistence on not allowing Iran to win. They had, after all, provided Iraq with weapons and attacked a civilian airliner. Khomeini called the ceasefire a “chalice of poison” and in the minds of Iranians it was the U.S. that had forced them to accept it.

While the conflict was still raging, the UN Security Council issued statements that “chemical weapons had been used in the war.” But the UN statements never pointed out that only Iraq had used chemical weapons, and this ambiguous stance was vehemently criticized by the Iranian regime, which claimed to have proof that Iraq had used mustard gas and sarin on Iranians as well as Iraqi Kurds.

Even when the United Nations condemned Iraq’s repeated use of chemical weapons, the world still almost unanimously sided with Saddam Hussein, and Tehran felt it had been betrayed and isolated, especially by the United States. At this point, the regime turned most of its anger against America, citing a history of backstabbing–from America’s toppling of the democratically-elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh to its support for the despised Shah Mohamad Reza Pahlavi. The regime triumphantly declared that it had been right in dubbing the U.S. “the great Satan” in 1979, thus giving itself a false legitimacy by tying the revolution to the war.

It’s not that the Iranians can’t forget, it’s that they don’t want to, and when Obama said that Iran was rational, he misunderstood their rationality. The Obama administration, and to some extent the world, did not understand that the political arena is not a marketplace; not even $150 billion in unfrozen assets can buy the affection of a nation that has invested much more than that in hating you. The idea that the U.S. could conjure up a relationship with Iran through a quid pro quo, detached from history, is naive at best and reckless at worst. In seeking rapprochement through the nuclear deal, the Obama administration overlooked how central the hatred of the U.S. is to the Islamic Republic. It shapes both its identity and its ideology. The regime’s anti-Americanism gives the regime its raison d’etre and enhances the country’s image throughout the Muslim world. The conflict with the U.S. lends credibility to Iran as it expands its influence in the Middle East.

The Iranian takeaway from the Iran-Iraq War was that the U.S. led them to death and dishonor by actively preventing them from winning, and that the world took their lead and turned a blind eye. President Obama wagered that the Iranian people are dreaming of a Western life, friendship with America, and a counterrevolution to set them free. It is a beautiful and somewhat melodramatic idea, but it is detached from reality. Iranians do not want to buy what he is selling. They have swapped freedom for a sense of honor and hope for eventual revenge. Unfortunately, Obama lacks the humility to take them at their word.

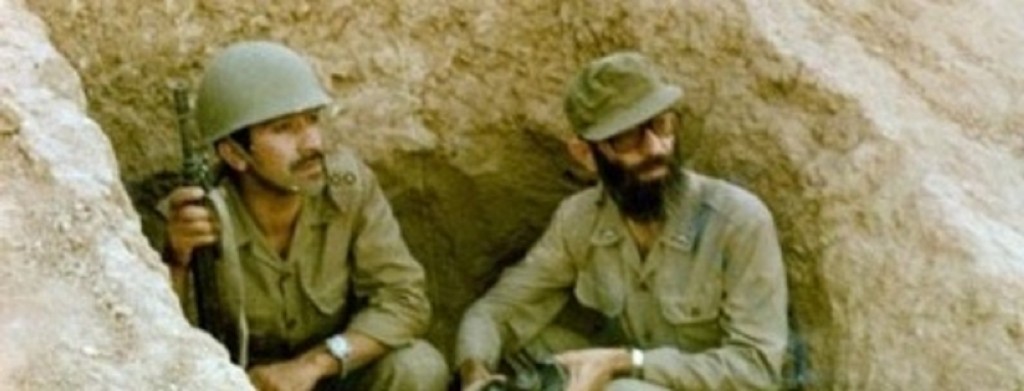

Ali Khamenei (right), now the Supreme Leader of Iran, in a trench during the Iran-Iraq War. Photo: Wikimedia

And what he cannot understand is why Iran’s totalitarian regime survives: It deeply understands its people. The Iran-Iraq War serves as both carrot and stick for the country’s rulers. The regime uses the war to prove that the West cannot be trusted and that Islamist rule is the only thing that can prevent a similar catastrophe. Iran views itself as an underdog, patiently waiting for its day. Ironically, Obama’s deal has brought Iran that much closer to achieving that coveted independence. The regime can claim victory, solidifying the legitimacy of its rule.

“A victory for diplomacy over war” is what Obama called the Iran deal. The day after that comment, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei tweeted a picture that appears to show Obama with a gun to his head. Obama chose not to respond. But the image was very telling: To Iran, it was never diplomacy or war, but rather diplomacy, then war. The gun remains to the Americans’ head. The deal only strengthened the resolve of the regime and its legitimacy in the eyes of the Iranian people, giving them a sense that they are regaining their national dignity and pride.

As I leave Iran on the eve of Revolution Day, I see schoolgirls dressed in the obligatory chador taking pictures against the backdrop of a mural depicting a handshake. One arm is painted in the American flag, the other in the colors of the Islamic Republic. From the sleeve of the American arm comes a knife, like a shiny Trojan horse. This is how the memory of betrayal is handed down through generations, making them guardians of the revolution and mourners of the past rather than activists for a future that could dismantle an oppressive dictatorship.

President Obama does not put much value in old promises, ancient history, and timeless faith. That is his prerogative, but his mistake is in assuming the rest of the world shares his indifference. The president was right that the Islamic Republic of Iran is highly rational, but he fails to understand that hating America is rational to them, much more so than forging a friendship with an entity they see as responsible for a humiliating defeat and their current hardship.

![]()

Banner Photo: GTVM92 / Wikimedia