A new book explores how a week-long war—one barely covered in college history courses—explained the subsequent sixty years of American foreign policy in the Middle East.

American presidents make the same foreign policy mistakes over and over again. Intervening when they should not. Sitting on the sidelines when it’s the worst possible choice. Treating friends and allies like dirt while trusting duplicitous hostiles. If, as Karl Marx said, history repeats itself first as tragedy and a second time as farce, what are we supposed to say when history repeats itself decade after decade ad infinitum?

Historians are tasked with delivering us from George Santayana’s curse, where those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, but historians can only save those who take the time to study the historical record, and even then it only works if the historical record is accurate.

Thank goodness, then, for Hudson Institute senior fellow Michael Doran’s valiant attempt to save us from ignorance and bad history in his bracing new book, Ike’s Gamble: America’s Rise to Dominance in the Middle East. He expertly walks us through the Suez Crisis of 1956 and its ghastly aftermath when Republican President Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower learned the hard way that Israel, not Egypt or any other Arab state, should be the foundation of America’s security architecture in the Middle East.

When Eisenhower began his first term in 1953, the Cold War was just six years old. Not every country had chosen a side yet. The Middle East and North Africa were for the most part non-aligned, and Eisenhower hoped to bring the Arab world into the American camp.

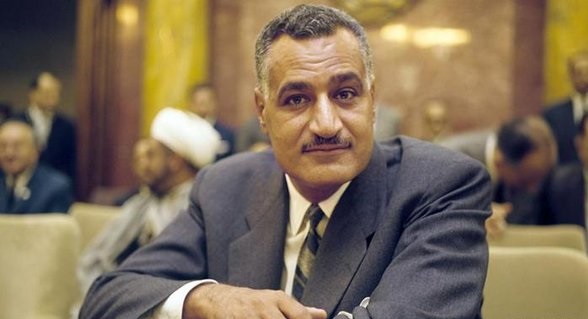

Great Britain and France were still the predominant Western powers in the region, yet a nationalist anti-colonial wind was blowing—especially in Egypt, where the self-styled Free Officers, led by Mohammed Naguib and the charismatic young Gamal Abdel Nasser, had overthrown King Farouk the previous year. At the time, Nasser and other nationalists in the Arab world seemed to be the vanguard for an entire region, and if Eisenhower wanted the Arabs to stand with Washington against Moscow, he’d have to get on their good side.

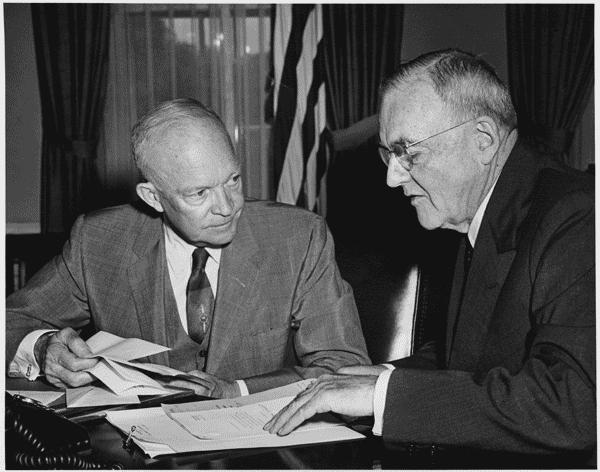

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower meets with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles at the White House, August 14, 1956. Photo: National Archives Catalog

Ike was in a tough spot, though, since America’s traditional allies were still colonial powers. Britain and France had drawn most of the Middle East’s borders after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in the waning days of World War I, and they’d installed and continued to maintain several governments in that part of the world. In Egypt’s case, Britain garrisoned troops in the Suez Canal, and both British and French investors owned the Suez Canal Company, which kept almost all the profits from ships transiting to and from the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Hostility to the new state of Israel was also rampant from Baghdad to Rabat, especially in Israel’s borderland countries like Egypt.

So Ike and his foreign policy team felt compelled to distance themselves from Britain, France, and Israel to prevent the Arab states from aligning themselves with the Soviet Union. Nasser was fast becoming a leader in region-wide Arab politics, and he wanted what remained of the British Empire out of Egypt entirely. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles—both natural anti-imperialists—decided to act as an honest broker, as they put it, between Cairo, London, Paris, and Jerusalem.

The U.S. hosted talks between the British and the Egyptians over the status of Britain’s military base in the canal zone, and the Americans effectively took Egypt’s side and strong-armed Britain into signing an agreement mandating a withdraw of all of its soldiers within 20 months. With one victory under his belt, Nasser went after the next. He nationalized the Suez Canal Company, even though it wasn’t supposed to be under Egyptian control until 1968 per the treaty, and he closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping.

On October 29, 1956, Britain, France, and Israel invaded Egypt simultaneously and left Eisenhower holding the bag. Ike thought military action was the worst possible response, but at the same time he hoped for a quick Western victory, and he was exasperated with British delays and incompetence. Even so, he reluctantly took Egypt’s side and imposed crippling economic sanctions that effectively deprived Europe of imported energy. “Those who began this operation,” he told his aides, “should be left to work out their own oil problems—to boil in their own oil, so to speak.”

Britain had no choice but to withdraw, followed by France and Israel.

Ike didn’t feel comfortable doing any of this. Britain and France were American allies, after all, even though they behaved recklessly. He simply felt that he had little choice. “How could we possibly support Britain and France,” he said, “if in doing so we lose the whole Arab world?”

Nasser had conned Eisenhower, however, and he had done it masterfully.

If you’re familiar with the history of the region, you already know that Nasser aligned Egypt with the Soviet Union anyway and whipped up the Arab world into an anti-American frenzy. Ike’s gamble failed. Nasser’s heart was with Moscow all along. He cleverly used Eisenhower as a tool for his own ambitions and planned to stab the United States in the front from the very beginning.

One of Nasser’s deceptions should be familiar to anyone who has followed the painful ins and outs of botched Arab-Israeli peacemaking. Over and over again, Nasser used a strategy Doran calls “dangle and delay.” He repeatedly dangled the tantalizing idea of peace between Egypt and Israel in front of Eisenhower’s eyes, only to delay moving forward for one bogus reason after another. He never planned to make peace with Israel or even to engage in serious talks.

Nasser did, however, participate in theatrical arms negotiations with Washington that he knew would never go anywhere.

Eisenhower wanted to equip the Egyptian army. Nasser wasn’t stupid, though. He knew that Ike would attach strings to the deal. Egypt’s soldiers would need to be trained by Americans, and they’d be reliant on Americans for spare and replacement parts. Nasser really wanted to be armed by and tied to the Soviet Union, but had to pretend otherwise lest Eisenhower side with Britain, France, and Israel. So Nasser slowly sabotaged talks with the United States in such a way that made Washington seem unreasonable. That way, when he turned to the Soviet Union for weapons, he could half-plausibly say he had no choice.

Nasser did such a good job pretending to be pro-American that he convinced the United States to give him a world-class broadcasting network that allowed him to speak to the entire Arab world over the radio. Washington expected him to use his radio addresses to rally the Arab world behind America against the Russians. Instead, he used it to blast the United States with virulently anti-American propaganda and to undermine the West’s Arab allies. “Nasser,” Doran writes, “was the first revolutionary leader in the postwar Middle East to exploit the technology in order to call over the heads of the monarchs to the man on the street. Suddenly the Hashemite monarchy [in Iraq and Jordan] found itself sitting atop volcanoes.”

Nasser strode the Arab world like a colossus after his American-made victory in the Suez Crisis, and he became more brazenly anti-American as he gathered strength. Conning Ike was no longer possible, but Nasser didn’t need the United States anymore anyway.

Unlike some American presidents, however, Eisenhower learned from his mistakes. In 1958, five years after being sworn into office, he reversed course. Rather than suck up to Egypt, Ike deployed American Marines to Lebanon to shore up President Camille Chamoun, who was under siege by Nasser’s local allies.

“In Lebanon,” Eisenhower wrote in his memoirs, “the question was whether it would be better to incur the deep resentment of nearly all of the Arab world (and some of the rest of the Free World) and in doing so risk general war with the Soviet Union or to do something worse—which was to do nothing.” That is almost verbatim what the British said to justify their own war against Nasser when Eisenhower slapped them with crippling sanctions.

Reality forced the United States into a total about-face. Ike’s entire Middle Eastern worldview collapsed. Even before sending the Marines to Lebanon he announced that America was taking Britain’s place as the pre-eminent power in the Middle East. He had to start over even if he didn’t want to. “Nasser,” Doran writes, “the giant who rose from the Suez Crisis, crushed Eisenhower’s doctrine like a cigarette under his shoe.”

What happened between the Suez Crisis and Eisenhower’s intervention in Lebanon? A couple of things.

Ike’s hope to bring Syria into the American orbit alongside Turkey and Pakistan collapsed in spectacular fashion. So many Syrians swooned over Nasser after Egypt’s victory in the Suez Canal that Syria, astonishingly, allowed itself to be annexed by Cairo. Egypt and Syria became one country—the United Arab Republic—with Nasser as the dictator of both.

Washington’s attempt to groom Saudi Arabia as a regional counterbalance to Egypt also hit the skids when Nasser accused the Saudis of trying to assassinate him and foment a military coup in Damascus. The Saudis responded by shoving King Saud aside and replacing him with his Nasserist younger brother, Crown Prince Faisal.

The final blow came with the brutal overthrow of the pro-Western Hashemite monarchy in Iraq and the mutilation of the royal family’s corpses in public, thus toppling the last pillar of America’s anti-Soviet alliance in the Middle East. Eisenhower had no choice but to stop being clever and return to the first rule of foreign policy: reward your friends and punish your enemies.

Rewarding friends and punishing enemies has been the traditional foreign policy for all powerful states since the time of antiquity, and for one simple reason—because it works. Anything else is almost always disastrous. No, you will not win every battle or war this way, and yes, sometimes you have to work with one enemy to defeat another. But working with enemies to defeat friends is all but guaranteed to blow up in your face, as Eisenhower and so many others have learned the hard way.

Eisenhower learned some other stark truths the hard way that still confound American foreign policy makers today. The Arabs are not a monolithic bloc and never have been, and the tired divide between Sunni and Shia Muslims is just one of the fracture lines. In addition to religion, they are divided by tribe, by region, by national origin and by ideology. They are as united in their hatred for each other as they are in their hatred against Israel.

“The revolutionary wave that swept the Middle East after the Suez Crisis,” Doran writes, “gave Eisenhower an intensive course in the complexity of inter-Arab conflict. The wave produced a long series of crises—one day in Syria, the next in Jordan, and the day after that in Lebanon—none of which had the slightest connection to imperialism or Zionism. As a result, Eisenhower learned that, because the Arabs were perpetually at each other’s throats, no effort to organize them into a single bloc has a chance of success.” Not even Nasser himself could pull that off.

Nasser, in the end, was a megalomaniacal wrecking ball, and he would have wreaked far less destruction had Eisenhower not fallen for the long con and enabled the Egyptian dictator during his rise. “Nasser,” Doran writes, “was Frankenstein’s monster. His great achievements, the triumphs on which his reputation was built, were entirely made in America.”

Eisenhower never admitted in public that he let Nasser con him or that he should have sided with his European allies instead. He never acknowledged to the world that he botched Egypt. He always insisted that what he did was right, and conventional historians have by and large agreed with him.

Ike’s Gamble is an overdue corrective. Doran all but proves that Ike regretted his early foreign policy privately. Eisenhower confessed to a number of people off the record that he wished he’d handled Suez very differently. One of those people was his vice president Richard Nixon—hardly the most reliable source. Eisenhower said the same thing, however, to several esteemed diplomats from Europe and the Middle East, and in any case, his foreign policy was strikingly different after the botched Suez Crisis than it was before. “Like all politicians,” Doran writes, “Eisenhower was loath to admit publicly that he had blundered, but the brutal truth hung before his eyes like a corpse on a rope.”

No more would Eisenhower throw his support behind an Arab state—especially not Nasser’s Egypt—at the expense of America’s traditional allies. The list of American allies included the state of Israel which Ike saw in time not as liability but as an asset.

The Israelis will tell you that the first rule of diplomacy in the Middle East is “don’t be a sucker.” Eisenhower allowed himself to be suckered. He wasn’t suckered because he was stupid. He simply believed a few things about the Middle East that seemed true but weren’t.

Those things were these: that Egypt, as the most powerful Arab country, could deliver the entire Arab world to the Americans in the Cold War; that the major obstacles were European colonialism and Zionism; and that the West needed to woo pan-Arab nationalists like Nasser because they would eventually lead the whole region. These ideas were wrong, but they were not controversial. On the contrary, they were conventional wisdom in Washington at the time, and they comported nicely with Eisenhower’s brand of Republican anti-imperialism. “It is impossible,” Doran writes, “to exaggerate the impact that the image of America as an honest broker had on Eisenhower’s thought. Words like idea, concept, and strategy mischaracterize the nature of the vision. Terms like paradigm, worldview, or belief system are more apt.”

Eisenhower, Dulles, and just about everyone else in Washington therefore believed that resolving the Arab-Israeli conflict and winding down European colonialism mattered more than anything else in the region, and they paid virtually no attention at all to inter-Arab conflicts, Nasser’s messianic quest to rule all the Arabs from Cairo, and his intent to use Soviet backing to do it. Ike wasn’t interested in distant parochial Arab conflicts. They hardly even registered. He had no place in his worldview to put them. He just wanted to keep the Soviet Union out of the Middle East, and he botched it. Before the end of his second term, the Soviet Union counted not only Egypt as an ally, but also Syria and Iraq.

Why does any of this matter today? Because two of Eisenhower’s wrongheaded ideas are as hard to kill as the Terminator—that the Arab world is a homogenous monolith and the related notion that an American alliance with Israel harms our relationships with Arabs everywhere. Neither of these things are true, and they never have been. America’s natural allies in the Middle East either tolerate our friendship with Israel or secretly hate Israel less than they let on in public, and Israel’s most vicious enemies will never side with the United States anyway. Eisenhower and Dulles eventually figured this out, but American presidents and foreign policy makers have the damnedest time learning from the mistakes of their predecessors.

“The Israel factor,” Secretary of State Dulles wrote before he wised up, “and the association of the United States in the minds of the people of the area with French and British colonial and imperialistic policies are millstones around our neck.” There is a kernel of truth to that, but it’s almost beside the point. Middle Eastern people and rulers despise each other as much as, and sometimes even more than, they despise Israel. That has been true since the day Israel was born, and it hasn’t stopped being true for even five minutes.

Eisenhower infuriated the Egyptians simply because he tried to forge an alliance with Iraq against the Soviet Union. Nasser’s propaganda machine, Doran writes, “treated it as the crime of the century.” Ike did not see that coming. The British did, though, because they’d already learned that if you can’t afford to enrage Arab leaders, you can’t make alliances with anyone in the Middle East, Jewish or Arab.

“The honest broker worldview,” Doran writes, “instilled in Western officials a perverse desire to shun friends and embrace enemies.” That was back in the early 1950s, long before I was born. Washington hasn’t changed much in the meantime.

![]()

Banner Photo: Imperial War Museum