The latest bogeyman for Israel-bashers is the Zionist summer camp, which purportedly turns our children into fascists. For former campers as well as those who never went, a refresher course on summers at the lake.

Forget New York: The nexus of American Jewish cultural and political achievement is found deep in the woods of northwestern Wisconsin. Want to see it? Drive north from Siren and just keep going. Past the drive-through liquor store. Past the canoe still wedged into a tree. Past the signs in Webster advertising the “meat raffle” (it’s exactly what it sounds like). Hidden in the expanse of red pines is Herzl Camp, a Jewish summer camp where I spent six years as a camper and another four as a counselor.

OK, so maybe “nexus” is a little strong, but take a look at some of the camp’s other alumni: Bob Dylan. The Coen Brothers. Thomas L. Friedman. Debbie Friedman. Abe Foxman. The guy who wrote “Funkytown.” Those are some serious Elders of Zion. In fact, it’s not surprising that someone harboring dark obsessions about Jewish power and influence in American life has begun to connect the dots (how else can you explain “Funkytown’s” success?).

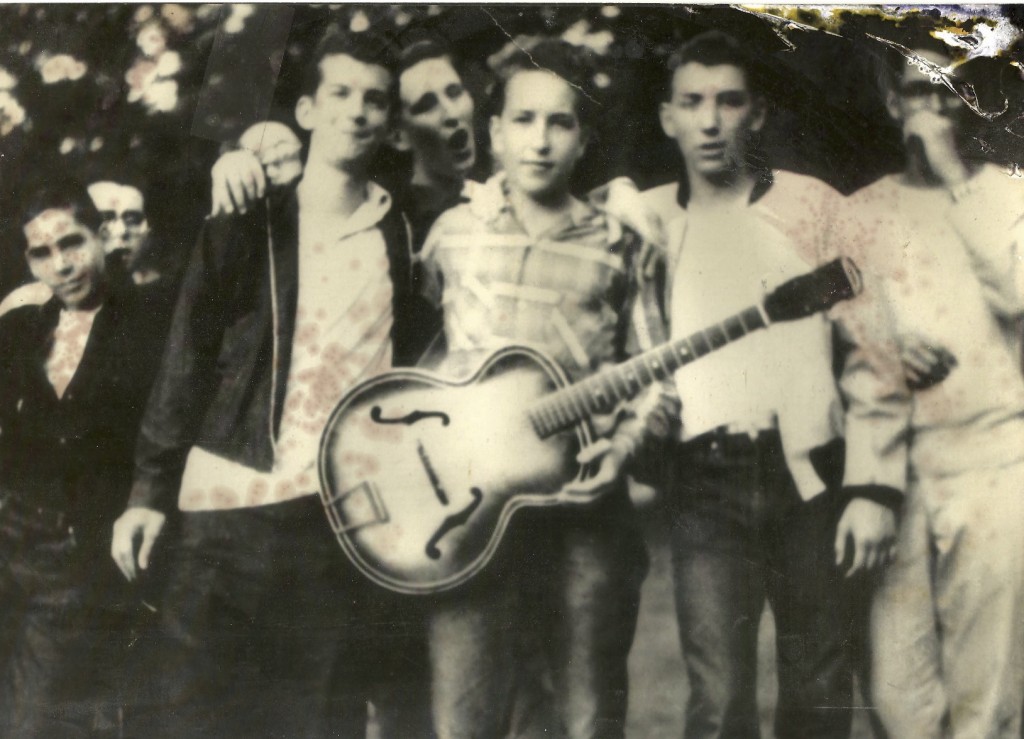

The Coen Brothers were recently interviewed on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross about their new movie, Inside Llewyn Davis, which is about a Bob Dylan-esque folk singer. Gross mentioned that Dylan and the Coens had all attended Herzl Camp. One of the Coens (the interview was on radio, so I couldn’t differentiate between them—let’s call them Acerbic Coen and Sardonic Coen) thought that Dylan’s Herzl heritage was merely an urban myth, but Acerbic Coen pointed out that no, Dylan’s biography features photos of him playing his guitar at the camp.

“Is this the kind of summer camp where you sing songs with lyrics about how great the camp is, and then there’s team songs with how great the team is?” Gross asked.

“No,” said Sardonic Coen. “It was a Zionist summer camp, and you sang Zionist songs in Hebrew.” He said that last sentence in the same tone that he might have said, “The doctors botched my hernia operation” or “We got beaten at the Oscars by The English Patient.”

Herzl Camp, 1957. From left to right: Larry Keegan, Jerry Waldman, Robert Zimmerman (AKA Bob Dylan), Louis Kemp, David Unowsky.

So, from this nugget of Zionist geography (it’s like Jewish geography, but more sinister), Philip Weiss, proprietor of the rabidly anti-Zionist site Mondoweiss, extrapolated that “American Jews need to take that indoctrination apart to understand who we are as religious supporters of settler colonialism.” Those are some pretty serious charges. Was I indoctrinated as a nine-year-old to support “settler colonialism”? I was on the camp’s education team for three years when I was on staff—am I complicit in brainwashing children and teens?

I am a Zionist because I decided, when I was eight years old, that I wanted to be Bob Dylan when I grew up.

My dad had to go on a lot of long business trips at the time, so whenever he was home I would make sure to follow him around everywhere, even on errands. So it was that in early November 2000, I trundled along with him to Best Buy, where he bought the two-disc The Essential Bob Dylan album. I didn’t really care that much about music at the time, but my dad popped the first disc into the CD player and told me to listen, really listen to the words. “Blowin’ in the Wind” I had heard before, but the second track, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” absolutely floored me: the deceptive simplicity of the lyrics, the sarcasm masking the inner pain and confusion. I demanded from the back seat that we listen to it again. I listened to those CDs almost nonstop for the next few months.

I felt a lot of affinity with Bob: We were both socially awkward Minnesota Jews with very limited singing skills. For my ninth birthday, I got a Dylan biography, which, in retrospect, I probably wasn’t ready for. But I was determined to be the next Dylan, and so I tried to follow in his footsteps in every way a nine-year-old could: Playing piano and guitar, listening to lots of old music, and imagining myself intellectually superior to all of my peers. And since Bob went to Herzl Camp, I was going to Herzl Camp. Even though none of my friends were going. Even though I had never successfully made it through a sleepover. I had had plenty of sleepover attempts, but I would always get too homesick and call to be picked up. My parents made it very clear to me that they were not going to drive to Wisconsin to pick me up. That fact became more and more prescient as the departure date drew closer. How would I survive a whole week?

June 19, 2001: A convoy of coach buses snaked its way northwest from Minneapolis. I was too anxious to take a nap or try to make friends with the other boys on the bus. Mostly I just listened to the Dylan CD on my Discman and stared out the window. We drove through Siren, where the landscape looked like the aftermath of an alien invasion. A gas station was stripped of everything but its shell. Power line towers lay prone on the side of the road. I saw a dead cow in a field, and a canoe wedged into a tree. An F3 tornado had hit Siren the night before, killing three and causing $10 million of property damage. I ran to the counselor at the front of the bus. “Are we going to be OK?” I asked.

“Of course we are,” he said. “Herzl Camp is the safest place in Burnett County.”

The buses drove through the gate and parked us outside the auditorium, and we were shepherded inside, where we were blasted with a wave of sound so powerful that everything seemed to be vibrating. Eventually my ears adjusted to the point that I realized that everyone was singing Hebrew songs. I went to Jewish Day School, so I already knew some of the songs, but I also knew that it wasn’t cool to enjoy singing them. I wanted so desperately to be cool, to be Dylan, and since almost no one knew me at camp, I could reinvent my identity. I didn’t have to be the nerdy kid who liked to, ugh, participate in things. So I was amazed that the older campers (who were by definition cooler) were the loudest ones singing, even louder than the counselors who were paid to be there. So I started to sing along, softly at first, and then with more and more vigor. The songs faded away, and the cheers began, which I quickly learned and joined in on, even though the cheers were for sessions I wasn’t in. Eventually, with some fits and starts, the cheers died down. The director called my name, and sent me to tzrif 4—Cabin 4—where I had the most fun week of my life.

Jewish camps may have different priorities, but all are focused on nurturing a strong Jewish identity. Some are more interested in Israel—Young Judaea camps are pretty clear about embracing aliyah. Other camps, like Camp Ramah of the Conservative movement or the many camps of the Reform movement, highlight specific religious approaches to Judaism along with swimming and flag football. Herzl Camp is an independent camp, unaffiliated with any denomination of Judaism. And like Jewish summer camps of all varieties, it is designed to inculcate the feeling within young Midwestern Jews that the coolest thing in the world is being proud of who you are. And the best way to express that pride is to do it as loudly and creatively as possible.

At Herzl, there’s a cheer for every occasion, and an occasion for every cheer. There are cheers for each session and each cabin, and individualized cheers for most staff members and some campers. There are cheers for each team during color wars, cheers in English and cheers in Hebrew. There are cheers for specific foods and specific meals, and cheers in appreciation for the kitchen staff. There are cheers for arts and crafts and rock climbing and even fishing. There are ruach (spirit) battles, where cabins compete to see who can cheer for themselves the loudest. There are even cheers to get people to stop cheering. Every year there are new activities and new people at camp, so every year, campers and counselors come up with new cheers. What you’re cheering for may be kind of silly, and you may not have chosen it if you had the option, but for one reason or another, you ended up in this group. So why not own it? Why not be proud of it? And why not work to make it even better?

Thursday night all-camp cookout. The burgers were kosher—coincidence or conspiracy? Photo: Jonathan Edelman

Another value of being at such a camp is that counselors and even campers are given wide latitude to propose and implement improvements. Want to start a band and perform in front of camp? Go for it, use this space to practice. Think the benches in the auditorium aren’t comfortable? Someone will teach you to build new ones. What you do at camp, what you do in life, is only limited by your imagination and ambition, because if you will it, it is no dream.

All told, I spent 49 weeks at Herzl Camp. That’s less than a year. But my experiences there were so immersive, so meaningful, that nearly every day I do something that inadvertently reminds me of camp, or of one of the friends that I made there. Herzl is where I learned how to set the table and make my bed, so repeating those mundane activities always bring me back. But I also learned more ineffable things: How to make a plan and execute it, how to broker compromise, how to lead and how to delegate.

If there’s one thing that always causes flashbacks, though, it’s chicken nuggets. Chicken nuggets are my Proustian madeleine, especially if they’re burnt: We would have them every Saturday lunch, with burnt potato latkes and (somehow) burnt applesauce. All of camp used to have proto-Kobayashi competitions over who could eat the most nuggets. Once I sat next to an Israeli counselor named Liav, who ate 126. It was a triumph that had him in the bathroom for the next three days.

It was funny how I could always eat so much and yet return home skinnier than when I left. I suppose it was all of the running around I did—four chugim a day (I almost always did sports or swimming), plus a cabin activity and a session-wide activity, plus sometimes a late-night raid of another cabin. When I was 12 years old, in tzrif 10, we did late-night cardio for three days in preparation for a raid on the kitchen. The staff had it all drawn up: Squad Aleph would go in first to see if the coast was clear, then Squad Bet would follow in and snag boxes of Hershey’s and Fruit Rollups. Everything went according to plan until the return trip, when we looked behind us and saw Brandon, the head cook, sprinting after us and shouting swear words none of us had ever heard before. “Quick, back to tzrif 8!” Our counselor yelled, as we made our way back to tzrif 10 under the darkness of the new moon.

Tzrif 8 didn’t get dessert for a week afterward.

I was a judge for color wars in 2012. For reasons way too complicated to explain here, I wore an eyepatch and bald cap all day. Photo: Jonathan Edelman

That was also the year that the winner of color wars was revealed on the pavilion overlooking the lake. Earlier that day, I had volunteered to play goalie for the red team’s floor hockey squad (no one else wanted to do it, because the pads and helmet were missing). Somehow, I held the other team to a shutout. Before the game, none of the kids knew who I was. After I helped the team win, they said I was great, and gave me high fives, and I was so happy I could barely feel my bruises.

Leading up to the announcement of the winner, everyone was cheering like crazy, believing that a last gasp of ruach would provide the points necessary to put their team over the top. It got so loud that other people who lived on the lake called in a noise complaint to the sheriff. The camp director finally got us to quiet down, but pretty soon we were up on our feet cheering again.

Two weeks earlier, I had been my “school self”: A reserved, awkward kid who felt like I didn’t quite fit in. And here I was, a valued part of a team, a full member of a community, cheering in Hebrew on a campground that had at one point been a Gentiles-only resort. My cheers this time were about the red team, but when the winner was announced (blue), all the cheers coalesced and crescendoed into a cheer for Herzl Camp. All cheers are about being part this group or that, but they all really say the same thing: We are here. We are alive. We are special. We have pride. And we are never going away.

Very rarely, though, that sense of unity fails to coalesce. It had happened the previous summer, when I was in tzrif Aleph with Stanley (which is not his real name). Stanley didn’t return to camp the summer of my great floor hockey triumph, which was in no way a surprise. He was overweight, unathletic, allergic to everything, a loud snorer, a bedwetter, and constantly homesick. Once, it was his turn to go to the kitchen and bring food to the table, and on the way back, he tripped and spilled chili all over himself, somehow fulfilling the definition of a schlemiel and a schlimazel simultaneously. And so we pounced, picking at his insecurities with the incisive sociopathy that only a child can muster—me most of all, because I was scared that if the others didn’t go after him, they would go after me. Stanley cried himself to sleep most nights. I was the only one from that cabin who attended Herzl the next year. I think that year was an anomaly—I never personally witnessed bullying for the rest of my time as a camper, and only once as a counselor. But that obviously didn’t make a difference for Stanley.

A lot of the personal growth that occurs at camp is a result of the relative lack of supervision, certainly when compared to the classroom environment. You have to solve many of your personal problems yourself, and figure out how to navigate complex social situations. Most kids rise to that bar, maturing in the process. But others take advantage of that freedom and use it against others. My two younger brothers followed me to Herzl Camp, and they both left because of bullying. One transferred to a different Jewish camp, which he still goes to and loves. The other withdrew from organized Jewish life entirely, until, after much begging on my part, he came back to work with me on staff my last summer, where he was absolutely incredible with the quieter, socially awkward kids. Working closely together with him greatly improved our relationship, which made it all the more depressing that we didn’t get to spend more years at camp together in the first place.

Even though things ended up working out well for my brothers (something that I can’t say for Stanley—I haven’t been able to track him down), I wonder if things would have been different if they had all stuck it out one more year. When I was on staff, I had a camper who had to be sent home because, among other things, he kept beating up other kids. The next year he came back, a year older and more mature, and was an absolute mensch, a really good kid. If my brothers had come back for another year, would they have found that their tormentors had become different people?

In terms of structural integrity, the basement of the dining hall is the safest place in Burnett County —underground, no windows, reinforced with concrete. I’ve always felt that this was a metaphor for something, that Herzl is a safe space where people can share secrets in strict confidentiality and try on new identities without getting mocked. This was definitely true in my experience, and the experience of most people I know—I’ve shared things with my closest camp friends that I’ve never told anyone else. But it always haunts me that Stanley and my brothers never got to feel that, as I did. I’d like to think that had they continued to attend as campers, the one bad summer would have slowly melted into the mists of memory, as they and their peers—their friends?—got older and more mature, gained more freedom and responsibility, and forgave each other for their childish cruelty. Maybe they’d have enjoyed Herzl Camp as much as I did.

And man, did I enjoy it. I can’t even recall ever thinking to myself “Wow, this is fun,” because pure contentment was my default state. Playing “roof-ball” and “500” and endless late-night card games. All of camp singing together during Friday night song session: Arik Einstein and James Taylor, Debbie Friedman and Cat Stevens. Laughing twice at each joke in the Saturday night comedy revue, once because everyone else was laughing, and a second time because you finally get the joke yourself. Even the educational programming was moderately enjoyable, certainly far more creative and interactive than most classes at the Jewish Day School. And if anything, the joy increased when I was on staff, because I was privileged to see that my work and planning made my campers happy and helped them grow, the same way my counselors did for me.

There’s definitely something to be said for the efficacy of Jewish camp. Even controlling for things like prior levels of religious practice and education, surveys show that kids who attend Jewish summer camps are 55 percent more likely to “feel very emotionally attached to Israel.” They are 45 percent more likely to attend a synagogue monthly or more when they grow up, and 30 percent more likely to give to a Jewish federation. Kids who attend Jewish camps take the skills that they learn and apply them as leaders of their local communities. Kids who attend Jewish summer camp, in other words, grow up as proud, visible Jews.

It’s such a loaded word that Weiss used, “indoctrination.” The lessons you’re taught (or not taught) in school, the values your parents work to instill in you, even the movies you watch: it all affects who you are and how you see the world. We’re all products of our environment, and as we grow older, we have to analyze all that we’ve been taught and decide what still makes sense and what we’ve grown out of. To say that I was “indoctrinated” denies the power of my conscious choice, as an adult, to shape my own moral philosophy, one that led me to conclude that returning to work at Herzl Camp was one of the best things I could do with my time.

The Herzl Camp alums I know hold incredibly diverse views of every signifier of American Jewish identity. One counselor, one of the worst I ever worked with, became ba’al tshuva, and made aliyah. Another, one of the best I ever worked with, is an atheist in a long-term relationship with a non-Jew. I’ve worked on staff with AIPAC campus activists and former Israeli soldiers, but also with someone who gave the most eloquent denunciation of the Occupation I’ve ever heard. There’s another guy who, last I heard, was selling chickens on a farm in rural Kenya. What do they all have in common? Though they all express it to highly varying degrees of religious observance, they’re all incredibly proud to be Jewish; and in their own way, they all love Israel, and want it to be its best possible self.

Here was our indoctrination: During breakfast, the music playlist mixed Hadag Nachash with One Direction. Hebrew words were sprinkled into everyday conversation—tzrif, ruach, kinuach, chugim. There was an Escape to Israel program, teaching us about Europeans Jews seeking religious freedom, where we had to make our way from a “detention camp in Cyprus” to “Tel Aviv” without being detected by the “British guards.” The older campers had mock parliamentary debates, where they were split into groups based on the real Israeli political parties, given a list of the party’s views on key issues and their demands for Cabinet positions, and were tasked with forming a governing coalition. The campers had to put themselves in the shoes of people they thought they could never identify with: Arabs, Haredim, hardline settlers, Shalom Achshav activists. By far my favorite program I helped create was a game show called “Israeli City or Pokémon?” (Flareon is a Pokémon. Holon is a city. Aggron is a Pokémon. Agron is a street in Jerusalem, not a city—trick question)

The goal was not to suggest that Israel’s policies are always right. The goal was to show that Israel is. It is a real place with real people and a culture all its own. It has a real history, one that is central to (but not exclusively) the story of the Jewish people.

The most purely Zionistic thing about Herzl Camp was not that it taught campers Israeli geography or the Shacharit prayers, but that it instilled pride. Pride in being an American Jew. Pride in the accomplishments of those who built a new nation and work to improve it today. Pride in getting third place in color wars because you gave it your all and that’s all anyone can ask. Pride in being a member of the Herzl Camp community, one that has given the world great music and insightful political analysis, but also untold numbers of doctors and accountants and construction workers, mothers and fathers who have built and maintained thriving Jewish communities in the last places most people would ever expect—Kansas City, Omaha, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Des Moines—and have passed their heritage on to their children. The reason some of today’s anti-Zionists don’t like Jewish summer camps is, perhaps, that deep down they aren’t comfortable with the idea of a strong and proud Jewish identity at all, and therefore, this anti-Zionism is really a form of anti-Semitism.

My favorite memory from being on staff at Herzl Camp wasn’t performing in the comedy show, or goofing around with my friends after the campers went to sleep. It was sitting in the basement and leading a series of discussions with eighty-something Jewish high school students about what they thought it meant to be a “Jewish leader.” I was blown away by their wisdom and maturity. Some of them went to Jewish Day School, others lived in small towns where they were the only Jews, coloring their perspective on how to express their Jewish identity. Every point on the “American Jew/Jewish American” spectrum was debated and defended. At one point, the conversation meandered to Israel, as it always does eventually. One kid was practically a Kahanist. Another proposed a binational state. Most campers fell within the two-state spectrum that is shared by a vast majority of American Jews, which is where the camp implicitly placed itself as well (the maps camp used were very consciously chosen—the big woodcut Israeli map near the flag circle has very conspicuous outlines of the pre-1967 borders). We’d often end our conversations with more questions than answers. But what could be more Jewish than that? There were always lots of disagreements, but all that mattered was that by the end, they felt a stake in the future of the Jewish people. At least, I’d like to think they did. The sad beauty of being a camp counselor is that you’ll likely never know if you were successful or not.

Most of my closest friends are going back to camp this summer, one last hurrah on staff before they join the “real world.” Some of my old campers are going to be on staff as well. I won’t be joining them: I already have a full-time job, one that pays significantly better than working at a summer camp, and I doubt my boss will let me take two months off (though feel free to read this as a 4,000-word request for vacation time).

I’d like to think that I’ll at least be able to go up for one last Shabbat, to make it an even 50. I can close my eyes and picture it now. Shabbat services will have the same tunes, and most of the songs we’ll sing during the song session will be familiar ones. I’ll have to quickly pick up the new cheers, of course. But whether I’ll cheer for a specific cabin, or a former camper who’s now on staff, or the glories of eating burnt potato latkes, I’ll really be saying the same thing, which is the essence of Zionism, the essence of Judaism:

We are here. We are alive. We are special. We have pride. And we are never going away.

![]()

Banner Photo: Noah Levinson