The expulsion of Jews from Arab countries, one of the biggest humanitarian crises of the 20th century, is all the more tragic for how little it is recognized today.

Palestinians and the various activists and organizations that identify with them marked “Nakba Day” on May 15.

This day commemorates what the Palestinians consider a national “catastrophe”—the establishment of the State of Israel. Among the most prominent issues addressed were the fates of Palestinian refugees. It is almost universally believed that there can be no solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict without a solution to the Palestinian refugee problem.

But there is another side to this problem, one that is rarely discussed and all but completely unrecognized by the international community: The Jewish refugees from the Arab nations.

No one can deny the Palestinian refugee problem, but it is equally blind to deny the plight of the Jewish refugees. With the creation of the State of Israel and in the decades afterwards, hundreds of thousands of Jews who had lived peacefully in the Arab nations for centuries were expelled from their home countries. Having failed in 1948 to destroy the new State of Israel, Arab rulers took revenge on the Jews who lived in the nations they controlled. These Jews, faced with official persecution, mob violence, pogroms, and the confiscation of their property, fled these countries, most of them to Israel. To this day, they remain mostly unrecognized and have never been compensated for their suffering or their stolen property.

It is time that this changed, because without recognition of the Jewish refugees from Arab nations, there can be no mutual recognition of shared suffering and thus no peace between Arabs and Jews. The Jewish refugees will not forgo their rights and their grievances while the Palestinians demand the same.

I know this better than most, because I am one of them.

When the issue of Jewish refugees from Arab lands is mentioned, which is rare, it is usually done in the context of Palestinian refugees. That is, the Jewish and Palestinian refugees are seen as analogous—in effect, a kind of reciprocal transfer of populations.

But this is inaccurate. In fact, the hundreds of thousands of Jews who fled the Arab lands were forced to abandon their countries out of fear for their lives. They had never taken any action against the countries against which they lived and had now malicious designs upon them. The Palestinians, on the other hand, had launched a war against their Jewish neighbors and made no bones about their desire to destroy the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine—the yishuv.

Moreover, a large portion of the Palestinian refugees left their homes voluntarily, convinced they could return after the invading Arab armies had eliminated the Jews. Kenneth Bilby, an American writer who worked in then-Palestine at the time, wrote in his book New Star in the Near East:

The Arab exodus, initially at least, was encouraged by many Arab leaders such as Haj Amin el Husseini, the exiled pro-Nazi Mufti of Jerusalem, and by the Arab Higher Committee for Palestine. … They viewed the first waves of Arab setbacks as merely transitory. Let the Palestine Arabs flee into neighboring countries. It would serve to arouse the other Arab peoples to greater effort, and when the Arab invasion struck, the Palestinians could return to their homes and be compensated with the property of Jews driven into the sea.

As early as February 19, 1949, the Jordanian newspaper Palestine wrote: “The Arab states encouraged the Arabs of Palestine to leave their homes temporarily so they would not interfere with the Arab invasion forces.”

It is also worth asking what would have happened to the Jews of Palestine if the Arabs had won their war. The answer can be seen in the statements of Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri Said: “We will blow up the land with our cannons and erase every remaining place the Jews take refuge. The Arabs must lead their wives and children to safe places until the end of the hostilities.” Arab League General Secretary Azzam Facha promised the Arab peoples that the conquest of Palestine would be a cakewalk. All the millions spent by the Jews on land and economic development would be easy plunder, he stated, because it would be a simple matter to throw the Jews into the Mediterranean.

The Jews of the Arab nations had no such intentions against their own countries, nor were they remotely capable of carrying them out if they had. They were small, peaceful communities, loyal to the ruling governments, and concerned with their own well-being and prosperity, much like the Jews of America today. They were not expelled because of anything they had done. They were expelled because they were Jews.

Most people are unaware of the size and scope of the Jewish refugee problem. In both human and economic terms, the expulsion was massive. Approximately 900,000 Jews fled Arab countries. Their property, confiscated or stolen outright by the Arab states—in particular Egypt and Iraq—is valued today in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Among these assets were the buildings that housed Jewish institutions, synagogues, factories, and personal property.

The losses were particularly heavy for the Jews of Egypt. For them, the persecution came swiftly. When Israel was established, the Egyptian government announced that the property of anyone whose actions were deemed dangerous to the state would be confiscated. This law was aimed at the Jews, who were collectively accused of supporting Zionism. Hundreds of Jewish businesses were confiscated. Their owners were sent to prison on charges of colluding with Zionism. After a year and a half, they were expelled with their families, most of them with nothing more than the clothes on their backs.

In 1954, the pan-Arab dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser rose to power in Egypt. State harassment of the Jews and official Jewish institutions quickly intensified. Jewish schools, hospitals, and welfare and youth organizations were nationalized or outlawed. Following the Sinai War in 1956, a second wave of persecution and mass imprisonment began. Approximately 35,000 Jews accused of Zionism were expelled with a few days warning. The government then issued a special decree that confiscated all Jewish property. Those expelled had their passports nullified and were forced to sign a declaration that they had no claims on Egypt and would never return to it.

At the end of 1956, Shlomo Cohen-Zidon, the vice-chairman of a federation of Egyptian immigrants in Israel, asked then-Finance Minister Levi Eshkol for help documenting the property that had been left behind by the Egyptian exiles. Eshkol agreed. In March 1957, a committee led by Cohen-Zidon was convened. It worked for worked for a year and a half, and documented over 4,000 claims. The Israeli Justice Ministry would later document a further 3,000.

After the Six-Day War in 1967, a third wave of persecution took place in Egypt, accompanied by the imprisonment of all Jewish men and the confiscation of their property. This proved the last straw, and almost the entire Egyptian Jewish community, dating back thousands of years before the advent of Islam, took flight. The amount of Jewish private and public property stolen by Egypt is estimated today in the tens of billions of dollars, with some claiming that the number is in the hundreds of billions.

Along with the Jews of Egypt, the Jews of Iraq were hardest hit by the waves of persecution that swept the Arab world after 1948. In the 1950s, the Iraqi government allowed its Jews to leave the country on the condition that they renounce their citizenship and their property. This resulted in several massive waves of aliyah, whereby most of the community was brought to Israel—over 120,000 people. Under Baath party rule from 1968-1973, the Iraqi Jews suffered from harassment by the government, which did not allow them freedom of movement and confiscated their property. In 1969, a series of pogroms killed around 50 Jews. Following this, the entire community, dating back to the Babylonian exile, fled the country.

This pattern repeated itself throughout the Arab world. For years, the Jews of Syria were not permitted to leave. The Jews of Yemen, Libya, and other Arab states eventually fled under pressure from official persecution. Their property was, again, confiscated. During this time, the Jews of all the Arab countries were second-class citizens. The governments invariably saw them as a fifth columnists. In places like Lebanon, apartheid laws were put in place denying the Jews government jobs. In short, life was made impossible for the Jews until, as was likely intended, they fled.

For decades, the plight of the Jewish refugees from Arab countries has been denied or ignored. Certainly, it has not received proper attention from the international media. Everyone talks about the Palestinian Nakba and the eternal rights of Palestinian refugees. No one talks about the suffering of the Jews of the Arab countries, the persecution and violence they faced, and certainly not their confiscated property.

But there is reason to hope that this is changing. In 2008, the U.S. Congress unanimously adopted a resolution recognizing the rights of Jewish refugees from Arab countries and saying that, if aid is given to Palestinian refugees, there should be similar aid and compensation for the Jewish refugees. The Canadian parliament had done the same in 2004.

Israel has also made the issue a priority. Two lobbies have recently been established in the Knesset that deal with the issue: One for the preservation of the culture and legacy of the Jews of Arab and Islamic nations, and one for the return of confiscated Jewish property. In 2010, the Knesset adopted a law to protect the rights of Jewish refugees from Muslim countries to compensate for their stolen property. It explicitly placed the issue in the context of the peace process. More recently, the Knesset designated November 30 as “Jewish refugee day.”

These actions are heartening, because refugees and their descendants believe that it is not possible to make peace between Israel and the Palestinians while this issue is ignored. The fact that many do ignore it does not mean we have given up. We have a moral and legal obligation to demand compensation from the Arab nations for their crimes against us.

We must not forget the silent and silenced trauma of a people. In everything connected to the peace process, Israeli governments and the countries seeking to mediate negotiations must ensure that for any solution to the problem of the Palestinian refugees, any reference to recognition of the refugees, and the creation of any mechanisms for compensation, there must be reciprocity for Jewish refugees as well.

There may have been two Nakbas, but it must be noted that the Jewish Nakba is not only a story of catastrophe, it is also one of triumph over adversity. Even today, the Palestinian refugees and their descendants are considered refugees and receive aid from UNWRA. Every Palestinian child is recognized as a refugee and continues to be subsidized by the international community. The Palestinians refused to develop a new way of life, preferring to live in the illusion that someday they will be allowed to reenter Israel and overwhelm its Jewish population by sheer force of numbers. But the Jewish refugees from Arab nations succeeded in overcoming their difficulties. They came to Israel with little or nothing and built their homes here. Many of them became successful as doctors, engineers, and lawyers, while some have even been elected to the Knesset.

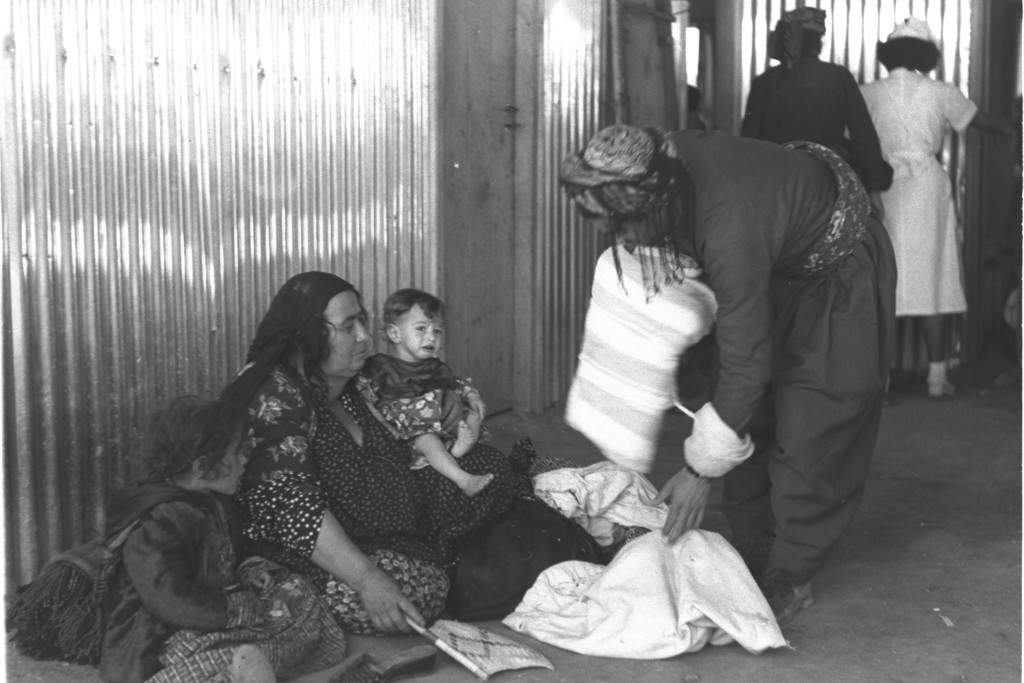

Nonetheless, the Jewish refugees should not be punished for their success. They had to overcome enormous difficulties to become part of Israeli society. The Jewish refugees arrived in Israel in a post-traumatic state. They did not talk about the past they had left behind. They were dispossessed and beaten down, and forged a life through an arduous process of survival. Most of them became part of larger society and made an extraordinary contribution to the state. But others, because their wealth and property had been stolen from them, remained mired in poverty on the periphery of Israel.

For them and their descendants, it is incumbent on the Western world to acknowledge that there were two Nakbas, two tragedies: The tragedy of the Palestinian refugees and the tragedy of the Jews from Arab nations.

The nature of aliyah from the Arab countries was diverse. Some chose to come to Israel out of Zionist convictions, but others did not. My family was one of the latter. We were third-generation residents of Lebanon, an inseparable part of Wadi Abu Jamil Street in the Beirut Jewish neighborhood of Harat Elihud. We did not want to leave. Over the years, we came to Israel for family visits, but always returned to our home in Lebanon. At that time, we were part of a community that numbered 7,000 in the 1970s.

Slowly, however, our situation became impossible. The rise of Hezbollah on one side and the weakness of the Lebanese government on the other left the Jews exposed to the same persecution our brothers and sisters had suffered before us. Slowly life became impossible. We became refugees, as defined in international law: someone who flees out of fear of persecution due to racial, religious, or national background.

We realized that this now applied to us in 1985, when Hezbollah kidnapped and murdered 12 Lebanese Jews.

Among them was my father, Haim Cohen, of blessed memory.

![]()

Banner Photo: Zoltan Kluger / Israel National Photo Archive / Wikimedia