The much-discussed Israeli cinematic documentary premiered this month in the United States. Made of amateur clips covering four decades of Zionism, it pretends to offer unvarnished “truth” while carving out an all-too-familiar, anti-heroic narrative.

It’s pretty easy to sum up the history of modern Israel: pioneers, Holocaust, independence, hope, war, disillusionment. At least that’s what the makers of the documentary film Israel: A Home Movie, a chronological collection of amateur footage shot between the 1930s and the 1970s, would have you believe.

The brainchild of Israeli filmmaker Arik Bernstein, the movie travels through major moments in the country’s formative past, viewing events such as the Declaration of Independence in 1948 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973 through the prism of these home videos, rewatched and narrated decades later by the footage’s owners.

The film reads like a Seurat painting. Viewed in isolation, the brush flecks that fill the image are colorful but mostly meaningless. When compiled, however, they tell a heartfelt, if slightly patchy, story of a nation trying to build itself from rubble.

But while on the surface, the film pieces together crucial moments of the state’s earliest decades, offering an explanation of how Israel became what it is today, the overall effect is denigrating and depressing—intentionally so. Israel, the main character in the home movie of its own life, is shown rapidly descending from the excitement of first-time experiences—“we were naïve” is the frequent refrain in the voiceovers—to the jaded tedium of middle age, looking back on its youth with a sense that potential was squandered and eyeing its future with trepidation for what likely awaits.

The trouble, however, is that this retrospective, weary personality isn’t any Israel that I know. Israel: A Home Movie it seems, is an eulogy for a country that’s far from dead—and a worn-out, somewhat stale critique of Israel as a story that never happened quite the way it should have.

One of the defining characteristics of Israel, the film’s director Eliav Lilti told me, is that people try to live their ordinary lives but are struck repeatedly by the historic events that surround them. “To me,” he said, “the country’s history is more interesting when it’s made out of the small stories of people who were – by accident – in all sorts of places.”

In an early scene of the movie, two young boys play in the dirt in a field strewn with plump oranges; one, wearing black slacks with a white shirt and tie, sits on his knees, while the other, in overalls and a red shirt, perches on a wooden crate. “He’s 70 now, that little boy,” a man’s voice says, although it’s unclear to which child he’s referring. The voice laughs but is tinged blue with nostalgia. In the next shot, a grinning boy in shorts jaunts towards the camera, swinging his arms as he walks. “Our brother,” explains the voiceover, female this time. “He was murdered by Arabs. He never got up again.”

In their smiling childhood, nothing obvious differentiates these boys. They each constitute three and a half chubby feet of potential. But, with time, fate sends them hurtling in different directions; half a century later, one is an old man and one is dead. Looking at the barelegged youths, it’s hard to say whose outcome is more surprising.

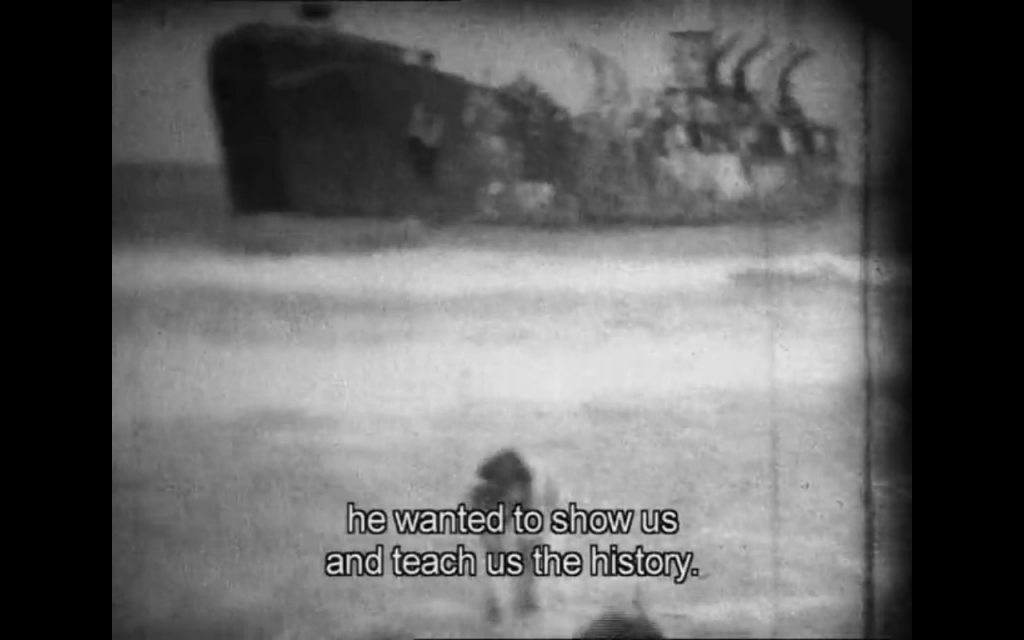

In another scene, Tzfira Eyal quite literally dances in the shadow of history. She plays in the sand on Tel Aviv beach, just meters away from where the Altalena – the ship carrying weapons for the Irgun that sunk in flames after being shot at by the IDF – lies half submerged in the frothy waves. In the voiceover, she argues with her sister about whether they went to the beach in order to learn about their history or just to enjoy the waves.

This idea, of grand history intervening in efforts to just live ordinary life, is perhaps most strikingly represented in a scene of footage filmed on a Saturday in October 1973, when Moshe Shargal and seven of his friends took a day trip to the beach along the coast of the Sinai Peninsula, which had been under Israeli control since 1967. They record each other larking about on the sand and diving into the waves, turning the camera to the sky to capture birds soaring above. Suddenly, two fighter jets fly into view, and Shargal films an Israeli Phantom firing at an Egyptian MiG. Engulfed in flames, the MiG tumbles into the sea. “We realized something was happening,” Shargal says over the footage, but he recalls that they thought about staying on the beach a little longer with two leggy Swedish girls they had stumbled across. At the time, of course, he couldn’t have known that he had just filmed the air battle that started the Yom Kippur war.

The history that this movie reconstructs is punctuated with warfare, misery, and endless romantic and anti-romantic interactions between Arabs and Jews. But all along, the viewer is haunted by the sense that she is being shielded from a very different Israel, the one that doesn’t boil down to just a string of conflicts. What about the other parts of Israeli history – its first Nobel Prize winner (Shai Agnon, literature, 1966), or its first gay pride parade (Tel Aviv, 1993), or its first Olympic gold medalist (Gal Fridman, sailing, 2004)? What about the scientists, the writers, the economists, the musicians, the chefs? We see nothing of the vibrant, colorful Israel that thrives outside of, and independently to, the conflict. Where did that Israel, the modern Israel we see today, really come from?

The filmmakers limit themselves by making their film only out of amateur footage, and restrict themselves further by using material recorded only until the 1970s. If the entire timespan of the Israel in this movie is 40 years, then we’re now, in 2013, a lifetime away from when that story stops. This movie, one senses, doesn’t just look at history. Rather, it is itself stuck in the past.

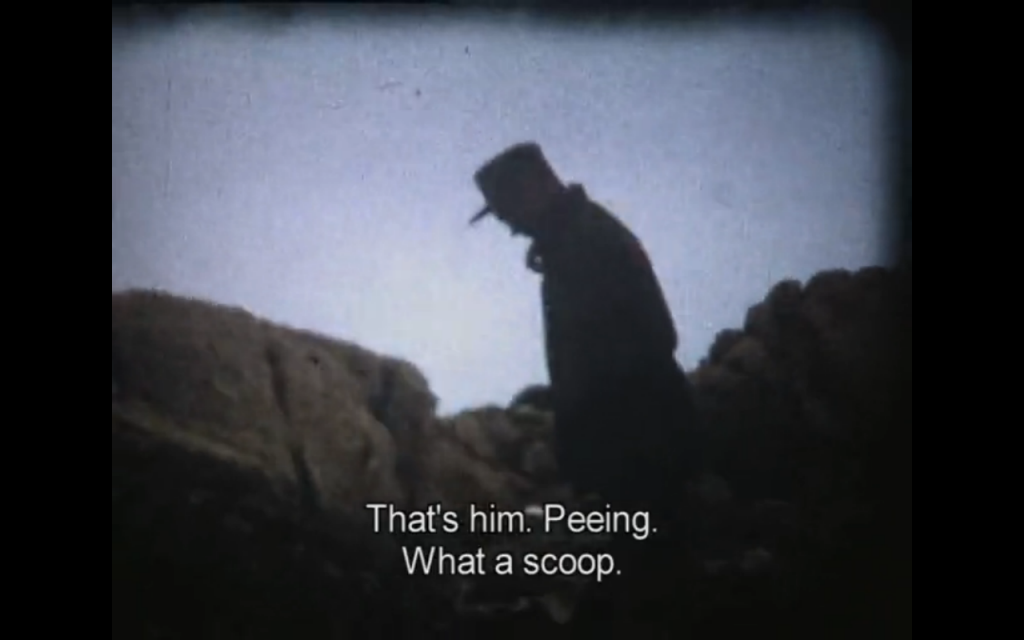

That’s not to say the film doesn’t capture a fascinating sliver of Israel’s history. In fact, it often succeeds in touching on our pre-existing collective memories. We discover, for example, previously unseen footage of the well-known politician Moshe Dayan, filmed by his son Udi. As Udi says in the movie, his father “wasn’t a street name or anything” back then. At one point, Udi films his father urinating in a field atop Mt. Hermon, Israel’s highest peak in the Golan Heights, captured in the Six-Day War. “What a scoop,” he laughs, joking that the clip brings together “the eye of the country” – referring to Moshe Dayan’s trademark eye patch – and “the eyes of the country,” which became Mt. Hermon’s nickname for its strategic intelligence-gathering value as a surveillance station.

“It’s not that he is going out to record, or shoot some historic moment, because some editor told him to,” Bernstein told me, talking about the Israeli everyman rather than Udi Dayan specifically. “He just happened to be there.” By using these amateur clips to narrate their tale, Bernstein and Lilti aim to remove the political filter clouding the official story of Israel’s life. But that is not to say the image is any clearer – quite the opposite, in fact. In the end, our image of Dayan is no richer or wiser than it was before, only tainted.

A similar effect is felt in another scene that shows a grainy recording of a group of Jews demolishing the minaret of a mosque in Nes Ziona, which was a mixed Jewish-Arab settlement until the War of Independence in 1948. Commenting over the controversial footage, Tzfira Eyal and Edna Grobshtein disagree over what they’re seeing.

“I told you before – it’s not a holy site,” says Eyal. “What we did wasn’t illegal. The mosque is the holy part. The minaret is just a high place where they stand and call people to prayer.”

By way of explanation, she continues: “We have a family disagreement. She’s afraid that the Arabs who saw us demolish the minaret will come and use it as proof that we destroyed holy sites. We didn’t destroy it.”

“But it’s documented here,” Grobshtein replies.

It doesn’t matter. “My conscience is clear,” Eyal concludes. We feel horror at the moral denial and jaded naivete. But we also can’t help notice the intended effect.

The footage used throughout the movie, particularly when viewed without the added voiceover, illustrates this point even more. Like the events that have shaped the history of Israel, and the way these events have been understood by those who experience them, the images are shadowy. Layers of gray blend into each other; it’s often hard to tell what exactly the video is showing. Characters and scenery waver in and out focus, flickering between blurry frames that bleed into one another. There is a constant backdrop of white noise that sounds like the consuming crackle of flames.

Even when chronicled in a permanent medium such as film, history is not indisputable, and it’s far from set in stone. The details exist in memory, and memories change.

Towards the beginning of the film, a cacophony of voices crescendos as unremarkable images – a woman smoking as she reclines on stone steps, a toddler jumping on the beach – flash across the screen. “It’s hard to distinguish what I really remember,” admits one unnamed voice. Others chime in with, “It’s all in my head,” then, “What’s based on photos or other people’s stories?” then, “I don’t remember my mother being sad.” One even says, “I don’t remember anything.”

Others are not so candid about their capricious precious memories.

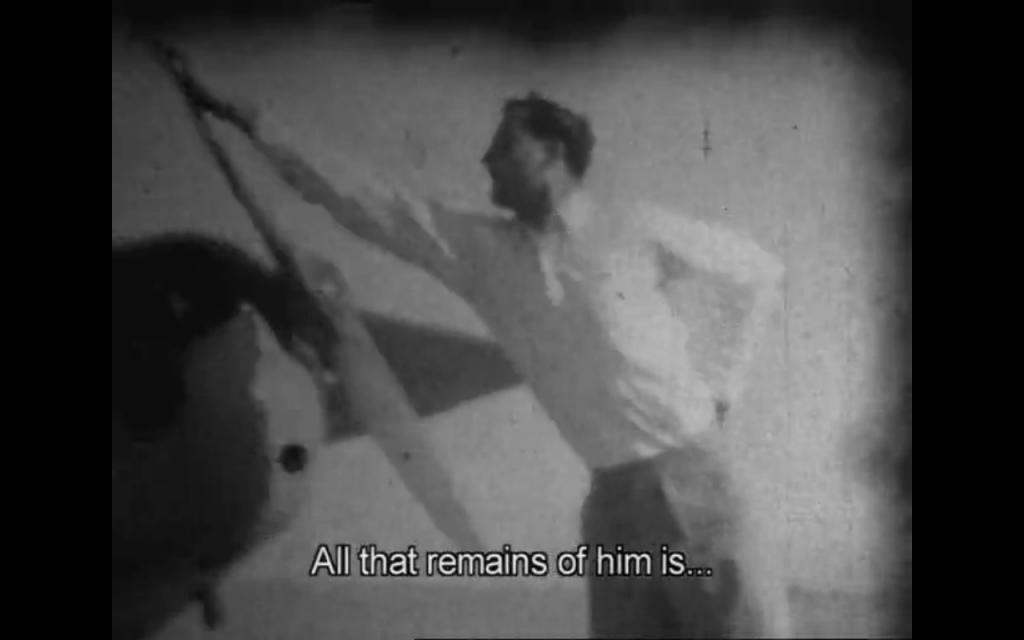

“Our brother Danny was a pilot,” says Shlomo Moussaieff, as the screen shows a tall man leaning forward to crank-start the propeller on his plane, the other hand resting on his hip. Danny was a member of the Palmach, the underground army in the years running up to independence in 1948. We find out he was killed on Radar Hill, near Jerusalem, after being missing in action for many years. “They never found his body,” Moussaieff says.

With his body gone, Danny exists only in these few seconds of footage and the memories of those who knew him. While Moussaieff recounts the story, the clip jerks repeatedly back to the beginning, its three-or-so second duration playing over and over again like an echoing memory that’s too slippery to grip onto properly. Moussaieff musters up his memories of Danny using the only shot of him that he has. “Danny,” we hear again “was a pilot.”

“All you have is this one image of Danny, and that’s the image he’s remembered by,” said Bernstein. Moussaieff might not remember the actual moment when Danny cranked that propeller, but he revisits the recollection through the home video, and the line between the image and the reality blurs. By repeating the quote and the clip over and over, however, the editors of the film create an effect that is very much the opposite of the sentiments originally expressed. Instead of pride, we hear in the older man’s voice something more like dementia.

Memories are not static snapshots, hovering eternally in a single moment of time gone by. They are whispers of the past that accompany us into the future. They morph with time – fading around the edges, intensifying in color or merging together – as we, and the world around us, change. Memories are unreliable.

It’s odd, therefore – ironic even – that ‘Israel: A Home Movie’ relies so heavily on other people’s memories to tell its story. What’s more, these people are old, and the memories they harbor are just as timeworn, which makes the revisited image pretty aged, too. And because the film cuts off in the late 1970s – the time when, according to the classic post-Zionist narrative, everything went wrong – the memories end up creating a barrier that prevents the movie from stepping into the present and touching upon the real Israel we know today.

Even unreliable memories can make for an interesting record. In the film’s coverage of the Six Day War, we watch footage of tanks rolling through the desert, black smoke billowing from a flame-ridden jeep and helicopters whirring through the air, and we hear memories from several people showing very different experiences of the same historical event.

“My worst wound was blisters on my feet,” says Benya Binnun, whose unit of paratroopers kept getting redeployed because the battles they were marching toward had been won before they arrived. But he is then interrupted by the cracked voice of Yael Babad recalling “horrific battles. We lost of a lot of men. You’d hear people screaming… another casualty, and another, and another.” Even the accepted facts are in dispute. “They say it lasted six days,” says Moshe Kiron, “but we were there the next day,” in Jerusalem.

And yet, with all these voices in ‘Israel: A Home Movie,’ comprising the personal history of the country, one is conspicuously absent: that of Israel’s Arabs. To be sure, Arabs feature throughout the film: from scenes from Nes Ziona, the pre-independence Arab-Jewish village where the mosque’s tower was destroyed, to later scenes in the settlement of Hebron. But at no point does the story become theirs.

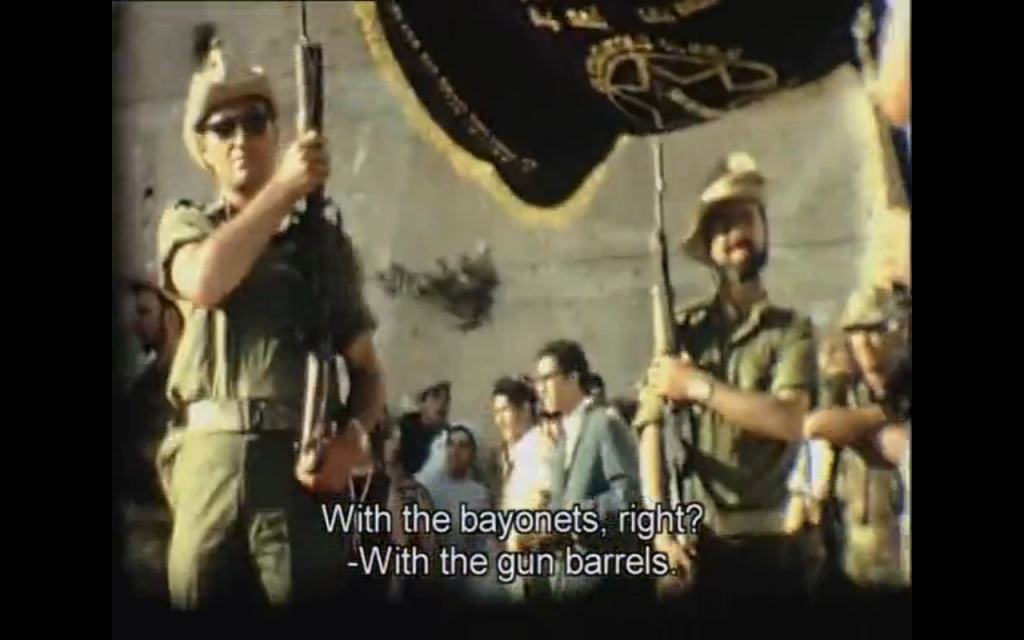

Miriam Lulu shares the tale of how she, alongside seven other couples, got married in 1967 in the first Israeli wedding to be held at the Cave of Machpelah since the State’s independence. In a scene pregnant with irony – a wedding staged in a mausoleum – the bride wears red while soldiers hold high the corners of the wedding canopy with the prongs of their fixed bayonets.

“The Arabs threw rice at us the whole way. It was a real celebration. The Arabs cheered and applauded,” says Lulu. “They were glad that the Jews took over.” When the camera pans over the Arabs in the crowd, however, they look rather more glum than gleeful, and there’s not a grain of rice in sight.

Similarly, in a clip filmed the following year, at the public march around Jerusalem marking the anniversary of the end of the Six Day War, Benya Binnun talks about the friendly relationships the Israelis had with the Palestinians as his voice, recorded in 1968, discusses whether the appropriate term is “liberated,” “conquered” or “occupied” territories. “The Arabs were very friendly – all smiles, welcome, greetings,” he says as he re-watches the video, recalling how they offered falafel to the marching Israelis. Meanwhile, the footage shows Palestinians sitting on chairs, massaging ritual beads through their fingers and watching with knitted brows as tens of thousands of Israelis parade through what had until recently been Arab land. And so, when a local Arab is given the opportunity to speak to Binnun’s camera on that same day in 1968, he paints quite a different picture: “I feel – because I am an Arab – very miserable, like a knife put in our heart.”

The lack of Arab voices in the movie isn’t for want of trying, the film’s creators said. Bernstein pointed to the limitations of using only amateur footage from the ‘30s to the ‘70s, when it was mostly middle and upper class people who were able to afford a camera.

Lilti added that Bernstein “really tried” to find footage of and by Arabs, but “no one was willing to cooperate. There wasn’t much material, but those that did have didn’t want to give it to an Israeli-funded project.”

In fact, the more one tries to understand ‘Israel: A Home Movie,’ the more the questions point away from the film segments, and toward the filmmakers themselves, both those who shot the originals and those who later curated them.

Some of the movie’s most arresting material belongs to Reuven Sela, who filmed a group of Israeli soldiers teasing and mistreating Egyptian prisoners of war. Stripped down to their loose white underpants and vests, the Egyptians are instructed to lie down on the floor and then jump to their feet in rapid and random succession. “You wouldn’t treat an animal that way,” says Sela as he rewatches the footage. “War turns men into beasts.” Yet in the video, Sela makes no effort to intervene in the humiliation he sees before him. “As an onlooker with a camera, I didn’t get involved. It wasn’t my place.”

Sela addresses one of the film’s key questions: what is our role as simultaneous viewer and participant in the historic events that unfold around us? He raises Bernstein’s theory, supported by numerous clips showing a different story from the one the narrator describes, that it’s not the person on screen who’s important, but the person holding the camera.

“That’s me,” says Roni Ninio, as he watches his 12-year-old self pace across the screen wielding a “very sophisticated” 8mm Canon over his shoulder like a gun, his finger poised on the trigger to shoot. Yet again, he is shown taking pride in his acumen as he films Palestinian refugees fleeing across the Allenby Bridge into Jordan.

But by the 1970s, explains Israeli TV host and one of the movie’s characters Meni Peer, the advent of television was elbowing home movies out of the picture and disempowering the individual from telling his or her own story.

“People who had Super 8 cameras suddenly felt small and unimportant in the face of the omnipotent electronic television,” says Peer. “As opposed to your personal, human, family footage… TV didn’t film the truth, it filmed a staged truth, and we, with our home movie cameras, we filmed the truth.” As he says this, an image lingers on screen of a messy-haired little girl sitting on the toilet. I see it as Bernstein’s version of the instruction famously attributed to Oliver Cromwell: “paint me as I am, warts and all.” Except it seems that Bernstein can’t see past the warts.

“We are manipulated by TV – there’s no doubt it decides our agenda,” said Lilti. When television found its way into every home, “we became passive and we let the state document our history for us.”

This movie is Bernstein and Lilti’s attempt to regain the conch from the state, to put the history of Israel back into the mouths of those who lived it. But there’s the rub. The film – which was, ironically, originally made as a three-part series for television – cannot pretend to present a narrative any more truthful, or less ideological, than the official history. While the movie has no script and no third party narrator, the final word always lies with the editor.

It’s clear from the outset that ‘Israel: A Home Movie’ is not a romantic saunter through the leafy gardens of Zionism. One of the opening scenes depicts a boat of dancing Jews arriving in Israel in 1930. After docking, people laden with bags and babies step off the boat and into the Promised Land, aided by smiling women with Stars of David on their uniforms. It’s just like a scene from a Leon Uris novel. But, once again, the voiceover tells a different story. An extract from the diary of one of the ship’s passengers, Samuel Yehudai, describes the unwelcoming reception he received at the port. The locals were sitting around eating lunch, he says, and no one even turned his head.

“I stood there like a fool. I felt so humiliated,” Yehudai wrote. “Imagine coming in and getting such a cold shoulder.” But he wasn’t totally ignored by everyone: “One guy called to me and wanted to give me some friendly advice. He said that if I had any money left, I should put it aside for the trip back.”

This disconnect between what we see on the screen and what the voiceover recounts – a device used so often throughout the film – is jarring. It’s the filmmakers’ way of undermining the Zionist narrative touted by ideological educators and politicians and suggesting that, with hindsight, the gold wasn’t that glittery after all. As one voice sums up, over footage of people dancing in a town square, “I don’t think it was as idyllic as it looks.”

So it’s not entirely fair for Bernstein to claim that his version of events is more honest and unbiased than any official record. The movie is drenched with his personal view, and it’s not particularly subtle.

“Well, the film does have an ideology,” he admitted. “It’s totally editorial for me to put it together… What we’re showing is an alternative way of storytelling, an alternative historiography. If you put together all these pieces of a diary over the 50 years that we’re dealing with, we don’t get the truth – but we get the DNA of many narratives formed together,” Bernstein said.

Lilti put forward a similar defense: “I didn’t make a national movie,” he said. “I didn’t make a political movie. It’s on the personal level.”

What the movie is really about, said Lilti, is the decay of youth – how those two boys frolicking innocently in the orange grove can grow up to be 70 years old, with little but a few grainy minutes of home video to preserve their young selves. “There’s something very sad about looking at yourself, young and beautiful, and it’s only a decaying memory,” Lilti said. This idea is expressed in the haunting Raquel Chalfi poem read at the end of the movie:

How does being depressed at 20 compare to taking a shower at 90?

How does going to bed with a woman at 21 compare to getting out of bed without a woman at 81?

How does getting drunk at 30 compare to drinking water without spilling it at 90?

How does getting a PhD in linguistics at 29 compare to getting a note from the stupid clerk at 74?

How does climbing the Himalayas at 26 compare to getting on a bus at 86?

How does running a meeting at 55 compare to taking a crap at 83?

How does listening to classical music at 32 compare to hearing a knock on the door at 82?

How does floating in meditation at 37 compare to standing up in a bathtub at 97?

How does writing this sitting down at 40 compare to reading it lying down at 90, and then trying to get up?

These thoughts on regret – on missed opportunities and moral mistakes – take on an added layer of melancholia when applied to Israel, a country that the filmmakers believe has repeatedly wasted, over the past few decades, the opportunity to forge peace and build a strong, sustainable future for itself.

But the film offers no alternative ending. Its feet are firmly rooted in the past – a past that it deems mostly unsavory – and its makes no attempt to find the spot where the sunshine falls, to bring the narrative into the present or to search for the place upon which it could build a more solid foundation for a stronger future.

Of course, the emotion most consistently portrayed is disappointment. There’s a recurring principle in the movie – a refrain, of sorts – of people emerging from war and believing they would now have peace. “We were sure it would be the last war,” a voice sighs. After the Six Day War, Binnun says: “We were sure that peace was coming soon.” After the Yom Kippur War, we are told, “There was a tremendous feeling that we could make peace.” And when Likud won the 1977 general election, Avinoam Tzabani remembers thinking that “suddenly there’s peace… I got goosebumps,” he says. “It gave you hope for a new life.”

That hope, according to the philosophy of ‘Israel: A Home Movie,’ is ebbing like the fading radiance of innocent youth.

“After every war, people said ‘now we will have peace.’ And every time, the situation deteriorates. It’s getting less and less possible to solve this conflict, and it’s very sad,” said Lilti. “When you see the film, you understand that this conflict could have been solved many years ago, when there was less hatred and less bloodshed and less pessimism. Now there’s theoretically a renewal of peace talks,” Lilti said, referring to John Kerry’s recent movements in the Middle East. Lilti laughed. “Nothing’s going to happen from it, I can assure you of that.”

Another figure encapsulates the poignancy of the situation when he asks, over footage of Arab families, “It’s a war over land, and war over land is forever. The question is, how do you turn the war into something you can live with?”

That’s the real message behind Bernstein and Lilti’s disjointed, anachronistic mosaic of the history of Israel. But to see Israel as little more than the sum of its dashed dreams – the collision of conflicting brushstrokes – is incomplete at best.

![]()

All photos: Screen captures from ‘Israel: A Home Movie’