My generation grew up with an Israel divided against itself. Now two great writers have tried to heal with words, and the results are deeply moving.

The modern state of Israel was born in the mind of an ecstatic playwright named Theodor Herzl. It was an idea, a story, and a drama long before it became the physical reality that it is today. Before it could be staged before a live audience, the story of a resurrected Jewish state had to be told and retold; and it is only through this storytelling that Israel became a reality. Those who founded Israel, built it, fought and sacrificed for it, did so because they were inspired by a grand idea and a magnificent story. They were the writers of their own epic drama.

From the beginning, the success of Zionism and Israel depended on the ability to tell a great story. The drama of the return of the biblical people to the biblical land moved Christians in Britain and across Europe to support the nascent Zionist movement. The story of constructing a perfect society from scratch sustained young pioneers in the difficult land of Israel, and attracted socialists and utopian thinkers of all kinds. The icon of the phoenix, of a nearly extinguished people reborn into new life of self-rule, inspired nations and peoples to rally to the cause of the newly established Jewish state.

These stories sustained Israel and Zionism over a century of struggle unparalleled in the history of any nation. But my generation has grown up wondering whether these stories are still relevant, still powerful, and still capable of motivating people to action. We came of age at a time when the foundational stories of Israel and Zionism were torn apart, revised, overturned, and attacked as illegitimate. Given the gift of individual freedom and choice, but bereft of a unifying story that gives meaning to those choices, we have been left to fend for ourselves. My generation celebrates an Israel that is diverse, fascinating, colorful, and messy; an Israel that acknowledges the many different views and perspectives of those who inhabit it. We do not want to return to a time when many were excluded in the name of unity. But we also mourn the loss of a grand, inspiring narrative.

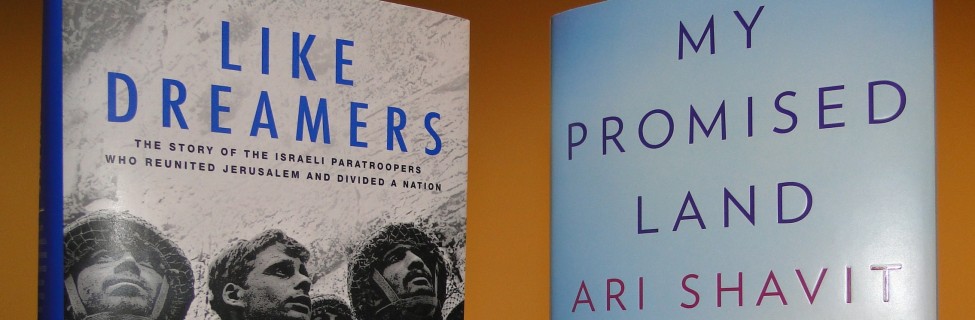

For Israel and Zionism to survive and thrive over the next one hundred years, a new story must be written and told; a single story that has room for all its characters and inspires all who hear it. Acclaimed Israeli writers Yossi Klein Halevi and Ari Shavit have attempted to do just that in their new books, Like Dreamers and My Promised Land, and though each approaches the task from a dramatically different angle, both of them succeed.

These are two very different books by two very different men. Interweaving the stories of a group of paratroopers who helped reunited Jerusalem in 1967, Halevi’s Like Dreamers traces the history of Israel and the divergent ideologies that shaped it from the Six-Day War to the present. Shavit’s My Promised Land takes a wider view, telling the story of the “triumph and tragedy” of modern Israel from early Zionism to the present day through a wide range of individual stories.

For both authors, Israel’s journey through the 20th century and into the 21st is also their own. Fourth-generation Israeli Ari Shavit and first-generation immigrant Yossi Klein Halevi are both deeply and profoundly Israeli, and so are their books. They struggle with what being Israeli means for them personally and how they fit in into Israeli society. Born only four years apart (Klein Halevi in 1953, Shavit in 1957), both men have embarked on writing their life’s work in order to resolve the question of their own personal identities. By telling the story of Israel through the lives of others, they are also struggling to decipher the meaning of Israel to their own lives.

Both authors begin with the mysterious entanglement of Jewish fear and Jewish power in modern Israel. Klein Halevi tells of his sense of dark foreboding as a young American youth following the events leading up to the Six-Day War. “My father and I shared the same unspoken thought: again. Barely two decades after the Holocaust, the Jews were facing destruction again. Once again, we were alone,” he writes. And then, as if to echo the sudden reversal of fate, immediately tells how “Israel reversed threat into unimagined victory.” His elation is still palpable all these years later as he describes how Israel “not merely survived, but reversed annihilation into a kind of redemption, awakened from our worst nightmare into our most extravagant dream.”

A Jewish settler struggles with an Israeli security officer during clashes that erupted as authorities evacuated the West Bank settlement outpost of Amona, February 1, 2006. Photo: Oded Balilty / AP / Knight Foundation / flickr

In the opening of My Promised Land, Shavit echoes Klein Halevi’s feeling of anxiety. He confesses that “for as long as I can remember, I remember fear. Existential fear.” But then, after detailing numerous instances of existential fear from 1967 on, he also confesses, “For as long as I can remember, I remember occupation,” recounting the manner in which Israel’s great victory turned “my nation” into an “occupying nation.”

Klein Halevi and Shavit are haunted by these reversals and extremes. They struggle to reconcile success and failure; triumph and tragedy; the pride and the shame that are Israel and Zionism. They both understand that the decade of reversals from 1967 to 1973 to 1977, and especially the trauma of 1973, “threw the Israeli psyche out of balance.” They both try to restore this balance through the personal. It is as if they have given up on any possibility of intellectually explaining Israel, Zionism, and the great revolutions of modern Jewish history. To them, Zionism and Israel are life, and just as human life is better told than explained, they try tell the story of Israel in the only way possible: Through its people.

Klein Halevi focuses on the stories of seven IDF paratroopers whose lives are so representative of Israel’s changes and struggles that they seem too good to be true. His protagonists are the kibbutzniks Arik Achmon, Udi Adiv, Meir Ariel, and Avital Geva; as well as the religious-Zionists Yoel Bin-Nun, Yisrael Harel, and Hanan Porat. These were the paratroopers who breached the gates of the Old City to become the first citizens of a sovereign Jewish state in two thousand years to stand on the Temple Mount and touch the stones of the Wailing Wall. They are the same paratroopers who, in an act of near-insanity, dared to cross the Suez Canal during the 1973 Yom Kippur War and turned it into Israel’s Stalingrad, turning the tide toward an Israeli victory.

Even though Klein Halevi himself admits that his protagonists belong to a very small and socially homogenous group—Ashkenazi men born in the 1940s—through the seven of them and their families and friends, he is able to chronicle the entire political, ideological, economic, and cultural spectrum of Israel: from Left-wing anti-Zionism to Right-wing messianic imperialism, high-flying capitalism to spartan socialism, militant atheism to religious dogmatism, Tel Aviv hedonism to yeshiva asceticism, avant-garde conceptual art to mystical Jewish poetry. He tells the tale of their ideological battles and their fraternity in war, of that which drove them apart and later brought them back together.

Klein Halevi’s protagonists, like their country, are not stagnant; they transform over time. They act upon their country and are acted upon by it. Yoel Bin-Nun, a Haifa-born yeshiva boy, was a “stubborn disciple” of the charismatic Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, helped found the settlement movement, and later broke with it in “grief and rage” following the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, his torment aiding in the country’s healing.

Udi Adiv, a member of Kibbutz Gan Shmuel, denounced “Israel’s plan for an imperialist war” against Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1967, broke with the far-Left Matzpen movement due to its support for a two-state solution, traveled to Damascus after the Munich Olympic massacre of 1972 to help the PLO create an anti-Zionist terrorist underground composed of Jewish and Arab Israeli, served twelve years in prison for it, completed his Ph.D. in London, and finally found himself back in Israel as a humdrum anti-Zionist academic—no longer so unique.

Yisrael Harel was born in 1939 in Central Europe, “the worst place and time for a Jew,” came to Israel as a refugee living among native-born Sabras and a religious boy in socialist, militantly secular Haifa. He longed from early childhood to be part of the “elite of sacrifice” and realized this dream by helping found the Movement for the Complete Land of Israel, organizing religious-Zionists and giving the movement a voice as editor and key writer of the settler journal Nekudah.

Meir Ariel, who drove a tractor in the cotton fields of Kibbutz Mishmarot and “distinguished himself in the paratroopers as a misfit,” achieved instant fame in 1967 after writing the anti-war song “Jerusalem of Iron,” but struggled for years to achieve recognition for his subsequent work and explored all modes of life and living. In Like Dreamers, he emerges as the Bob Dylan of his generation, giving voice to both anti-war cynicism and Jewish mysticism.

Hanan Porat established the first West Bank settlement in Kfar Etzion immediately after the Six-Day War and, after being wounded in the Yom Kippur War, went on to found the activist settler movement Gush Emunim—“Bloc of the Faithful”—with Yoel Ben-Nun and Yisrael Harel; but unwittingly found himself increasingly identified with the more extreme wing of the movement.

Avital Geva, the only one who remained a kibbutznik throughout, continued to insist on the relevance of socialism and, in the process of constantly searching for new ways to make it relevant to the younger generation, pushed his fellow kibbutzniks to think about their collective mission, and then (accidently) became a leading ecological conceptual artist.

Arik Achmon, who as a child tried his best to be “an exemplary kibbutznik,” ended up leaving his kibbutz as a young adult when his brand of Mapai socialism was denounced by the Stalinist majority. He then devoted his life to the military and becoming a hero of the Jewish people. Eventually, he broke with the “utopian nostalgia” of the kibbutz, seeking to introduce modern capitalism to Israel so that it might become the “great nation it could be.”

In telling the stories of these men, Klein Halevi achieves a remarkable feat. He writes a work of non-fiction that reads like a work of fiction. His storytelling is so skilled that the reader wonders whether Klein Halevi happens to be an extremely lucky storyteller, finding seven remarkable life stories that closely track the life of the nation, or whether he simply made it all up (he didn’t).

If Halevi tells the story of Israel by leading a chamber orchestra, Ari Shavit conducts a Wagnerian opera in seventeen acts, each one given a short title and date. “At First Sight, 1897” follows the journey of Shavit’s great grandfather to the Land of Israel. “Into the Valley, 1921” chronicles the passionate founding of the first major kibbutz. “Orange Grove, 1936” tells the story of Israel’s 1930s prosperity and the moment of Zionism’s “utopian bliss.” “Masada, 1942” deals with the forging of Zionism’s old-new myth of survival in the face of Arab attacks. The harrowing chapter on “Lydda, 1948” digs deep into a painful historical wound: The deportation of the city of Lydda’s Arab population during the War of Independence. Shavit’s rendering of the story is intense to the point that even the most indifferent reader will cry “enough!” “Housing Estate, 1957” tackles the creation of a new Israel out of huddled masses of poor refugees. “The Project, 1967” is about Israel’s nuclear program. “Settlement, 1975” deals with the settler movement. “Gaza Beach, 1991” relates Shavit’s own experience as a reserve soldier guarding jailed Palestinians. “Peace, 1993” tells the tragic history of Israel’s peaceniks. “J’accuse, 1999” grapples with the discontents of Israel’s Sephardi Jews. “Sex, Drugs, and the Israeli Condition, 2000” reports on Tel Aviv hedonism. “Up the Galilee, 2003” is concerned with Israel’s Arab citizens. “Reality Shock, 2006” chronicles Israel’s sense of impotence during the Second Lebanon War. “Occupy Rothschild, 2011” about Israeli innovation and industry. “Existential Challenge, 2013” about the nuclear threat from Iran. And finally, “By the Sea,” in which Shavit traces his great-grandfather’s journey through Israel and reflects on an alternative possible history for him and his family.

If Klein Halevi follows his protagonists wherever they go, even quite regular moments, Shavit calls his actors on stage to bellow grand and majestic arias. Some of the characters who appear are well-known, such as Shas party leader Aryeh Deri, who exemplifies “the oriental revolt” of Sephardi Jews; or Yossi Beilin, who personifies the rise and fall of the Israeli peace camp. But more frequently, it is lesser-known characters, such as Shavit’s great-grandfather and accidental Zionist Herbert Bentwich, or the forger of the modern Masada myth Shmaryahu Gutman, and even imagined characters like “the orange grower,” who tend to steal the show.

Among the lesser-known subjects are female Sephardi journalist Gal Gabai, whose pain is evident as she speaks of not quite belonging, of how even though “we have no other home, Israel is not quite home,” because Israel “was not really meant for us.” Due to the extermination of European Jewry, she says, “we were imported here and we were imported late.” And then there is the “ultimate Israeli” Kobi Richter, who never questioned whether or not he belonged, telling us, arrogantly but accurately, that “when Israel was about the kibbutz, I was on a kibbutz; and when Israel was about the military, I was in the military; and when Israel is about high-tech, I am in high-tech.” Indeed, he actually says of his service as one of Israel’s top fighter pilots, “It’s not that I played Tom Cruise; Tom Cruise played me.”

As the reader is introduced to more characters and more stories, each very different from the other, it becomes clear that Klein Halevi and Shavit have been driven to write by a very different kind of existential fear than the one with which they open their stories: The fear that internal schisms will lead to Israel’s demise.

Klein Halevi speaks of his father, who believed that “the great weakness of the Jews was the temptation of schism, even in the face of catastrophe.” Shavit writes of the seven “revolts” against early, spartan, activist Labor Zionism: The settler, peace, liberal-judicial, oriental, ultra-Orthodox, hedonist-individualistic, and Palestinian revolts. But while “each and every one of these upheavals was justified, the outcome of these seven revolts was the disintegration of the Israeli republic,” and from a certain point on “they became petty and dangerous.”

Their books are a desperate search for unity amidst the differences that are tearing Israeli society apart. They both deeply desire to achieve e pluribus unum—out of many, one. Klein Halevi’s father tells him that when the Jews are united “no enemy could destroy us.” Toward the end of his book, Shavit desperately asks, “Can 21st century Israel reconstruct the Mount Herzl republic?” and speaks of the “Herculean mission” to “unify a shredded society.”

Both Klein Halevi and Shavit write of these schisms in general terms, but it is clear that they are also deeply personal. Both have lived through the fraying of Israeli society. Both have witnessed in their own personal lives the ways in which Israeli society has been pulled and torn apart. They have lived through the age of unity of pre-1967 Israel, real or imagined, and watched in horror as it became fragmented and divided. They belong to the generation that witnessed firsthand Israel’s various “revolts,” and stood helpless when an Israeli prime minister was assassinated for his politics. Whereas my generation has grown up amidst these “revolts” with no memory of unity, except for the mythological one told though the nostalgic, rose-colored glasses of our parents, Klein Halevi and Shavit remember enough to seek to recreate it.

In their quest to forge unity from diversity and heal these schisms, Klein Halevi and Shavit wield the tools of their trade, the trade that has made Zionism and Israel possible—storytelling. But they tell their stories in very different ways. Klein Halevi’s storyteller is a quiet healer; Shavit’s is a fierce surgeon.

Klein Halevi writes his book in the soft light of dusk, when the setting sun bathes even the most dilapidated buildings in a warm glow. His sentences are soft and mellow, such as when he describes how the veterans of Kibbutz Ein Shemer trusted Avital Geva with the future of their community, “because he understood that without constant watering and pruning, this miracle conjured from the void would wither.” One can sense the pride of the old kibbutzniks as “they saw in Avital and his friends their own vindication. In a single generation—from Poland to Ein Shemer—the kibbutz had created young people who seemed to lack even a genetic memory of exile.”

Shavit’s book, however, is written in the harsh Israeli sun, under which all are exposed. Shavit’s phrases are full of sharp juxtapositions and contradictions. When describing the pioneers of Kibbutz Ein Harod, he describes their sense of urgency:

As Jewish Europe has no more hope, Jewish youth is all there is. It is the Jewish people’s last resort. Here it will be revealed whether the ambitious avant-garde is indeed leading its impoverished people to a promised land and a new horizon, or whether this encampment is just another hopeless bridgehead to yet another valley of death.

Even though Shavit is secular, his book reads like a Catholic confession—the story of a sinner who seeks salvation by speaking honestly and openly of his sins. Shavit is brutally honest throughout the book about the history of Zionism. He burrows mercilessly into its most painful wounds. He does so because after decades of struggle, he is seeking peace of mind and wants to restore balance to the Israeli psyche. Even though his book is about the stories of others, it is his personality that emerges throughout. In it, Shavit—whose public persona is one of seriousness, gravitas, and level-headedness—reveals himself as a tempestuous youth, fluctuating between euphoric highs and depressing lows. He is high on early Zionism, reveling in its triumphs, its utopianism, its youth, and its oozing sexiness. Even when Zionism turns brutal when faced with the Arab revolts of 1936-1939, one cannot mistake Shavit’s admiration for the “merciless determination” of those who forged a “community of combat,” realizing that it was about “us or them, life or death,” and whose spirit was “never to retreat, never to rest, always to push forward.”

But Shavit is also deeply anxious, even angry, about Israel and Zionism’s current condition. “Israel had become a state in chaos and a state of chaos,” he says. He is especially angry with the Israeli elite; the old ones who have “turned their back on the state they felt they had lost, and the new, rebelling forces never bothering to create a dedicated, meritocratic elite of their own.” And yet, as he confesses his sins, he still wants recognition for Zionism’s achievements and affirmation that not all is lost. He reminds us that “Zionism was about regenerating Jewish vitality,” and that “people that have come from death and were surrounded by death, nevertheless put up a spectacular spectacle of life.”

A woman argues with an IDF officer during the evacuation of Neve Dekalim, a settlement in the Gaza Strip, August 16, 2005. Photo: Israel Defense Forces / flickr

At the end of his confession, he still wants Israel and Israelis to be loved for who they are as they are. He tells the confessor that “we are not only creative and innovative, but authentic and direct and warm and genuine and sexy,” adding that “our grace is the semi-barbaric grace of the wild ones.”

If Shavit provides the confession, it is Klein Halevi who forgives. Although religious himself, Klein Halevi writes like a compassionate agnostic, accepting the grand impossibility of knowing anything for certain in this life. Even though the paratroopers are all his elders, Klein Halevi himself emerges from the book as the all-forgiving father whose wayward children have returned. They have travelled, they have strayed, but he does not judge the follies of their youth. He looks upon them with love and simply tells their stories so that their children, as Klein Halevi writes in the dedication to his own children, will be able to write “the next chapter.”

It is only through the prism of Klein Halevi’s compassionate confessor that both Udi Adiv’s decision to travel to Damascus to assist an anti-Zionist terrorist plot, and the messianic euphoria that accompanied the establishment of the settlement of Ofra right in the midst of Arab Samaria, can be understood in context. It is only when Klein Halevi tells how Hanan Porat—who as a four-year-old boy was forced out of his home and saw most of his childhood friends orphaned when his kibbutz, Kfar Etzion, was conquered by the Jordanian Arab legion and razed to the ground—returned after 1967 to rebuild the demolished community; that it becomes impossible to think of Porat as an “illegal settler.”

When Klein Halevi recounts the story of how Yoel Bin-Nun, who at the age of twelve confessed to a girl that his deepest longing was for “the Temple to be rebuilt”; was present at the age of 21 at the now-famous speech by Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook on the eve of the Six-Day War, in which the rabbi cried out against the Arab occupation of ancient Jewish sites such Jerusalem, Hebron, and Jericho; and then found himself one of the first Israelis to stand atop the Temple Mount a few short weeks later; even a committed atheist can understand why Bin-Nun saw the hand of God in the 1967 victory, and why he felt that “Jewish history had vindicated Jewish faith.” It is through Klein Halevi’s prism that one finds compassion for all Israelis struggling to make sense of the momentous events—sometimes lasting no more than a few days—that have marked their entire lives.

At the end of their stories, both tellers have told the story of Israel—and it is indeed one. Klein Halevi is the weaver at his machine, painstakingly creating a single cloth and pattern from the wildly divergent lives of his protagonists. Detail after detail, almost without noticing, a magnificent tapestry emerges on the other side. It is a picture that encompasses everyone, Left and Right, religious and secular, capitalist and socialist—a pattern in which Israel is “the partial fulfillment and partial failure of the contradictory dreams” of his protagonists.

Shavit, in contrast, creates one Israel by breaking it apart and laying bare its constituent parts for all to see. Beautiful and ugly, proud and shameful, black and white, no grays whatsoever, they shine in the glaring sun. And as the reader closes the book and takes a step back, a picture of one Israel emerges. One Israel where all parts belong, all parts make sense, and all parts are necessary. One Israel that “offers the intensity of life on the edge.”

Klein Halevi and Shavit are those rare beings who are lovers of Israel and defenders of Zionism, yet are not blind to the faults of the object of their affection. Through their stories they have given young Israelis the greatest gift: A story in which they can find themselves and of which they can be proud. And with that gift, a future can be built.

![]()

Banner Photo: Maxwell Woolley / The Tower