Why have so many pro-Palestinian activists been silent as the Syrian regime and its Russian allies butcher civilians? That’s a question that many other activists want answered.

In an interview with the socialist website New Politics in November 2014, Syrian dissident Yassin Al Haj Saleh was asked what the Western Left “could best do to show its solidarity with the Syrian revolution” against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. He replied,

I am afraid that it is too late for the leftists in the West to express any solidarity with the Syrians in their extremely hard struggle. What I always found astonishing in this regard is that mainstream Western leftists know almost nothing about Syria, its society, its regime, its people, its political economy, its contemporary history. Rarely have I found a useful piece of information or a genuinely creative idea in their analyses. My impression about this curious situation is that they simply do not see us; it is not about us at all. Syria is only an additional occasion for their old anti-imperialist tirades, never the living subject of the debate.

Saleh’s interview captured a general feeling of disaffection that is widespread on the Syrian revolutionary Left. It has resurfaced in recent months as the world watches the Assad regime’s horrifying demolition of the city of Aleppo. Syrians have waited in vain for the Western Left’s conscience to be pricked by Assad’s atrocities, but the chances that the Left would rouse itself on behalf of the Syrian people were always remote. The die had been cast in the Iraq War, from which the Left insisted on learning all the wrong lessons.

There had been a moment before Iraq when the anti-imperialist doctrines that animated the New Left during the Cold War were seriously reconsidered and sometimes repudiated. Ethnic cleansing and genocide in the former Yugoslavia persuaded many of the need for the doctrine that came to be known as Responsibility to Protect—military intervention in order to stop mass crimes against humanity. But the Left was divided on the matter even then, and opponents of Western military action paraded the same arguments they always did: The lack of UN authorization, the belief that what a barbarous regime did within its own borders was nobody’s business but its own, the certainty that America and NATO were pursuing some sinister but unspecified agenda, and so on and so forth. But in the end, the use of Western military power in the former Yugoslavia was broadly thought to have been necessary, ethical, and just.

Iraq changed all that. In this case, the invasion was widely perceived to have been unnecessary, unethical, and unjust—a war of choice conceived by ideologues and led by an American president the Left already held in contempt. The anti-war Left believed its views were confirmed by the failure to uncover a live WMD program or the promised stockpiles of chemical weapons. As Iraq slipped out of the occupation’s control and into bloody mayhem, the anti-imperialist axioms imperiled by the liberal interventionism of the ‘90s reasserted themselves. By the time the American troop surge and the 2006 Anbar Awakening succeeded in defeating al-Qaeda in Iraq and reducing violence to a fraction of what it had been, the anti-war Left hardly noticed. It believed the discussion was over: Intervention only made things worse, Bush and Blair belonged in The Hague, and the war’s dwindling band of defenders were instructed to observe a remorseful silence.

But the Syrian civil war has exposed something incoherent, dishonest, and ugly behind these left-wing pieties. It has demonstrated the terrible humanitarian costs of inaction, and about these, the leftists who once wept for Fallujah have had nothing to say.

This silence has confounded the activists and writers of the Syrian revolution. If the anti-war Left was moved to outrage by air-strikes in Gaza and Baghdad, why was it unmoved by the sight of Syrian bodies and buildings being smashed to atoms in Aleppo and Homs?

The Syrian revolutionaries’ confusion gave way to frustration that in turn gave way to anger, particularly when they noticed that what did galvanize protests was not a pitiless dictator smashing his fiefdom to smithereens, but any suggestion that the West might do something to stop him. When the Assad regime fired sarin gas into the Damascus suburb of Ghouta on August 21, 2013, killing hundreds of civilians, it looked for a moment as if the West, led by America, might finally intervene. It was only then that the anti-war movement lurched back to life.

Four days after the atrocity, the British writer and activist Owen Jones published an op-ed in The Independent passionately opposing military strikes against the regime “for the Syrians’ sake and for our own.” While Jones allowed that murdering people with chemical weapons was an “unforgiveable crime,” he devoted a full paragraph to casting doubt on Assad’s culpability. (This kind of atrocity agnosticism is a familiar and reprehensible anti-war maneuver.) A quick recapitulation of the West’s record in the region was enough to satisfy Jones that Western military power would only bring greater sorrow, and he found it “perplexing indeed” that the West should wish to become the “de facto allies of al-Qaeda.” As far as I can tell, the next time Jones wrote publicly about Syria was to oppose Western military action against ISIS two years later. “In Syria,” he hypocritically reminded readers of The Guardian, “civilians are overwhelmingly being killed not by ISIS, but rather by Bashar al-Assad’s regime and its indiscriminate barrel bombs.”

On August 31, 2013, ten days after the Ghouta attacks, Britain’s Stop the War Coalition held a rally in London. The veteran far-Left activist and writer Tariq Ali was introduced to the assembled crowd by the organization’s then-chair Jeremy Corbyn, now leader of the Labour Party. Corbyn called Ali “someone who has been leading the charge for a better world! A peaceful world! A just world! A world free of the yoke of imperialism!”

The Stop the War Coalition protests against British military action in Syria, November 28, 2015. Photo: Ben Windsor / flickr

Two days earlier, parliament had voted down a government motion recommending punitive military strikes against Assad. Ali responded with a post on the London Review of Books’s blog that began, “Rejoice. Rejoice. The first chain of vassaldom has been broken. They will repair it, no doubt, but let’s celebrate independence while it lasts. For the first time in fifty years, the House of Commons has voted against participating in an imperial war.”

Unlike Jones, Ali was not detained by even the pretense of concern for Syrian lives. The parliamentary vote, he exulted, was “like a shockwave,” but cautioned against premature celebration. France and America would not leave Assad unmolested, he warned, and so Stop the War’s noble work must continue. He called opposition to Assad “effectively a declaration of war against a sovereign independent Arab state!”, as if this should be enough to protect a dictator slaughtering human beings like livestock.

If Syrians were unimpressed by this bravura outpouring of solipsism and bombast, they were even less impressed to learn that Mother Superior Agnes Mariam de la Croix had been invited to speak at the Stop the War Coalition’s 2013 conference a few weeks later. A Catholic nun and regime propagandist, Mother Agnes was at that time vehemently insisting that video evidence of poison gas victims at Ghouta had been fabricated. This alone, wrote James Bloodworth in The Spectator, made her “at best a crackpot and at worst an apologist for one of Assad’s worst atrocities.” In the end, Ba’athism’s bride of Christ did not attend, but the advertised list of speakers is a sobering indication of Labour’s recent transformation into a parliamentary instrument of anti-war agitprop. Scheduled to speak alongside Mother Agnes were not only Corbyn, but also Diane Abbott, now the shadow home secretary, and Guardian commentator Seumas Milne, now the party’s Director of Strategy and Communications.

Hundreds of people gathered outside Downing Street October 22, 2015, to protest against the lack of Western action to secure a ceasefire in Aleppo or to prevent the continued bombing of civilians in East Aleppo by Russian and Syrian aircraft. Photo: Alisdare Hickson / flickr

Between these spikes in activity, anti-war writers at mainstream left-wing outlets like The Guardian, The Independent, The Nation, and Salon, as well as more radical sites like The Intercept, Electronic Intifada, Counterpunch, and MediaLens, kept leftist opposition to intervention alive. Their articles may have differed slightly in their particulars, but the fundamentals never changed, no matter how harrowing the images emerging from the Syrian maelstrom: Assad may be awful, but he is not as awful as warmongers say he is; the opposition is considerably more awful, and is dominated by al-Qaeda and ISIS; Iraq provides irrefutable evidence of American incompetence and mendacity; and the West should not lecture Russia or Iran (or anyone else for that matter) on human rights as long as its own allies include Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Of these writers, perhaps none disgraced himself with quite the dedication of The Independent’s aging Middle East expert-turned-Assadist stenographer Robert Fisk. Nodding and note-taking, Fisk stumbled around Syria in the company of a regime minder, filing stories of Assad’s valiant war on terror for consumption by the credulous and unwary. Syrian regime commander Gen. Ali Ahmad Asa’ad, Fisk informed his readers on July 5, 2016, “agrees that his soldiers open fire on their antagonists only if they are shot at.”

In a 2015 dispatch, Fisk mocked Western impotence in the Middle East and lavished praise on the humanity and efficiency of the Russian and Syrian armies. “The Syrians have found that the Russians do not want to fire at targets in built-up areas,” he reported solemnly. “They intend to leave burning hospitals and dead wedding parties to the Americans in Afghanistan.” With satisfaction, Fisk concluded that, “if it wins…the Syrian military is going to come out of this current war as the most ruthless, battle-trained and battle-hardened Arab army in the entire region. Woe betide any of its neighbors who forget this.” Arab writers and activists who once eagerly circulated Fisk’s lurid accounts of Western and Israeli wickedness have since taken to calling him an apologist for fascism.

But it is the ongoing strangulation and bombardment of Aleppo that has brought a new ferocity to intra-left feuding not seen since Ghouta. On August 17, 2016, the Australian journalist Sophie McNeill tweeted a short, distressing video of a shell-shocked little Syrian boy named Omran Daqneesh sitting in the back of an ambulance. His face and body still caked in blood and dust, he had been rescued from the remains of a building reduced to rubble by a Russian airstrike. “Watch this video from Aleppo tonight,” she tweeted. “And watch it again. And remind yourself that with #Syria #wecantsaywedidntknow.” Ali Abunimah, the pugnacious co-founder of the ferociously anti-Israel website Electronic Intifada, sent a tweet in reply that read, “Who is saying we don’t know? What exactly are you proposing? An Australian invasion of Syria?”

By its own standards of incendiary polemic, Electronic Intifada kept a relatively low profile on Syria, and this had already begun to raise eyebrows, not least among pro-Israel writers who detected a callous double-standard. But the unguarded contempt in Abunimah’s tweet revealed something telling. That his opinion had not even been solicited only made its scornful tone all the more gratuitous. Given the reckless cynicism with which Electronic Intifada has used images of dead children as an instrument of political activism, the hypocrisy was redolent. Beneath Abunimah’s irritation and indignation, there seemed to lurk a certain resentment that Syrians were usurping the Palestinians’ rightful claim to be the world’s most pressing human rights emergency.

As the row escalated, the left-wing blogosphere divided. Other writers at Electronic Intifada, Salon, and AlterNet who chimed in to support Abunimah’s opposition to a U.S.-enforced no-fly zone in Syria suddenly found their mailboxes and Twitter accounts filling up with furious accusations of treachery. British-Lebanese writer and activist Oz Katerji sent a series of private messages to Electronic Intifada blogger Rania Khalek praising her website’s work and beseeching her to reconsider her views. Khalek responded by publishing parts of the message as evidence of a campaign of harassment. “These people are shameful,” she later tweeted. “All they care about is trashing leftists.” Her Intifada colleagues followed suit, registering their own pitiable complaints of Twitter victimization. Then AlterNet’s Max Blumenthal inflamed the row still further with an endlessly long two-part would-be exposé of the Syrian opposition.

In part one, Blumenthal described a network of sinister groups, anonymous donors, wealthy exiles, government agencies, media dupes (including Sophie McNeill), and other interested parties conspiring to manipulate Western public opinion. Their goal, he claimed, was regime change in Syria, and Blumenthal argued that a no-fly zone would inevitably result in this apparently undesirable outcome. It was the usual boilerplate conspiracy theory, purporting to reveal that things are not as they appear, heavy on insinuation and ominous atmospherics, light on rigor and substance, and all informed by a generally adolescent misanthropy.

But in part two, Blumenthal sought to discredit the White Helmets, a volunteer group of citizen first-responders who risk death to rescue survivors of aerial bombardment. This second article generated considerable outrage. After all, 140 of the organization’s members had already been killed doing this perilous work. While Blumenthal conceded that the White Helmets do save lives—even if he wasted an unseemly paragraph quibbling over how many—he also accused them of being part of the interventionist plot he described in part one.

Max Blumenthal speaks at the New America Foundation, December 4, 2012. Photo: New America Foundation / flickr

Of his various allegations, the most toxic was that “members of the White Helmets have been implicated in atrocities carried out by jihadist rebel groups.” This staple of regime propaganda had already been circulated on social media by Tariq Ali on the far-left and Nick Griffin, former leader of the British National Party, on the far-right. Now Blumenthal was casually repeating it in a widely-read news outlet. Syrians and their supporters were appalled. To Abunimah’s evident consternation, 166 Palestinian activists co-signed an open letter affirming that they would “cease working with activists whom we once respected.”

It then emerged that Khalek had agreed to speak at a regime-sponsored conference in Damascus organized by Bashar al-Assad’s father-in-law, at which she was expected to denounce Western sanctions targeting the Assad regime. The Electronic Intifada found itself engulfed once more by waves of recrimination, and on October 30, Khalek sent out a tweet bitterly announcing her resignation. Abunimah’s Twitter feed lapsed into a brief and uncharacteristic silence, while other contributors to the site, past and present, scrambled to distance themselves from Khalek, driving speculation that her abrupt exit had not been entirely voluntary.

The activist Iyad el-Baghdadi spoke for many of the site’s erstwhile disciples when he lamented that the “Recent conduct of @intifada figures is a lesson for how you can build a strong activism brand, then destroy it in a few disastrous weeks.” This heroic bit of point-missing is perhaps understandable given the unattractive alternative—that the Syrian civil war has exposed something fundamentally corrupt in the anti-imperialist worldview, and that el-Baghdadi and thousands of other like-minded Leftists had spent their lives imbibing the propaganda of unscrupulous charlatans.

In fact, contrary to this narrative of betrayal, the anti-imperialist Left’s position on Syria has been perfectly consistent with its previous history. During the Cold War, the New Left considered capitalist democracy nothing more than a new kind of fascism disguised as freedom, while Zionism—in keeping with the Soviet anti-imperialist line—was a Western colonialist plot. Any regime, no matter how backward or barbaric, which opposed this twin threat was rewarded with reflexive sympathy, especially (but not exclusively) if that regime happened to be left-wing.

If the end of the Cold War robbed radicals of its preferred alternative to supposed Western tyranny, the objects of anti-imperialist hostility—the U.S., Israel, and the West in general—remained, empowered by a unipolar reality and still no better than its new theocratic and totalitarian enemies. And so, as dissidents around the world languished in dictators’ jails, Western radicals continued to inveigh against the imperfections of their own free societies. From the positions of comfort and influence they had by now acquired in academia and journalism, they denounced the West’s history, culture, politics, and foreign policy with a ferocious zeal and what they took to be uncommon courage.

One the most revered and influential of these voices belonged to Edward Said, a Palestinian-American professor of comparative literature at Columbia University. In late 2002, Said became involved in a public feud over Iraq that perfectly foreshadowed the Left’s current strife over Syria. Nine years earlier, and two years before the Balkans debate would be ignited in earnest by the Srebrenica massacre, an Iraqi exile named Kanan Makiya had published Cruelty and Silence. It was his second book about the nightmare that revolutionary Ba’athism had visited upon his native country, and an indictment of the anti-imperialist rhetoric and post-colonial theory that Makiya argued was betraying the victims of Middle Eastern totalitarianism.

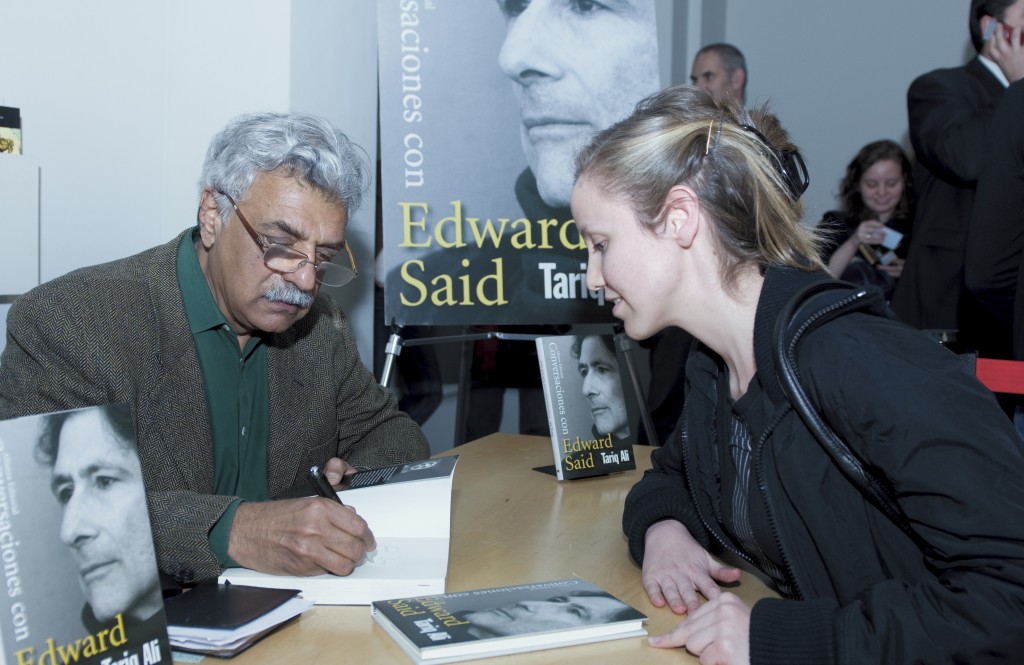

Tariq Ali signs a copy of his book Conversations with Edward Said in Cordoba, Spain. Photo: Fundación Córdoba Capital Europea de la Cultura / flickr

Arab intellectuals in particular, he wrote, had become so preoccupied with Orientalism, colonialism, Zionism, and American neo-imperialism that they seemed to forget Arabs were also political and moral agents. He catalogued the fantastical contortions these intellectuals underwent to persuade themselves and others that Saddam Hussein’s unprovoked invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 was either justifiable or America’s fault. In thrall to a cult of Middle Eastern victimhood and self-pity, which Makiya called “the greatest killer of solidarity with others that could possibly be invented,” they were engaged in a transfer of responsibility “away from the Ba’athi state of Iraq, where it so obviously lay, and on to the United States. In this exercise, those anti-war activists who acted out of an emotionally understandable but nonetheless knee-jerk opposition to anything the American state chose to do unwittingly played into the hands of the worst kind of despotism.”

Needless to say, the book was not especially well-received by those on the anti-imperialist Left who bothered to read it. Said was particularly scathing. Makiya had accused him of sowing “doubt on whether or not the Iraqi regime ever gassed its own Kurdish citizens.” Said responded by labeling Makiya a traitor to the Palestinian cause and suggesting that he held an essentialist (which is to say, racist) view of Arabs. The quarrel died down, not least because Said made it clear he considered Makiya to be a person of no consequence unworthy of his lofty attentions.

But a number of people on the Left read Makiya’s book, and his earlier monograph about Saddam’s Iraq, Republic of Fear, and decided he had a point. The effect was not unlike that produced by the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago in 1974. Just as Solzhenitsyn’s writing caused part of the New Left to finally acknowledge the full horror of Soviet communism, Makiya’s writing provided a rare window into the paranoid violence of Saddam Hussein’s brutal prison state. These books, and others like them, were part of an alternative anti-totalitarian tendency, dissenting from and at odds with the Left’s prevailing anti-imperialist orthodoxies.

By the winter of 2002, Makiya was serving on the Democratic Principles Working Group advising the U.S. State Department as America prepared to invade Iraq. That November, he published an essay in Prospect describing what he hoped to see emerge from the ashes of the Saddam Hussein regime. Said, suddenly aware that Makiya was not a peon to be brushed aside after all, responded with a vitriolic article in Al-Ahram Weekly which rose to a crescendo of ad hominem and hysterical malice:

In and of himself, Makiya is a passing phenomenon. He is, however, a symptom of several things at once. He represents the intellectual who serves power unquestioningly; the greater the power, the fewer doubts he has. He is a man of vanity who has no compassion, no demonstrable awareness of human suffering. With no stable principles or values, he is typical of the cynical anti-Arab hawks (like Richard Perle, Paul Wolfowitz, and Donald Rumsfeld) who dot the Bush administration like flies on a cake. British imperialism, Israel’s brutal occupation policies, or American arrogance do not detain him for a moment. Worst of all, he is a man of pretension and superficiality, flattering himself on his reasonableness even as he condemns his own people to more travail and more dislocation. Woe to Iraq!

I defy any fair-minded reader of Makiya’s compassionate writing on the Middle East to arrive at this conclusion. But this was not a disagreement over the wisdom or strategy of America’s Iraq policy; it was a collision of fundamentals. Said had always concentrated on a critique of Western power to the exclusion of almost everything else. If he felt that Makiya paid undue attention to “British imperialism, Israel’s brutal occupation policies, or American arrogance,” it was because his own ideological blinders admitted a view of nothing else. In his memoir, the late Christopher Hitchens would recall of his former friend,

Edward once surprising me by saying, and apropos of nothing: “Do you know something I have never done in my political career? I have never publicly criticized the Soviet Union. It’s not that I terribly sympathize with them or anything – it’s just that the Soviets have never done anything to harm me, or us.” At the time I thought this a rather naïve statement, even perhaps a slightly contemptible one. … It was only later to occur to me that Edward’s pronounced dislike of George Orwell was something to which I ought to have paid more attention.

In contrast to Said, Makiya attempted to understand Iraq as a product of Ba’athist ideology and systematic repression. In so doing, he was drawing upon the tradition of liberal anti-totalitarianism that Orwell exemplified and to which Makiya had come by way of Hannah Arendt. In this analysis, he was joined by former Eastern bloc dissidents like Václav Havel, Lech Wałęsa, and Adam Michnik, who had suffered the reality of communist oppression and who consequently lent their considerable moral authority to the cause of regime change in Iraq. Liberal democracy, they maintained, is not simply a veiled form of fascism, but its antithesis. Democratic accountability, a free press, universal human rights and protections, and the rule of law created an objectively superior system of emancipatory governance to which all people were entitled. It had to be defended where threatened and struggled for where thwarted.

But the fallout from Iraq had a catastrophic effect on what was already a fraught debate. Anti-imperialists who had marched against the war in the name of Iraqi human rights rejoiced at the humbling of American power and every bloody setback the democratic project in Iraq encountered. Under Barack Obama, America tilted back to a risk-averse and anti-interventionist foreign policy. The membership of the British Labour Party surrendered its leadership to Corbyn and the Stop the War Coalition in a fit of reckless enthusiasm. But the Middle East remained what it was, and so long as the pathologies identified by Makiya remained unaddressed, so did his arguments. And when those pathologies were unleashed in Syria in the wake of the Arab Spring, it became apparent that Iraq had in fact settled nothing.

Protesters at the Stop the War Coalition’s Stop Bombing Syria protest in London, December 12, 2015. Photo: Garry Knight / flickr

Today, as Syrian cities blaze, anti-imperialist writers continue to demand apologies from those who supported the liberation of Iraq, and react with jubilation to each new setback for intervention. The British former parliamentarian George Galloway, who once bent his knee before a genocidal Ba’athist tyrant in Baghdad, now appears on Iran’s Press TV to do the same before the genocidal Ba’athist tyrant in Damascus. Syrian exiles are ignored or denounced as collaborators with American imperialism just as Iraqi exiles were before them. Max Blumenthal and Electronic Intifada circulate lies about Syria in the service of a conspiratorial anti-Western narrative just as they have peddled lies about Israel in the service of that same narrative. Iran and Hezbollah and Assad are defended as an anti-imperialist “axis of resistance” to the Zionist entity. Russia’s actions are defended as a check on American power. And in the midst of all this mayhem, Iraqi and Syrian lives are no more than a talking point, and “democracy” nothing more than a cudgel with which to beat the West.

Anti-imperialism’s first and most serious error lies in the refusal to make a clear moral distinction between democracy and dictatorship, and therefore between liberty and tyranny. And in the blasted landscapes of Syria’s smashed population centers, the anti-imperialist Left’s professed concern for Arab life, which enjoyed such undeserved currency in the wake of Iraq, has finally been exposed as a squalid lie.

What divides the Left over Syria is what previously divided the Left over Iraq and the Balkans, and it is the anti-totalitarians, not the anti-imperialists, who have been the Syrian people’s most consistent advocates. The same coalition of liberal hawks and neoconservatives that supported the liberation of Iraq now support intervention in Syria for the same reasons. For activists hitherto nourished on an anti-imperialist worldview that holds the West responsible for all the world’s ills, this will take some getting used to. But by now it ought to be obvious that it is pointless to expect support for a democratic struggle from those who do not understand the value of democratic freedoms.

![]()

Banner Photo: Garry Knight / flickr