The Hebrew renaissance produced writers, fighters, painters, and prostitutes. Now it has its own non-Jewish literary hero. Sayed Kashua holds up a mirror to Israel, and spares no criticism for his Arab community as well.

In the story “Shem and Japheth on the Train” by the great Hebrew-Yiddish writer S.Y. Abramowitz, a pack of downtrodden Jews are crammed into a third-class train car as it hurtles through Bismarck-era Germany. Squeezed in among the poor and abject folk is our author, who refers to himself by his pen name, Mendele Mocher Seforim—Mendele the Book Peddler.

Across from Mendele sits a destitute family. “Their dress, their appearance, their wan expression, testified to extreme poverty and roused my pity,” Abramowitz writes. Suddenly Japheth, a cheerful Polish gentile, emerges from his hiding place. “His face was chalk-white,” Abramowitz tells us, “his cheeks sunken, and his mustache formed thin fringes whose ends dropped like lizards’ tails from the sides of his mouth.” What is he doing on a train packed with Jews?

Japheth proceeds to tell the fascinated Mendele that this family, and in particular its patriarch Reb Moshe the Tailor—referred to as “Shem”—have become his mentors. Japheth once enjoyed security and wealth. This luxury led him to arrogance and its sinister European cousin, anti-Semitism. Though he and Shem were once friends, after Japheth fell into the cult of hatred, he even participated in a pogrom. But when tyrants reign and societies unravel, no one is immune to the bitter consequences. History’s dark shadow soon swallowed up the Poles in addition to the Jews, and Japheth found himself as down-and-out as his Jewish neighbors. Faced, like the Jews, with banishment, Japheth asks Shem to teach him his ways. In essence, he asks not to become Jewish, but to learn to live like a Jew.

“Stay a Christian as you have always been, and keep your religion in your own way,” Shem tells Japheth, “but there is one thing you must learn to do. You must come to master the Jewish art of living, and cleave to that, if you are to preserve yourself and carry the yoke of exile.” And so Japheth learns to follow his Jewish brother, wandering the earth and bearing his lot like a Jew.

More than a century later, the Jews have fostered another Japheth, and this time, he is marked not by scarcity but by snark. Arab-Israeli writer and satirist Sayed Kashua has a weekly column in Haaretz, a wildly popular prime-time comedy on Israeli television, and three critically-acclaimed novels under his belt. And everything he has done, he has done in Hebrew. He is Japheth to today’s Israeli Shems, a gentile living among the chosen people, the outsider who has burrowed his way into the fold.

Sayed Kashua, says Dana Olmert, a literary theorist, editor, and daughter of former prime minister Ehud Olmert, “is really writing within this tradition of being an uprooted writer torn between tradition and identity. He’s no longer a part of the traditional Arab culture because he was raised and educated in Hebrew and in Jewish school. He’s Israeli more than anything else.”

The 37-year-old Kashua is a hard-drinking chain smoker, his baby face marked by bags under his eyes, and his speech often trails off into indecipherable muttering. In his weekly Haaretz column, Kashua exposes his persistent malaise, his deep-seated insecurity, and his fumbling struggles with fatherhood, married life, and professional ambition. Having learned to live among the Jews and adopt their ways, one wonders why Kashua isn’t as jolly as Abramowitz’s Japheth. Perhaps it’s because today’s writers must project a fuller, less allegorical picture than in the past; and Kashua is nothing if not a complex storyteller.

Photo: Aviram Valdman/The Tower

He grew up in Tira, located in a region of Israel known as the Triangle that straddles the Green Line separating Israel proper from the Palestinian territories. The vast majority of Israel’s Arabs—who comprise 20 percent of the population and define themselves as Palestinian—live there and in the Galilee.

In 1990, at the age of 15, Kashua was accepted into the Israel Arts and Science Academy (IASA), a Jerusalem boarding school for gifted teens. He quickly realized that his very presence aroused suspicion. “I hated the city as soon as I entered it,” Kashua writes of moving to Jerusalem. “On my first bus ride, a soldier got on and immediately pegged me as an Arab: a boy leaving his village for the first time, with an Arab’s clothes, an Arab’s thin moustache, and most tellingly, the frightened look of an Arab. That was the first time I was taken off the bus and searched. It took me a while to blur my external identity.”

This plunge into the heart of Jewish-Israeli society created the existential paradox that confounds Kashua to this day. At IASA, he says, he learned how to look and act Israeli. He was immersed in the Hebrew language and all the cultural ramifications that come with it. Since then, he has undeniably become the most prominent Arab writer in Israel, and has done so by writing only in Hebrew.

Kashua, much like Abramowitz before him, inserts himself into everything he writes, but does so in a more subtle fashion. His self-referential humor is sly. Rather than name his protagonists “Sayed,” he opts not to name them at all; but it doesn’t take much analysis to understand that they are depictions of himself.

“I like to deal with the characters that I know best,” Kashua told me in a recent interview. Without even pausing for a beat, he adds, “I’m totally in love with myself.” Sitting in a smoky office at the studio that produces his hit television show Avoda Aravit (“Arab labor”), Kashua is aloof, friendly but guarded, and always a bit detached. He offers a great deal of humor and sarcasm but precious few straight answers. His work, he seems to be saying, should speak for itself. And on many levels it does.

The protagonist of each of Kashua’s three novels is a hapless, anti-heroic Arab-Israeli without a name. His debut, Dancing Arabs, is the most obviously autobiographical. It tells the tale of a Palestinian boy from Tira who gets accepted to a prestigious Jerusalem boarding school and ends up marooned between two disparate identities. Rather than define himself as one or the other, he drifts anonymously into adulthood, carrying the weight of his family’s deflated nationalism and dragged down by the tedium of everyday life.

“[Kashua’s] hero does not have a God. He does not threaten with violence, nor does he ask for pity,” wrote Professor Miriam Shlesinger, who translated works by such acclaimed Hebrew writers as Etgar Keret, A.B. Yehoshua, and Shai Agnon. “His life is a masquerade ball, and though he betrays himself, disguises himself, and pours himself from one character to another, he is always honest. And no reader, foreign or local, can remain indifferent to his truth.”

Photo: Aviram Valdman/The Tower

But truth, like culture, is relative. Yosef Haim Brenner, one of the founders of modern Hebrew literature, once said, “A single particle of truth is more valuable to me than all possible poetry.” If Kashua feels the same way, he would never admit it. He is Arab. He is Muslim. But in his day-to-day existence and, more crucially, in his writing, he is as Jewish as Japheth on the train.

The great Hebrew and Yiddish writers of Jewish history, such as Brenner, Micha Berdichevsky, Sholom Aleichem, and Ahad Ha’am, culled the quintessential Jewish experience of living as an outsider and elevated it to literary greatness. Kashua’s second novel, Let It Be Morning, takes the literary ramifications of this “otherness” and pushes it to new heights.

The anonymous narrator of Let It Be Morning is—like Kashua himself—an Arab journalist working for an Israeli newspaper. But unlike Kashua, who a few years ago moved from the East Jerusalem Arab enclave of Beit Safafa to Jewish West Jerusalem, the protagonist decides to drag his wife and baby daughter back to his childhood home in an Arab-Israeli town near the West Bank.

The novel takes place in the wake of the al-Aqsa intifada in late 2000. Kashua’s main character is spurred to action, he tells the reader, by a two-day series of riots. As a journalist, Let It Be Morning’s protagonist is assigned to attend funerals and interview families in mourning. In the midst of it, something inside him breaks.

“Those two days had changed my life,” Kashua, in his trademark first-person narration, writes. “Suddenly, my life as an outsider, which had had its advantages, began to get in the way. My being an outsider was what had qualified me for my job and my position, and had given me the language in which I was expert enough to work as a journalist. My being an outsider was beginning to put my life in danger.”

So he moves back home, forgetting to consider that, while his childhood village has not changed, he has. As politics bubble and churn outside the village’s borders, the narrator’s decision ends up having permanent ramifications, dooming him never to belong anywhere at all.

Perhaps Kashua’s closest collaborator is Shai Capon, a prominent Israeli director who helms Avoda Aravit. Now in post-production on its fourth season, Avoda Aravit is one of the top five Israeli comedies of all time and an indisputable trailblazer for Arab-Israeli actors.

Photo: Aviram Valdman/The Tower

Except for reality shows, Avoda Aravit is the only show on Israeli TV featuring major Arab characters, and certainly the only one with a large part of its dialogue in Arabic. The Israeli media group Keshet admitted they were taking a major gamble when they green-lighted the show in 2007, and initially, they braced for a backlash. And there was a backlash—from Israel’s Arab media. Kashua was accused of indecency, stereotyping, and even treason. But Israeli Jews, who Keshet feared would be in an uproar, for the most part just tuned in and laughed.

“Sayed wouldn’t accept my saying it, but I think that the series made a great change in Israel society,” Capon tells me. “It’s the first time that you see an Arab as a vulnerable human being on Israeli television. Not as a terrorist and not as a victim. Not as anything else, just a simple human being like all of us.”

Constrained by the boundaries of television, Kashua did give his sitcom’s protagonist a name. He is called Amjad, and he is (once again) a journalist working for a Hebrew newspaper. Like Kashua himself, Amjad is married to an Arab-Israeli social worker; and also like his creator, he sends his children to Hebrew-language schools. Amjad embodies an exaggerated version of Kashua’s own troubled identity. In Israel, a nation plagued by xenophobia and casual racism, Kashua is the quintessential good Arab, the Arab who passes, who does not dare to offend.

But there is no sector of Israeli society that Avoda Aravit doesn’t skewer. From the secular to the Orthodox to his fellow Arabs, Kashua uses his deft comedic skills and piercing dialogue to expose the vast hypocrisy of Israel, with its racist conservatives, apologetic liberals, and the helplessness of everyone in between. He can do so because no matter where he stands, Kashua is on the outside looking in.

“Jewish comedians and writers a hundred years ago, like Sholom Aleichem, they were the outsider, the one living in a foreign environment and just wanting to be accepted,” Capon says. “There is a lot of similarity here. The great Jewish humorists were dealing with the same issues. That’s why it’s so close to everybody. It makes it so you can see it from the other side.”

Kashua and Capon are close friends and drinking buddies, spending many post-production nights unwinding together. Their creative process is so intertwined that they share an office, facing each other at parallel desks so they can pass ideas, insults, and spare cigarettes back and forth.

Photo: Aviram Valdman/The Tower

I asked Capon about the similarities between Amjad’s life and that of Kashua. “You cannot write a character that is so far away from who you are,” Capon says. “So yes, I think Amjad is very close to Sayed. He plays on a certain color of his personality. Of course Sayed is more complicated. His personality has a lot of colors in it. This one, however, is a dominant color, and that’s what we see in the series.”

Kashua’s response to the same question was more direct: “Ask Shai,” he told me. “Shai shares an office with Amjad.”

Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that Kashua’s own existential quandaries are given new life in Amjad. During the third season Amjad goes on Israeli Big Brother and pretends (perhaps too convincingly) to be an Israeli Jew; he pretends to have a liberal, free-thinking sister to prove his feminist sympathies; and, noting that there are no Arab vegetarians, he decides to forgo meat so he can become “civilized.”

The season’s finale, however, takes a more serious turn. An air raid siren sounds in the middle of the night and sends all the occupants of Amjad’s Jerusalem apartment building scrambling to the bomb shelter. The elderly Yoske and Yocheved, Arab-Jewish newlyweds Amal and Meir, Amjad, his wife Bushra, and their children are all trapped together behind a steel door. With no cell-phone reception and no clue as to what horrors may be unfolding outside, the neighbors make their true feelings known.

“We really should have let them have it,” one of the neighbors says to another, while Amjad watches from the other side of the shelter. Amjad, aching from being left out, says to the group, “Besides the fact that there’s a war outside, there’s something about this togetherness, right?” They stare at him in silence. Finally, Natan, who outside the bomb shelter is a good friend of Amjad, snaps, “Say, Amjad, why are you attacking Jerusalem?”

Photo: The Tower

Tension continues to build until a full-on political debate has broken out. Someone finds a bottle of vodka and suggests a diverting game of truth-or-dare. But the Jews in the room keep returning to the issue of loyalty: You live here, but whose side are you really on? Maybe it was the Iranians this time, Amjad says, reminding the group that the Iranians are not, in fact, Arab. “Maybe this time,” he says with a twinge of optimism, “we’re in it together.”

Tension continues to build until a full-on political debate has broken out. Someone finds a bottle of vodka and suggests a diverting game of truth-or-dare. But the Jews in the room keep returning to the issue of loyalty: You live here, but whose side are you really on? Maybe it was the Iranians this time, Amjad says, reminding the group that the Iranians are not, in fact, Arab. “Maybe this time,” he says with a twinge of optimism, “we’re in it together.”

But soon the bottle lands on Amjad, and it is his turn to tell the truth. Yoske asks him where he would choose to live if he had the choice between Israel and any Arab country. The camera frames Amjad head-on, and at last, after three long seasons, he is not trying to be something other than himself. Suddenly, the “safe room” takes on a new meaning. If it meant avoiding a lifetime on society’s fringe, Amjad tells Yoske, then yes, he would choose to have been born elsewhere. Even if “elsewhere” means living under the tyranny of Egypt or Syria.

Kashua hesitates when I ask if he sympathizes with his alter ego. “It would be very difficult,” he says, “because I know another reality. I have freedom of speech.” But if it meant knowing his place in society and fitting into a community, then yes, he says, “Sometimes I do think like Amjad.”

In Let It Be Morning, on the other hand, the nameless anti-hero’s dreams of finding a home come from weakness, not national pride.

I tried to survive. I’d always been a survivor. I knew how to adapt to my surroundings, working and doing what I wanted.… But I decided I’d had enough. Somehow I came to the conclusion that it would be much safer to live in an Arab village. Somehow it seemed to me that if I lived in a place where everyone was like me, things would be easier.

Of course, Kashua knows better than to let such fantasies come to fruition. The narrator’s return to his childhood home is marked by all sorts of failures, some of them small and some spectacular. And the novel’s stunning denouement tells us that, for an Arab in Israel, success in life can only come from using one’s outsider status for good. Kashua “is at his core Israeli, but a secondary type of Israeli, and he knows it,” Olmert says. “All the time, he is forcing his readers to deal with the hypocrisy and this gap between what we think about ourselves and how we actually behave.”

This is the genius of Kashua’s writing. In every book, every column, and every episode, he mocks the world around him, but also makes sure to mock himself. No one can say he isn’t even-handed.

“There is this concept in nationalistic thought that there’s an affinity between the language you speak and the territory you live in,” Olmert explains. “When an Arab writes in Hebrew, he’s confusing those affinities because suddenly he’s showing that you can speak and write in Hebrew without being Zionist.… He’s writing for a Jewish audience, and when we read him it’s very confusing. On the one hand you identify with his experiences and on the other hand it’s a very hard mirror to look into.”

Because he is both a part of and apart from Israeli culture, Olmert believes that Kashua is in the ideal position to offer such a reflection. “He shows Israeli culture as racist, full of prejudice about Arabs, lacking self-criticism,” she says. “So his protagonists are always anti-protagonists, anti-heroes.”

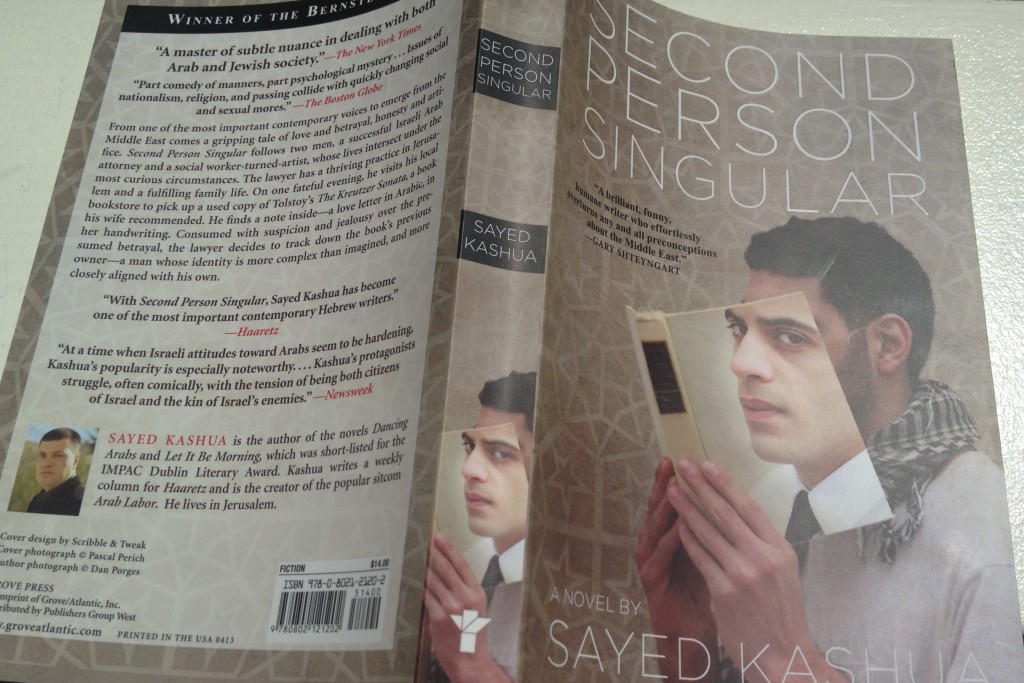

In his third and most recent novel, Second Person Singular, Kashua offers not one but two of these anti-heroes. While one of them, referred to only as “the lawyer,” remains nameless, the second is called Amir. Allowing one of his protagonists the luxury of a first name is not as much of a departure as it may seem, however. Amir is a common first name among both Arabs and Jews, something Kashua makes sure to point out to his readers as the book delves deeper and deeper into identity politics and the lure of “passing.”

It isn’t long before Amir not only sheds his name, but his entire Arab identity. He adopts the personal history of a tragic young Israeli named Yonatan, who is in a persistent vegetative state as a result of a failed suicide attempt. In separate but intertwining narratives, Amir/Yonatan and the nameless lawyer embark on a trouble-ridden quest for acceptance and inclusion in modern-day Jerusalem.

“The plot here is merely the vehicle through which Kashua keenly dissects issues of identity and class,” Scott Martelle wrote in a Los Angeles Times review. And in doing so, Kashua touches the most primal nerve of Israeli life, writing fiction that speaks the truth about race relations and religious tension in this most complicated of countries.

“There is something very sophisticated in his writing,” Olmert says.

It’s all about a very strong passion to become a Jew, to pass. So you know some left-wing Israelis call him by the term aravi machmad (literally, “pet Arab”) like the one who is trying to be cute, to be loved by Ashkenazim, the elite. He is willing to go too far for it, so they accuse him of not really representing the Palestinian cause. He’s always the victim of some criticism. No one really knows how deal with him, and I think that’s part of his charm.

Second Person Singular has been hailed as Kashua’s strongest work yet, the book that will finally cement his place at the pinnacle of Hebrew literature. One review at the popular Israeli website Walla! gushed, “Second Person Singular, Sayed Kashua’s new book, proves once and for all that he is the best Hebrew writer working today.”

What emerges is that Kashua, as an outsider working in Hebrew, has internalized two different Jewish languages: both the modern Hebrew idiom of the new Jew and the millennial, existential struggle of the classical Jew in exile. He knows he is not one of us, yet he is the living embodiment of our own traumatic history. “I’m not trying to tell any truth,” he says. “I’m using materials from my own private experience, if I’m lucky, and I’m trying to deal with a problematic identity and nationality problems. I use humor to take it to different levels.”

“Sayed takes what Israelis think, and he says it out loud,” says Capon. “That’s why Israelis, the Jewish Israelis, accept him.” And he says it in their own language. Kashua pretty much stopped writing in Arabic as soon he enrolled in the Israel Arts and Sciences Academy. While he still speaks it fluently and is perfectly capable of writing Arabic-language dialogue for Avoda Aravit, his grasp of literary Arabic is weak at best. In season three of the program, Kashua mocks his own limitations by showing Amjad, trying for once to write for a Palestinian newspaper, struggle to type a few simple Arabic words on his computer.

“My Hebrew is much better than my Arabic because I haven’t really practiced Arabic since I was 15,” Kashua says. “But I wouldn’t be honest if I didn’t also say that I always wanted to be part of the strong people in Israel. So it was the only way.”

Kashua’s accomplishments are certainly impressive, but the weight of them, Capon says, is also crushing. “In a way, Sayed has the weight of the entire Palestinian nation on his shoulders,” he tells me. “I think the pressure on him is greater than on anyone else. It’s easy to create satire when you’re comfortable in your chair. But it’s harder to do satire when you are in the bloody Middle East, and you are an Arab.”

Olmert explains it differently. Kashua, she says, is not straddling two worlds. He is locked out of two worlds. “Arabs consider him to be too Jewish and Jews consider him to be too Arab. He’s stuck in the middle, exactly like Berdichevsky and Feireberg and Brenner and all those great Jewish writers from the turn of the 20th century that had this notion of not belonging anywhere.”

Even after three successful Hebrew novels, Kashua admits that he still dreams of writing a book in Arabic. It might, he says, bring him that elusive sense of belonging. “Language is just a tool,” he tells me. “Recently, I do think about trying to practice Arabic, reading more Arabic, and maybe one day even writing a novel in Arabic. I have a very strange feeling that my fourth novel will start in Hebrew, and then it will turn into a mix of Hebrew and Arabic, and it will end with Arabic.”

I asked Kashua if such a transition from one language to another would be symbolic. He laughed and changed the subject. The question, he seemed to be telling me, was far too simplistic. Later on, I asked him if he has a message he is trying to deliver to the Israeli people. After all, he has spent his entire adult life working in Hebrew and living among Jews, an Arab Japheth on the chaotic train that is the Jewish state.

“No, no, I don’t have a point,” he says. “I just want everyone to love me.”

![]()

Banner Photo: Aviram Valdman/The Tower

***