One of the biggest barriers to Arab-Israeli reconciliation is the unresolved issue of compensation for Jewish refugees who fled Arab countries in the 1940s and ’50s. A new study explores how the compensation demand arose, then fell into obscurity.

The mass exodus of Jewish refugees from the Arab world remains one of the great untold stories of the 20th century. Indeed, it has been so overshadowed by the flight of Palestinian Arab refugees that even devoted commentators remain ignorant of one momentous chapter in this story: The early attempts by the State of Israel to use the exodus to gain diplomatic leverage over the Arab states. Contrary to popular belief, Israel did not ignore the exodus. It tried to incorporate it into its foreign policy in order to neutralize pressure brought to bear on the issue of the Arab refugees.

For my master’s thesis at the University of Cambridge, I explored the unexamined history of this policy. Delving into Israel’s state archives, I connected the dots between previously unpublished documents and brief references in history books, discovering how Israel addressed the absorption of hundreds of thousands of refugees from belligerent powers. This is the forgotten history of a forgotten exodus.

Israel announced its official foreign policy on the exodus one week after a dramatic decision by Iraq to disenfranchise and expropriate the assets of Jews fleeing the country. In March 1950, Iraq’s Denaturalization Law permitted Jews to emigrate within one year on condition of surrendering their citizenship. Prime Minister Tawfiq al-Suweidi expected no more than 7,000 Jews to leave, but over 100,000 chose to do so. In March 1951, returning Prime Minister Nuri as-Said passed legislation freezing the assets of every denaturalized Jew. Overnight, with Israel unable to keep up with the flood of immigrants, there were 70,000 stateless and penniless Jews stranded in Iraq.

One week later, Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett addressed the Knesset. The government of Iraq, he argued, had “opened an account between it and the government of Israel,” and forced the Jewish state to link this account to one that already existed: The Arab refugees from Israel’s War of Independence. “We shall take into account the value of the Jewish property that has been frozen in Iraq,” declared Sharett, “when calculating the compensation that we have undertaken to pay the Arabs who abandoned property in Israel.”

This principle has been a centerpiece of Israeli policy ever since. Israel effectively nationalized the property of Jewish refugees from the Arab world, claiming an exclusive right to use their private property to write off future compensation payments to the Arabs. Indeed, this point was made explicit in a Foreign Ministry meeting the following week on establishing an agency to register the Iraqi Jews’ claims. “We advise not to announce at least for the meanwhile,” the officials stated, “that personal claims are being registered with the purpose of deducting the value…from the payment of the compensation for the abandoned Arab property.” The Sharett Doctrine was not developed on the fly. In August 1948, Israel had told UN mediator Folke Bernadotte that any peace treaty with the Arab states should pay “due regard to Jewish counterclaims” for “havoc and destruction.” Once the exodus was underway, this demand for counterclaims was merged with the refugee issue: In July 1948, Sharett cabled diplomats that the question of the confiscation of Jewish property would be raised in any peace settlement dealing with the question of Arab refugees.

Ensuring fair compensation for Jewish refugees has been at the center of Israeli negotiation policy since the 1950s.

Fascinatingly, this linkage was not entirely Israel’s idea: Its strongest support came from Baghdad. In 1949, Nuri as-Said proposed an organized Jewish-Arab population exchange to a UN commission, offering a compulsory transfer of 100,000 each way, in which Iraq would confiscate Jewish property as compensation for Palestinian property. This came after Arab states suggested to the UN Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) an “exchange of their [Jewish] population against the Arab Palestinian refugees.” Egypt specifically mentioned a possible “exchange of Jews and Arabs.” Britain rejected Iraq’s proposal, fearing that an expulsion of Iraqi Jewry would provide Jerusalem with “the perfect excuse for refusing to pay compensation for the property of Arab refugees.” It initially preferred a non-compulsory population exchange, although this idea was rejected as impractical. Israel rejected the Iraqi proposal when it was made public in October 1949. Sharett told the Cabinet it would set a “dangerous precedent,” whereby “every Arab country undertakes to accept refugees only to the extent that it has Jews.” But the following month, senior diplomat Ezekiel Gordon said that Israel should take Iraq’s proposal “seriously” and seek an agreement whereby Iraq would take in 300-400,000 Arab refugees in exchange for allowing the Iraqi Jews to emigrate. “This way,” Gordon stated, “there will be no room for the refugees to lodge personal claims against the Israeli government, or Jews against the Iraqi government.”

Gordon’s proposal had much in common with an earlier proposal by World Zionist Organization official Joseph Schechtman. A formal population exchange was desirable, he advised. The only feasible means to achieve it was an interstate treaty in which numerical parity would be irrelevant and the assets of the Jews of the Arab world “could serve as partial compensation for the property left behind by Palestine Arabs.” This idea was by no means farfetched. The relocation of ethnic minorities to their countries of ancestry was widely regarded at the time as “morally acceptable, perhaps even morally desirable … [and] good political sense,” writes Israeli historian Benny Morris. The 1936 Peel Commission partition plan included precisely such an exchange within Mandatory Palestine, and India and Pakistan had just endured a massive population exchange as they declared independence. The Israeli proposal came to naught. Mordechai Ben-Porat, Israel’s chief spy in Baghdad, wired a similar proposal in 1950, but reported that “in Israel, they weren’t enthusiastic.” In any case, the question was soon rendered moot by the mass flight of Iraqi Jewry. With a population exchange now off the table, the question turned to how Israel could secure Jewish property, and avoid being burdened with “tens of thousands of people … naked and destitute,” as Sharett feared.

Population exchanges and compensation for lost property were both proposed, but no equitable and mutually-agreeable solution could be found.

Indeed, Arab governments had already suggested a possible property exchange outside the context of a population exchange. In August 1949, Arab governments proposed to the UNCCP that compensation for Arab refugees be paid in part by an “exchange…between property belonging to Arabs in Jewish territory and the property of Jews in Arab territory.” This came before Jewish property was confiscated. In September, Palestinian refugees in Egypt made the same proposal, according to an Israeli Foreign Ministry fact-finding report. By November 1949, Israel already thought of Jewish property in the Arab world as a resource it could exploit to advance its own policy. The only questions were how and whether to officially make this linkage. One major obstacle was that, at the time, there were many more Arab refugees than anyone thought there would be Jewish refugees. It was not until the mid-1950s that Israel experienced mass migration from North Africa, which pushed the number of Jewish refugees above their Arab counterparts. At the time, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia were part of the French empire, and Israel had its sights on Jewish immigration from elsewhere. One audacious proposal, discovered in an undated and anonymously-authored Foreign Ministry document, suggested that parity ought to be achieved on the basis of population density. Iraqi Jewry was entitled to a “share” of Iraq’s “national patrimony” based on its percentage of the population: Namely, 15,000 square kilometers of land, compared to 5,200 square kilometers for the Arabs who left the smaller Israel. Alternatively, Jews were “entitled to 80,000 square kilometers [four times the size of Israel] on an Arab reading of a fair post-World War settlement” as a “successor element” of the Ottoman empire. If anyone was “entitled to be compensated for losing on the bargain,” said the document, it was Israel. In fact, there would be “nothing illogical or farfetched” in a claim to Iraqi public property, which might be “raised even as a bargaining point or for mere emphasis.”

Jewish immigrants from Iraq arriving in Lod Airport, 1951. Photo: National Photo Archive / Wikimedia

These were not the only forms of linkage envisioned by Israeli policymakers. One abortive plan came from Foreign Ministry official Ezra Danin, who was asked by officials acting on the prime minister’s behalf to “inquire as to the possibility of exchanging property of non-absentee Israeli Arabs for property of Jews in Iraq.” The collapse of asset prices in Iraq as Jews hurriedly liquidated their property rendered this option viable, given the desire of wealthy Iraqis to stabilize prices. Danin sent Finance Minister Eliezer Kaplan an intriguing proposal in June 1950: He had found “a number of Arabs” who wanted to leave Israel and were prepared to exchange their property. Israel would compensate Iraqi Jews from these funds, and Iraq would do the same for Palestinian Arabs. Time was not on Israel’s side, warned Danin, but it might still be possible “to save most of the Jewish property … bound to wind up in the [Iraqi] treasury.” Danin was building on ideas already in circulation: The day after the Iraqi Denaturalization Law was enacted, the Mossad urged Jerusalem to formulate a policy on exchanging Jewish for Arab refugee property before the depreciation resulting from a mass liquidation rendered it irrelevant to “Israel’s debt to Arab refugees.” It further suggested that Palestinians in Iraq “may be interested in exchanging property in Israel for Jewish property in Iraq.”

Crucially, when the mass exodus of Iraqi Jewry began, Israel still had no coherent policy on Jews from Arab lands.

The day after Kaplan received this sensitive proposal, the prime minister’s land affairs advisor intimated that Danin had “made the requisite contacts…with authorities in Iraq.” It remains a mystery how he did so and at what level. He urged the government to establish a “special company under government supervision” to handle the exchange. In July, Kaplan allocated a small budget “to commence the exchange of property,” charging a small commission for the service. Nothing came of the plan. Danin blamed delays and financial constraints, and it was soon rendered irrelevant by the mass exodus of Jews from the Arab states. Crucially, therefore, when the mass exodus of Iraqi Jewry began, Israel still had no coherent policy on Jews from Arab lands. In a November 1949 memo, Gordon stressed that he was still unsure “whether it is [even] to our advantage to link the two questions” of Arab refugees and Jews who were mostly not yet refugees. Policy was so muddled that Jewish capital was being smuggled to third countries. Ben-Porat blamed the Treasury’s “abysmal lack of foresight” for demanding a 20 percent commission for importing capital. By the time a policy was formulated, the idea of using Jewish assets to write off the debt to Arab refugees was little more than an attempt to make the best of earlier, failed attempts to exchange actual property. And when Sharett announced his doctrine in the Knesset in late March 1951, the nationalization of Jewish property in the Arab states was a done deal. Sharett’s doctrine evolved over the years, but fundamental deliberations on strategy died on that podium.

If this was Israel’s policy, what became of it? The historical records are sketchy, but it is possible to decipher the story of a policy that everyone understood was important but failed to get off the ground.

In 1949, the UNCCP convened the Lausanne Conference to follow up on the armistice agreements that ended Israel’s War of Independence. This was before the Sharett Doctrine was formulated, and Jews fleeing Arab lands already had claims to make. The American Jewish Committee sent Israeli negotiators a briefing on these losses to rebuff Arab refugee claims. The idea went nowhere, and the Lausanne talks did not produce an agreement in any case. In addition, the UNCCP had already rejected Israel’s original demand to link claims for war damages to the Arab refugee question. Israel tried to enlist the diaspora as a diplomatic backchannel to rescue Jewish property. In May 1950, a Board of Deputies meeting in London was addressed by Member of Knesset Eliyahu Eliashar, who proposed that Iraq entrust Jewish property “to a custodian…which would organize the transfer” of assets to Israel. Although Eliashar claimed to be speaking in a private capacity, it is clear from a Foreign Ministry memo that he had been sent specifically to “enlist British Jewry” to advocate such a policy to the British government, since the Israeli mission could not openly participate in such lobbying “for obvious reasons.” The British Foreign Office not only refused the Board of Deputies’ appeal, it even reserved the right to deport Iraqi Jewish émigrés from Britain. Similar appeals by American Jewry were also to no avail.

Once the Sharett Doctrine was announced, Israel publicized it internationally. On March 20, 1951, the Foreign Ministry forwarded to British and American ambassadors a copy of a secret diplomatic message sent to ministers. Israel warned the U.S. that “widespread violence” was likely unless the U.S. could prove a “moderating influence” on Iraq to facilitate an orderly evacuation of Jews with their assets. For international consumption, Israel warned that “if Jewish property can be despoiled without challenge, this form of plunder is likely to be extended…to foreign interests.” Foreign Ministry Director Walter Eytan also wrote to UNCCP chairman Ely Palmer, with a twist. Whereas Israel had previously offered to contribute to the Arab refugees’ Reintegration Fund, “it will be evident that [it] cannot fully discharge [this] obligation,” Eytan warned, “if, in addition to all the other burdens it has assumed in regard to the absorption of new immigrants, it now finds itself compelled to provide for the maintenance and rehabilitation of over 100,000 Jews.” Israel’s inability to do anything for the Arab refugees was compounded by Iraq’s confiscation of Jewish wealth, which “could have been of great help” in meeting this commitment. If Baghdad allowed the Jews to leave with their assets, the need for linkage would disappear. Israel forwarded copies of the statement to all its embassies.

Efforts to resolve the refugee crises using Diaspora Jews as backchannel diplomats utterly failed.

But Israel proved unable to use this doctrine to deflect diplomatic pressure. The UNCCP refused to endorse it. When it forwarded copies of the letter to Arab governments, they never replied. Israel eventually unblocked Arab bank accounts at the UNCCP’s request after Israeli UN Ambassador Abba Eban’s plea that “equal concern” be given to Jewish refugees fell on deaf ears. According to historian Michael Fischbach, Israel conceded because it had only registered one tenth of frozen Jewish funds, and thus had no cards to play. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the Jewish exodus from Arab lands slipped into obscurity. When Israel proposed its Blueprint for Peace at the General Assembly in 1952, the exodus featured at most indirectly: Eban cited the “vast influx of population into Israel from…the Arab world” as one reason why the clock could not be turned back to the 1947 partition plan, as the Arabs belatedly demanded. Eban did not mention the Jewish refugees in his comments on Arab refugees. Little wonder that Israeli diplomats were soon confused about their country’s official line on the matter. In June 1955, diplomat Gershon Avner at the London embassy demanded “clear instructions” from the Foreign Ministry on “whether we are still speaking about” taking confiscated property into account or “whether this point has fallen off the agenda.” He noted that the point had previously been “important,” but noticed that politicians had started discussing Arab refugees without reference to counterclaims. Avner received an immediate, fiery reply. “The question of compensation has not fallen off the agenda,” retorted senior official Gideon Rafael; moreover, policymakers were reconsidering “the possibility of individual compensation payments to property owners.” Israel had “never given up” on registering the Iraqi Jews’ claims, Rafael clarified, and would announce a new registration committee soon.

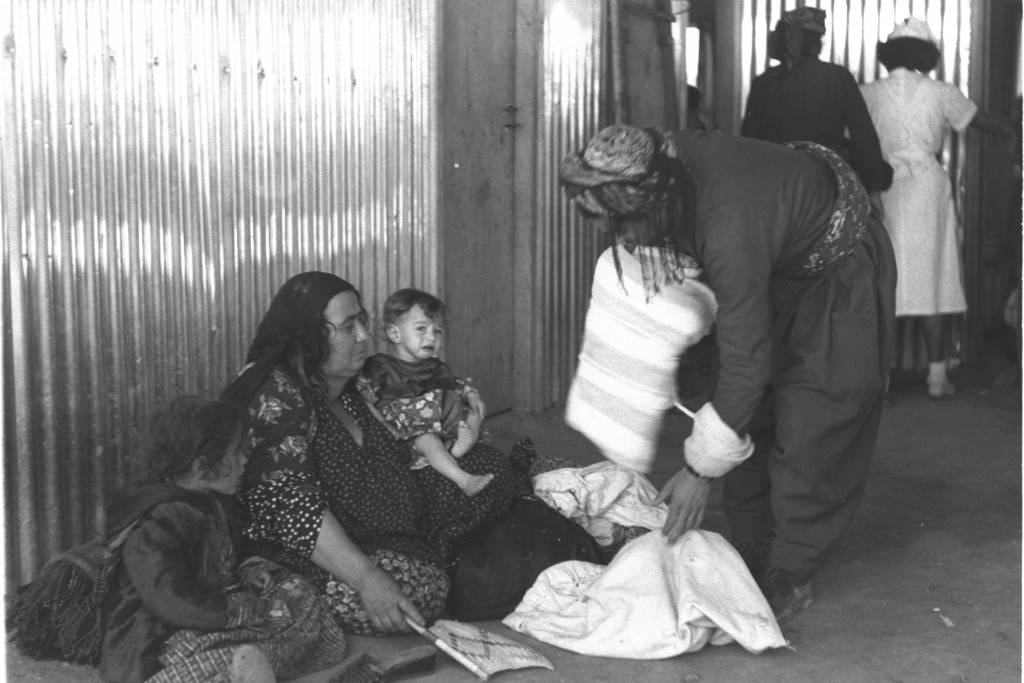

Jewish refugees at the Beit Lid refugee camp, 1950. Photo: Seymour Katcoff / National Photo Collection / Wikimedia

Previous drives had produced “virtually nothing,” since skeptical immigrants were not interested in cooperating. Indeed, an earlier report – which had recommended the policy be dropped because of a lack of data – was gathering dust. But Rafael stressed that Israel was still raising the issue at international fora, including at the UNCCP the previous year. Shortly afterwards, Eban invoked the exodus at the UN’s Special Political Committee in November 1955. He argued that “the capacity of the Arab world to absorb this [Arab] refugee population has been increased by the emigration to Israel of 350,000 Jews.” He made the same point in the same forum in 1958, but again made no reference to the compensation policy. The question of compensation returned to the agenda in 1956, when Egypt expelled its Jews amid the Suez War. Foreign Minister Golda Meir used the persecution of Egyptian Jewry to hammer Cairo at the General Assembly, but did not seriously pursue justice for the expellees: The matter did not appear in her November letter to the Secretary General with a list of questions for Egypt during the crisis. Instead, diaspora organizations lobbied for the rights of Jewish expellees from Egypt, with Israel’s knowledge and blessing. The Joint Distribution Committee, together with the semi-governmental Jewish Agency, appealed without success for Egypt to put the confiscated Jewish assets at the disposal of the Red Cross.

The quest to resolve the issue of compensation for Egyptian Jews was just as unsuccessful as the drive to do so for Iraqis.

Israel was keen for Egyptian Jews to depart with their assets, because the cost of absorbing yet more penniless refugees was placing an enormous strain on national finances. The Jews had been allowed to leave Egypt with travelers’ checks of £100 and those who reached Israel could only withdraw £20 because Britain refused to allow the checks to be cashed outside of the sterling zones or by non-nationals. The Foreign Ministry was forced to intervene when the Bank of England refused the Israeli Bank Leumi’s request to allow the withdrawal of £40,000 of accumulated checks. What followed illustrates the sheer obstinacy of the great powers’ refusal to assist Israel with its refugee burden. The UK Treasury informed the Israeli embassy that Britain was “unable” to revise its decision, since it had never made an exception for non-Jews “of several nationalities residing outside the sterling area.” The embassy retorted that most non-British refugees were in Israel, so this point was “more academic…than practical”: Would the UK reconsider in light of the “humanitarian” dimension? The Treasury replied that it would not release cash outside of a “general settlement,” and unhelpfully replied that Egypt might meet the uncashed balance from its own sterling account “if her own authorities can be persuaded.” Britain, the official said with characteristic passive-aggressiveness, would not object. At its wits’ end, the Israeli Foreign Ministry persuaded the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to intercede. The British Foreign Secretary did not respond favorably. Britain and France later reached separate agreements with Egypt for compensation for their own nationals, also expelled during the Suez crisis, leaving the nationless Jews by the wayside. When Israel signed its own peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, the treaty only made provisions for a claims commission. It has yet to be convened.

It is common to say that Jewish refugees from Arab lands have been “forgotten,” as if the political significance of a massive influx of refugees from enemy states never dawned on Israel. But once one delves into the history, one discovers that the issue was very much on the minds of Israeli policymakers. Israel understood that it had a card with which to try to neutralize a major threat—the demands of the Arab refugees, which were artificially kept on a low flame by Arab governments opposed to their resettlement.

But this card was never successfully played: Israel found that neither the regional political situation nor international opinion were sympathetic to its arguments. What was forgotten was not the diplomatic potential of the refugee issue itself, but the fact that Israel was aware of that potential, and frustrated at every attempt to make use of it. In Israel, there is now much discussion of the idea of a regional peace settlement with the Arab world. It is an open question whether the issue of the Jewish exodus from Arab lands will be part of this discussion. If so, it would not be the first time that Israel contemplated leveraging this issue on the international agenda. Contrary to popular myth, Israel has indeed tried to get justice for its own refugees, and may well do so again. ![]()

Banner Photo: Jewish Agency for Israel