In 1991, The United Nations repealed the infamous resolution equating Zionism with racism. Yet unbeknownst to most of us, a whole network of anti-Israel institutions and funding streams created at the time remained firmly in place, and continue fueling anti-Israel sentiment around the world.

The April reconciliation agreement between the Palestinian Authority’s dominant Fatah faction and the Islamist Hamas movement has come as a shock to many. It shouldn’t have. In the weeks before the deal, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas had already taken steps with a profoundly negative impact on the U.S.-sponsored peace talks. Building on his modest success in winning a 2012 UN General Assembly vote to upgrade the Palestinian Authority’s status to that of a non-member state—a designation it shares only with the Vatican—Abbas returned to this unilateralist strategy of peace avoidance by signing 15 applications for membership in a variety of international agencies, conventions, and treaties.

Abbas’ goal is obvious: By embedding a virtual “State of Palestine” into the complex infrastructure of the United Nations, he hopes to massively increase international diplomatic and legal pressure on Israel, render the Jewish state vulnerable to international sanction as a rapacious colonialist occupying power, and achieve “statehood” without any compromise required by peace negotiations. This latest attempt at “diplomatic warfare” pursues many of the same aims as did decades of failed conventional wars and terrorism, yet it enables the Palestinians to do so without explicitly resorting to violence, addressing the demand to recognize Israel as a Jewish state, or any other necessary accommodation. Abbas knows he has a great deal of support for such a move. He can count on the votes of Arab and Muslim states in the General Assembly, as well as their allies in the developing world, to make Palestinian statehood a reality—at least on paper.

That the UN would endorse this approach, which sets out to undermine the peace process and render it irrelevant, while violating previous agreements with Israel, should not be surprising. The UN’s systemic antipathy toward the Jewish state is well-documented.

Indeed, even UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon has conceded that “Israel has been weighed down by criticism and suffered from bias—sometimes even discrimination” in the international body.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas during a joint press conference at Abbas’ headquarters in Ramallah, August 15, 2013. Photo: Issam Rimawi / Flash90

The most glaring example of this tendency was UN General Assembly Resolution 3379, which horrendously declared Zionism to be a form of racism. Passed in 1975 following a sustained campaign by the Soviet Union, and rescinded in 1991 after a major push by the United States, the resolution triggered a measure of international revulsion, as it symbolized the extremity of the UN’s aversion to one of its own member states. But what few people realize is the extent to which we are still living with the resolution’s influence—especially in the form of a network of extremely well-funded UN structures and offices that have until now remained largely hidden from public scrutiny.

Despite the “Zionism-is-racism” resolution having been annulled, these offices, agencies, and committees continue operating as the engine of the effort to delegitimize the Jewish state and attack it through boycotts, sanctions and divestment. It is these structures and their activities that are being exposed here systematically for the first time.

Resolution 3379, passed on November 10, 1975, remains one of the darkest chapters in UN history. The text “severely condemned Zionism as a threat to world peace and security,” spoke of Israel and apartheid South Africa as “organically linked,” and declared that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.” By contrast, its repeal in Resolution 46/86 was the shortest resolution ever approved by the General Assembly. Passed on December 16, 1991, it consisted of a single line: “The General Assembly decides to revoke the determination contained in its resolution 3379 of 10 November 1975.” Despite this telling brevity, one might reasonably conclude that the UN had finally corrected one of its most shameful errors.

Except that, as is often the case with the UN, nothing is ever as simple as it seems. The claim that Zionism is a form of racism was not confined to a single resolution. It was and still is essential to the position that many UN agencies take on the existence of Israel, the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict, and its subset question of Palestinian statehood. This attitude is predicated on the ahistorical assertion that Israel is a state dominated by non-indigenous colonizers, and thus Israel’s primary mission is to frustrate any and all attempts at self-determination on the part of the “indigenous” Palestinians. That this attitude is still embraced is painfully visible through the activities of the UN’s “Division for Palestinian Rights” and its related committees—an infrastructure created by another resolution the same day the UN declared Israel’s very existence to be “racism.” Most importantly, it is a view that continues to inform and guide Palestinian unilateralism and the accompanying efforts to delegitimize Israel at the UN. As Abbas has again demonstrated, the legacy of Resolution 3379 is alive and well.

The goal of the 1975 Zionism-is-racism resolution was to depict Israel as a racist state, an illegitimate Middle Eastern version of colonialism in Africa, much like the apartheid regime in South Africa at the time. This goal was furthered by a 1981 General Assembly resolution known as “uniting for peace,” which called for the recognition of Namibia, then occupied by South Africa, as an independent state. At the same time, it described the apartheid regime as a “threat to international peace and security” and sought to subject it to a UN-coordinated boycott campaign.

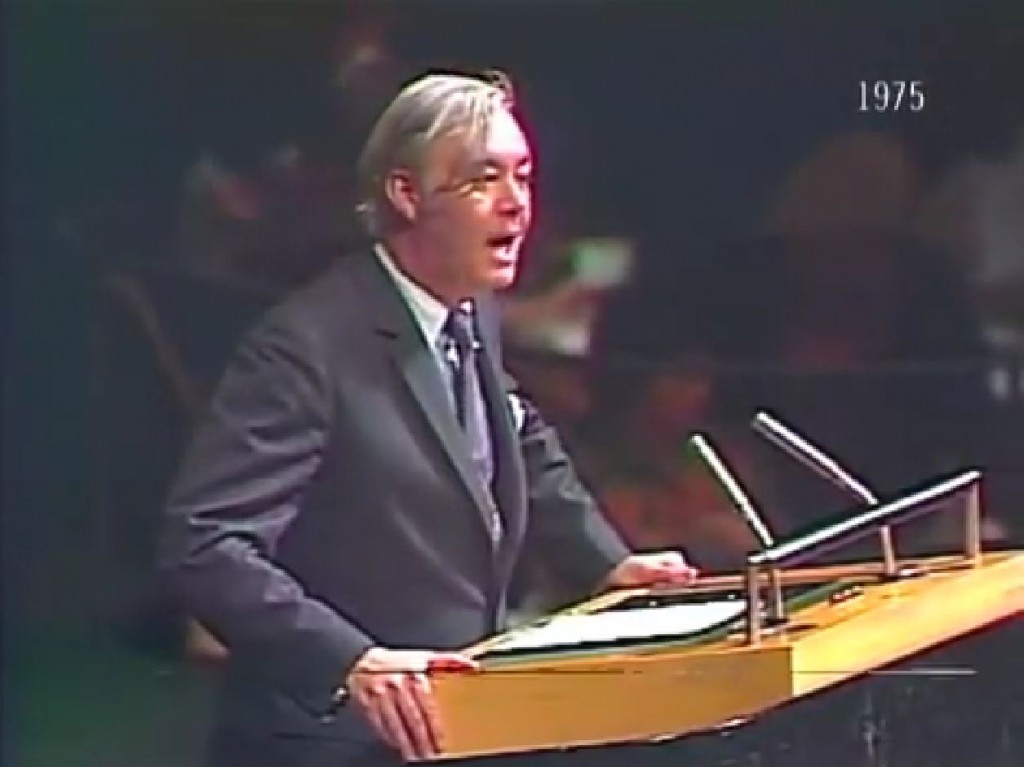

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, United States Ambassador to the United Nations, spoke in opposition to UN Resolution 3379 in 1975. Photo: Legal Insurrection / YouTube

Credit for identifying the Namibia precedent as a diplomatic warfare tactic directed at Israel resides with the American Jewish International Relations Institute (AJIRI), a policy organization that diligently tracks what it has identified as “the UN propaganda apparatus whose purpose it is to delegitimize the State of Israel.” AJIRI’s founder, Ambassador Richard Schifter—a storied diplomat who served as an American ambassador to the UN during the 1980s—explains that, in the early 1970s, Fidel Castro and Muammar Qaddafi began a campaign to take control of the General Assembly’s agenda. “Their goal was to use the General Assembly to embarrass the United States and delegitimize Israel,” Schifter explained. “The idea of drawing a parallel between Israel and South Africa emerged at that time, as former colonies became UN member states. It is in that context that the Zionism-is-racism equation came into being: To attract the votes of sub-Saharan African member states to the Castro-Qaddafi coalition.”

In propaganda terms, AJIRI’s Special Adviser Gil Kapen told me, the analogy to apartheid South Africa “carries an in-built legitimacy in UN forums. The Palestinians know that successfully presenting themselves as the victims of an apartheid system carries automatic advantages.” This reflects apartheid South Africa’s standing as the UN’s first pariah state. That status was no doubt deserved. Nonetheless, there a substantial amount of hypocrisy involved. Such a designation could easily have been applied to the myriad tyrannies and autocracies that still form a sizable voting bloc at the UN, for example. Moreover, it was an early example of the penchant among member states, many themselves pariahs or adversaries of the West, for selectively ignoring the core UN principle of sovereign equality. Indeed, the same states that rushed to accurately condemn South Africa and then defame Israel as bastions of racist repression routinely invoked the sovereignty principle in order to deflect scrutiny of human rights abuses within their own borders, and in the Soviet Union and its allies.

“You cannot create an environment of trust because Israel has been treated as a pariah for so many years. How can Israel trust the UN? How can many Palestinians, when the UN has failed to deliver a solution?”

More importantly, however, the 1981 Namibia resolution provided a template for future attacks on Israel, which have too often echoed its determinations almost note for note. The first half of the text was a litany of South African offenses in Namibia, together with fulsome statements of support for Namibian independence and the recognition of SWAPO, the guerilla movement which fought the South Africans, as the “sole and authentic representative of the Namibian people.” This format is regularly followed with regard to Israel and the PLO. At the same time, the latter half of the resolution dealt with punitive measures against South Africa, the overall goal of which was to urge member states to cease “all dealings with South Africa in order totally to isolate it politically, economically, militarily, and culturally.” Again, these are the measures that the Palestinians and their supporters often seek to apply to Israel.

Thus, the enemies of Israel established a model that institutionalized the hypocritical abuse of the sovereignty principle by elevating the practice of selectively isolating member states because of their internal systems of government—“Zionism” in the case of Israel (because it is “racism,” you see). As a result, Israel became the target of an entire UN bureaucracy that produced endless resolutions condemning Israel at the UN General Assembly and the Commission for Human Rights, now known as the Human Rights Council. Indeed, decades after the passage of the Zionism-is-racism resolution, between 2006 and 2013, Israel was the subject of 45 resolutions condemning it—almost as many as the whole rest of the world. It is the only country with a permanent agenda item of the UNHRC, and was the subject of no fewer than five condemnations in the winter 2014 session alone, while only one resolution addressed the horrific use of chemical weapons and barrel bombs in Syria. (As if to even balance this out, one of the five resolutions against Israel concerned its treatment of Syrian citizens on the Golan Heights.) Underneath all of this public-facing hate speech posing as concern for human rights, however, is a more secret bureaucracy aimed at undermining Israel’s legitimacy around the world. At the heart of what AJIRI calls the Palestinian “propaganda apparatus” is the Division for Palestinian Rights (DPR), a component part of the Department of Political Affairs. With an annual budget of around $6 million, two committees operate within the DPR, cumbersomely named the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Human Rights Practices Affecting the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories and the better known Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People (hereafter referred to as the “Palestine Committee”).

Among NGO advocates who work on the Palestinian issue, the Palestine Committee is the source of greatly appreciated support, financial largesse, and international networking through the annual seminars it organizes in different parts of the world, which bring together the most prominent and hostile anti-Zionist activists from around the globe, including a smattering of Israeli Leftists and anti-Zionists. These conferences take place annually in every corner of the globe, and provide the inspiration, glue, and international backing of the United Nations for the activists and organizations who seek to accomplish what decades of war and terrorism failed to achieve–what Iran called “A World Without Zionism.”

In April 2013, for example, a conference for Latin America and the Caribbean was held in Venezuela. The seminar merrily recycled the standard positions of the Palestine Committee, such as support for the so-called Palestinian “right of return” and effusive endorsement of Palestinian unilateralism. As AJIRI concluded in its report on the seminar, the objective “was to present to Latin American and Caribbean states in the form of a UN Declaration the Palestinian arguments for the delegitimization of Israel. It was most certainly not intended to advance the cause of peace.” Ironically, it took place just days after the victory of Nicolas Maduro—handpicked successor to Hugo Chavez—in a presidential election marred by voter fraud and violent intimidation of the opposition. Those real-world abuses outside the conference hall didn’t merit the attention of the delegates.

AJIRI is not alone in citing the UN’s Palestine Committee as an obstacle to securing an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement as well as a body that is easily exploited by authoritarian governments. Diego Arria, a former Venezuelan Ambassador to the UN and special adviser to the secretary-general, told me that the Committee allows “governments like the one in Venezuela to use the Palestinian cause to bash the Israelis and fundamentally the Americans.” He also stressed that there is a long tradition of using UN conferences and seminars solely to pummel Israel, without offering any positive or practical advice to the Palestinians.

In 1976, for example, Arria was head of the Venezuelan delegation to the UN Conference on Human Settlement, held in Vancouver. He was asked by an Iraqi delegate to visit his hotel suite for a consultation. “I arrived on my own, and there were maybe ten Arab representatives waiting,” Arria recalled. “They addressed me as their ‘OPEC brother’ and said, ‘We need you. We are planning to expel Israel from the conference.’ I asked them why. They cited the ‘Zionism is racism’ resolution.” When Arria dissented, the Iraqis threatened to call his superiors in Caracas. “At that moment, I got up and left, slamming the door on my way out,” he said, smiling.

The bigotry that plagued Israel in 1976, Arria reflected, remains firmly in evidence today, and effectively prevents the UN from being an honest broker in the conflict. “You cannot create an environment of trust because Israel has been treated as a pariah for so many years,” he said. “How can Israel trust the UN? How can many Palestinians, when the UN has failed to deliver a solution?”

The counter-argument to this view, and it is certainly a familiar one, is that the UN’s Palestine infrastructure is of microscopic relevance when compared to Israel’s military might and international political clout. Do away with the occupation, it is claimed, and there will be no need for any more committees with unwieldy names devoted to the Palestinian cause.

There is a serious problem with this argument: The demonization of Israel and Zionism that created this infrastructure predated the occupation by about 18 months. On October 15, 1965, the New York Herald Tribune carried the front page headline “Soviet at UN Lumps Nazism and Zionism,” reporting on the stormy clashes accompanying the UN’s attempt to draw up its Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The Soviet representative insisted that the committee had to condemn Zionism alongside Nazism and anti-Semitism.

There were two reasons behind the Soviet position: First, cozying up to its Arab allies; second, deflecting international attention away from the persecution of Soviet Jews, which a condemnation of anti-Semitism might encourage. Sure enough, a typical UN compromise was reached, according to which the only form of discrimination condemned was “apartheid.” In other words, 20 years after the Holocaust, the Soviets and their anti-Western allies had ensured that the UN was banned from condemning anti-Semitism by name.

But it didn’t end there. As Israeli scholar Yohanan Manor wrote in To Right a Wrong, his fascinating book on the Zionism-is-racism resolution, the convention “showed the Arabs and the Soviet Union that it was possible to have Zionism condemned if they could just find a way to secure the support of the Afro-Asian bloc.” Ten years later, they achieved just that with the passage of Resolution 3379.

Israeli ambassador to the United Nations Chaim Herzog rips up Resolution 3379 while denouncing it from the plenum in 1975. Photo: Hebrew University of Jerusalem / YouTube

The notion of Zionism as racism, then, permeated the UN long before Resolution 3379, thanks to the unrelenting propaganda of the Soviet Union and its communist and Arab allies. “The USSR masterminded the resolution on Zionism. It was a dimension of their strategy to bring about the expulsion of Israel from the UN,” Manor told me. In this sense, it is fair to say that the Soviet demonization campaign failed. Far from being expelled, Israel’s standing at the UN has been quietly enhanced, especially in recent years. This has been demonstrated by Israel’s admission to the Western European and Others regional grouping (WEOG) after years of isolation through Arab refusal to admit Israel to the Asian regional group.

But there is also a legacy of success; one that has outlasted even its Soviet enablers. The persistence of the UN’s Palestine infrastructure, born from the same votes on the same day that gave us the Zionism-is-racism resolution, suggests that the 1991 repeal of Resolution 3379 in that rather sullen single line was, at best, an act of bad faith. For whatever the official record says, there remains a UN division devoted to nothing but political and diplomatic warfare against Israel.

I asked Ambassador Schifter why the 1991 American campaign to repeal Resolution 3379, intended as a gesture of encouragement to Israel as it prepared to meet its Arab foes in Madrid, did not include the dismantling of the Palestine infrastructure.

“Nobody pays attention to the details, that’s the real problem,” he replied. “The votes would have been there to end the Committee and the Division of Palestinian Rights, but it was overlooked. The State Department is really concerned with bilateral relations, and while the U.S. worked hard to get the votes to repeal the declaratory ‘Zionism is Racism’ resolution, the parallel operational aspects were not addressed.”

Each November 29, and it is not a coincidence that this is the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, the mandates and funding for the anti-Israel diplomatic warfare machine of the DPR and its fellow committees come up for renewal. The votes in favor are pretty much automatic, says Schifter, but could be turned under different circumstances:

A significant number of ambassadors in New York vote against Israel without instructions from their governments. Because these resolutions involve budgetary questions, they require a two-thirds majority vote under the provisions of the UN Charter. So the answer to the problem is that you reach out to heads of government. You get them to give instructions to the ambassadors on how to vote.

One milestone in securing the dismantling of the DPR, Schifter believes, would be for the Europeans to vote against renewal of the mandates instead of abstaining. “Germany would be the one to lead it,” he said. “But I don’t know if anybody’s asked them.”

Such a change, Schifter argues, would be good for the UN itself. When he served at the American UN mission, he told me, he and his colleagues would “distinguish between ‘UN World’ and the real world on the other side of First Avenue.” By dismantling the UN’s anti-Zionism Palestine infrastructure—or even, as Diego Arria suggests, converting it into a body concerned with Palestinian economic development—the UN would dissolve one important barrier between itself and the real world.

But more than anything else, such a change in the UN infrastructure would advance the cause of peace. At the moment, the UN’s institutional treatment of Israel and the Arab-Israeli conflict encourages Palestinian hatred, legitimizes their rejection of Israel’s right to exist, increases Israeli mistrust, alienates its supporters, and, above all, enables the type of Palestinian unilateralism that undermines the peace process and prolongs the conflict. A renewed effort at reform by influential member states would go a long way toward changing this state of affairs for the better.

Such an effort would end the UN’s hypocrisy on the issue and help it live up to its founding principles. The institution’s selective violation of its own sovereignty principle, its double standards toward the Middle East’s only democracy, its obvious political bias, and its unrelenting assault on the legitimacy of Jewish self-determination would end.

But as long as the UN’s “propaganda apparatus” for Palestinian rejectionism survives, the world body’s essentially positive nature will be disfigured by well-founded accusations of discrimination against its only Jewish member. For the good of Israel, the Palestinians, and the UN itself, it is long past time for the world body to finally say farewell to the libel that Zionism is racism.

![]()

Banner Photo: michaklootwijk / 123RF