The Jewish people have a debt they can never fully repay to those who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. But the Jewish state has gone some way to provide for them in their old age.

In a Jerusalem apartment, an elderly woman misses a roommate like no other. Together, the two of them cheated fate and formed a bond that would make a Jewish woman and a priest’s wife inseparable.

Galina Imshenik once used her status as a respectable Christian to shelter a young Jewish child, Elena Dolgov, during the Holocaust. Decades later, they ended up together in Jerusalem.

A set of three pictures on the wall of their apartment tells two life stories and one shared fate. There is a picture of the village in Belarus where Galina and her husband protected Elena throughout the Holocaust. There is a picture of St. Petersburg, where Elena lived afterwards. And there is a picture of Jerusalem, which the two women made their home in 1992.

During the war, Galina and her husband looked after Elena’s every need and even taught her to treat them as parents. Elena’s habit of speaking Yiddish was dangerous if other people were around, and the couple’s determination to teach her Russian saved her life when the Gestapo questioned them and left with the impression that Galina and her husband were Elena’s biological parents. Six decades later, Elena looked after Galina’s every need, nursing her through a long illness until her death in 2011.

They shared the apartment in Jerusalem for almost 19 years. “It was a connection like a connection between mother and daughter,” Elena says, recalling the holidays they celebrated together—both Jewish and Christian. “Our festivals were her festivals and her festivals became our festivals.”

People with stories like Galina’s, individuals who found themselves drawn to Israel after rescuing Jews during the Holocaust, live dotted around Israel, rarely telling their stories to the media. All of them were born non-Jews and therefore free from persecution by the Nazis. But they put their lives at risk by helping Jews and later immigrated to the Jewish state. Galina did so with the woman she saved, but many others did so alone, and since the 1980s they have been guaranteed automatic residency based on their status as “righteous among the nations.”

Around 130 people have come to Israel via this unusual route, and the state treats them with reverence. The poverty of Holocaust survivors is a source of constant controversy, but those classed as righteous among the nations receive the country’s average salary as a monthly stipend from the government.

Today, only 13 are still alive.

In the northern Israel community of Kiryat Tivon, one wonders what Robert Boissevain would have thought if he saw his daughter living here.

His decision to hide Jews for two-and-a-half years during the Holocaust cost his children dearly. They didn’t just go hungry, watching their food shared with the fugitives, but they were also told not to play with or even talk to other children, lest their secret slip out.

But none of this bothered Robert’s daughter Hester, who decided in her adulthood that she wanted to help the Jewish people once again.

In the early 1960s, the 27-year-old Hester, a newly-qualified nurse, bought a one-way ticket and boarded a ship to Israel. “I thought that I can go somewhere with my profession, and remembered that in 1948 lots of refugees were going to Israel and I recalled pictures of thousands of immigrants arriving in Haifa,” she says.

As she speaks all these years later, she understates the unusual nature of her decision: “I said that if I would maybe go and help people with my profession where they need nurses, like Africa, why wouldn’t I go to Israel where they also need people? So I went to the Israeli embassy in Holland and said I want to go to Israel.”

Looking back on it now, she says it wasn’t only about wanting to help, but also about finding a place where she felt comfortable. Hester lost a great deal in the war. Her home was destroyed and her family’s wealth confiscated. Her father Robert was a fearless resistance fighter who ended up in prison and then in the concentration camps. He collapsed and died moments before liberation.

As well as feeling weighed down by history, Hester felt that post-war Holland wasn’t the same country. “Holland changed after the war,” she says. “It was destroyed and the country had to have a new life. But it was too organized and I said that I didn’t feel at home with all this organization, so I’ll go to Israel.”

In the young Jewish state, she certainly found an antidote to over-organization. Arriving on a kibbutz to take up her first position as community nurse, she found chaos in the clinic, “even discovering medicines and bullets in the same jars.” Within days she had the place ship-shape, and was working far more than the required hour a day, offering counselling to “troubled” young people. She was soon cycling to two other locales to provide medical care and working in a hospital. She toiled 16 hours a day at four jobs until she moved to Kiryat Tivon and took a community nurse position in the mid-‘60s.

When she retired after decades in nursing, she made another contribution to Israel, opening a cafe near her home that was operated entirely by people with disabilities. It made people rethink their relationship to disabled people, and gave its staff new skills and confidence. She helped to run the establishment until it closed two years ago.

The plethora of stories in Hester’s family defies belief. There was the aunt who saved dozens of Jewish babies by carrying them away from the Nazis one-by-one in a backpack, and the banker uncle who managed to siphon off Nazi funds and pass them to Jews in hiding. And, of course, the story of her own parents and siblings.

Their role as rescuers began one afternoon in March 1943, when Hester’s father phoned her mother Helena asking her to prepare dinner for guests at the Haarlem house where the family lived. That night, the Goldbergs arrived. They were an elderly couple and a daughter aged almost 30 from Russia who had come to Holland through Finland and Germany looking for safety. “They came for dinner and stayed for two-and-a-half years,” recalls Hester, adding that for some of the time the family also sheltered a Jewish dentist.

Their neighbors were Nazi collaborators, heightening the need for effective subterfuge. Hester’s father was fighting with the resistance, and her mother had to scrounge for food, devise plans for when soldiers called, run regular surprise drills, and preserve peace in the tense household. She sometimes served tulip bulbs instead of potatoes, and often cycled up to 75 miles—usually on metal wheels un-cushioned by tires—to find food.

After the war, Helena remained in Holland but visited Israel several times, including a 1980 visit during which she and her husband received the righteous among the nations award from Yad Vashem. She lived until she was 97, sometimes visiting the Goldbergs. “I always think even today how she did it all,” says Hester. “How she kept us all alive, where she got the strength from.”

Some righteous among the nations developed personal connections to Jews before or after moving to Israel, and even converted to Judaism. Hester fell in love with a Jewish man on a kibbutz, married him, and opted for conversion “for the sake of our kids.” Other children of the “righteous” ended up marrying Jews. But the right of the “righteous” to live in Israel is automatic and does not require conversion or Jewish familial connections. Many of them have not changed their beliefs and traditions since relocating to Israel.

Jaroslawa Lewicka told her story for this article a few days after Christmas, which she celebrated at a church near her home in the northern Israeli city of Haifa. She took part in services and a festive meal. It was a pot-luck affair, but she feels the need to point out, for the sake of full disclosure, that she didn’t make anything. Her fellow congregants forgave her, since she is, after all, 81 years old.

For decades, Jaroslawa lived under a communist regime that suppressed religion. The city where she lives now is quite a contrast, home to an annual multicultural winter event called Festival of Festivals. “Now I live in Haifa, which is a city of three religions, Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, and I go to a church with a priest who prays in Ukrainian, and no one bothers us,” she says.

Jaroslawa arrived in Israel in very different circumstances than Hester. It was economics, not idealism, that brought her here. In 1989, a man she helped save, Avraham Shapiro, invited her to visit Israel, to meet him after five decades, and to visit Yad Vashem where she would receive a medal as a righteous among the nations. She recalls: “When I was here people started asking me about the economic situation back home and it was very hard, especially as my parents had just died.” She started to find out about state programs that help the “righteous” relocate to Israel, and found that there was only one thing standing in her way: “I couldn’t afford the airfare.” Shapiro stepped in to cover the expense.

Today she has enough money to aid relatives facing harsh economic conditions in the Ukraine. Like others who moved to Israel after saving Jews, she receives visits as well as practical and medical assistance from the Israeli charity Atzum, which has a project dedicated to helping them. “I feel extremely fortunate for the fact I live in Israel,” Jaroslawa says. “I don’t have the words to express it.”

She believes it was Christian faith that pushed her family to hide Jews in their home, help Jewish refugees, and take food to the ghetto of Zloczow near their home. “It’s the Christian faith that motivated me and my mother and also concern for our neighbors,” she comments.

She was only five or six when she started making grocery runs to the ghetto, wearing a backpack with food buried under notepads and schoolwork. She would slip in through a gap in a barbed wire fence. Later, when the gap was closed, she would brazenly enter through the gate when guards weren’t paying attention. “Of course there was fear, but the Germans never hit [non-Jewish] children,” she says. This is why she took responsibility for the food drops: Her mother had been spotted and beaten.

At home, there were several close calls, especially when Nazi officials hoped to make use of children who were too young to fully understand what was going on. Once her father hid a boy under the sofa, and he was there, playing with a toy soldier, while a real-life Nazi officer was in the house, oblivious to the danger he and his hosts were in. The child remarked afterwards that he had been scared “that someone would step on his hand.”

Yael Rosen, one of the most dedicated volunteers helping the “righteous” with home visits and phone calls, finds Peotr Sanevich’s biography one of the most moving. “It’s a story of a deep bond that was rediscovered so many years later,” she says.

For Peotr, moving to Israel was a case of repaying hospitality. He constructed a secret hiding place for two young Jews who arrived on his family’s farm in the Ukraine after narrowly escaping death. He knew what could happen if he helped them: An entire family from a nearby house had been burned for sheltering Jews. But for two years, he and his family kept young Buzya and David safe.

Peotr heard nothing from the Jews he saved for almost five decades. After the fall of the USSR, however, he started making enquiries. In 1993, the Israeli ambassador to the newly independent Ukraine got Peotr back in touch with them. David suggested that Peotr move to Israel and he did, together with his wife Olga, and Rosa, the youngest of his six children. They chose to live in David’s city, Beersheva, in order to be close to him.

The Negev also became the unlikely home of two other rescuers. Deep in the desert lies Yeruham, a small city dominated by the families of Jewish immigrants from Morocco and India. Among them lived Yekaterina Movchan-Panchenko and Galina Panchenko, two Christian widows whose first encounter with Jews came in the 1940s when they helped save two Jewish children from the Nazis.

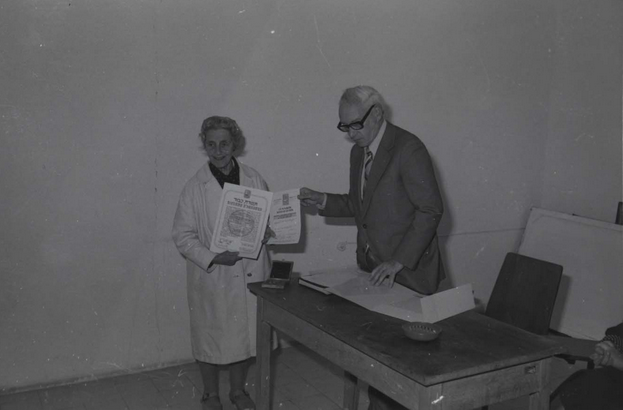

Yekaterina Movchan-Panchenko receives an award honoring the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem in 2001. Photo: Yad Vashem

The mother of seven-year-old Pavel and one-and-a-half-year-old Nina had already been murdered by the time they arrived at the Panchenko family home in what is now the Ukraine. Yekaterina and Galina were just 19 and 11 respectively, but they sprang into action and helped keep the children safe, fed, and healthy.

Police came knocking twice, demanding to see the children, but Pavel and Nina were hidden in the cellar. After surviving the war, the two children stayed in Krivaya Ruda, where they became parents and grandparents. But history took Yekaterina and Galina elsewhere, and shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union they moved to Israel and put down roots in Yeruham, where they lived until they died a few years ago.

Yael Rosen used to work full time with the righteous, directing Atzum’s program to care for them. Even since she moved on to a high-pressure job at a Tel Aviv museum, she still makes visiting them a priority. Asked why, she responds, “It’s a huge privilege to know these people and be involved with them. They risked their lives to save Jews and there’s never enough that we can do for them—anything we do is a drop in the sea.”

She adds, “During the Holocaust, they cast their lot with the Jewish people and now, they’re doing the same again – they are part of the Jewish people in the good times and in the harder times.”

No family knows the reality of this common fate better than the Shuranis. Tzipi Shurani’s parents met under the most unlikely circumstances: Her father was a Jewish prisoner in a Nazi labor camp and her mother lived in a house next door to the fence. Latzi Shurani had already promised himself that he would marry Irena Csizmadia when the two of them dug their way towards each other, fashioning a tunnel that ended in the Csizmadia basement, through which he and more than two dozen other prisoners escaped. They did marry, and lived together contentedly in the Galilee. But when the second of two Hezbollah rockets hit their home during the Second Lebanon War of 2006, Irena suffered a serious stroke and the active golden years that the pair were enjoying were suddenly torn away from them.

Nevertheless, they maintained the love that blossomed in the shadow of hatred. Latzi died two years ago. Irena is today in a home, unable to reflect on her life, but Tzipi says, “I wish every couple could be like my father and mother. They would always hold hands, and go everywhere together.”

When “righteous” who moved to Israel die, their funerals—paid for from state budgets—are emotional and dignified affairs; the starkest possible contrast to the disdainful treatment given to gentiles who the Nazis caught and killed for helping Jews. Rosen recalls the funeral of one of the sisters who lived in Yeruham. “There was a priest conducting the ceremony, other people eulogizing her for saving Jews, and the setting was the Negev where a camel was walking by,” she recalled. “It was very surreal and very moving being in the Israeli desert burying such a special woman from the Ukraine.”

![]()

Banner Photo: Yonatan Sindel / Flash90