For the first time, all remaining bronzes of the Roman emperor Hadrian are being exhibited in one museum. What can they tell us about the end of the last Jewish state?

Among the documents, sandals, jewelry, and coins left in a cave in the Judean desert nearly 2,000 years ago were dozens of iron house keys. Just above this cache of personal items found in what is now known as the Cave of Letters, lay the ruins of an imperial Roman army camp, which occupied and ultimately destroyed Jerusalem and its surrounding Jewish communities one final time during the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt in 136 CE.

According to scholars, these items belonged to Jews who fled their homes during the final violent days of Judea’s bid for independence from Rome. They locked their houses and sought refuge in the desert, hiding in the caves above the Dead Sea until it would be safe to go back home. It never was. “They had the hope to return,” says David Mevorah, curator of Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine archaeology at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where the keys are on display as part of the new temporary exhibit Hadrian: An Emperor Cast in Bronze. “But nobody came out alive.” Centuries later, archaeologists found their skeletons preserved in the dry desert air. These bones of men, women, and children that lay among the keys show just how ruthless the soldiers of the Roman emperor Hadrian really were. The legions didn’t simply assert control over Jerusalem. They pursued, fought, and killed the Jewish rebels and their family members in this remote area, and left others to die of starvation in their desert hideouts. The archaeological team that discovered them in the 1960s—many of whom were veterans of Israel’s 1948-49 War of Independence—bore witness to the devastation that befell the previous attempt for Jewish independence nearly 2,000 years earlier. “Nothing remains here today of the Romans save a heap of stones on the face of the desert,” wrote Yigael Yadin, the archaeologist and former chief of the Israel Defense Forces who led the expedition. “But here the descendants of the besieged were returning to salvage their ancestors’ precious belongings.”

The Bar Kokhba revolt was a major turning point in Jewish history. It was the final crisis that scattered the people of Israel into a diaspora that would last nearly 2,000 years. Yes, the famous destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE, which left the Second Temple in ruins, also sent people fleeing to the diaspora, but the brief attempt to throw off Roman rule in 130 CE was the last straw. Enormous numbers of Jews, both soldiers and civilians, were slaughtered. Many of the survivors were sold into slavery. Others fled a nation that had been decimated by war. It was a loss that completely severed a people from its roots.

As Mevorah looks at the ancient keys on display, he compares them to the collections of shoes and suitcases of Holocaust victims. “It’s a holocaust, and Judaism changes forever,” Mevorah says of Rome’s suppression of the revolt. The Jewish legacy in Israel was also affected, as Hadrian changed the name of the province from Judea to Palaestina in an attempt to erase its Jewish past and the threat it posed to his hold on power. “The Romans never changed the names of provinces, this was a really big deal,” Mevorah explains. “And Hadrian chose to name it after the Philistines from the Bible, who are portrayed as the enemies of the Jews.” Historical sources mention Bar Kokhba and his fight for Jewish independence, but details are scanty, and speculation still continues as to its true cause. The 2nd century Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote that the Jews revolted when Hadrian visited Jerusalem in 130 CE and renamed the city Aelia Capitolina after himself. This led to a Jewish uprising of “no slight importance nor of brief duration.” Roman soldiers, with extra legions sent from abroad, spent four years suppressing the revolt. The war was devastating. The legions destroyed 50 fortresses, 985 settlements, and killed 580,000 fighters and innumerable others who died of starvation and illness. “Thus nearly the whole of Judea had been made desolate,” Dio wrote of the aftermath.

The exhibit encapsulates the continuing quest of the Jewish people to assert their side of the story, to demonstrate their historical link to the land of Israel and the trauma of their long and troubled past.

But the Christian historian Eusebius, a bishop of Caesarea, wrote that Hadrian only changed the name of Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina after Roman troops suppressed the revolt, as a punishment for the Jewish uprising. Hadrian banned Jews from the city and attempted to erase their connection to it through changing its name. “It was colonized by a different race,” Eusebius wrote. Another chronicle on the time, the Historiae Augustae, says that it was a ban on circumcision, which the Roman Empire considered a form of castration, that triggered the uprising. Scholars today are still divided on what exactly triggered the revolt and when Jerusalem was renamed. The Jewish sources include little historical material about the war. Instead, they chronicle a debate on whether its leader should be called Bar Kokhba, meaning “son of a star,” and hailed as a messiah, or Bar Koziba, “son of a liar,” whose power and ambition resulted in calamity for his people at the hands of the Romans.

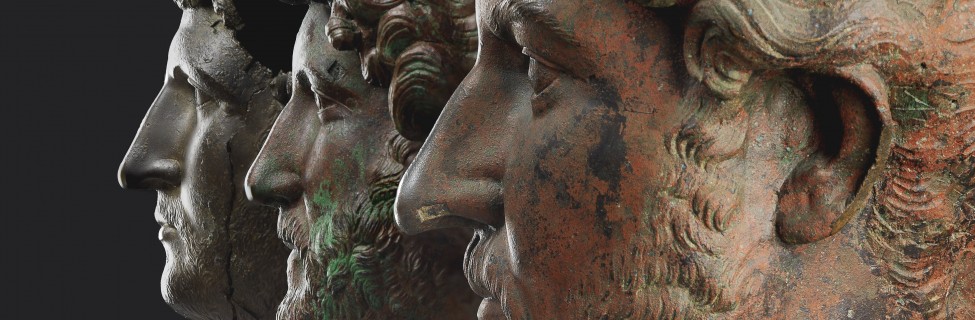

The new Israel Museum exhibit on Hadrian highlights the emperor’s attempt to wipe out the Jewish connection to Jerusalem and the surrounding area. At the same time, however, it shows that this was a black mark on a list of otherwise enlightened accomplishments. Three bronze statues of Hadrian, one found in Israel, one at the bottom of the Thames River in London, and one of unclear origins bought at a Paris antiquities market in the 19th century, are the focus of the exhibit. It is the first time these three statues, the only bronzes remaining of Hadrian, have been displayed together. The subtle differences in the three statues are used to tell the story of the different views on Hadrian and his legacy, particularly the unique Jewish picture of him after the bloody suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt. The Romans saw him as a strong leader who pacified Rome’s vast empire; the Jews saw him as a brutal and murderous tyrant.

“On first glance, the bronze portraits look very much alike, but they are very different,” Mevorah says. Thorsten Opper, the curator of Greek and Roman artifacts at the British Museum and co-curator of the Israel Museum exhibit, notes, “As a group they tell a story that is much more powerful than each one alone.” The idea for the exhibit came in 2008, when the British Museum borrowed the single bronze portrait of Hadrian in the Israel Museum’s collection for an exhibit that examined the emperor’s personal life, mainly a passionate love affair with a young Greek man, and his political and cultural achievements, which included enforcing rather than expanding the empire’s borders and undertaking construction projects like the famed Pantheon in Rome. It was then that Mevorah and Opper got into a discussion about the different ways Hadrian’s legacy is seen. According to Opper, Hadrian is best known for his architecture and for withdrawing from some areas of the empire. “He stopped the expansion of the empire and this says he was more interested in peace than war,” Opper told me. “It was the golden age of the Roman empire.” But back in Jerusalem, Mevorah says, “The Jewish angle is 180 degrees from the other side. He is considered the most violent and cruel emperor. He is remembered as the bone grinder, may he rot to the bone.”

In this way, the exhibit encapsulates the continuing quest of the Jewish people to assert their side of the story, to demonstrate their historical link to the land of Israel and the trauma of their long and troubled past. Does this mean, at least in part, that Hadrian’s attempt to wipe out the Jewish legacy in Israel somehow succeeded, forcing the descendants of Bar Kokhba to continually recite their narrative, even today, to its doubters, to those who see Zionism as just another form of modern colonialism? Perhaps not. The Israeli story of the revolt, now illustrated with archaeological evidence, including the keys and letters from Bar Kokhba found in the caves, and a recently-discovered engraving commemorating Hadrian’s visit to Jerusalem in 130 CE, may be a narrative of ultimate victory. It took 2,000 years, but the Jews finally defeated the emperor they loathed.

“When all the fragmentary tales and traces of Bar Kokhba were assembled they amounted to no more than the lineaments of a ghost,” wrote Yadin, who led the joint military and academic expedition in 1960 that searched for traces of the revolt. “He figured in Jewish folklore more as a myth than a man of flesh and blood.”

But in the late 1950s, that ghost began to show signs of life. Fragments of leather and papyrus bearing Greek and Hebrew writing were put up for sale in the antiquities market in the then-Jordanian controlled Old City of Jerusalem. The sellers were desert-dwelling Bedouins from the Ta’amireh tribe—the same group that discovered the famous Dead Sea scrolls a decade earlier. One of the ancient letters, which the Bedouins said was found in a cave near Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls had been found, was from Shimon Ben-Kosiba, Bar Kokhba’s given name. When news of these documents made its way to Israeli scholars on the other side of the city, a series of expeditions were organized to explore the caves, hoping to find additional artifacts from the revolt before the Bedouins did. Over the course of two weeks in the spring of 1960, an expedition led by the IDF and involving several archaeologists and dozens of volunteers explored 14 square kilometers of the Judean desert. They flew in helicopters through narrow canyons surveying the land, and used rope ladders to enter the numerous caves in the steep cliffs. It was not just a scholarly mission in pursuit of the first actual archaeological evidence of a man named Bar Kokhba. It was a search for a man who had become a hero. With the advent of modern Zionism and the then-recent establishment of the State of Israel, Bar Kokhba’s legend had emerged as an inspiring example of the ongoing fight for Jewish independence.

An image from a 15th-century manuscript depicting the expulsion of the Jews after the Bar Kokhba revolt. Photo: Wikimedia

After days of searching bat-infested caves, the team began to find skeletons, textiles, coins, jars, jewelry, and other household items. Then, tucked in a crevice, they discovered a bundle of papyrus documents. When they were unrolled by experts, the documents revealed numerous writings from Bar Kokhba himself. They included letters to commanders at the Jewish holdout at Ein Gedi, a desert oasis near the Dead Sea, which reveal his authority and desperation as he orders his subordinates to bring more supplies to rebels still fighting the Romans. Other letters show Bar Kokhba’s piety. Even as his revolt was failing, he demanded thousands of citrons and palm fronds for his troops so they could properly observe the holiday of Sukkot. The find, which was the first tangible evidence of Bar Kokhba’s existence, was so significant that it the government’s radio station interrupted its programming to announce the news. “Obviously this was not received as just another archaeological discovery,” Yadin wrote. “It was the retrieval of part of the nation’s lost heritage.”

In contrast to this hunt for traces of Bar Kokhba, the archaeological evidence for Hadrian’s presence in Israel was mostly found by accident. In 1975, an American tourist was walking with a metal detector outside Kibbutz Tirat Zvi in the Beit Shean Valley near the site of a Roman camp, hoping to find ancient coins. When his detector buzzed, he dug about two feet into the ground and found a bronze head. Gideon Foerster, then the Israel Antiquities Authority’s head archaeologist for Israel’s northern region, recalls getting a phone call about the find and rushing to the kibbutz.

“Then, I saw this bronze head of Hadrian sitting on display in the kibbutz dining room,” Foerster told me. “This was 40 years ago, but it’s still a story for me.” He then led an archaeological excavation in the area the head was found. He uncovered another Roman army camp, where troops likely displayed the bronze statue of the emperor. He also found 40 additional pieces of the statue, including muscular shoulders, and an armored chest and torso, showing Hadrian as a military commander. The figure was reassembled and now stands in the Israel Museum as the center of the current Hadrian exhibit. Of the three bronzes of Hadrian on display this is largest one. On the other borrowed bronzes, found in England and probably Turkey or Egypt, only the heads remain. They may also have portrayed Hadrian in military pose, but it is equally likely that they showed him in another aspect, as a god or high priest, as was common around the empire. In the fall of 2014, while undertaking routine excavations, the Israel Antiquities Authority uncovered an inscription bearing the name and title of Hadrian and commemorating a visit he made to the city in 130 CE. This inscription was the missing half of a Latin inscription found in Jerusalem in 1903, which archaeologists could never tie definitively to Hadrian, because the first half lacked his name and the date. Hailed by the Antiquities Authority as “one of the most important” Latin inscriptions ever found, it confirmed Cassius Dio’s written account of Hadrian’s fated visit to Jerusalem and that the city was still called Jerusalem at the time. Although this is the first concrete evidence of Hadrian visiting Jerusalem, it is still not clear when he renamed the city Aelia Capitolina.

But maybe this chicken-or-the-egg question does not really matter. What matters is the violence of the struggle between Rome and Judea, and the resulting absence of a Jewish majority in the land of Israel. This turmoil is embodied in the ancient iron door keys, saved but never used again, which now sit in a glass display case. But the three larger-than-life bronze statues of Hadrian dwarf these remnants of Jewish life in Israel. “With all due respect to ourselves, we are a very small province at the east end of the empire, so the revolt is not remembered,” Mevorah says. Co-curator Opper says that the fact Hadrian suppressed the revolt, and maintained control and stability in the empire, is the reason historical sources do not elaborate on it. “It’s not treated as a major aspect of his reign,” Opper said. “Overall it was a time of great peace and prosperity in the Roman empire.” Opper only saw the keys and other items recovered from the caves for the first time in 2007. “I didn’t know much about the Bar Kokhba revolt, except from books,” Opper said. “For me, it was immensely powerful to see these keys and other objects. You can just imagine these people holding the key in their hand, locking the door and not coming home. That is incredibly powerful.” While these keys belong to the victims, and show the failure of Bar Kokhba’s rebellion, their discovery and display are a Jewish victory. They are illustrations of the ancient story of a Jewish state in this land, and they remind us that Rome is now dust, while that Jewish state has been resurrected. “Bar Kokhba has…become a great hero,” Foerster says, “and here we are today.”

![]()

Banner Photo: Elie Posner / The Israel Museum