Why do Israeli parents give their kids independence while American parents live in perpetual fear? Maybe because the violence in Israel is much easier to explain to children.

When my husband and I moved to Israel with our two children for a year-long sabbatical, we could never have expected that the first four months of our stay would be bookmarked by two shattering acts of violence. In October, our sons learned what it means to be trapped in the school bomb shelter as rockets fell around on the country. Then, at the end of December, twenty small children in Newtown, Connecticut, were shot dead at school by a young man armed with a semi-automatic weapon. Our children, who are 7 and 9, were so deeply rattled by the first episode that we tried to shield them from the second.

I had no illusions when we made the decision to spend a year in Israel that our kids wouldn’t have to contend with the possibilities and realities of violence in all kinds of new ways. I’d lived in Israel as a child and I knew the drill. You can’t walk into a supermarket here without having your bag searched by an armed guard, and you can’t sit on a public bus without getting poked in the rib by a soldier cradling her M-16. During the first week at his new school here, my son bid the armed guard who stands in front of the building’s locked gate a cheerful “shalom hamoodi,” or “goodbye cutie,” suggesting he’d already normalized the presence of the gun.

When we’d begun telling people we were coming to Israel for the year, many of them asked outright how we could possibly expose our family to the rampant violence of the Middle East for a year. What we didn’t often express in response was how uncomfortable we had become exposing our family to the rampant violence of the United States. This is violence expressed not so much in the ongoing threat of terror attacks, but in wave after wave of public shootings, in the media our kids consume, and in the ways we talk to one another in the media.

We like to pretend that violence in America is limited to “bad” neighborhoods and military interventions. But that minimizes all the others forms violence has taken in our children’s short lifetimes, from U.S.-sanctioned drone strikes, to casual acceptance of torture, to global warming, to “revenge porn,” to school bullying and corporate self-dealing.

To be sure, many of these phenomena exist worldwide, but for my husband and me, our growing sense that we were living amid such profound, if repressed, violence made the prospect of removal to a nuclear Middle East seem like something of a peaceful retreat.

One of the ironies about raising children in Israel is that they have far more independence here than they ever would at home. Since their birth, we’ve been obsessed about giving our children the gift of independence. Even a casual comparison of the independence we enjoyed as children thirty years ago with the anxious, overinvolved parenting we do today had us worried that without reasonable independence, our sons could not properly develop.

We read all the statistics about the chances of our kids being the ones to be stuffed in the back of a van by a stranger (low) and the ways in which the fear of everything — despite those statistics — has driven American children and their parents to live largely indoors, and, increasingly, in front of screens that occasionally show life outdoors in video game format (often with the purpose of shooting at it).

Our growing sense that we were living amid profound, repressed, violence made the idea of taking our kids to the Middle East seem like a peaceful retreat.

We decided a long time ago that we’d let our kids walk to the park around the corner from our home in Virginia. (We convinced dear friends to do the same, and when they did, the police called and told them to come collect their seven year old.)

So when we got to Israel we took the decision (perhaps foolishly) to allow our children to walk the twenty minutes across busy streets home from school, to allow them to play in the park unattended and to let them stop at the store to buy their own treats. Israel is basically kid-land anyhow. Never have more candies been more cunningly manufactured to be stuffed into small mouths. Israel worships its children. They practically run the place.

After the school day ends, Israeli kids pretty much universally fan out helter-skelter to all sorts of clubs and lessons and scouting activities, and as far as any parent can tell, they could all be out laundering money or selling stolen furniture off the backs of trucks. Israeli parents allow their children all this independence despite the security worries either because they are PTSD-suffering existentialists or because they don’t feel they’re in danger.

I am starting to suspect it’s the latter. Despite the security guard at the school gate, the sirens last October, and the fact that I’m told that we might very well be living in Jerusalem at the start of the Third Intifada, I believe my children are safe here most days and in most places. (And before you remind me that I live in a country with a fence, I’d just like to respond that, yes, I know, and so do you.) But my worry isn’t about violent terror so much as the terror of violence — and those are, interestingly enough, two very different things.

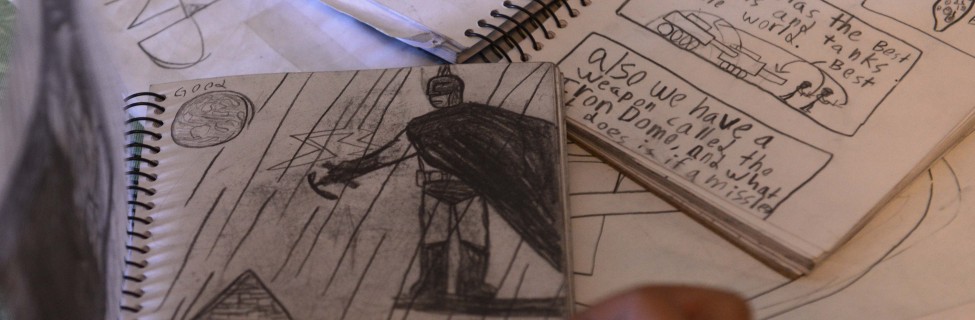

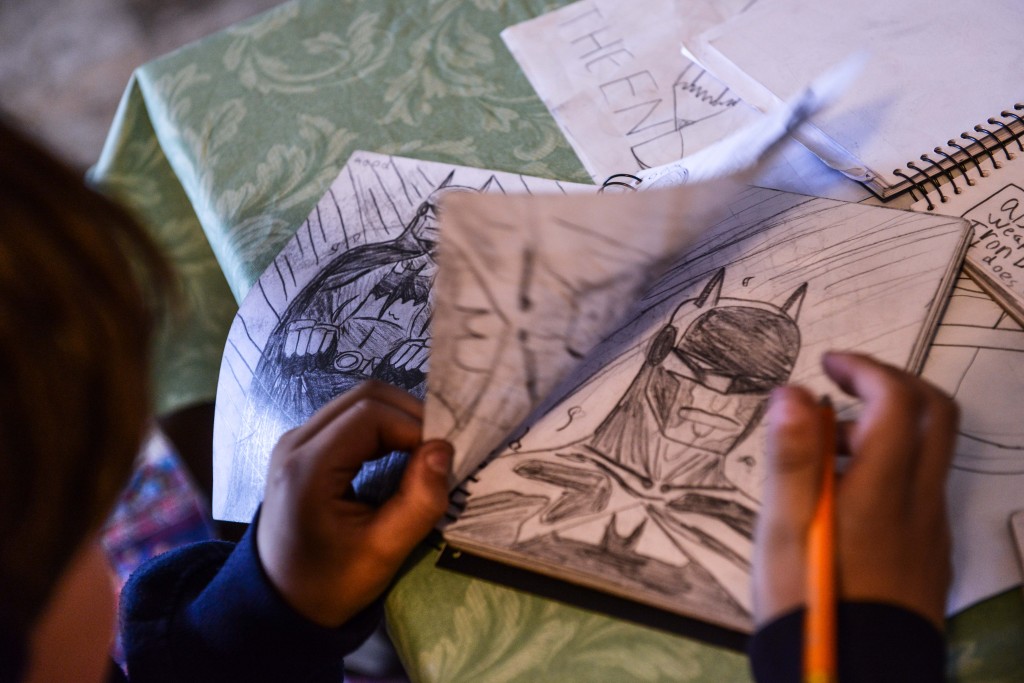

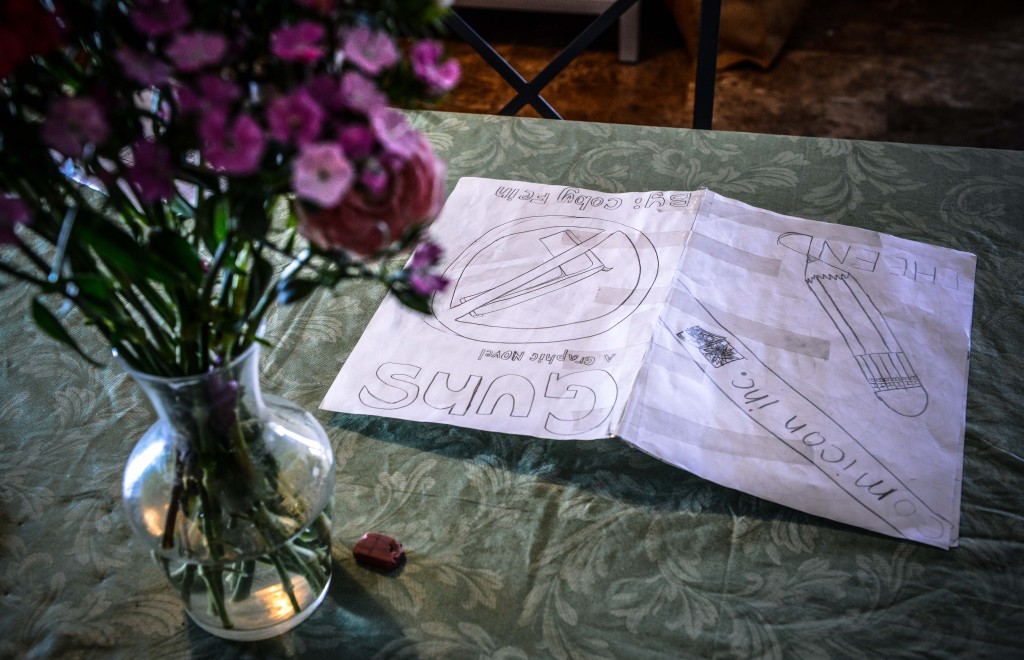

My older son has been cartooning almost since he could hold a pencil, and when he’s stressed he draws. I’m grateful he has the outlet because his drawings usually calm him, though they’ve been known to terrify me. But maybe that’s why I’ve come to look at the two comic strips he produced this past fall about Operation Pillar of Defense and Sandy Hook, as a kind of Ur text about childhood and violence, at least as it pertains to my family.

I keep going back to his drawings and trying to calculate the incalculable: Given that we all live in a dangerous and violent world, what is the rational distribution of fear and danger to which one can reasonably expose one’s children? At what point is having fearful children, and living in constant fear for your children, sufficiently debilitating to warrant fundamental changes in your life?

Am I afraid to bring my children back to the U.S. because there was a man stopped at the grocery store near my house in sleepy Virginia, with an AR-15 in his hands this January? (He was, of course, not arrested because it’s not illegal for civilians to carry semiautomatic weapons into Virginia grocery stores). I am.

And yet, everywhere I go I see guns in Israel, but the prospect of my sons walking past the cheese counter at the local Kroger and bumping into a guy with an AR-15 leaves me breathless with fear. I suspect that this is at the core of my current “rational violence” obsession. In Israel, a country literally teeming with guns, I have no fear of being spattered all over the blue cheese at the grocery store.

As best as I can now discern, the only way to know whether an American civilian armed with an assault weapon on the street is a Second Amendment performance artist, a “Stand Your Ground” defender of his home or a Columbine-style mass shooter is just to wait until he’s opened fire. This strikes me as a rather risky calculation, and not one I am comfortable leaving to my children to sort out.

I’ve never really experienced terrible acts of violence and – as I quickly discerned in law school – by some lights that means I am not entitled to voice opinions on the subject. The “you don’t understand” debate that rages about guns in America is dominated by victims and gun owners. The rest of us are deemed too naïve to really understand the issues, even though it’s becoming ever more apparent that we are all victims of violence in America, whether or not we have the bullet holes to show it.

But living in Israel has taught me that no matter who – or where – you are, managing violence is largely a practice in selective repression. My in-laws in New York were terrified that we were in danger during the rocket strikes last fall. We told them to turn off the TV because we were nowhere near the danger zone. We called my parents in the south of Israel and told them we were terrified for them during the rocket strikes last fall. They told us to turn off the TV because they were nowhere near the danger zone.

Israelis find the tendency of Americans to go on random fame-seeking gun rampages absolutely horrifying. Call it a paradox. It’s hardly heaven here, but absent a handful of well-publicized gun assaults, like the one that killed Itzhak Rabin, Israeli guns are locked down by the government – and Israelis like it that way.

More profoundly, there is a gaping cultural divide in the ways Americans and Israelis think about guns. For Israelis, guns are simply not – at least not yet – a mechanism whereby disaffected and isolated attention-seekers can gain instant fame and permanent recognition. Israelis use reality TV for that. But disaffected maniacs aside, one thing about Israel and violence is undoubtedly clear, and that is Israelis do not consider the ownership of assault rifles to be the lone bulwark against government tyranny.

When I hear the litany of American voices claiming that they, as individuals, can and will take on both deranged gunmen and overreaching government with their personal firearms, I’m reminded of nothing so much as the argument around the time of the Obamacare debate: that real Americans don’t need health insurance either, because in the event of a ruptured kidney they can just thread a needle and sew the thing up themselves. It’s astonishing that so many Americans are able to believe simultaneously in their inviolable personal fortitude when it comes to their health and their boundless vulnerability when it comes to violent crime. It’s an impressive mental trick, but somehow we manage to pull it off.

As I continue to deconstruct my son’s cartoons about his new experiences with violence, I find myself cycling through more questions than I can reasonably answer: Isn’t violence simply a part of a child’s life? Indeed, isn’t violent fantasy a psychologically vital part of a child’s development? Isn’t the real problem the media that renders every violent event on the planet a festival of coverage? Isn’t it the case that if I lived in a jungle I would hear daily reports of children being eaten by tigers and be equally terrified as a parent?

And ultimately, isn’t this all just a trivial actuarial debate anyhow – an effort to guess whether children are at greater risk from cars, guns, fundamentalist terror, or sexual predators? (Of course, if that is the only inquiry, the answer will always be: cars.)

So actuarial calculations notwithstanding, I suspect this is my thought: If I can’t engineer a perfectly safe world for my children (and probably wouldn’t want them to live there even if I could), perhaps the best I can do is help them understand why the world they live in isn’t safe. Perhaps I can at least tell them a story that explains it. Although the bloodshed over the Middle East is at its core irrational and heartbreaking, at least I can help them understand why it’s happening and explain to them how to turn their hands toward healing it.

If I can’t engineer a perfectly safe world for my kids, at least I can try and help them understand the dangers.

Every day at the park near our apartment, my kids see little Arab kids, as well as ultra-Orthodox, secular and modern Jewish children playing on the same swings. Every week we see interactions between races and religions and cultures that belie the popular image of the Middle East as polarized and aggressive. For every act of violence they have seen since they’ve been here in Israel, my sons have seen as many, if not more, small acts of repair.

But what I cannot explain to my children, or myself, is why a young man would walk into a school and shoot kindergarten students, or why a nation that could do something about it would decline to do so. I can’t explain why their fellow citizens won’t agree to simple fixes in gun registration and sales laws that could save thousands of lives, or why anyone anywhere needs a gun that can kill dozens of people in under a minute.

I can’t explain to my children why we use all the power and authority of our modern wealth and technology to threaten and shame and frighten one another instead of trying to resolve the problems of violence. I look at my son’s comics and I can construct a story about the first one, but am unable to say anything about the second. I can’t explain to them why Sandy Hook happened, or why some people deny that Sandy Hook happened. I can’t explain why the grieving parents and heroes of Sandy Hook have become the recipients of hate mail and threats. And I can’t explain to them – and I’m afraid to even try – why in supporting gun control, their mother has also become the recipient of hate mail and threats.

Here in Israel, the violence and the threat of danger are all too real. Back home, imaginary armies of imaginary soldiers coming to seize one’s guns somehow warrant violence – or at least the constant preparation for it. From here, I’ve seen the extent to which imaginary violence met with utterly deranged violence utterly defies rational explanation. Violence fed by the media and celebrated by the media and ultimately rewarded by the media is not rational violence.

One of my working worries about violence in America is that it is driving us toward paranoid insularity and clannishness. Yet I sometimes fear that my feeling of safety here in Jerusalem is itself a product of insularity and clannishness. Certainly I would feel very differently living here if I were a young Palestinian male. My definition of “rational violence,” after all, comes down to an acceptance of the kinds of violence that people in this region (like in many places around the world) have perpetrated against each other for thousands of years – the violence of tribe and religion.

Maybe the distinction is that this type of violence is less rational than familiar. But more and more it strikes me as something utterly different – both in character and in kind – from the bleak nihilism of the violence I see being wrought back home. Though the difference between living in a region of deep ideological and geopolitical conflict and living in a safe country that has made peace with random, recreational violence might seem subtle, as a parent they are worlds apart. Nobody wants to raise children in a scary, violent world. But at the heart of the casual new American acceptance of violence, I see only emptiness and isolation. And that might be the scariest kind of violence of all.

![]()

Banner photo: Aviram Valdman