Targeted for humiliation, prohibited from observing her religion in freedom, Annika Hernroth-Rothstein tried to draw attention to the plight of Sweden’s small Orthodox Jewish community—and that’s when the trouble really began.

A few months after I had entered high school, the boys with the boots showed up. I called them that because they had paired their historically accurate Hitler Jugend uniforms with shiny 10-hole Dr. Martens, white laces dramatically contrasting their perfect oxblood shade.

I could always hear them approaching, the boys with the boots. The sound of rubber soles against linoleum would cut through the noises of my high school hallway and as soon as I turned around, there they were.

My family had settled in that sleepy coastal town some 70 years earlier, leaving the big city for a better place to raise a family. The war came, and what happened after that I only know through scattered pictures and hushed-down questions. I was told life had become difficult, so they adapted, as the children of their children would also be taught to do.

A year ago, to the day, I went to a foreign policy conference in Washington, DC, to attend a lecture by a State Department official who specializes in countering anti-Semitism. I had come there to ask for help, and when I asked this man whose job is to monitor and combat this scourge of hate around the world what the administration was planning to do about the European crisis, his response to me was that this is not 1939 and while the situation may be dire, the sky is not falling.

As we went around the room and I stated my name he smiled and acknowledged me as the Swedish girl who applied for asylum in my own country. Funny, he said. You don’t look like any refugee I’ve ever seen. The crowd erupted in laughter, and I sat silent, waiting to be clued in on the joke. I had come to tell my story, but the man in front of me did not really listen, and as I would later learn, neither did the world.

That was one year ago. A year of writing, fighting and sounding the alarm, and each time there was another isolated incident I told myself that this must be as bad as it gets.

Each time I was proven wrong.

The boys with the boots would talk to me sometimes. Without a hint of aggression they would tell me that my relatives had become soap in camps, not too far away from where we stood, and that I should follow suit. There was no physical violence, not even once. Instead they would sit next to me in the cafeteria, wait for me at the top of the stairs, or stand to attention as I passed by them. I didn’t know why they despised me, but I knew that it mattered. It mattered to them, and so, it had to matter to me.

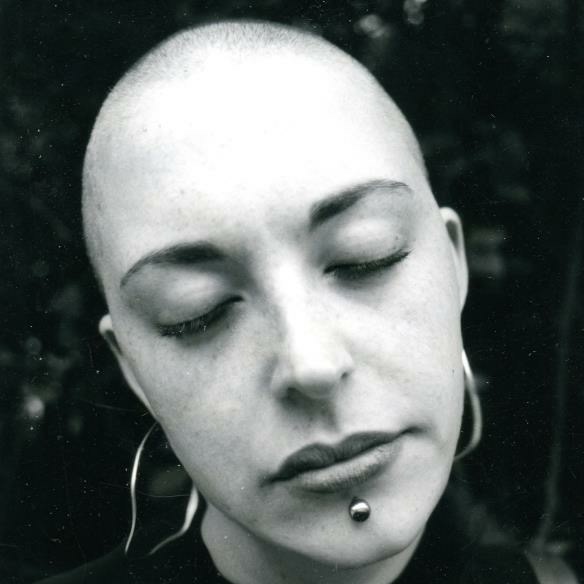

When I was 15 years old I shaved my head. It was a last resort, a final measure, after spending years changing for and adapting to a world that seemed set on viewing me as a stranger. I had tried so hard. Taming the wild, dark curls, bleaching and straightening to resemble the shiny blonde girls. It didn’t help; neither did hiding in bathrooms and libraries to escape the silent warfare that recess had come to be. It was as if the more I altered myself to be like them, the more they despised me for even trying.

The whole process took over two hours, and when I finally met my own gaze in the bathroom mirror I could see that the venture had been in vain. All the traits I had grown to despise—the big nose, the wide mouth, and the bushy black eyebrows—were all the more visible without the aid of an untamed hair. That was the night I realized there was nothing I could do to change what made me deserve all this hatred. It was also the first and last time I ever saw my mother cry.

In the past two years, Europe has exploded, from gruesome murders in Belgium and France to riots, torched synagogues and defaced Holocaust memorial sites, along with a dramatic spike in hate crimes all over the continent. Jews are being singled out and persecuted, once again, and most recently Paris and Copenhagen were added to the list of cities synonymous with terror, as more Jewish blood was spilled before the eyes of the world.

Some would say this summer changed everything, but the situation for European Jewry was dire well before Operation Protective Edge created open season on us and the link to Israel came into question for Jews across the continent. There is nothing new about the anti-Semitism we see now, but the dormant hatred seems to have reached critical mass, using anti-Zionism as a handy and creative outlet. I experienced this shift firsthand this past summer as I traveled from Sweden to Israel during the war. I had had the audacity to display the Israeli flag on my luggage, and that gave someone handling my bag enough reason to rip off the flag, stab the bag and its contents several times, and then pour soda onto the precious siddur that goes with me everywhere. No matter what the airline officials tried to tell me, this was no accident, nor was it political commentary. It was terrorism, having been given the excuse to move above ground, into broad daylight, without any pushback or consequence.

My mother sat me down and told me that once, when she was just a little girl, she had gone driving with her father. Suddenly she had asked him what it meant that they were Jewish, and why all the children at school were telling her that she was. Her father had slapped her across the face and yelled, “Don’t ever say that word again! If anyone asks, we are Walloons. That’s what you tell them. Walloons.” They rode back to the house in silence, and my mother did not broach the subject again.

Residents of Malmö, Sweden’s third-largest city, protest a Davis Cup tennis match against Israel, March 7, 2009. Photo: Andreas Blixt / flickr

The terror that haunts the Jews of Europe is not a local one, but part of the global war that is now killing the Christians of Iraq, Yemen, and Syria and displacing, raping, and torturing minorities all over the world. When concessions are made toward Iran, when the Muslim Brotherhood is treated as a reliable partner, when moral relativism is used in dealing with Hamas, gas is poured on the fire that is scorching the earth beneath our feet. The walls have come down, as President Obama so eloquently put it in his 2008 speech in Berlin. For better and for worse, everything is connected and the web woven in the hills of Afghanistan traps Jews in a kosher supermarket, thousands of miles away.

A few weeks ago my son didn’t come home from school at four o’clock, as he always does. I tried his phone, with no answer. I would have tried his friends, but he’s been keeping to himself. The hours passed and just as I was about to call the police, he walks in, breaking down in tears before his bag even hits the floor. He tells me he had joined a few boys to play soccer after school, and everything had gone well until there was a dispute over the rules, and then the group had turned on him. The leader, a classmate of my son, had said, “This is why I don’t play with the cheating Jews.” My son had looked to the rest of them to protest, to stand by him in any way, but instead they had left him to make it back home alone.

Hearing my son speak I felt anger, yes, but also a deep sense of resignation. My great-grandparents came to this country as the Other, almost 200 years ago, and it seems as if not much has changed. The sound of rubber soles against linoleum echoes through each generation, and now they had come for my child.

The State Department official said he knew me as the girl who applied for asylum in my own country, and to him it may have seemed like a joke. But to me, this was anything but. I used this desperate measure in order to make my government live up to its responsibility to protect my right to live a religious life, to preserve my cultural identity, and to allow my children and I to be who we are without fear of persecution. Kosher slaughter has been outlawed in my country since 1937, and a bill is now pending in parliament that would ban even the import and serving of kosher meat in spaces partially or fully funded by the government. Circumcision is also under threat; it is one of few issues in Swedish politics where the Left and Right find common ground. In Sweden today, home to 15,000 Jews amidst a national population of roughly nine million, publicly displaying Jewish identity through symbols or dress means putting yourself at risk of verbal or physical harassment. Synagogues are heavily guarded and Jewish children play behind bars and heavy metal gates. My government has failed the Jewish minority, as they failed my family for generations, so I turned to the world out of anger and sheer desperation.

I believe that the state of a society can be judged by how it relates to its Jews, as we have always acted as the canary in the coal mine for all of Western civilization. What you read about in the news are no isolated instances of violence, no random bunch of folks in a deli, and no simple conflict between countries. This is a historical clash of civilizations, and everything I have done in these past years have been attempts to find out on which side of that clash the world is choosing to stand.

This was not the first time my son had been singled out as a Jew, nor will it be the last. From bullying at school to armed guards at his synagogue, he knows to equate Jewish life with fear and a lingering threat of violence. This is a given for any Jew in Europe, and it has taught us all to alter our lives to deal with this reality. But the events of the past year have driven us beyond the point where alterations keep us safe. The eye of hate has been fixed on us and there is no longer a place to hide.

The State Department official in Washington insisted that this is not 1939, and while he may be right, his use of the Holocaust as the litmus test for persecution allows new and evolved forms of anti-Semitism to fly well beneath the radar. Human rights violations should not have to be quantified. The reaction to these violations should not be dependent on their likeness to other crimes. Nor should any lack of likeness be used as an excuse not to act. It may not be 1939, but the sky is falling and Jews are, in record numbers, making the choice between flight and assimilation, neither choice guaranteeing safety. This is a question of neither chronology nor ideology, but of the universal truth that freedom and fear, justice and cruelty, have always been at war, and that we in the name of human decency must never be neutral between them.

Shortly after U.S. forces liberated Buchenwald, the inmates put up handmade signs with the words “never again.” Since then, those two words have become synonymous with the promise made by the world to remember how we got there, vowing never to return. But now, a mere 70 years later, the promise of eternal remembrance has turned into a strategy of doing nothing until it is safe to say that there is nothing left to do. In 1914, Europe was home to 10.5 million Jews. Today, there are 1.5 million, and the ongoing pogroms are causing 29 percent of European Jews to contemplate emigrating—no longer trusting that anyone in the Diaspora is willing to help them. I am one of those Jews, having to give up on the dream that spurred my great-grandparents some 200 years ago. So, while we may utter the words “never again,” they are not an all-encompassing incantation, nor do they apply only to circumstances identical to those we’ve already experienced. “Never again” does not merely mean never again allowing another Holocaust, but never again being blind to evil, no matter what form it may take. Remembrance is not simply a phrase, but an action, and a solemn responsibility.

Just last year I got it in my head to find out what became of the boys with the boots and the blank, icy stares. I was hoping against hope that they were crawling on the underbelly of society and that somehow the world would make sense again if only their life would reflect the terror they caused me to feel. But of course that wasn’t the case. The boys with the boots are fathers, businessmen, and local politicians. Someone loved them enough to be their wife; someone looks to them for guidance and support. They are not broken, nor are they lost, and there would be no righteous conclusion to my story.

As I was comforting him, my son asked me if we could just stop being Jews. It’s too hard, he said, and I just want it to go away. With those words, I felt as if I had fallen through a black hole into history. We have had this talk before, I have cried these tears before, the hatred may be wearing a different outfit now but the death we are dying is no less dark.

I teach my children about right and wrong, trying to instill in them a faith in good always triumphing over evil. To me these are no fairytales, but values to live and die for. As I write this, I wonder if the world still believes in these ancient truths, and if there is anyone willing to keep the promises made at the gates of hell 70 years ago. If not for the Jews, then because this is an attack on each and every one of us, where we as Jews merely act as a first line of defense in a war that won’t subside once we’re defeated.

I now travel with a plain, black suitcase, and my children are no longer allowed to walk outside with any visible Jewish symbols. These may seem like small choices to some, mere adaptations, but it’s the small things that eventually get to you. It’s the many small details that, stitched together, create a chain of fear that ties you to the ground.

![]()

Banner Photo: Miriam Alster / Flash90