Through his reinvention of the story of Harry Truman’s recognition of Israel in 1948, Judis attempts to overturn the foundations of liberal American Zionism. Only one problem: His version is based on bald distortions and troubling omissions.

Can mainstream American liberalism be turned against Israel? The radical Left in America, as elsewhere, has long been hostile to the Jewish state, but the radical Left counts for little; witness the reception given to Goliath, a screeching diatribe against all things Israeli by professional angry-young-man Max Blumenthal, a former blogger for the pro-Hezbollah newspaper Al-Akhbar. (The former U.S. ambassador to Lebanon put it: “Al Akhbar will no more criticize . . . Hassan Nasrallah, than Syria’s state-run [media] would question . . . Bashar al-Assad.”) Released in late 2013, Goliath was panned in a few Jewish publications and extolled on a few more Israel-bashing websites; including that of David Duke, former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, which called it “extremely valuable,” while decrying its silence on “Jewish domination of the United States.” But almost everywhere else it was simply ignored—except in the Left-wing The Nation magazine, which had to take notice since it published the book. Tellingly, however, The Nation published a pair of sharp rebuttals by regular columnist Eric Alterman, assailing the book and its author’s “analogizing of the behavior of Israeli Jews to that of the war criminals who led Nazi Germany,” and calling it “the ‘I hate Israel’ handbook” that “could have been published by the Hamas Book-of-the-Month Club (if it existed).”

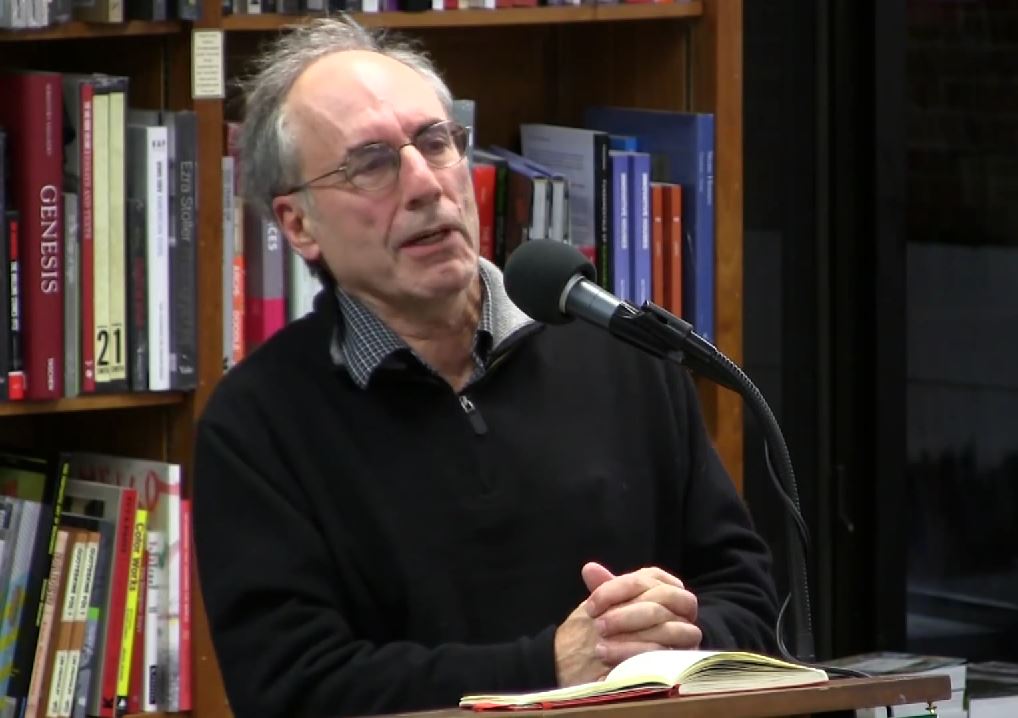

A more formidable assault on America’s pro-Israel consensus is the recently published Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict by John B. Judis. Judis is also a man of the radical Left, having begun his career in the 1960s as an editor of the journal Socialist Revolution, a legacy he reaffirmed in 2008. “A decade ago, I might have been embarrassed to admit that I was raised on Marx and Marxism, but I am convinced that the left is coming back,” he wrote, explaining that the current economic downturn has proven “the transient… nature of capitalism.” In contrast to Blumenthal, however, Judis has absorbed the canons of journalistic and scholarly writing, and has for years been a senior editor ofThe New Republic. America’s premier liberal magazine, TNR counts the likes of John Dewey, John Maynard Keynes, and Reinhold Niebuhr in its pantheon of contributors. Judis’ beat is contemporary U.S. politics, not grand theory; thus, whatever his deeper ideological convictions, his opinions command a respectful audience in liberal discourse.

Moreover, The New Republic is not merely an iconic American institution, it is also—or was from 1974 to 2012, when it was owned by centrist liberal Martin Peretz—one of the brightest beacons of American Zionism. Thus, a frontal assault on Israel’s legitimacy from the pen of a TNR editor, excerpted in the magazine’s pages, signals the loss by Israel’s defenders of a major redoubt. If Judis’ book is understandably being given a more serious hearing than Blumenthal’s, its thesis is not that different: Namely, that the existence of Israel is wrong.

The book is at once a thundering moral judgment, a historical recitation, an exposé, and a guide to future U.S. policy toward the Israel-Arab or Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Judis’ moral judgment is that the movement for a return to what Jews believe is their ancestral homeland was inherently a great mistake and injustice. “Zionism, rooted in the Old Testament, rested on a mythic version of Palestine,” he writes. “In historical terms, the Zionist claim to Palestine had no more validity than the claim by some radical Islamists to a new caliphate.” In contrast to the Jewish attachment to this land, which according to Judis was devoid of truth and right, that of the Arabs was profound. They “lived in Palestine for 1,300 years,” Judis tells us on one page, and—strangely—“1,400 years” on another. “These Arabs,” the modern Palestinians, “trace their lineage in Palestine to 638 C.E.,” and perhaps much further: “There were at least two groups of people in ancient Palestine—the Canaanites and the Philistines—from whom some Palestinian Arabs may have descended.” It is not that Judis objects to some Jews’ desire to live in Palestine, however benighted their motivations. What he finds objectionable was their goal of having a state. He invokes, curiously, Ahad Ha’am—who was hardly anti-Zionist—to pronounce his blessings on the idea of a non-sovereign center devoted to cultivating Jewish culture (not that this culture holds any interest for Judis himself). Thus, he speculates,

One could have imagined Palestine evolving somewhat differently… as a majority Arab state with a vibrant Jewish minority. Such a nation would not have been free of conflict, but it might have nurtured the strengths of both peoples instead of putting them irrepressibly at odds.

But, alas, “Any chance of doing that was probably dashed by the issuance of the Balfour Declaration,” which expressed British support for a “Jewish national home” in Palestine. In short, he writes poetically, “The British and Zionists had conspired to screw the Arabs out of a country.” Thus,

the moral contours of the early history are remarkably clear. From the 1890s, when Zionists first settled in Palestine with the express purpose of creating a Jewish state where Arabs had lived for centuries, until the early 1930s, the responsibility for the conflict lay primarily with the Zionists. They initiated it by migrating to Palestine with a purpose of establishing a Jewish state that would rule the native Arab population.

And what about after the early 1930s? “The rise of Hitler… altered the moral balance,” allows Judis. But, even then, nothing changes in his calculus. While “the right of Europe’s Jews to seek refuge in Palestine had been strengthened,” nonetheless, “the Jewish right to rule Palestine’s Arabs was as tenuous as ever.” While in some minds the annihilation of European Jewry buttressed Jewish claims, to Judis it made a weak case weaker. “The Holocaust,” he claims, “undermined the argument for a state in all of British Palestine…. Zionists had assumed that millions of European Jews would migrate to Palestine after the war, but now there were only several hundred thousand.”

Judis’ historical narrative, where it is not outright erroneous, is marked by the tendentiousness of someone with an ideological ax to grind. For example, he usually describes Arab violence in low-key terms, and mostly explains it as a response to Zionist actions; whereas Jewish violence repeatedly seems to amount to wanton brutality.

The Arab riots of 1929, for one, are presented as being triggered by Jewish provocation. The Palestinian leader, Haj Amin al-Husseini, writes Judis, “was not trying to start protests, and certainly not a riot, but… when Zionist groups began to claim that the [Western] wall was theirs, Palestine’s Arabs took to the streets.” Omitted is the fact that Jewish claims were voiced peacefully, while the Arabs quickly turned to brutal violence. Judis does note that “In Hebron, Arab mobs killed between 65 and 70 Jews and in Safed 18 Jews were killed,” but the whole affair seems to come out rather even. “Overall, 123 Jews were killed and 116 Arabs—the latter primarily by British police.” This anodyne summary contrasts with that of Sir John Chancellor, the British High Commissioner, who reported “acts of unspeakable savagery” being “perpetrated upon defenseless members of the Jewish population regardless of age or sex.”

Not that Judis is incapable of vividness. When he recounts the massacre at Deir Yassin, the most infamous Jewish atrocity of the war of 1948—committed by the Right-wing Etzel militia and condemned by the mainstream Zionist leadership—the detail is hair-raising. Then he adds,

What was particularly shocking about Deir Yassin was that the villagers were, to all intents and purposes, neutral in the war. They were like the Orthodox Jews of Hebron and Safed, many of whom were opposed to Zionism, whom the Arab rioters slaughtered in 1929.

Here, in bracketing Hebron and Safed with Deir Yassin, Judis uses the word “slaughter,” an evocative term that he fails to employ 200-odd pages earlier when presenting the events of 1929. But the comparison is a sly deception. The victims in Hebron and Safed had been unresisting, and Judis wants readers to believe the same of those at Deir Yassin. This omits—indeed, one could say it covers up—details provided by historian Benny Morris in his book 1948, whose authority Judis invokes on the very same page. Morris noted that “irregulars from the village reportedly fired on West Jerusalem and participated in the battle for al-Qastal.” In short, they may not have been so “neutral,” and neither were they unresisting, as Morris relates,

As the attackers moved in, they encountered unexpectedly strong fire from the village’s stone houses and were repeatedly pinned down…. The attackers suffered four dead and several dozen wounded, including the operation’s commander. It quickly emerged that the fighting had been accompanied, and followed, by atrocities. In part, these were apparently triggered by the unexpectedly strong resistance and by the (relatively) high casualties suffered by the attacking force.

In the aftermath of the 1948 war, Judis writes, “Jewish refugees from Iraq and other Arab countries, who became subject to persecution in retaliation for what had been done to the Palestinians, poured into Israel.” But the apogee of this persecution was the pogrom in Baghdad (and other Iraqi cities) on June 1-2, 1941, triggered by Britain’s ouster of the Nazi-allied Rashid Ali, who had seized power a couple of months before. Claiming hundreds of lives, it permanently demolished the security of Iraq’s large and ancient Jewish community. If the perpetrators were motivated but what Jews would do to Palestinian Arabs seven years later, it was apparently revenge in advance. Judis’ recapitulation of various failed peace efforts is as tortured and misleading as his rendition of Jewish-Arab violence. He reports the mufti’s rejection of compromise in the 1930s, but he mostly presents the Arabs as seeking accommodation only to be rebuffed by the Jews. London “might have forged a compromise between Jew and Arab—after the Wailing Wall riots—but Zionists… dashed any hopes of accommodation,” he writes. Then, in 1935, for “the last time… Arab leaders offered a compromise solution.” And that might not have been the end of Arab efforts at accommodation. In the aftermath of World War II, Judis reveals, “The Arab leaders might even have eventually accepted a small Jewish state.”

Haj Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, meets with Adolf Hitler, 1941. Photo: Bundesarchiv / Wikimedia

Judis offers no evidence whatsoever for these assertions, and most respected accounts of those years mention no such conciliation by the Arabs. Perhaps Judis’ perceptions are explained by his view that every diplomatic initiative that would have denied the Jews a state was a true opportunity for peace, while proposals to partition the land to create two states for two peoples were justifiably refused by the Arabs as “fatally flawed” or “unfair.”

So why did the United States end up supporting the Jews? The answer, of course, is the “Zionist lobby.” Judis goes so far as to make the ugly assertion of dual loyalty, impugning the Zionists’ fealty to America. “By spreading falsehoods and distortions about an important foreign policy issue, [Abba Hillel] Silver and the [American Zionist Executive Committee] did American democracy a disservice,” he writes, pressuring President Harry Truman into violating his convictions. Truman “accede[d] to the Zionists’ pressure—not because he believed in their cause, but because he was worried about Democratic losses in 1946 and again in 1948.”

How is Judis able to read the former president’s mind? He offers a variety of quotes in which Truman criticized the Jews and expressed preference for some policy other than what the Zionists were urging. Yet in their definitive history of Truman’s decision-making (grudgingly acknowledged by Judis as “the most complete blow-by-blow account of what happened”), historians Allis and Ronald Radosh recorded the contradictory pressures on Truman from government officials sensitive to Arab wishes and a variety of individuals in and out of government favoring the Jewish cause. The president oscillated between the two camps and uttered words sympathetic to each along the way. In the end, he chose Israel, acted vigorously in its favor (not only casting America’s vote for partition in the UN, but rounding up other votes), and later forcefully defended what he had done. But Judis claims to know better. Truman, he writes, “would insist that he hadn’t bowed to pressure, but [this was] probably because he knew he had and was disgusted with himself.” Or else, “Truman preferred to suffer delusions rather than acknowledge the power that Israel and its supporters had over his decision making.”

In contrast to Zionists, Judis styles himself a Jew “as concerned about the rights of a Palestinian Arab as he is about the rights of an Israeli Jew.” This smug self-image lends a fillip to his animus against Israel. “I am… more upset and offended by Israel’s occupation of the West Bank than I am about China’s occupation of Tibet, although I think that on some objective scale of injustice, they are about equal,” he confides. This is offered as self-revelation, but it reveals more than he intends.

Tibet, a nation of a few million, with a distinct language, religion, culture, and ancient history, was invaded and conquered for reasons of pure rapacity by the largest nation on earth, under the rule of one of the most totalitarian regimes on earth. Israel, on the other hand, occupied the West Bank in the course of a defensive war against a much larger foe, and has repeatedly offered to evacuate more than 90 percent of it. All of these offers have been refused. Whether or not those offers have been sufficient, to judge these two cases as “objective[ly] equal” is to reveal a moral compass that is wildly askew. And to volunteer that one is more “upset” by the Israeli case is to confess a prejudice so deep as to disqualify one’s journalistic or historical work on the subject. This prejudiced and oddly self-centered approach to the problem is expressed in Judis’ proposed remedy. While declining to offer specific policy recommendations, he urges America to “redress that moral balance” of its past “tilt… toward Zionism and… Israel.” As he writes:

The Zionists who came to Palestine to establish a state trampled on the rights of the Arabs who already lived there. That wrong has never been adequately addressed, or redressed, and for there to be peace of any kind between the Israelis and the Arabs, it must be.

In other words, America should base its policies on “redress” of the past rather than consequences for the future. Such insouciance is breathtaking. Assuming, for the sake of argument, that Judis’ claim were true, should peace everywhere be made contingent on “redressing” the countless injustices of the past century? If so, woe unto us all. The accusation of injustice brings us back to the most important claim in Judis’ book, namely that the effect of Zionism was to “screw the Arabs out of a country.” The Arabs, however, got 16 other countries—by minimal count—and would have gotten 17 had they accepted partition of Palestine. Today, they hold enough sway in a handful of other countries of mixed nationality that the League of Arab States numbers 22 members. The Jews, far less numerous than the Arabs, sought one state for themselves in their ancestral homeland, a sliver of land amounting to one or two tenths of one percent of the vast Arab lands. Was it wrong for them to petition the sovereign powers and the League of Nations for this? And once the League, the determinative body under international law, had granted it, should it still be up for “redress”? And what of other states fashioned out of similar considerations, such as Lebanon, carved out as a home for Maronite Christians despite the presence of large Muslim populations? True, the Zionists did not really know how to deal with the Arabs of Palestine. They hoped to eclipse the local Arabs in numbers and/or to induce them to move, possibly by bribes. This may have been delusional, but it was not malevolent. Initial Arab objections to Zionism were primarily based on the conviction that it was obnoxious for Muslims to be ruled by non-Muslims; but this was hardly compelling, since they (like Judis) felt the reverse to be just fine. The Arab case grew stronger with the crystallization of national feelings among the Palestinian Arabs. The modern world honors nationalism, and supporters of Israel, the manifestation of Jewish nationalism, have little standing to dismiss the nationalism of others.

Chaim Weizmann, the first President of Israel, presents a Torah scroll to President Harry S Truman at the White House, May 25, 1948. Photo: Dennis Burlingham / flickr

But Judis is as confused (or deceitful) about the history of the Palestinian national movement as he is about Zionism. “In 1964,” he writes, “the Arab League designated the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), a coalition of existing guerrilla groups, the largest of which was Yasir Arafat’s Fatah movement, as the official representatives of the Palestinian people.” Not so. There were no existing “guerrilla” groups to speak of. Fatah, based in Kuwait and Syria, did not launch its first, essentially mythical “action” until 1965; and it initially spurned the PLO, which was created at the instance of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser as an instrument of pan-Arabism, not Palestinian nationalism. At the PLO’s helm, Nasser installed Lebanese-born Ahmed Shuqairy, the quintessential pan-Arab factotum who had served as assistant secretary-general of the Arab League; as well as a UN representative, sequentially, of Syria and Saudi Arabia. Shuqairy then composed the Palestinian National Covenant. “The most striking feature of [the] text,” writes Alain Gresh, former editor of Le Monde Diplomatique and an expert sympathetic to the Palestinians, “is the absence of all reference to any sovereignty either of the Palestinian people or of the PLO, or to a Palestinian state.” The humiliating defeat of Egypt and the other Arab states in 1967 discredited pan-Arabism and opened the way to the flowering of Palestinian nationalism. In the aftermath of the war, other guerrilla groups—the various “fronts for the liberation of Palestine”—began to be formed, and in 1968 Fatah for the first time entered the PLO and began to transform it into a fervently nationalist (and terrorist) movement. In the half century since, it has become a passionate cause, but it was virtually non-existent in 1917 when the Zionists, per Judis, were screwing people out of their country.

Just as weak as his historiography is Judis’s argument about the Zionist lobby. Truman’s capitulation to it, says Judis, established “a pattern… that would prevail for the rest of the century.” According to this year’s Gallup poll, 72 percent of Americans had an “overall” favorable view of Israel compared to 19 percent for the Palestinian Authority. The numbers have bounced around, but there has always been far more American support for the Israeli/Jewish side than for the Arabs. Lobby or no lobby, how often do elected officials fly in the face of such strong public opinion? And if they allow it to influence their decisions, is that craven or is it democracy?

The truth is that Judis’ derision of Truman as a self-deluded patsy comes from very different motivations than he claims. It reflects an enduring battle for the soul of liberalism with serious consequences for Israel. Truman was the apotheosis of a brand of liberalism that espoused the welfare of “the little guy” at home while standing strong against enemies abroad. For this, he was reviled by the radical Left, which rallied to the third-party candidacy of Henry Wallace, who blamed America for the Cold War. Judis is squarely within the Wallace tradition, a glimpse of which can still be seen in his passing reference to the 1948 split between Truman and Wallace Democrats as based on “Truman’s aggressive anti-Soviet policies.” Truman-style liberals would have said, with reason, that Stalin was the aggressive one. Ironically, it was as editor of The New Republic that Wallace began his crusade against Truman and liberal resistance to Stalinism. In that era, the magazine espoused a kind of Left-liberalism that tended to peg America as the villain. When Martin Peretz took over, he remade TNR in the Truman mold. Now, it is being repositioned once again, in an era when the Left has mostly trained its guns on the smaller quarry of Israel rather than on America. Should the magazine and, much more importantly, the broader liberal world turn from the tradition of Truman to that of Wallace—that is, should it absorb the attitudes of the radical left—Israel will surely get the short end.

![]()

Banner Photo: U.S. National Archives / Wikimedia