Just weeks before he died, one of Zionism’s early prophets was starting to get real traction in his plan to create a Jewish army in the heart of the Holocaust.

In June 1940—at the darkest military moment of World War II—three speeches were given in two days: one by a prime minister; another by a general; the third by a Zionist leader. Everyone knows the first; some have heard of the second; few are aware of the third. But the three are of a piece, and the third still resonates today, nearly 75 years later.

On June 18, Winston Churchill—who became prime minister only five weeks before—delivered a lengthy address to a subdued Parliament, dealing primarily with the catastrophic Dunkirk evacuation he had ordered. In May, Nazi Germany had overwhelmed the low countries of Western Europe in a massive new blitzkrieg; Hitler was days away from defeating France, and Britain was unprepared for the invasion it knew would be coming next. Today everyone remembers Churchill’s speech by its final sentence: “Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”

The same day, a little-known general, who had escaped the day before from France and would one day be heralded as the greatest French leader of the twentieth century, delivered a radio address in a London BBC studio. He called on French officers and men who were in Britain, or might be in the future, to get in touch with him, with or without their arms, to form a resistance. The next day he broadcast another call: “Faced by the bewilderment of my countrymen … by the fact that the institutions of my country are incapable, at the moment, of functioning, I, General de Gaulle, a French soldier and military leader, realize that I now speak for France.” In France, June 18 is now a national commemorative event, celebrated each year in memory of De Gaulle’s radio addresses.

On June 18, Vladimir Jabotinsky, head of the New Zionist Organization, was in New York City, preparing to deliver an address the next evening at the 4,500-seat Manhattan Center. He had spoken there in March to an overflow crowd of 5,000 people; now he held a press conference to preview the second address: he would call for a Jewish Army to fight “the giant rattlesnake.” On June 19 another overflow crowd showed up at the Manhattan Center, despite an extraordinary public effort by American Jewish leaders to thwart the event.

In June 1940, the Jews had neither a prime minister nor a general. Eight years before the creation of the State of Israel, they had two famous, formidable leaders in David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann, who would later become Israel’s first prime minister and president. But they also had a leader with military experience, whose Revisionist movement would go on to produce leaders like Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir—and whose eloquence compared to that of Churchill and De Gaulle. Jabotinsky’s June 19 speech is a forgotten piece of history, but it relates to the history we are living through now.

On September 1, 1939—one week after Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact—Hitler invaded Poland from the West. Two weeks after that, Stalin invaded from the East. By the end of September, Poland no longer existed as a separate country. It had been defeated, occupied, and formally partitioned by the two totalitarian powers.

More than three million Polish Jews—by far the largest concentration of Jews in Europe—were now suddenly under Nazi or Soviet control.

The scope of the disaster was apparent in the American Jewish Committee’s Annual Report, published after its January 1940 annual meeting. The report recounted that “well-known Nazi techniques … [were] applied with indescribable ferocity and ruthlessness in German-occupied Poland” to 1.5 million Polish Jews; and that “just as in the territories newly-acquired by Germany, the Nazi system is [being] quickly applied” by the Soviets to the other 1.5 million Polish Jews. The Soviets, the AJC reported, were imprisoning Jewish leaders, deporting rabbis to interior cities, banning Jewish teaching, and closing synagogues—“all part of the established Soviet pattern.” “Happily,” the AJC observed, “our country is not a party to this conflict.”

The catastrophe that arrived in 1939 had been visible on the horizon for years. In February 1937 the New York Times reported on the wave of anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe: “Anti-Semitism, raised by Adolf Hitler in Germany to the status of a political religion, is rapidly spreading throughout Eastern Europe and thereby turning the recurrent Jewish tragedy in that biggest Jewish center in the world into a first rate disaster of truly historic magnitude.”

The Times reported that five million Eastern European Jews faced “the prospect of either repeating the Exodus on a bigger scale than that chronicled in the bible … or spending the rest of their lives in an atmosphere of creeping hostility and dying a slow death from economic strangulation.” The wave of anti-Semitism, the Times reported, was at its peak in Poland.

Later that month, Jabotinsky testified in London before the Palestine Royal Commission (colloquially named the “Peel Commission” after its chairman, Lord Peel), which had been charged with making recommendations for Palestine. For years, Jabotinsky had been calling for a Jewish exodus from Eastern Europe, and the formation of a Jewish majority in Palestine as the basis of a Jewish state. He was savaged by other Jewish leaders for what they called his “evacuationism.” In his testimony before the Commission, Jabotinsky said:

I am very much afraid that what I am going to say will not be popular with many among my co-religionists, and I regret that, but the truth is the truth. We are facing an elemental calamity … We have got to save millions, many millions. I do not know whether it is a question of re-housing one-third of the Jewish race, half of the Jewish race, or a quarter of the Jewish race; I do not know; but it is a question of millions … [I]t is quite understandable that the Arabs of Palestine would also prefer Palestine to be the Arab State No. 4, No. 5, or No. 6—that I quite understand. But when the Arab claim is confronted with our Jewish demand to be saved, it is like the claims of appetite versus the claims of starvation.

In August 1938, Jabotinsky was in Warsaw, delivering an address on Tisha b’Av, the day set aside to remember the destruction of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. To the Jews of Poland, he set forth both a warning and a vision:

It is for three years that I have been calling on you, Jews of Poland, the glory of world Jewry, with an appeal. I have been ceaselessly warning you that the catastrophe is coming closer. My hair has turned white and I have aged in these years, because my heart is bleeding, for you, dear brothers and sisters, do not see the volcano which will soon begin to spurt out the fire of destruction. I see a terrifying sight. The time is short in which one can still be saved. I know: you do not see, because you are bothered and rushing about with everyday worries … Listen to my remarks at the twelfth hour. For God’s sake: may each one save his life while there is still time. And time is short.

I want to say one more thing to you on this day of the Ninth of Av: Those who will succeed to escape from the catastrophe will merit a moment of great Jewish joy — the rebirth and rise of a Jewish State. I do not know if I will earn that. My son, yes! I believe in this just as I am sure that tomorrow morning the sun will shine once again. I believe in this with total faith.

After the 1939 Nazi/Soviet invasion of Poland, the chance for a new Exodus was gone. Soon enough, the “first rate disaster of truly historic magnitude” the Times had described in 1937 would move well beyond economic strangulation.

On January 12, 1940, Chaim Weizmann, head of the World Zionist Organization, arrived in New York for a two-month visit. The New York Times reported his arrival on the society page: he came on the same boat as several other dignitaries, including J.P. Morgan’s sister Anne, the actress Ingrid Bergman, and a French hairdresser known as Antoine.

In his autobiography, Weizmann later recalled he found 1940 America in a “strange prewar mood … violently neutral.” He had learned of “hideous plans” that if Hitler overran Europe, “Zionism would lose all its meaning because no Jews would be left alive.” But in America he felt he “had to maintain silence [because] to speak of such things in public was [pro-war] ‘propaganda’!” He had to be “extremely careful” in his speeches, limiting his remarks largely to his hope for a Jewish homeland in Palestine once the war ended. He had a private meeting with President Roosevelt to sound him out about supporting increased immigration to Palestine after the war, but “the discussion remained theoretical.” On March 6, Weizmann returned to England, glad to leave behind the “uncomfortable” atmosphere in America.

The same day Weizmann left, the New York Times carried a report under the headline “Jabotinsky to Give Lecture.” It read: “Vladimir Jabotinsky, president of the New Zionist Organization of the World, will lecture on ‘The Fate of Jewry’ at Manhattan Center, 311 West Thirty-Fourth Street, on Tuesday, March 19, at 8:30 p.m., it was announced yesterday.”

Jabotinsky arrived in New York on March 13, 1940, on the Cunard Line’s 500-passenger Samaria, with 350 refugees from Nazi-controlled countries on board.

He had just published a 255-page book in London, entitled The Jewish War Front, arguing that World Jewry needed to form a Jewish Army to take an active part in the struggle against Nazism. The Jewish problem in Eastern Europe, he wrote, was of immense importance to world peace, and it was “a problem which means literally life or death to five or six million people.” He came to America not to enlist American Jews in a Jewish Army, but to try to persuade American public opinion to support such an army, which he wanted to form under British command from among the more than half a million stateless Jews in the world. As of 1940, there were about 432,000 Jewish refugees in various countries, and more than 210,000 Jews in Palestine.

Jabotinsky was confident he could build such a Jewish military force, because he had done it before.

In 1916, Jabotinsky—at the time only a young journalist, writer, and speaker—was the force behind the creation of the Jewish Legion, formed under the command of British Colonel John H. Patterson and comprising British, American, Canadian, and Palestinian Jews. The Legion fought alongside Allenby in 1917 to drive the Turks out of Palestine. At the time, most Jewish leaders thought Jews should remain neutral in the Great War, arguing that there were Jewish populations on both sides, and joining one side (Britain, France and Russia) might put at risk the Jewish populations in the other (Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, and Turkey). But Jabotinsky was convinced the Ottoman Empire would not survive the war, and that passivity and neutrality were enemies of the Zionist goal; the Jewish people could not expect to participate in the post-war division of the Ottoman Empire without participating in the war against it.

The Jewish Legion was the first organized Jewish military force in 1300 years (the prior one had fought with the Parthian armies to free Palestine from Byzantium in the year 614 C.E.). Col. Patterson later wrote a book, With the Judeans in the Palestine Campaign, effusively praising the Legion and Jabotinsky’s leadership and performance of it (Jabotinsky enlisted as a private, and was promoted to lieutenant). Jabotinsky’s own book, The Story of the Jewish Legion, was translated into English after World War II and included a foreword by Patterson comparing Jabotinsky with Churchill: both were “great writers and famous orators … both had the foresight and the prophetic power to foretell political events … both repeatedly warned their peoples—in vain—against the fatal policies of their mediocre leaders.”

Thus when World War II started—a war not only against Britain and France but against the Jewish people—the idea of forming a Jewish military force was not simply theoretical; it had been done two decades before, in a war in which the Jews were not then directly threatened.

On September 2, 1939, the day after the Nazi invasion of Poland, Col. Patterson received a call from Jabotinsky. They met in London that same afternoon to discuss a Jewish Army. Four days later, the London Times published a letter from Chaim Weizmann to Prime Minister Chamberlain, declaring the Jews would “stand by Great Britain and will fight on the side of the democracies.” The letter offered Jewish manpower, technical ability, and resources. But nothing came of the offer.

The overflow turnout at the Manhattan Center on March 19, 1940 was no doubt assisted by the New York Times coverage of Jabotinsky’s arrival in America. The Times noted he had “commanded the Jewish Legion in Palestine during the World War” and had conferred with British leaders about Jewish participation in the new war. He told the Times that if the new war (which was then in its “phony war” stage) escalated into a real one, “there is going to be a Jewish army, fighting under a Jewish flag on the side of the democracies.”

At the Manhattan Center, Jabotinsky told the crowd that whether the “quasi-war” in Europe would become “a real war and spread” or “fizzle out in a precarious peace,” there was going to be “a worldwide revision of all international and national conditions”:

Should the democracies lose the war, their eclipse—especially that of France, which is Europe’s main window to fresh air—will enthrone medievalism right up to the Atlantic shore. But even an allied victory, if the present policy with regard to Jews is to continue, threatens to leave those Jews in the lurch. That policy now consists in keeping the Jews off the war-map. When the war broke out we hoped to be recognized and treated as one of the allied peoples, offered Jewish troops and other important forms of collaboration. All that was rejected: the Jewish ally is not wanted. His problems are rigorously excluded from the list of war aims.

The old fallacy, the curse of our past, has been revived: that there is no Jewish problem; that all our troubles can be cured en passant by general measures of progress, and there is no need to worry about any special remedies. The allied victory will ensure democracy and equality … and that will be enough for the Jews.

The next day, the New York Times reported on Jabotinsky’s speech:

More than 5,000 persons jammed the Manhattan Center to hear the man who headed the Jewish Legion in Palestine in the World War, in a two-hour statement of his party’s case. …

None of the leaders of the Zionist Organization of America, which differs with the Jabotinsky point of view in many ways, was observed in the audience …

The most remarkable fact in the Times report was not the 5,000-person turnout—although such a turnout in isolationist America was remarkable enough—but the fact that the ZOA leaders had been conspicuously absent. What made them unwilling to attend a huge outpouring of Jews, at the Manhattan Center, a few blocks from their offices? The brief answer is that American Jewish leaders considered Jabotinsky “right wing,” while they were liberals allied with Roosevelt and his party; they considered him a “militarist,” which they thought inconsistent with Jewish values; they considered him an “extremist” in matters they thought needed quiet diplomacy, given America’s neutrality; and they wanted to avoid having Jews perceived as an ethnic group pushing a pro-war agenda.

After Jabotinsky’s Manhattan Center speech, a prominent Zionist leader wrote his colleagues that Jabotinsky was “making an impression on American Jews” and that it was necessary to “destroy [his] influence … on the American public.” The Zionist organizations combined to print a 36-page pamphlet warning Jews against the “seductiveness” of Jabotinsky’s rhetoric, “particularly when supported by [his] powerful personality.” They castigated his “notorious” 1937 “Evacuation Scheme,” accusing him of “abetting the anti-Semitic desire to treat Jews as aliens and drive them out of their lands of residence” in Europe.

Benzion Netanyahu, Jabotinsky’s executive assistant (and father of the current prime minister of Israel), booked the Manhattan Center again, this time for June 19, and Jabotinsky was determined to make the event a broad show of support for a Jewish army. He sent a representative to meet in Washington with Lord Lothian, the British ambassador. Three days later he sent Col. Patterson to meet Lothian. Then Jabotinsky and Lothian themselves met for lunch in New York. The week before the rally, the British embassy informed Jabotinsky that the British consul general in New York would attend.

The American Zionist organizations learned of Lothian’s decision and mobilized to reverse it. Two days before the rally, they sent a delegation to Washington to meet Lothian, led by Rabbi Stephen S. Wise. After the meeting, a curt statement was issued to the media: “American Zionist organizations are not associated with Mr. V. Jabotinsky’s activities in any way.” Lothian thereafter withdrew the British consul general from the rally.

The June 19 rally proceeded at an extremely perilous moment in history. That morning’s New York Times reported on the “complete military and political collapse” of France. The prior day’s German war communiqué reported that “[y]esterday alone far more than 100,000 prisoners were taken,” with “booty” comprising “the complete equipment of numerous French divisions.” The Times headline was “Munich is Gay as Dictators Meet,” accompanied by pictures of Hitler and Mussolini before a cheering crowd. The article reported “all Munich [is] riding on the crest of an exhilarating wave,” bathed in the “bright sunlight of the thought that this war may now be almost ended.”

That night, another capacity crowd came to the Manhattan Center, with people lining the walls. The day before, Churchill had made his “finest hour” address, which the Times described as given in a “tired voice … deadened with grief for the France he loved,” an attempt by him “to awaken his somnolent, complacent countrymen to the reality of the danger facing this island and at the same time convince them that theirs was not a hopeless struggle.”

Jabotinsky took the stage at the Manhattan Center and urged the audience not to “forecast historical events on the basis of last week’s headlines”:

[I]f there will be an invasion [of Britain] it will not be millions of men nor thousands of heavy tanks. The figures are bound to be on a much smaller scale. And that means that foreign help, to be effective, need not wait till millions of soldiers can be sent over. Every division now may prove decisive … [which] has a direct bearing also on the prospects of a Jewish Army …

[T]here is still time ahead of us for changes to come in; there are still immense probabilities for quite decisive changes. One need not name them: enough to say that God’s box of tricks is by far not emptied yet. This is why my belief in the ultimate defeat of the rattlesnake is not shattered—provided we all remember the principle by which all great nations live and without which they die, the principle which is the secret of our own Jewish people’s survival through all these centuries of torture: No Surrender.

What was needed, Jabotinsky declared, was a Jewish Army to “signify that the Jewish people chooses a cloudy day to renew its demand for recognition as a belligerent on the side of a good cause.” With Col. Patterson on stage with him, Jabotinsky said he wanted to see the “giant rattlesnake” not simply destroyed, but “destroyed with our help.”

There is stuff for well over 100,000 Jewish soldiers even without counting American Jews … [H]ad our request for a Jewish Army been granted early in the war when we first submitted it to the Allies, that source alone would have yielded three to four divisions. Even now it can yield two at least. …

There were periods—there still are, there still will be in the months before us—when the impression is that England’s plight leaves America only superficially rippled, while the basic attitude of this mighty nation is expressed in the words, “The Yanks are not coming.” As an observer and a reporter, I contest this impression … [I would say:] “Mr. Churchill, they are coming!” But “they” will be delayed. It takes long to equip a battleship; smaller craft can be delivered quicker. I want the Jews “coming” at once.

The New York Times reported the speech in a story quoting both Jabotinsky (“I challenge the Jews, wherever they are still free, to demand the right of fighting the giant rattlesnake … as a Jewish Army”) and Patterson (“If I were a Jew, nothing would give me greater pleasure than to show the German criminals that the Jews of today are capable of fighting just as their forefathers were when … they shook the mighty Roman Empire”).

The speeches struck a nerve, invigorating people frustrated by the failure of American Jewish leaders to respond effectively to the catastrophe facing European Jews. Offers to serve in the prospective Jewish Army poured in; the Canadian foreign ministry offered training camps; Jabotinsky’s New Zionist Organization moved to raise funds and conduct grassroots efforts across the country.

On June 21, Jabotinsky wrote to Lord Lothian, telling him the Manhattan Center event had demonstrated the Jewish Army proposal had “caught on with the imagination of Jews and non-Jews, which after all is the main element of final success.” He acknowledged there would be practical difficulties before a decision on a Jewish Army could be made, mentioning one in particular:

I understand from the press that some of the difficulties arise from a faint-heartedness of a routine-bound Jewish leadership rather than from the British Government. Just as in 1916.

At the end of July, Jabotinsky decided to return to England the following month, hoping to reunite with his wife (who had been unable to get a visa to join him in America) and to resume negotiations with the British government for a Jewish Army under British command. On August 2, Jabotinsky signed a contract to publish a book on the Jewish problems that would follow the war.

On August 3, the Times reported in a front-page article that Gen. De Gaulle had been stripped of his rank by the French collaborationist government and condemned to death for his June BBC radio addresses. Another story reported that 20,000 Canadian troops arrived in Britain—in a division that included several hundred American volunteers from five states.

Late that evening, Jabotinsky traveled upstate to visit the New York camp of his Betar youth organization, which before September 1, 1939 had 78,000 members worldwide (half in Poland, where the head was a 25-year old Jew named Menachem Begin). Betar’s slogan (“Hadar”) meant Jewish honor, reflected in the Betar hymn Jabotinsky had composed: “Whether you be a beggar or a hobo/ You were born a son of kings/ Crowned with the crown of David … Never forget your crown.”

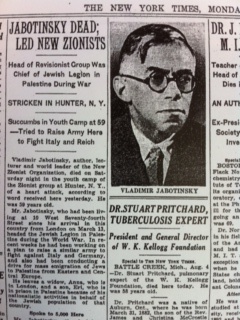

Monday, August 5 was a hot day in New York. As readers of the New York Times paged through the newspaper that morning and came to page 13, they found a picture and a story extending the entire length of the paper that, at least for Jewish readers, generated profound shock:

Vladimir Jabotinsky, author, lecturer and world leader of the New Zionist Organization, died on Saturday night in the youth camp of the Zionist group at Hunter, N.Y., of a heart attack, according to word received here yesterday. He was 59 years old.

Mr. Jabotinsky … headed the Jewish Legion in Palestine during the World War. In recent weeks he had been working on a plan to raise a similar army to fight against Italy and Germany, and also had been conducting a drive for mass emigration of Jews to Palestine from Eastern and Central Europe. … Mr. Jabotinsky stirred intense loyalty among his followers and deep bitterness among his opponents in the Zionist movement. …

Jabotinsky had the multiple appeal of poet, soldier, orator, and personal fire and magnetism. … [I]mbued as he was with the ideal of a self-defending Jewish State in Palestine, and with a nature preferring forthrightness to compromise, it was natural that he should be constantly in the center of controversy.”

The funeral was held the next day at the Gramercy Park Chapel on Second Avenue, with 750 in attendance, including prominent Jewish leaders and representatives of the British, Polish and Czech consulates. Three rabbis officiated; 200 cantors chanted; 12,000 people stood outside in the street. In accordance with Jabotinsky’s wishes, the services followed the precedent of Herzl’s 1904 funeral: no speeches, eulogies, or instrumental music.

The Times reported that the coffin, draped with a Zionist flag, was carried out by an honor guard of 50 Betar members. “Many men and women wept, as Martin Winnick, national bugler of the Jewish War Veterans, sounded taps”:

Estimated by Inspector John DeMartino, who directed fifty patrolmen and five sergeants, as one of the largest funerals on the East Side, a throng of 25,000 followed the cortege or lined the route. All vehicular traffic was stopped on Second Avenue as the hearse and guard of honor went north on Second Avenue to Fourteenth Street, east to First Avenue, south to Thirteenth and then west again to Second Avenue.

Proceeding south on Second Avenue, where Jewish theatres and homes had hung out mourning drapes, the cortege stopped between Tenth and Ninth Streets in front of the funeral chapel, where the cantors sang a Jewish mourning song and the Jewish national anthem.

At Houston Street and Second Avenue, a salute of honor was given the hearse, and then a motorcade of fifty cars and eight buses left for the New Montefiore Cemetery at Farmingdale, L.I. where a military service was held. Burial was in the cemetery’s Nordau Circle.

The next day, August 7, the Jewish Agency held memorial services for Jabotinsky in London, where Chaim Weizmann gave the principal eulogy, recounting his relationship with Jabotinsky going back to the efforts to form the Jewish Legion in 1916. He said Jabotinsky had been motivated by “one great idea, to bring about a solution of the Jewish problem as quickly as possible”:

History will judge whether Jabotinsky or the [World] Zionist Organization was right … Jabotinsky was burned up by a sacred fire. In his opinion we had only a limited time in which our program could be realized. This may and may not be so. Factors and events independent of the desires of the Jewish people forced us to follow a path which may be difficult and above all slow.

Weizmann implicitly rejected Jabotinsky’s “opinion” that “we had only a limited time,” and he implied history would eventually judge Jabotinsky wrong about the speed necessary to solve the Jewish problem—or that history would at least criticize Jabotinsky for not adequately appreciating the process would be difficult and “above all slow.”

For 80 percent of the 7.7 million Jews then living in Eastern Europe, however, there would be no benefit in the succeeding years from a Zionism resigned to following a path “above all slow.” Like Jabotinsky, those six million Jews would not live to see a Jewish state.

In 1956, Louis Lipsky, the American Zionist leader who in 1940 had urged his colleagues to combat Jabotinsky’s influence (and who had joined Stephen S. Wise’s delegation to meet with Lord Lothian to undercut the June 19 address), published an admiring remembrance of Jabotinsky. Two sentences from it can provide the epitaph for this story.

Lipsky wrote about Jabotinsky that “while we Zionists saw the clock at six, he saw it at twelve. He did not know what was meant by premature; whatever was true was timely.”

Lipsky’s remembrance was an implicit acknowledgment that the response of the American Jewish establishment to the leader who came to America in 1940 to speak for Eastern European Jewry, and who sought to build support for a Jewish military resistance, would not be remembered as the establishment’s finest hour.

![]()

Banner Photo: tamoryair / Wikimedia