Iraq is home to the Cradle of Civilization, where two mighty rivers helped create life as we know it. So what will happen now that Iraq’s water is drying up? And what can the country do to turn the tide?

For years, a host of analysts, pundits, and politicians have advocated the breakup of Iraq, and their calls have only grown louder since the Islamic State’s 2014 waltz through a solid third of the country. Some support independence for the Kurds in the north, Sunni Arabs in the west, and Shiite Arabs in the south. Others call for federalization, but foresee so much autonomy for the three regions that it differs from partition in name only. All hope that separation can lead to peace between the three communities. But these hopes are belied by the physical reality of Iraq, and especially its water.

Water does not know borders. It does not flow in neat lines or handily apportion itself into thirds. Yet water access is one of the most critical factors shaping Iraq today, and as existing shortages worsen to crisis levels, it has become clearer than ever that Iraq, and all its people, need a federal state powerful enough to manage the area’s remaining water resources.

Iraq is the land of the Tigris and Euphrates, the twin rivers that nourished the beginnings of human civilization. It was on their banks that agriculture, cities, and writing originated. The rivers so dominated the landscape that they lent the region its Greek name, Mesopotamia, “the land between the rivers,” and nourished lush landscapes that inspired the myths like the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and possibly even the Garden of Eden itself.

But those days are over. Due to waste, mismanagement, and unconscionable diplomatic missteps (both international and inter-ethnic), Iraq’s water situation has become dire. Only half of the demand for water in Iraq is being met, and the amount of water available per capita has declined over the last half century by a whopping 75 percent. “We have a real thirst in Iraq,” Iraqi Minister of Planning Ali Baban told The New York Times in 2009. “Our agriculture is going to die, our cities are going to wilt, and no state can keep quiet in such a situation.”

A water tanker gets filled up in an-Nasariyah, Iraq. Photo: SSGT Quinton T. Burris / U.S. Air Force / Wikimedia

He wasn’t being hyperbolic: The last few decades have seen half a million acres of arable land, equivalent to the size of Rhode Island, abandoned for lack of water. Some specialists fear that if nothing is done, within a decade or two, the Tigris and Euphrates won’t even make it to the sea.

These problems cannot be fixed by dividing Iraq. On the contrary, such an action would make the crisis worse at all levels. “If the country was split there would definitely be a war over water,” Michael Stephen, an analyst for a Qatari think tank, told The Guardian in 2014. This prediction has become even more credible as a result of the Islamic State’s use of water as a weapon of war since 2014. Only a powerful federal government will be able to coordinate a water policy that fits the region’s geography, transcends ethnic rivalries, and leverages Iraq’s strategic and natural resources to produce a sustainable solution. The people of Iraq will be held together by water, whether they like it or not.

Iraq’s transformation from one of the only water-rich nations in the Middle East to a land of drought began about half a century ago. During the 1960s, the country was a net food exporter, and enjoyed about 12,000 cubic meters of renewable fresh water per person annually, which is, perhaps surprisingly, 20 percent higher than the United States enjoys today. But Iraq, where most of the country gets less rainfall than Arizona, was extremely reliant on the Tigris and Euphrates, and both rivers have a crucial drawback: their headwaters are almost entirely outside the country. Not a single tributary, brook, or stream feeds into the Euphrates within Iraq’s borders. Instead, the water comes as runoff from the Pontic and Taurus mountain ranges in eastern Turkey.

As advanced dam-building techniques proliferated around the world (aided by the United States and Soviet Union, exporting their technological prowess to their respective client states during the Cold War), Turkey and Syria began building a series of dams and diversions on the rivers that feed the Tigris and Euphrates. The effect on Iraq has been dramatic. Over the last half-century, the flow of water to the Tigris has decreased by around 50 percent. In the case of the Euphrates, the effect was even greater, as water flow fell by 90 percent. At the same time, Iraq’s population quadrupled.

The single biggest culprit is Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Project, known by its Turkish acronym GAP. A mega-project decades in the making, it consists of 22 major dams on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and their tributaries, and makes the Tennessee Valley Authority look like child’s play. The project provides water and electricity to eastern Anatolia and parts of the more heavily populated west, and is seen by the Turkish government as key to developing and integrating majority-Kurdish areas of the country. The hope in Ankara is that economic growth and a visible, peaceful footprint for the Turkish state will win ethnic Kurds over and undermine the long-running insurgency of the separatist Kurdish PKK. Meanwhile, Iraq and Syria are both mired in civil wars, rendering opposition to GAP virtually meaningless.

Yet even if Iraq received more water from Turkey, it would still be plagued by shortages. The agricultural sector, which accounts for nine-tenths of Iraq’s water use, relies on long-outdated methods. Most farmers transfer water in irrigation ditches or underground tunnels called karez that have been in use for thousands of years, and much of the water is lost to evaporation or runoff.

The adoption of modern, if more expensive, techniques would revolutionize Iraq’s water situation. Israeli-pioneered drip irrigation can equal the yield of traditional flood irrigation while using less than a third of the water, and the best systems can cut water usage even more dramatically.

But the karez is not so easily replaced, in part because it is more than just a method of transferring water. It brings communities together. One Kurdish farmer named Ali described the village karez to Al-Jazeera: “Farmers would use the water. On hot days, children would play in the water. In the evenings, people would gather at the karez to talk about village things.” When his village’s karez dried up, it was devastating. “The karez was the source of life. The village now feels like a family that has lost its father.” Modernizing Iraqi agriculture would mean moving away from such wasteful open-water systems, but would also greatly affect local culture. Poor farmers with few resources and an inherited way of life are not likely to make big changes on their own.

That’s where the government needs to step in. “We must start using modern irrigation technology as we are still using the old, traditional ways which waste huge amounts of water,” Abdul-Razzaq Hassoun, head of the Planning Ministry’s Agricultural Statistics Department, said in 2012. But since then, little has been done. Instead, the government has continued to effectively favor the country’s main cities over the rural areas where the biggest improvements could be made. While safe water is available to almost all residents of Iraq’s urban areas, only 56 percent of people in rural areas have access to safe, regular drinking water, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Corruption, a reliance on oil profits, and inefficient conservation practices have contributed to Iraq’s water scarcity.

Rural farmers see themselves as having been consistently overlooked, and they’re not wrong. Iraq’s oil wealth has caused the country to fall victim to what some economists call the “resource curse.” The country’s oil industry hogged talent, attention, and investment, while raising the value of the Iraqi dinar, which made it cheaper to import food. Oil wealth also subsidized farmers through various social welfare measures, reducing the incentive to stay competitive. The result was that agriculture stayed at a standstill even as Iraq as a nation moved into middle-income status. Inefficient irrigation methods continued to be used even as the water flow from Turkey was reduced and the Iraqi population ballooned.

Now, with crops failing and once-fertile land being abandoned, farmers are becoming refugees from their villages, and are eager for help from any source. When the Iraqi government fails them, some turn to groups like the Islamic State.

Drastic decreases in water resources have already been linked to regional conflict. One of the areas hit hardest is Iraq’s upper farming region of the Euphrates Basin, including cities like Haditha, Hit, Ramadi, and Fallujah. Sound familiar? That’s because the same region has been the epicenter of the revival of the Islamic State. Across the border in Syria, the situation is much the same; water shortages have even been cited by some scholars as a significant contributing factor of the original Syrian revolt in 2011.

Conflict over water is sure to spike dramatically if Iraq is split up or the regions are given local control over water control sites; such an eventuality would take an infrastructure system designed with the whole nation in mind and fracture it, leaving feuding ethnoreligious groups with odd bits and pieces and increasing the leverage some groups have over others. “The control of water barrages and hydroelectric works have always been of great geostrategic importance in Iraq,” a researcher at Queen Mary University of London told Business Insider.

The Shia south of the country, where the largest portion of the population lives, is extremely reliant on water from the Tigris and Euphrates, which flow through Sunni Arab and Kurdish areas. A number of dams, especially those at Mosul, Samarra, Ramadi, and Fallujah would give the Kurdish and Sunni areas the ability to block water flows to the Shiite population. There would certainly be popular pressure from the inhabitants of dam-controlling regions for governments to hold back more water for local use and let less flow downstream, and resentment from downstream Shiite areas would result. Indeed, one of the first moves the Islamic State made after capturing Ramadi in 2015 was reducing flow on the Euphrates, causing ecological damage and widespread drought downstream.

The numbers showing Iraq’s thirsty future come from one of the foremost authorities on water use in Iraq, Prof. Nadhir al-Ansari, lately of the Luleå University of Technology in Sweden. He recognizes that the difficulties are as much political as they are ecological. “It is the politics that make it complicated,” he told Francesca de Chatel, author of Water Sheikhs and Dam Builders: Stories of People and Water in the Middle East. “Mix politics and public relations with hydrology and science, and I guarantee you won’t get good results.”

But fixing the situation will indeed require mixing politics and hydrology. Upgrading Iraq’s water infrastructure and instituting rationing policies as the water shortage worsens means coordinating action all across the country. Dam construction and improvements will ultimately help the whole country, but in the short term they will send funding generated by oil in the Shiite south to repair infrastructure in the north, creating jobs there. It takes a long-term, nationally-level focus to understand that nobody will benefit in the long run from each major ethno-cultural group acting in their short term self-interest.

A striking example of inter-ethnic funding and administrative disputes imperiling the country’s water infrastructure is that of the Mosul Dam. The dam was foolishly built by Saddam Hussein’s regime on a shaky foundation of gypsum, and requires constant upkeep to prevent collapse, which would send a deadly wave of water downstream towards cities like Mosul and Baghdad, where millions live. The Islamic State temporarily seized the dam in 2014, ruining some of the equipment, and after maintenance workers returned when the area was liberated, budget disputes cut off funds to the effort to save the dam. The central government in Baghdad cut off salaries to government workers in the Kurdish Regional Government, where the dam is located, so most workers left. As the months went by, the Iraqi government remained mired in regional squabbles while the dam came closer and closer to collapse.

Eventually, after international alarm raised by engineers about the danger of collapse, funding was restored. But it was a close call the underscores the necessity for cooperation throughout the river systems that make up most of Iraq.

But perhaps the biggest factor in remedying Iraq’s water crisis is fixing its relationship with Turkey. Iraq is a downriver state, a situation that always poses challenges. Yet there are other such states (Egypt being a prime example), and none of them are facing water difficulties on the scale of Iraq. Part of the reason that Iraq has been hit so hard-hit by upstream developments is that Turkey is simply bigger and stronger. But Iraq can still find leverage if its regions act in concert, instead of against each other.

Securing an equitable water-sharing agreement with Turkey is never going to be easy for Iraq. Turkey is inherently favored by being the upstream nation, but is also wealthier, more populous, and better connected internationally than Iraq. It is hard to imagine anyone, even Saddam Hussein, credibly threatening a key NATO member like Turkey.

But it’s not as if Iraq were a pushover. On the contrary, in the mid-20th century, Iraq was an oil-rich regional powerhouse and a top buyer of up-to-date Soviet weaponry. That it failed to negotiate well with Turkey is due in large part to Saddam Hussein’s criminal mismanagement of Iraq’s strategic position. Over the course of his rule, he continually occupied himself with quixotic and disastrous attempts to seize more oil-producing territory from Iraq’s neighbors. His attempts to annex Iran’s Arab-majority Khuzestan province in 1980 and the entire nation of Kuwait in 1990 led to bruising defeats. Iraq’s oil output fell, its infrastructure was severely damaged, and its military was degraded. Sanctions triggered by Hussein’s genocidal campaigns against Kurds and Shiites crippled Iraq until the 2003 toppling of his regime. Since then, Iraq has had too many pressing, immediate security issues to focus on long-term threats like water shortages. All the while, Turkey has been working on one of the biggest water-control projects in world history.

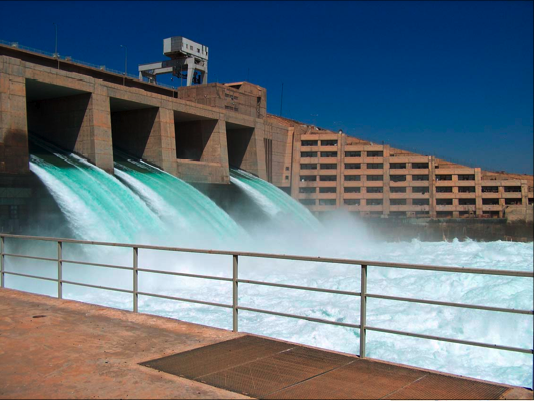

The Haditha Dam is the second-largest contributor to hydroelectric power in Iraq. Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers / Wikimedia

Yet, there’s no reason Iraq should remain powerless in negotiations with Turkey. According to statistics from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, Turkey imported 27 percent of its oil from Iraq in 2014, and that number could rise in the future. Turkey could also come to see Iraq’s stability as important for its own security. Recent months have seen dozens of terror attacks on Turkish targets launched by ISIS or PKK-linked groups, both of which maintain bases in Iraq. The PKK—which has been waging a low-intensity war against Turkey for years—has an extensive footprint in the Qandil Mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan that the Turkish government believes fundamentally threatens the integrity of Turkey. Promising to clamp down on these guerilla bases could be a bargaining chip in exchange for a water-sharing agreement.

Neither oil nor security will work as negotiating assets, however, if Iraq breaks up. If it splits into three states, the Sunni and Shia Arab states would not have the ability to deny the PKK territory in the hills, which are in areas currently under the de facto control of the Kurdish Regional Government. If the Shia state, which would have by far the most oil wealth if Iraq split along current ethnic lines, were to negotiate with Turkey to exchange oil for water, both oil and water would need to flow through either a Sunni Arab or Kurdish state in between.

The idea that water control issues lead to strong centralized states is not a new one. Karl Wittfogel, a German-American historian, once proposed that the presence of easily controllable water sources—major rivers, as opposed to streams and rain—led directly to “hydraulic empires” that favored despotic rule. While later historians have criticized Wittfogel’s reading of Chinese and Mesopotamian history, and questioned the notion that riverine societies are more likely to be ruled despotically, the basic notion still rings true: Societies dependent on rivers require more centralization and bureaucratization to support the construction of dams, dikes, and canals.

Without a powerful federal government to coordinate infrastructure development, balance regional interests, and negotiate for the whole country’s betterment, Iraq stands little chance of dealing effectively with its water crisis. Instead, if the country is allowed to fracture further, the crisis will get worse and fuel more hatred and violence. It has already been made clear by the conflicts of the last two and a half decades that getting Iraq’s major ethno-religious groups to cooperate is not and will never be easy. But the logic of the river basins’ geography is clear: either move people’s hearts, or move the rivers, dams, and mountains that define the region’s hydrology. The former may be difficult, but the latter is impossible. And when Iraq’s thirst is quenched, some of the hate that has defined its history will be quenched, too.

![]()

Banner Photo: Spc. Charles Gill / flickr