A murdered prosecutor, a dismissed indictment, collusion with Iran, and leaks of anti-Semitism at the highest levels—this is Argentina today.

Alberto Nisman, Special Prosecutor in the case of the 1994 truck-bombing of the AMIA Jewish community center in Buenos Aires, was found dead in his apartment at some point late in the evening of Sunday, January 18, 2015, with a single gunshot wound in his head. That’s all we are ever likely to know with certainty.

Was it suicide? Perhaps. But why have repeated scans found no gunshot residue on Nisman’s hand? Why did he shoot himself with his right hand when he appears to have been left-handed? How come all those who knew him well, including his ex-wife, dismiss the idea of suicide out of hand? By burying him alongside the 85 victims of the AMIA massacre in the Jewish cemetery at La Tablada, the Jewish community of Buenos Aires has made a clear statement that it does not believe Nisman killed himself.

If Nisman was murdered, who did it and why? It seems certain that the answer to both questions is connected to the AMIA case. Nisman had been in charge of the investigation since 2004, and in 2006 he issued arrest warrants for a number of senior Iranian officials he suspected of planning the attack. A few days before his death, he made a formal criminal complaint against Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and Foreign Minister Héctor Timerman, among others. He accused them of illegally negotiating with the Iranian government in order to exculpate the accused in return for improved commercial relations and, more specifically, an oil-for-grain deal. Nisman’s body was found one day before he was scheduled to address a congressional committee about his allegations. The substance of his complaint has since been ratified by another prosecutor and passed on to Federal Judge Daniel Rafecas, who on February 26 dismissed it on the grounds that there was no evidence of a crime having taken place. It remains to be seen whether Gerardo Pollicita, the prosecutor who replaced Nisman for this case, will appeal the decision.

The question of “why” immediately leads us to the question of “who.” Was it the Iranians? Was it the Argentine government, seeking to silence a threat to its president? Did some faction of Argentina’s myriad intelligence services—both legal and illegal—kill him in order to dump his body at the feet of the government and provoke a political crisis?

The contemporary history of Argentina is replete with unresolved high-profile homicides and doubtful suicides, which strongly suggests that we will never know for sure how Nisman died. The outcome of the official investigation is almost certain: It will drag on for some time. Enough evidence to fill a cathedral will be collected. Stained from the start by government meddling, as well as freewheeling speculation and finger-pointing from the president, there will be little faith in whatever verdict is eventually reached.

Nonetheless, a consideration of the tortuous history of the AMIA case and how it has been managed by the Argentine government, especially since 2004, may allow us to achieve some understanding of the forces within Argentine politics and society that converged around the person of Alberto Nisman and likely cost him his life. It may also tell us something about the worth—or lack thereof—of Jewish lives in Argentina.

The AMIA bombing was one of the worst terrorist atrocities committed against Jews since World War II, and it remains essentially unsolved. None of the primary suspects have ever been so much as arrested, and cases against local secondary participants have come to nothing.

The reasons why have everything to do with the murky world of Argentine politics. At the time of the bombing, Carlos Menem was president of Argentina. The following year, he would go on to be comfortably reelected to a second four-year term. Menem was the most prominent advocate of neoliberalism in South America and a staunch ally of the United States. He ended hyper-inflation, fixed the Argentine peso at par with the U.S. dollar, privatized a wide range of state-owned businesses and utilities, and unashamedly molded Argentine foreign policy to suit the requirements of the U.S. He also proved to be as hopeless as his successors when it came to the catastrophe of the AMIA investigation.

It is important to remember this today. The path that led to Nisman’s death did not begin with the current president and it won’t end when she is gone. It began when the trail was still fresh and Argentina’s leader was the toast of Washington, regarded by many in Western capitals as a model for other countries in the region. Perhaps more surprisingly, the Menem government’s inability to arrest, never mind convict, anyone in connection with the bombing of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires in 1992, which left 29 dead and hundreds injured, did not damage his international cachet either. Dozens of murdered Jews and non-Jews produced not the slightest inconvenience for Menem while he was in office, either at home nor abroad. If Nisman was indeed murdered, this fact could not have escaped the notice of those responsible.

Marchers protest Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and the death of Alberto Nisman. Photo: jmalievi / flickr

To say that the initial investigation into the AMIA massacre was disastrous is an understatement. It now seems certain that the inquiry, led by Judge Juan José Galeano, was carried out with the specific intention of convicting a handful of low-level accessories while leaving the main suspects in peace. Every conceivable error and abuse was committed during the investigation, including the bribing of a witness and the loss of vital phone tap recordings. No one really knows why this occurred, but there are plenty of theories. The more popular ones refer to massive bribes and the claim that Syria, where Menem’s family originated, had some involvement in the attack, prompting the president to protect the country of his ancestors. Whatever the truth might be, the lack of international consequences for his government’s failure to solve the Israeli embassy bombing case must have encouraged Menem to think that there would be no serious repercussions for his administration if this fresh atrocity was left unsolved. He was proved right.

Nonetheless, a group of corrupt police officers and a dealer in stolen cars were eventually tried on charges of having played a secondary role in the attack. In 2004, they were all acquitted. A subsequent Supreme Court decision overturned the acquittal of one of them—a stolen-car dealer named Carlos Telleldín—and ordered a second trial. Thus far, no date has been set for it.

The same ruling held that the initial investigation into the attack, in spite of its flaws, had produced a considerable amount of valid evidence that the AMIA building had indeed been destroyed by a truck bomb. This, at least, put paid—from the standpoint of the law if not that of many Argentines and quite a few prominent opinion-makers—to various rumors and conspiracy theories about the case. These included the claim that the fatal explosion had been caused by an arms dump maintained by members of the Jewish community.

The process ultimately ended with Judge Galeano’s impeachment. He, as well as former President Menem and a number of others, will stand trial later this year on charges of having deliberately concealed the identities of the major perpetrators of the attack.

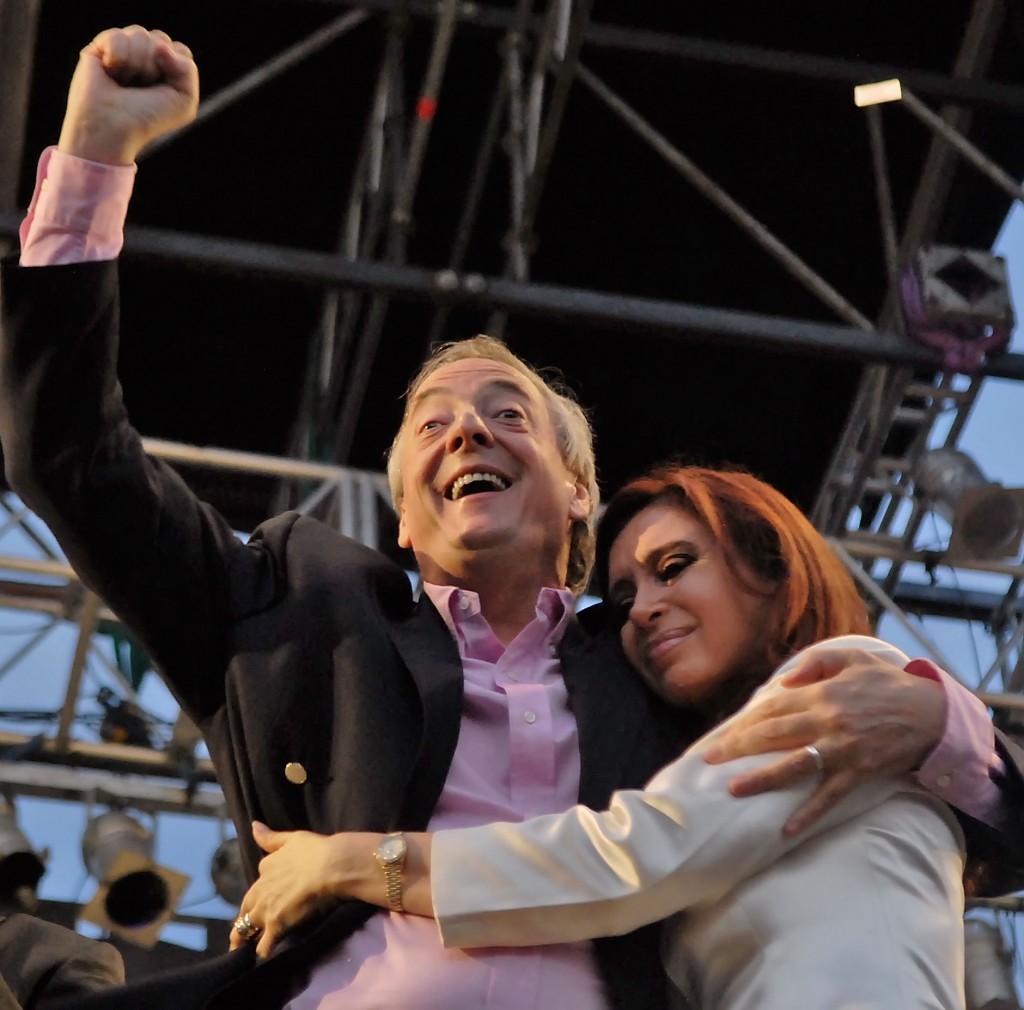

Néstor and Cristina Kirchner at an election-eve campaign rally, 2007. Photo: Presidencia de la Nación Argentina / Wikimedia

Alberto Nisman first became involved with the AMIA massacre investigation early on, when he worked as an auxiliary prosecutor on the team led by prosecutors Eamon Mullen and Ricardo Barbaccia, both of whom are currently awaiting trial for bribing Telleldín into giving evidence that implicated members of the police force in the bombing. It seems likely that during this period Nisman began to develop contacts with local and foreign intelligence services, which later brought him to the attention of Menem’s successor (and the current president’s late husband), Néstor Kirchner, at a time when Kirchner was searching for a suitable candidate to revive the investigation and restore its credibility.

Argentina’s security and intelligence services have an inglorious history of anti-Semitic attitudes and anti-Semitic violence. It must have taken considerable skill for a young and ambitious Jewish lawyer like Nisman to win their confidence. But, while it is impossible to say for sure, some of the contacts Nisman made during this period may well have played a role in his death.

In May 2003, Néstor Kirchner became President of Argentina. He came to power just as the country was beginning to recover from a social and political crisis caused by the collapse of the Argentine peso in 2002. The economy had already begun to grow again, but there was still a sense that Argentina was teetering on the edge of the abyss. Kirchner needed to build a political base in order to counteract this sense of instability and ensure that he wouldn’t be forced out of office early, as his predecessor had been. He found the cause he was looking for in a sudden commitment to human rights, at least as he understood that term, and to healing some of the wounds left by Menem’s tenure—the still-unsolved AMIA case among them.

Under Kirchner, there was a marked and immediate improvement in the quality of lip service paid to the importance of finding those responsible for the massacre. The talk was followed up with action in September 2004, in the wake of the collapse of the Galeano investigation, when Nisman was appointed to head a Special Prosecutor’s Office that would relaunch the inquiry. This was followed in 2005 by Argentina’s formal recognition before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights that it had failed in its duty to protect those murdered in the attack and properly investigate the crime.

Little is known about exactly why Kirchner chose Nisman, beyond the fact that he knew Nisman was renowned for his vast appetite for work and had made good connections with the intelligence and police forces. That Nisman was Jewish may also have been a factor: What better way to guarantee, in the minds of some people at least, the seriousness of an investigation into the murder of dozens of Jews than to appoint a Jew to lead it?

At the time of Nisman’s appointment, Kirchner reportedly said to him, “This is the person who knows most about the case you are going to work on.” In retrospect, the statement seems somewhat ominous, as Kirchner was referring to Antonio “Jaime” Stiuso, then Head of Counterintelligence at the SIDE (now the AFI), Argentina’s state intelligence service. The SIDE was an organization unreformed (various name changes notwithstanding) since the fall of Argentina’s brutal military dictatorship in 1983. It is subject to little democratic oversight and is often used by the government to pressure judges, businessmen, and journalists who are seen as insufficiently sensitive to government concerns.

In his final television interview, a few days before his death, Nisman said,

I know Stiuso…he is one of the people who knows most about the AMIA case. When Néstor Kirchner put me in charge of the AMIA case Special Prosecutor’s office I already knew [Stiuso]. The AMIA case is an international terrorist attack, I have to work on it with intelligence agencies.

The final decade of Nisman’s life was to involve a lot of work with Stiuso, whose reign over the state’s intelligence service continued all the way up to December of last year, when he was forced to retire in a government purge of the institution. In the days since Nisman’s death, there has been much speculation as to whether Stiuso might have had some role in it. But, as with so many things to do with this case, it’s impossible to say whether there is any truth in it.

In 2006, Nisman formally accused Iran of planning the attack and Hezbollah of carrying it out. He also sought international arrest warrants for a number of senior Iranian officials. After declining to pursue the suspects it believed enjoyed diplomatic immunity, Interpol approved warrants for the arrest of Ahmad Vahidi, Iran’s Deputy Defense Minister at the time; Ali Fallahijan, a former Minister of Intelligence; former government adviser Mohsen Rezaee; Mohsen Rabbani, an attaché at the Iranian Embassy in Buenos Aires at the time of the attack; former diplomat Ahmad Reza Asghari; and Imad Fayez Mughniyeh, who was to die in Syria in 2008. To no one’s surprise, the Iranians indignantly denied any involvement and refused to consider any kind of legal cooperation with Argentine authorities.

Thus began a strange annual ritual, in which President Kirchner used his speech at the United Nations General Assembly to demand that Iran extradite the suspects, while Iran either ignored him or responded with bluster about Zionist conspiracies. Kirchner died in October 2010, having been succeeded in 2007 by his wife, current president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Throughout the early years of her rule, the ritual continued without notable variation.

June 2010 marked the beginning of the end for Nisman in his role as Special Prosecutor for the AMIA massacre. That month, Héctor Timerman was appointed Foreign Minister of Argentina. As would soon become clear, Timerman’s priority would no longer be to bring the AMIA suspects to trial, but rather to cut a deal with Iran and bury the AMIA issue once and for all. Four and a half years later, Nisman would file a criminal complaint against Timerman, President Fernández de Kirchner, and several others for their role covering up negotiations on precisely such a deal with Iran. This was his last official act before being found dead in his bathroom with a .22-caliber bullet in his head.

Héctor Timerman is himself Jewish and the son of Jacobo Timerman, a notable figure in the history of journalism in Argentina and a victim of the 1976-1983 military dictatorship. Interestingly, the young Héctor had initially been an enthusiastic and public supporter of the dictatorship, but changed his views when the blood lust and anti-Semitism of the military government touched his own family and forced it into exile. He lived for many years in New York City, became an American citizen, and worked as a human rights activist. After the return of democracy, Timerman gradually reinserted himself into Argentine politics and journalism.

Though he had previously supported another party, he threw in his lot with the Kirchners shortly after Néstor became president in 2003. They quickly rewarded his timely shift of allegiances, appointing him consul general in New York, ambassador to the United States, and ultimately foreign minister.

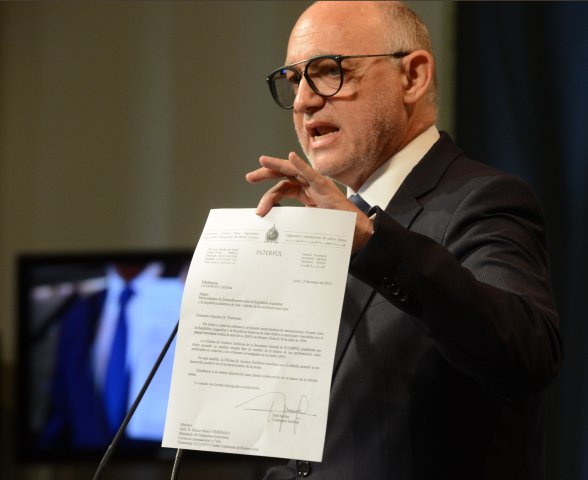

Argentine foreign minister Héctor Timerman displayed Alberto Nisman’s “red alert” against Iranian citizens in order to “expose Nisman’s lies.” Photo: Presidencia de la Nación Argentina / Wikimedia

Timerman’s appointment as foreign minister marked the beginning of a gradual and then rapidly accelerating shift in Argentine policy on Iran and the AMIA issue. Indeed, in his very first press interview upon taking office, Timerman started making eyes at Tehran, expressing distance from and a lack of full confidence in his own court’s extradition requests. He also made it clear that Argentina would not use its influence with allies like President Chávez of Venezuela and President Lula of Brazil, both of whom had good relations with Tehran, to encourage the regime to hand over the fugitives. Nor would Argentina itself make any effort to do so through its influence in international organizations.

Evidence that such talk had become policy was not long in coming: In her annual speech to the UN in 2010, President Fernández de Kirchner offered the Iranian government the possibility of trying the AMIA suspects in a third country if it believed they could not get a fair hearing in Argentina. The Iranians rejected the offer out of hand.

Then, in February of 2011, a strange but very telling episode occurred at Buenos Aires’s main international airport. Irregularities were found in the cargo manifest of a United States Air Force C-17 Globemaster. The aircraft was bringing advisors and equipment intended for members of Argentina’s security forces. Under normal circumstances, apologies would have been offered from one side and perhaps an administrative penalty applied on the other—nothing more would have been made of the matter. After all, the American advisors and equipment had been invited to Argentina. But that’s not what happened. Instead, the Argentine government, with Timerman taking the lead, worked itself into a lather of faux rage about a supposed imperialist incursion into Argentina’s internal affairs, with Timerman making sure he was photographed while personally supervising a detailed search of the aircraft.

Though seemingly inexplicable at the time, the manufactured incident makes perfect sense in hindsight: Argentina was sending a signal of good faith to Iran, with whom it had already entered into negotiations. And it might not be going too far to say that Timerman was trying to set the minds of his new interlocutors at ease regarding any worries they might have had about negotiating with a Jew. He was willing to stage the performance at the airport in order to show them that he was every bit as suspicious of the United States as they were, or at least was willing to pretend to be when it suited him.

In this context, the scandal that would later emerge regarding Fernández de Kirchner and Timerman’s attempted rapprochement with Iran, and Nisman’s eventual criminal complaint against them, begins to seem less surprising than inevitable.

On March 26, 2011, veteran journalist Pepe Eliaschev broke a huge story in Perfil, a Buenos Aires newspaper. He claimed that the government was negotiating a secret deal with Iran that would involve abandoning any attempt to have the AMIA fugitives extradited to Argentina. In exchange, Iran would agree to improve commercial ties between the two countries.

It took the normally loquacious Timerman a whole ten days to respond. When the response came, it was full of scorn for Eliaschev and even included a reference to the Torah, but contained no direct denial of the allegations.

Eliaschev was vindicated nearly two years later. On January 27, 2013, President Fernández de Kirchner unleashed a storm of tweets and a note on her Facebook page, all confirming that Argentina had cut a secret deal with Iran that settled the extradition dispute. The two countries were to set up a joint commission comprised of jurists from both nations—with the participation of a few others from third countries—in order to “examine the documents presented” by the two sides. The proceedings of the commission were, naturally, to be held in Tehran. The Argentine court would be able to talk to the suspects; but only in Iran, and it could not formally question them under oath. At the end of the investigation, the commission would supposedly draw up a report that the parties would bind themselves to “take into account.” The reaction in the Iranian state media indicated that Tehran saw the agreement as a total abandonment of Argentina’s extradition request; indeed, as Argentina’s abandonment of any accusation of Iranian involvement in the AMIA massacre and a commitment to jointly investigate the murders all over again from the start.

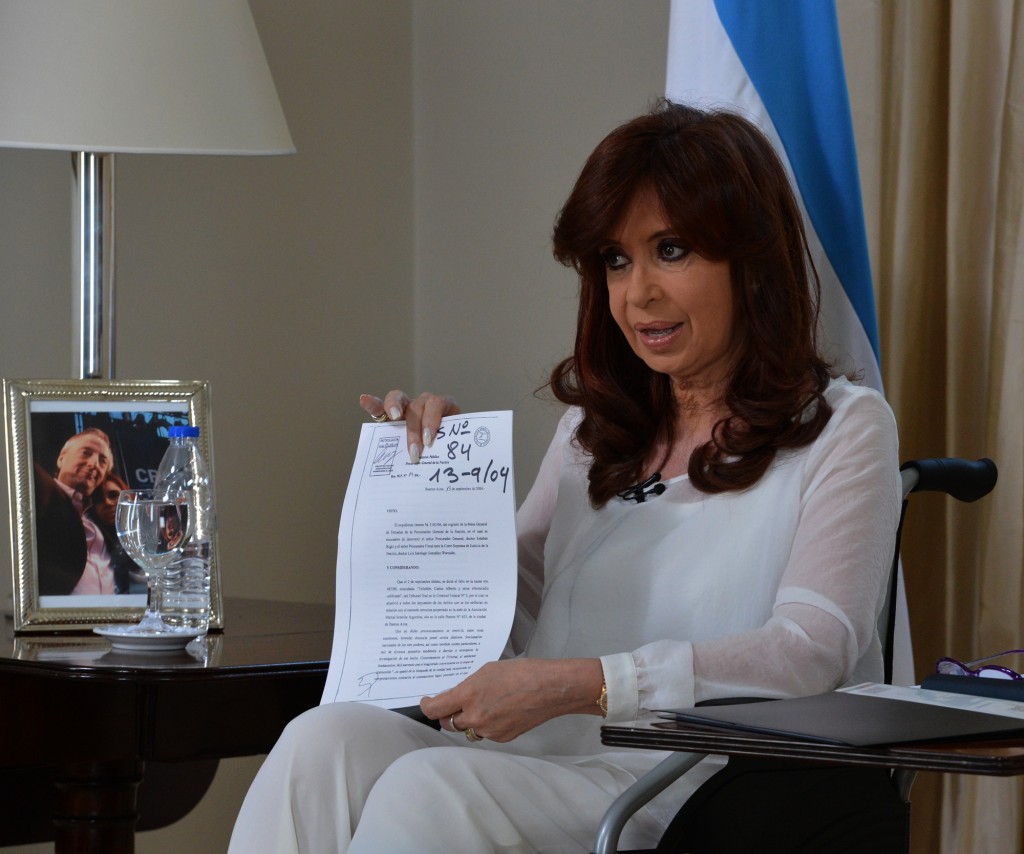

Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner appears at a concert, May 25, 2014. Photo: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación Argentina / flickr

Just over a year later, a federal court struck down the pact on the grounds that it represented a breach of the constitution; and, by that stage, the Iranians themselves had lost interest in ratifying it. Thanks to Nisman’s investigation we now know why. All that the Iranians were really interested in was Argentina’s agreement to drop the international arrest warrants against their officials. Since Nisman’s death, the Argentine government has repeatedly denied this, but it is obvious from statements made by Iran’s state media that it was the case. When it became clear to the Iranians that the Argentine government did not have the power to grant this concession—only Judge Rodolfo Canicoba Corral, who had signed off on the arrest warrants, could do that—the Iranians declined to pursue the matter any further.

The motivations behind the Kirchner government’s turn to Iran are not at all clear. Though the economic practicality of the “oil for grain” deal posited by Nisman has been called into question, it seems likely that some of those active in the negotiations saw improved relations with Iran as an opportunity to open up exciting new business opportunities, especially for themselves. Another relevant factor seems to have been Timerman’s personal ambitions, which are his most notable attribute—along with a level of obsequiousness toward those in a position to further his ambitions that is legendary in the halls of power in Argentina. In addition, President Fernández de Kirchner appears to be both less cautious about and more permeable to the anti-Western discourse of some of her supporters than her late husband and predecessor.

In the wake of Nisman’s death, President Fernández de Kirchner defended the pact to the hilt in her televised remarks to the nation on January 26, 2015. Indeed, she boasted of the scale of the achievement, saying, “We managed to get the Islamic Republic of Iran to agree to sit down to discuss a Memorandum of Understanding for Judicial Cooperation.” But when she referred to the wave of hostile reaction to the pact that followed the initial announcement, mainly but not exclusively from Jewish community organizations, her rhetoric took a darker turn. “Se desataron todos los demonios,” she said—literally, “All the devils broke loose.” She used almost exactly the same words in her speech to the UN General Assembly in September 2014: “Se desataron los demonios internos y externos”; literally, “All the internal and external devils broke loose.” We are permitted to speculate as to the identity of the “devils” the president was talking about.

When the news broke on January 12 that Nisman had filed a criminal complaint against Fernández de Kirchner and Timerman regarding their negotiations with Iran, it came as a shock to the whole political class in Argentina. In retrospect, it should not have done so. Nisman’s fate as Special Prosecutor for the AMIA case had been sealed from the moment the secret negotiations began. From that point on, the objective of the exercise was to normalize relations between Iran and Argentina, rather than bring the accused before a court of law.

Considering the phone taps that Nisman had access to, he must have known about these negotiations from the start, or nearly so. Yet he said nothing. Perhaps he thought the pact would never pass a court challenge. If so, he was proved right. Or perhaps he simply didn’t want to abandon his position knowing that it was bound to be occupied by someone completely dedicated to the interests of the government rather than those of justice. The four prosecutors that have been appointed to replace him match this description exactly. In the context of current tensions between the Argentine government and the federal judicial system, Nisman may have received information that he was about to be removed from his post, and decided to go forward with his allegations in order to stay the government’s hand.

Whatever the reason, go forward he did; and, a few days later, he was rewarded with a bullet in the head. It may have been fired by the Iranians, or by a faction of the local intelligence services; either one acting to protect its government by shutting him up or one acting to cause a political crisis for its government by forcing it to take responsibility for the death of its accuser. One must admit that it is also impossible to completely discount suicide; a suicide induced by who knows what pressures and threats. In any case, the responsibility lies with the government: It failed to protect the life of a key public servant at a time when it should have been particularly concerned for his safety.

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner announces the dissolution of the Secretariat of Intelligence, January 27, 2015. Photo: Presidencia de la Nación Argentina / Wikimedia

For Argentina, the repercussions of Nisman’s death are disturbing, to say the least. It leaves little doubt that Argentina is in the hands of rival intelligence agencies and security forces, each riven by factionalism, always flush with money and willing to do the bidding of its patrons— usually the executive branch—and all constantly monitoring the activities of ordinary people. It is not difficult to imagine the influence of foreign intelligence agencies either. Indeed, there can’t be many other countries whose sovereignty is easier to violate with impunity. And perhaps it’s better not to even speculate about the relationship of Argentina’s legions of spies and policemen with political parties, trade unions, the business sector, and civil society actors in general.

Why Nisman chose to take on all of this must remain as mysterious as his death. Perhaps he had simply become too attached to the inside information he was receiving about powerful men and women. Perhaps he became too comfortable with navigating the dark waters of local and international spies and secrets. Perhaps he became too attached and too comfortable for his own good. This is not to degrade Nisman’s memory. There’s no need to sanctify the man in order to be horrified by his death, and profoundly concerned about what it says about democratic government in Argentina more than 30 years after the return of democracy.

Most of the time it is possible to ignore all of this and get on with life as if we lived in a normal country, ignoring its real structures of power. But Nisman’s violent demise makes it impossible to do so, at least for the time being; after which, more quotidian worries will likely overwhelm us once more.

The death, indeed the likely assassination, of Alberto Nisman may remain as unsolved as the case he died investigating. But one thing is crystal clear: The lives of Nisman, Timerman, and the AMIA victims tell us something about the worth of Jewish lives in Argentina.

Timerman frequently mentions his Jewishness and regards himself as an example of how good things are for Jews in Argentina. In many ways, he’s right about that. He is foreign minister, after all. Axel Kiciloff, the economy minister, is also Jewish. He is believed to be a particular favorite of President Fernández de Kirchner, who appears to believe that Jewish people are possessed of quasi-magical qualities, making it a good idea to have some of them around. In her initial reaction to Nisman’s death, she asked how anyone could believe that Timerman, who “professes the Jewish faith and is Jewish”—to use her bizarre construction—could possibly have done anything illegal during the negotiations with Iran. Timerman too has never been slow to bring up his Jewish origins whenever the government’s relations with Iran have been questioned.

It would be interesting, however, to know what he feels, if anything, when he is referred to in one of Nisman’s phone taps as a “fucking little Jew” by Jorge Alejandro “Yusuf” Khalil, one of Tehran’s local contacts in Argentina and a key figure in the backchannel negotiations with Tehran.

Nisman was also Jewish, but made no particular fuss about that fact. His enemies, however, never forgot it, and the unceasing flow of death threats he received rarely failed to include a cataract of anti-Semitic abuse. When he went public with grave allegations that the Argentine government had broken the law in order to exculpate the murderers of dozens of its citizens, and had done so through a pact with one of the most anti-Semitic regimes on earth, it didn’t take long for a bullet to end his life.

As for the AMIA victims, theories abound regarding the precise motivation for Iran’s decision to carry out the attack. Some say it was Argentina’s refusal to sell nuclear technology to the Islamic republic. Others claim it was revenge for Israel’s assassination of Hezbollah leader Abbas al-Musawi. There might be a simpler explanation: Iran and Hezbollah saw an opportunity to murder a large number of Jews with little risk of ever being called to account. The dizzying incompetence of Argentina’s security forces, the unsupervised local intelligence services—none of them known for being friends of Argentina’s Jewish community—and a president not famed for his personal honesty must have made the AMIA building a very tempting target.

The truth is, nobody’s life is worth much in Argentina. Trains crash, aircraft burn and fall out of the sky, music venues fill with asphyxiating smoke, the provincial security forces do as they please with the scattered and starving remains of Argentina’s indigenous population, and it’s rare that anyone has to pay a price. Certainly, the powerful almost never do. But what the AMIA attack, the failed investigations, and now Nisman’s death show is that, regardless of the number of successful Jewish people in Argentine society, the lives of this country’s Jews are worth less than most.

![]()

Banner Photo: Presidencia de la Nación Argentina / Wikimedia