An emerging movement of ultra-Orthodox Jews seeks to break the cycle of pious poverty that grips their people and divides a country.

On the streets of Tel Aviv and Ramat Gan, you can see men wearing black velvet skullcaps and blue shirts. Their appearance is similar to that of the ultra-Orthodox—or “Haredim,” as they are called in Israel—often seen in Jerusalem and Bnei Brak. But there are subtle yet important differences. These men are the “working Haredim,” and they represent a significant change in the Haredi community.

Today, Israel’s Haredi population is at the center of an acrimonious domestic debate, which at points has grown so loud that is has threatened to replace the peace process as the most controversial issue in Israeli politics. There are good reasons for this. Unlike most Israelis, the Haredim are largely exempt from the military draft, they receive special tax breaks, enjoy copious welfare benefits, and have the lowest rate of workforce participation among Jewish Israelis. The result has been a national backlash that reached a fever pitch in the last Israeli election, after which the second—and fourth-largest parties—Yesh Atid and Jewish Home—refused to join the governing coalition unless the Haredim were excluded.

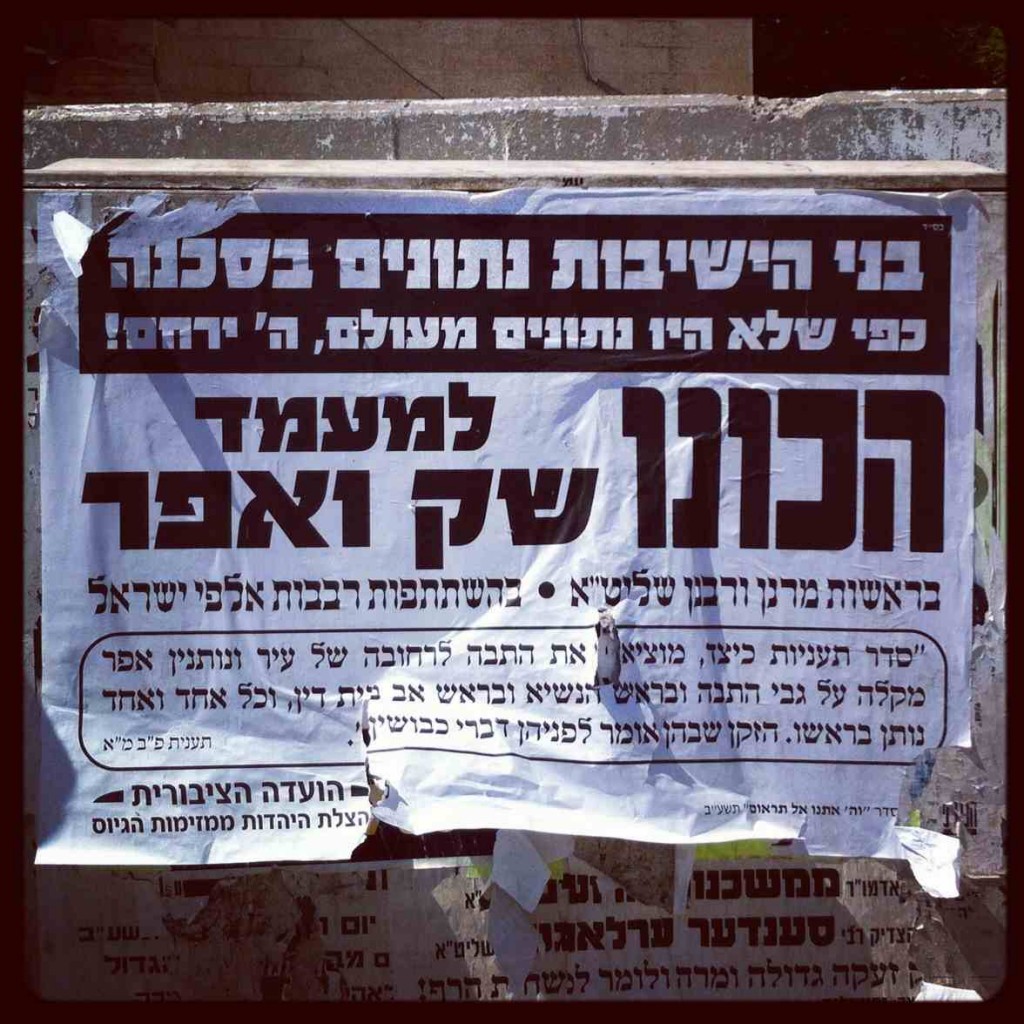

“Prepare your sackcloth and ashes.” Poster calling for protest against conscription.

Photo: Sam Sokol

For the most part, the Haredi leadership and many of their followers have ferociously resisted any change in the status quo. Unseen by many observers, however, what some have called a “silent revolution” seems to be taking place. A somewhat amorphous and ill-defined group known as the haredim ha’hadashim, or “New Haredim,” is emerging. They forgo the community’s traditional full-time Torah study, enter the workforce, and attempt to engage with the larger society around them without compromising their Haredi identity. And they may constitute a political force capable of bridging the rift between the Haredi community and the rest of Israel.

By some estimates, including data extrapolated from voting records, up to ten percent of Israel’s ultra-Orthodox may be New Haredim. Another ten percent may be silently sympathetic to them, despite the intense social pressure to shun the group and its ideas. During the last Israeli elections, the largest Haredi political parties—the Sephardi Shas and the Ashkenazi United Torah Judaism—vied to gain the support of a small political party called Tov, which represents the New Haredim. Some researchers believe that they constitute something like Israel’s first ultra-Orthodox middle class.

But the New Haredi movement is also considered a threat by the ultra-Orthodox establishment. The newspaper Yated Nee’man, which is widely considered the mouthpiece of the “Lithuanian” ultra-Orthodox leadership, has vigorously condemned the New Haredim, calling them a threat to the status quo. In a recent editorial, the paper said,

While it is clear that working for one’s livelihood does not disqualify a person as a “Hareidi,” to a true Haredi his career is no source of pride for him. If circumstances force him to leave the study hall and seek a livelihood, he will do so against his will and not proudly declare that he is a “working Hareidi.”

The term “Haredi” comes from the Hebrew word for “trembling” or, depending on the context, “anxiety.” It is a direct reference to the fear of God; that is, the fear of transgressing the laws of the Torah. As a result, traditional Jewish law as interpreted by the Haredi leadership lies at the heart of ultra-Orthodox life. The Haredi community, which now numbers around 700,000 out of the country’s approximately six million Jews, is far from a majority; but according to the Israeli Education Ministry, fully one-third of Israeli kindergarteners attended Haredi schools in 2009. And that number was the result of a rapid demographic surge, growing 26 percent in eight years.

It also represents a looming social crisis. The vast majority of Haredi students do not receive even the most basic secular education, foregoing the core curriculum standard in Israel’s secular and religious-Zionist schools in favor of pure Torah study. As the Haredi population increases, many experts have begun to warn of the possible economic consequences of a large and growing demographic that lacks the basic skills necessary for employment and must depend on state welfare.

The New Haredim represent a different path; one that is personified, in many ways, by two men from the mixed secular-religious city of Beit Shemesh. One is Rabbi Dov Lipman, an American immigrant from Silver Spring, Maryland. He was recently elected to the Knesset as a member of the Yesh Atid party, which is dedicated to “equalizing the burden” shared by secular and religious Israelis.

Thousands of Haredim rally in Jerusalem against drafting Yeshiva students, June 2012. Photo: Yonatan Sindel/Flash90

The other is Rabbi Shmuel Pappenheim, a member of the extreme Toldot Aharon Hasidic sect and the former spokesman for Edah Haredit, an anti-Zionist Haredi organization. Though he doesn’t dress the part of a New Haredi—many of whom wear blue dress shirts instead of the white shirts typical of the community— he certainly acts the part.

Several years ago, Pappenheim opened a vocational training center in Beit Shemesh’s Kiryah Haredit neighborhood. His intention was to aid Haredim who find themselves forced to enter the workforce by economic circumstances. “Avreichim,” or full-time students at yeshivas for married men, began to take advantage of the program, which empowered them to rise out of the poverty in which many of Israel’s Haredim find themselves trapped. Taking this kind of action was a bold, even risky, step; but on a practical level the center was clearly thriving.

It wasn’t long, however, before the backlash hit. Extremists belonging to a sect known as the sicarii broke into the center’s computer lab and poured a mixture of oil and decomposing fish on to thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment. Not long after, Pappenheim was severely beaten while attempting to enter a synagogue.

Since then, Pappenheim and Lipman have begun working together, despite a long history of personal differences, particularly regarding the use of violence by extremist sects. Lipman, who was placed on the Yesh Atid list because of his work on anti-violence and diversity programs, is a good example of the American model of ultra-Orthodoxy, which generally allows and even encourages its members to work. Lipman, the son of a judge, spent years in yeshiva earning his ordination, but was also fully engaged with American culture and academia, earning a master’s degree in education from Johns Hopkins University alongside his religious studies.

Israel’s ultra-Orthodox culture is fundamentally different from that of the Diaspora. Israel’s Haredi community has its roots in the poverty-stricken Jewish community of pre-state Palestine, known as the Old Yishuv. This community mainly subsisted on charitable donations from Jews living abroad, who believed that there had to be a group—however small—living and studying Torah in the land of Israel. While the Jews of the Diaspora worked for a living, they also believed that the Jews of Palestine neither could nor should support themselves in the same way. Thus, studying Torah full-time became inherent to the local religious culture of Palestine, which was not the case anywhere else.

After the Holocaust and the founding of the State of Israel, Haredi leader Rabbi Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz, also known as the Hazon Ish, made a famous deal with then-Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion that exempted several hundred ultra-Orthodox students from army service. This was done in order to salvage a tradition that had been decimated by the Holocaust. As the ultra-Orthodox community began to grow in numbers, Israel found itself suddenly faced with a community of thousands who were exempt from military service and solely dedicated to full-time, lifelong Torah study. In the 1970s, as the Haredi parties gained strength in the Knesset and became the “natural” partner of the newly triumphant Likud party, the community began to change.

Rabbi Natan Slifkin, a self-declared “post-Haredi” Jew, Orthodox rabbi, and author, notes in his The Making of Haredim,

The ultimate step in the evolution of the kollel [a religious school for married men], which spread in the latter part of the twentieth century, was its presentation as an expectation of every young man in the Haredi community. In more moderate Haredi circles in the United States, this is only expected for a year or two following marriage, while in the rest of Haredi society in the U.S. and Israel it is expected to continue for at least a decade or two, if not indefinitely.

This change is reflected in Haredi employment numbers. As recently as 1979, almost 90 percent of ultra-Orthodox Jewish men were employed. In 2011, according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, that number had dropped to under 50 percent.

Over the past decade, the situation has begun to change. The first and arguably most significant development was the creation of the “Nahal Haredi,” an IDF battalion for Haredi soldiers, in the late 1990s. Nahal Haredi provides a strictly kosher, gender-segregated environment that allows young Haredim to serve in the army while strictly adhering to Jewish law. Though it is not as socially acceptable in the Haredi community as it is in secular society, the sight of ultra-Orthodox men in uniform is no longer the unthinkable disgrace it once was.

Shortly after, a number of ultra-Orthodox colleges were opened to provide professional training in a Haredi religious environment . At the same time, companies like the Modi’in-based high-tech company Matrix created programs to encourage the employment of Haredi women, who often become the family breadwinners while their husbands study Torah. There is now even a Haredi High Tech Forum.

Dov Lipman has said that the entrance of Haredi women to the workforce, together with rising Internet penetration and the resulting introduction of new ideas into the Haredi community has led to social tensions. This often occurs in Haredi marriages when the wife works and brings home a more modern outlook that clashes with her husband’s insular ideology.

Nonetheless, says Lipman, young Haredim seek him out on a regular basis, bitterly complaining about their situation and asking him to continue his push for change in a community where change, when not totally anathema, is often slow to occur. “In time,” Lipman predicts, “as more and more go to work, things are going to change. As more Haredi men go to work and they see they can combine Torah with being part of the world, and they see that secular Jews aren’t the devil and can get along with each other, slowly but surely I think that people will feel more comfortable.”

In a paper on the New Haredim, Israel Democracy Institute researchers Lee Cahaner and Haim Zicherman note, “Over the last decade in Israel, cultural and economic developments and changes in leadership have been weakening the ‘society of learners’—in which ultra-Orthodox Jews devote themselves to full-time study rather than joining the workforce—and strengthening the individual Haredi. At the same time, however, a significant sub-group has begun to emerge: a Haredi middle class.”

Providing accurate numbers of the New Haredim is difficult, says Zicherman. But the rise of the Tov party shows that they have begun to coalesce into a conscious political and social movement. “We know it’s something real,” says Zicherman, “because now they have started to organize.”

The results of recent local elections—the first in which the Tov party competed—provide some insight into the issue. While the leaders of Tov have said that their supporters number as many as 10,000 out of a community of approximately 700,000, Zicherman isn’t so sure. However, he says, “I am sure that we are speaking about thousands of people,” because the party garnered significant support during the last elections. “In Beitar it’s one out of 15 Haredim and in Beit Shemesh it’s one out of ten.”

Tov party spokesman Yitzchak Horovitz agrees. “We carried out a survey a few months ago,” he says, “to check how much of the populace supports our ideas and it was about 20 percent of the Haredi population.” But out of that twenty percent, he notes, only half is actually willing to actually vote for Tov.

Though he is one of the most public faces of the New Haredim, Horovitz doesn’t like the term. He prefers “working Haredim,” noting that most of the party’s supporters are staunchly blue collar. But whatever terms he employs, Horovitz insists that Tov is a growing movement. “There are more studying in academic institutions, more people going out to work, and more people finding that they cannot sustain the [status quo].”

In this Horovitz is undoubtedly correct: On the one hand, the community is one of the poorest in Israel; on the other, secular Israelis just elected a government coalition that excludes the Haredi parties with the explicit aim of “equalizing the burden.” Economically and politically, the status quo is unsustainable.

Dov Lipman believes that the problems of the ultra-Orthodox community are ultimately caused by the concept of da’as torah, which holds that the senior rabbis of the community exercise absolute authority over all community issues. “If you sit down with a Haredi quietly in a room and say to him, do you see something wrong with combining Torah and sustaining your family properly? Most of them will tell you—in that setting—’I do not see a contradiction,’” Lipman says. “When you ask why they do not support such a societal structure, they will explain that they do not act on this belief because of da’as torah. So as long as that’s in place it’s going to be very hard for a massive type of change.”

Recently, Lipman held a secret, middle-of-the-night meeting in a Bnei Brak parking lot with a number of 18-year-old yeshiva students. The young men told him that they were actually interested in doing military service within a religious framework. “They weren’t waving the flag for Zionism, but they were invoking the land of Israel, saying it’s important and we want to contribute our part.” Nonetheless, “they said the pressure from above is so strong that it is very hard to have the courage to do it.”

In the face of their community’s growth and the concomitant rise in poverty, Lipman says many Haredim

began to question the system, which has told them that everybody is just supposed to sit and learn Torah. I think there is some awareness of what I would call the ‘American Haredi,’ where they see people that are able to be Haredi and combine that together with working and being part of society, and I think that has had some level of influence as well. But the primary [reason] is one of need.

What is interesting about the New Haredim is that while their numbers are small relative to the larger ultra-Orthodox population, they have grown tremendously over the last decade. In addition, they appear to have large numbers of quiet supporters within the mainstream ultra-Orthodox community. Lipman adds: “The quiet sympathizers are a huge number. Let’s remember, it takes a tremendous amount of courage to be that way. It means it could impact your children and their schools. It could impact your daughters in terms of shiduchim [arranged marriages]. It takes a tremendous amount of courage to be someone who is openly embracing this new approach. So it’s a very small number…. Many of them couch it in [language such as] ‘I have no choice I have to go out and work but not as an ideology that I believe this is the way it should be.’ But that’s going to change.” Asked if there is any chance that a new rabbinic leadership could emerge that supports the New Haredim, Lipman replies that “the issue of the gedolim [rabbinical leaders] is very largely the askanim who surround them.” Askanim is a Hebrew term that refers to the community activists and assistants who surround the leading rabbis and act as a buffer between them and the communities they lead.

“They are totally controlled by people around them, and that’s the biggest problem,” Lipman says of the rabbinical leadership.

That’s why it’s going to be hard, because the moment anybody emerges with another kind of ideology they are branded immediately as being outside the camp and as not being Haredi. That happens immediately and there is a massive campaign against any person who voices anything different. So the chance of the new gedolim, so to speak, developing to lead this way, I don’t see that happening.

Despite severe censure from leading rabbis, however, Tov party members, and by extension the new Haredim, have not been deterred. While they have suffered discrimination in school admissions and potential marriages for their children by coming out publicly with their views, they have stood firm and seem to have chosen their own, more accommodating rabbis.

Aryeh Goldenberg, another spokesman for Tov, says that he follows rabbis who recognize the “need and the importance of a person who has to go out and work, especially when he has a family to feed.” Citing the Talmudic adage, “Any study of Torah when not accompanied by a trade must fail in the end and become the cause of sin,” Goldenberg said that the idea that “every Jew has to be a contributor to the society and not be a burden” is a fundamental principle of Judaism.

Dov Lipman says that due to the delegitimation of New Haredi rabbis, the only chance for communal change rests with the common people. “There is apparently a rising interest among Haredim in [academic] programs,” comments Dan Ben-David, executive director of the Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel, “but the bottom line is that it’s like a rearguard action. As long as the children don’t start receiving a basic education we are going to have to continue paying a huge premium on doing this sort of back door [action], not to mention the high cost because of the inefficiency involved.” Like Zicherman and Cahaner, however, Ben-David says that there is “quite a bit of anecdotal evidence of a regime change, especially among the younger Haredim. Having said that, the primary tool that they need—education—is not one that’s on their table at this point. It’s not possible to talk with any of the major Haredi leaders about giving their children at least some kind of a solid education in the basic subjects all the way through the end of high school.”

Lipman: It’s not possible to talk with any of the major Haredi leaders about giving their children a solid education through high school.

Corrine Sauer of the Jerusalem Institute for Market Studies, a think tank that studies social progress in Israel, notes that change is unlikely so long as Israeli tax law provides certain groups with financial incentives to avoid employment. In many cases, ultra-Orthodox men who wish to join the workforce but lack the education needed to obtain a decent wage will actually lose money by getting a job.

Lipman himself has begun to initiate such changes. Together with Labor Party legislator Eral Margalit, he has established a Knesset committee dedicated to integrating Haredim into the workforce and, he says, there is a groundswell of silent support for his efforts. Through a combination of the emergence of the New Haredim and such outside pressure, change may come.

***

Editor’s Note: This is a modified and updated version of a piece that first appeared in The Jerusalem Post.

Banner Photo: Uri Lenz/Flash90![]()