Well-intentioned European laws prohibiting hate speech have only helped the most hateful. A new approach is needed.

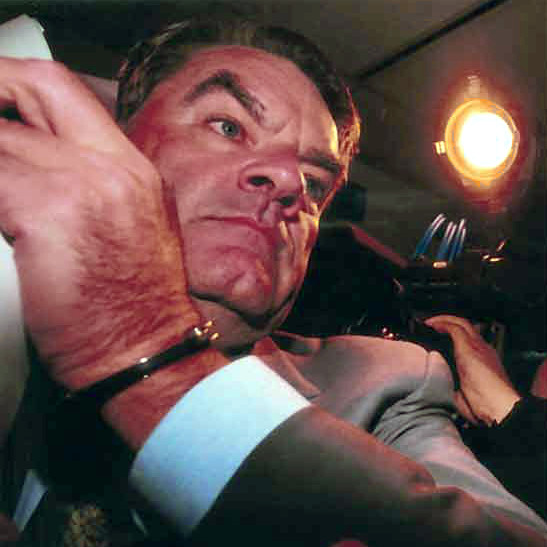

Dieudonné M’bala M’bala—who by all accounts used to be a comedian before taking up Jew-hatred full-time—is the living embodiment of the new anti-Semitism in France, “a union of Holocaust denial, anti-Zionism, and competition among victims,” as the philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy sketched out rather perceptively his 2008 book Left in Dark Times. “We have nothing against Jews, the new anti-Semite protests, as always,” Lévy wrote. “What we’re against is people who traffic in their own memory and push out the memories of others for the sole purpose of legitimizing an illegitimate state.”

In 2008, the inventor of the quenelle—the inverted Nazi salute misleadingly characterized as an anti-establishment gesture—was giving a stand-up performance in Paris when, as The New York Times reported, he invited a Holocaust denier up onstage “to receive a prize from an actor dressed in striped pajamas resembling a concentration camp uniform, with a yellow star bearing the word ‘Jew.’ The prize was a three-branch candelabrum with three apples on top.”

In November, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg ruled that the laws governing the freedom of expression did not protect Dieudonné’s routine. The scene in question “could not be construed as entertainment” and instead “resembled a political meeting that, under the pretext of comedy, promoted Holocaust denial” as well as anti-Semitism. The court upheld the 2009 conviction and €10,000 fine Dieudonné received from a French court in relation to that performance.

2015 was a particularly litigious year for Dieudonné. In March, he received a two-month suspended sentence in France for writing on Facebook, in the wake of the terror attacks on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and the Hyper Cacher supermarket, “Tonight, as far as I’m concerned, I feel like Charlie Coulibaly.” Dieudonné mixed together the popular slogan “Je suis Charlie” with the name of Amédy Coulibaly, who killed four Jews in the market attack. Again in November, a Belgian court sentenced Dieudonné to two months in prison for incitement to hatred over racist and anti-Semitic comments he made during a 2012 show in Liège.

The fate of Dieudonné M’bala M’bala is indicative of Europe’s censorious instinct. For the sake of the common good, European governments and courts have sought to place clear parameters on the freedom of speech: for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, and for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, as it is stated under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In France, this would include anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and the denial or minimization of crimes against humanity.

Yet Dieudonné thrives. Certainly, he is not a mainstream voice, but a decade of court action against him has not diminished him. Indeed, the perception of his so-called persecution by the state has won him a new audience on the political and social margins of French society, “with a cult-like following on stage and via the Internet, where his satirical videos stand out among a rash of new anti-Semitic Web sites in France,” as The Washington Post reported. “He has traded larger venues for relatively smaller theater spaces where he is filling seats with fans across racial, political and socioeconomic spectrums.”

Dieudonné is also indicative to the new challenge to Europe’s regulations on the freedom of speech. Laws that were created and framed to deal with one threat—the possibility of a second coming of Nazism or another far-Right ideology—are being undermined by newer ideologies and technologies: the new anti-Semitism, political Islamism, and the ideology of jihadism and terrorism, all disseminated largely online. In the wake of the January and November 2015 Islamist terror attacks in Paris, and with heightened insecurity around the continent, the question remains whether to tighten existing regulations on free speech or conceive of a new attitude to the concept.

Either way, the current approach to the freedom of expression in Europe is not working. These laws give credence and cachet to the often self-pitying narratives of those who would propagate anti-Semitism, promote the boycott targeting Israel, or deny the Holocaust, that somehow they are saying the things that cannot be said. A ban on bad speech is but a substitute for an open confrontation with it. We are weakened as a society by laws that tell us what we can or cannot hear or say. There is also the question of how relevant such laws are in an age where the internet has broken down borders and speech knows no national boundaries.

It says something about attitudes to free speech in Europe that the most frequently cited dictum to come from European philosophy on the matter is in fact a misattributed quotation. It is often said that Voltaire once proclaimed, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it,” although he never actually did. (Not to say that Voltaire was not an advocate of free expression and tolerance between the faiths, but that line in fact comes from his English biographer, Evelyn Beatrice Hall.)

The roots of the present European interpretation of the right to free expression are to be found in the great English liberal tradition, one that begins with John Milton’s Areopagitica: “Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.” Arguing in favor of unlicensed printing, Milton wrote:

And though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously, by licensing and prohibiting, to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?

“Wrong opinions and practices gradually yield to fact and argument,” John Stuart Mill wrote in On Liberty, further developing liberal thought on free expression. “If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had that power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

For, “if the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.” Mill’s caveat was that the prevention of harm to others was a legitimate reason for the exercise of power over others, but “over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”

Over time, and concurrent to the development of the idea of the social contract between citizen and state—the sacrifice of some of our liberties in order to preserve others for the sake of the common good—the notion that speech can be regulated in order to prevent harm has become ever more prominent in European thinking and law.

Over the last century, above all else, this has a great deal to do with the Second World War and its aftermath, the crucible in which current European law on free expression was shaped. As part of the denazification process, laws against so-called “reactivation” were introduced in Germany and Austria, which proscribed not only neo-Nazi and other far-right organizations, but the public dissemination of their propaganda and symbols, including flags, insignia, uniforms, slogans, and forms of greeting. (The German and Austrian laws were later expanded to include bans on the denial of the Holocaust.)

The notion that speech can be regulated in order to prevent harm has become ever more prominent in European thinking and law.

The European Convention on Human Rights, drafted in 1950 and ratified in 1953, includes the right to freedom of expression but—in stark contrast to the American idea of unfettered free speech underpinned by the First Amendment—also stressed that this right comes with certain “duties and responsibilities” and “may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society.” In countries across Europe, this has come to mean, among other things, the introduction of national laws on hate speech, intended to establish the parameters of acceptable discourse in order to prevent harm to racial, religious, and sexual minorities.

In France, in addition to several actions taken against Dieudonné, the highest court of appeal recently upheld several convictions against anti-Israel boycott activists, asserting that their loud and intimidating protest outside a supermarket in Mulhouse constituted a form of incitement and discrimination. The protesters picketed the supermarket wearing T-shirts that declared, “Long live Palestine, boycott Israel,” distributed leaflets reading, “Buying Israeli products means legitimizing crimes in Gaza,” and tried to forcibly clear shelves stocking Israeli goods. The court ruled that such actions “provoke discrimination, hatred or violence toward a person or group of people on grounds of their origin, their belonging or their not belonging to an ethnic group, a nation, a race or a certain religion.”

The promotion of boycotts against Israel has been rendered illegal in France by virtue of this ruling, but the boundaries drawn are not always so strict. In 2002 a French court acquitted the writer Michel Houellebecq of a charge of inciting racial hatred over his novel Platform, which depicted Islam unforgivingly. Islam is “the stupidest religion,” Houellebecq had said; the court determined that this was acceptable speech, since it constituted criticism of a religion and not a race or people.

The boycott movement in France is now subject to a kind of prior restraint—censorship before the expression has taken place. This is built into European laws on the freedom of speech, not just in terms of hate speech regulations but the banning of those from European soil who might say something that would contravene said laws, on the basis that allowing someone the mere possibility of breaking the law might upset the common good. In July 2013, British laws in that direction were applied against Pamela Geller, founder of Stop Islamization of America and proprietor of the Atlas Shrugs blog, and her collaborator Robert Spencer.

Geller was due to address a rally of the far-Right English Defence League in Woolwich—where two months prior the British solider Lee Rigby had been murdered in the street by Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale—but fell afoul of British authorities for her past statements on Islam. “There are no moderates. There are no extremists. Only Muslims,” she has said. “Devout Muslims should be prohibited from military service. Would Patton have recruited Nazis into his army?”

It goes on. The Bosnian genocide was a fabrication. Secular, democratic Kosovo is a “militant Islamic state in the heart of Europe.” President Obama is the secret “love child of Malcolm X.” To have said any of this on British soil, the government ruled, would have constituted “committing unacceptable behaviors,” and with that Geller and Spencer were barred. (Because of his statements about Islam and his proposal to bar Muslims from entering the United States, the British parliament recently debated whether or not to bar GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump from the UK, too. Parliament does not have the authority to do this—only the Home Secretary does—and so the whole debate was merely a spectacle of moral posturing.)

But perhaps the most overt way European countries have attempted to exercise prior restraint is in proscribing the denial and minimization of the Holocaust. The early 1990s witnessed the passage of a rash of acts, amendments, and constitutional laws designed to render illegal questioning the existence or extent of the midnight of the European twentieth century. Today, Holocaust denial is prohibited in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic.

Laws prohibiting Holocaust denial are well-meaning but have only served to popularize and make martyrs of those who “speak truth to power.”

In 2007, a European law was passed that would mean jail time for those who incite violence by “denying or grossly trivializing crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.” However, the law is not enforceable in those European states that do not have a Holocaust denial law on their own statute books. Northern European countries like the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Sweden have traditionally been reluctant to legislate on this matter.

Laws prohibiting Holocaust denial have been used to prosecute not only Dieudonné M’bala M’bala but Jean-Marie Le Pen, the elderly racist and former leader of the French Front National. In France, Le Pen was prosecuted and fined under the Gayssot Act on denial of crimes against humanity for reducing the Holocaust to a “detail” in the history of the Second World War. A German court would later prosecute him for the exact same statement, albeit on their soil. In 2008, Le Pen was given a three-month suspended sentence in France for saying the Nazi occupation of that country—during which 76,000 Jews were deported to the gas chambers at Auschwitz—was “not particularly inhuman.”

The most noteworthy instance of prosecution under Holocaust denial law took place in Austria, where in February 2006 the anti-Semitic pseudo-historian David Irving was sentenced to three years imprisonment. In 1989, he had given two speeches on a visit to Austria during which he had denied or minimized the Holocaust: a criminal offence under an Austrian constitutional law passed in 1947 (and revised and extended in 1992). Irving had called for an end to the “gas chambers fairy tale,” claimed Adolf Hitler had helped Europe’s Jews, and said the Holocaust was a myth, The Guardian reported.

After thirteen months in prison, Irving was released and then duly banned from reentering Austria. He is also barred from Italy and Germany due to his views on the Holocaust, and in 2002 was fined several thousand dollars by a German court for asserting a nonsense view, commonly held by Holocaust deniers and other unhinged types, that the gas chambers at Auschwitz were a hoax.

The prosecution of Holocaust denial has a symbolic significance which should not itself be denied or minimized—there is something to be said for a law against Holocaust denial on the continent where the crime was perpetrated—but the outcomes of such interventions, whether against Irving or Le Pen, rarely justify the contravention of the principle of the freedom of speech.

These laws have absolutely failed to eradicate this strain of thought—or rather, unthought—from European society. 11 percent of Western Europeans and 24 percent of eastern Europeans believe the Holocaust to be a myth or exaggeration, the Anti-Defamation League found in 2014. A 2013 survey by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights found that 21 percent of European Jews had heard someone say that the Holocaust was a myth or had been exaggerated in the last twelve months. It’s marginal—but it’s there.

These laws do not address the problem of Holocaust denial but rather act as a sticking plaster, covering up the unhealed, festering wound beneath. Consider that Irving’s statements denying the Holocaust occurred when the Nazi war criminal Kurt Waldheim, who lied repeatedly about his wartime service and connection to the deaths of thousands of Greek Jews during the Holocaust, was the president of that country. When Irving was censored and sentenced to jail, the Alliance for the Future of Austria, the party founded by the fascist Jörg Haider, was part of the government and controlled the Justice Ministry. It wasn’t until six years after Irving was jailed that the name of Karl Lueger, the anti-Semitic former mayor of Vienna, was removed from a section of the city’s most famous road, the Ringstrasse.

The only effective counter to Holocaust denial is knowledge: reconciliation, debate, and education. Today, David Irving is a nobody, an utterly discredited, paranoid, and shambling figure who gives talks to small rooms of weird enthusiasts for his counter-factual apologias for Hitler and Nazism. But that Irving’s reputation is in tatters has little or nothing to do with his thirteen months in an Austrian jail cell and everything to do with the famous British High Court libel trial, which reached a verdict in April 2000, in which Deborah Lipstadt and her team of lawyers and historical scholars successfully proved that Irving was a Holocaust denier.

The presiding judge in that case determined that Irving’s books, diaries, and other public and published utterances proved that he was “an active Holocaust denier” as well as “anti-Semitic and racist.” “There was never any real doubt that [Lipstadt and Penguin, her publisher] would win,” Anthony Julius, Lipstadt’s lawyer in that case, argued in Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England. “Irving’s falsifications and distortions were so egregious, and his animus towards Jews so plain, that he won the case for them.” David Irving was not put down by censorship—quite the opposite, in fact. He was hoisted by his own petard, discredited by his own words and thoughts while attempting to use the British legal system to censor and reprimand another writer.

David Irving is undoubtedly a terrible historian, especially of the Holocaust. Julius makes the case that the only witnesses of the event Irving accepts are those who saw nothing. He would place emphasis on euphemistic or evasive documents while dismissing solid evidence for the Holocaust as falsifications. And, he set an unattainable standard of proof for the existence of the Holocaust. Being a terrible historian, however, is not a crime—or at least it shouldn’t be. For his words and thoughts, no matter now false they are, Irving should never have seen the inside of a jail cell.

As Deborah Lipstadt herself said after Irving was sentenced, “I am not happy when censorship wins, and I don’t believe in winning battles via censorship. The way of fighting Holocaust deniers is with history and with truth.” The same might very well be said of the prior censorship of Mein Kampf, which has just been reprinted in Germany for the first time since the end of the Second World War in a new, two-thousand page critical edition that contextualizes Hitler’s world within a historical examination of the work.

The fate of Mein Kampf is another example of a form of censorship that has outlived its usefulness.

Upon Hitler’s suicide, as a legal resident of Munich his estate—which included the rights to Mein Kampf—was ceded to the state of Bayern. The regional government used its ownership of the copyright on the book to prevent new editions from being printed (though old copies continue to exist in circulation). It is the position of the Central Council of Jews in Germany—and an understandable one at that—that seventy years after the Holocaust, Mein Kampf must remain prohibited, out of a fear that its republication “could potentially fuel ethnic and religious hatred, perhaps even leading to acts of violence,” A.J. Goldmann reported in The Forward.

But the fate of Mein Kampf is another example of a form of censorship that has outlived its usefulness. For one, it is an important historical document that should be available in some sort of critical or annotated edition for journalists and scholars to read, use, and cite. Goldmann quotes the writings of the German historian Eberhard Jäckl in his report, who states that “Perhaps never in history did a ruler write down before he came to power what he was to do afterwards as precisely as Adolf Hitler.”

As to the relationship between the publication of the book and the possibility of a rise in anti-Semitism, that notion presupposes that anti-Semites and those predisposed to anti-Semitism have the ability to read a lengthy screed like Mein Kampf. One cannot help be skeptical about the idea that a two-thousand page annotated edition of a book first published in 1922 would be a potential trigger, the thing that would lead to the radicalization of someone who doesn’t already have Jews on the brain.

This is not just because most anti-Semites can’t read anything longer than a tweet these days. Anti-Semitism itself has moved beyond Hitler. The relationship between the new anti-Semitism—this Molotov cocktail of Holocaust denial, anti-Zionism, and competition among victims—and the German race-and-blood anti-Semitism of Mein Kampf is not dissimilar to the connection between neo-Nazism and Nazism. The new anti-Semitism would not exist were it not for the old anti-Semitism—it is based in part on Holocaust denial, after all—but the new anti-Semites do not look for their inspiration in Mein Kampf. Nor do they necessarily object to Jews qua Jews, so long as those Jews dutifully echo the imperative of removing the State of Israel from the international system of sovereign states.

The new anti-Semite is more likely to read a conspiracy-mongering website like Veterans Today or the blog of Gilad Atzmon, an Israeli-born musician who produces a constant stream of invective against Judaism and Jewish empowerment. He or she will watch Iran’s state broadcaster, Press TV, or the Kremlin mouthpiece Russia Today. Virulently anti-Semitic views can be heard from certain mosque clerics and preachers, as well as on Arabic cable networks. As for rabid and gruesome depictions of Jews and their alleged power, there is a plentiful supply of all this on Islamist social media feeds and in publications like Dabiq, the English-language magazine of the Islamic State. One no longer needs to buy a copy of Mein Kampf.

The contrast between the American and European legal approaches to the freedom of speech is, if anything, a consequence of differing interpretations of the role of the state. But the climate of insecurity across Europe and the growth of online discourse that transcends national boundaries, together with the evolving nature of anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim bigotry, and other forms of racial and religious hatred, call into question whether these different approaches to the freedom of speech can hold. The internet is now the main tool for the dissemination of hate speech and untruths, the radicalization of the vulnerable and the seeking, and the recruitment of those who seek our destruction. The laws on free speech simply cannot keep pace with current developments, resulting in a whack-a-mole approach to going after those who promote jihadism and terrorism online, or incitement to hatred against women, Jews, or the LGBT community on social media.

The prosecution of Dieudonné M’bala M’bala and Jean-Marie Le Pen, David Irving and the boycott movement, and the application of the law against Pamela Geller and Robert Spencer as well as politicians like right-wing Dutch parliamentarian Geert Wilders, makes an important statement about European values. After all, Europe as it is constituted today would not exist were it not for the great tragedy of the twentieth century: the Second World War and the Holocaust. Europe is forever bound to that past, the modern European order having been created precisely in order to prevent a relapse, a second catastrophe.

Part of this responsibility and commitment to the principal of “never again” entails protecting those who were the subject of discrimination, persecution, and extermination before Europe’s zero hour—Jews, and the other victims of Nazism—through laws regulating the freedom of expression. The remit of those laws has expanded, in terms of those who can seek protection under them, as the demographic balance of the continent has changed, to include Muslims and other racial and religious minorities.

These laws have a tremendous symbolic value—one that is so great that its symbolism alone is a good enough reason to keep them in place. One can easily make the case that Europe has made the right decision not to subject Jews to Holocaust denial, Roma to neo-Nazi rallies, immigrant communities to racism, and gays and lesbians to homophobia. But reason would counter that no law abridging the freedom of speech can defeat these prejudices, because no such law can stamp out an idea or cure a pathology.

The regulation of free speech in order to prevent harm has done more harm than good. It gives the power of deciding what is or is not acceptable speech for us to hear, or say, over to somebody else: to a committee, or law, or subsection of a law. It infantilizes us and coddles us. It makes us intellectually lazy because we are no longer used to having to challenge unreasonable and hateful ideas in public if we can merely proscribe them and shut them down. It also makes censorship seem acceptable, provided we are not the ones being censored, to which mutation of safe space policies on British and American university campuses into codes for exercising undue prior restraint are a testament.

In the first act of Robert Bolt’s play A Man for All Seasons, there is an exchange between Sir Thomas More and the biographer William Roper. “So now you’d give the Devil benefit of law!” Roper says to More.

More: “Yes. What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?”

Roper: “I’d cut down every law in England to do that!”

More: “Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat?”

We make ourselves hostage to the censorious instincts of others when we allow for too fastidious a definition of what speech is or is not acceptable. Those in favor of the regulation of free expression in Europe should always consider that while they are seemingly protected for now, they could find themselves among the individuals being censored in the future.

![]()

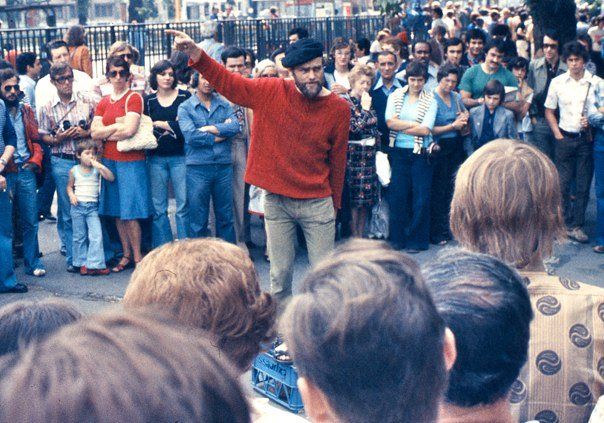

Banner Photo: Red Maxwell / flickr