The claim that Israel is an apartheid state is especially salient in South Africa. And students who don’t toe the party line often find themselves ostracized—or worse.

Speaking up for Israel is an act of supreme bravery in South Africa these days, particularly if you are a member of the ruling African National Congress. After more than two decades in power, the ANC is becoming discernibly more hostile to Israel with each passing year. The small number of activists inside the movement who have questioned this policy have rapidly become political outcasts.

The deep roots of the ANC’s anti-Israel campaign have made it a natural bedfellow of the cacophonous Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement in South Africa. On December 20, 2012, the ANC adopted the Palestinian call for boycott, divestment, and sanctions against Israel as its official policy. A resolution passed by the ANC’s International Solidarity Conference stated, “The ANC is unequivocal in its support for the Palestinian people in their struggle for self-determination, and unapologetic in its view that the Palestinians are the victims and the oppressed in the conflict with Israel.”

Mbuyiseni Ndlozi, national spokesperson for the Economic Freedom Fighters party and one of the leaders of the organization BDS South Africa, hailed the decision as “by far the most authoritative endorsement of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) against Israel campaign.”

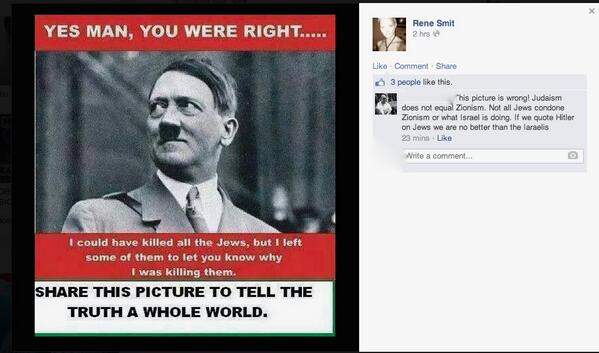

Jessie Duarte, the deputy secretary-general of the ANC, issued a statement in 2014 to reaffirm the party’s stance during Operation Protective Edge. In her statement, Duarte wrote that Israel “has turned the occupied territories of Palestine into permanent death camps…. for the State of Israel, the notion of an eye for an eye has become perpetual massacre with merciless revenge which has lasted for more than 60 years”—a clear reference to the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, and not simply its capture of Arab-controlled territories during the 1967 war, as the root cause of the conflict, Rene Smit, the social media manager of the Western Cape ANC branch, took this sentiment even further with a Twitter post featuring a openly anti-Semitic meme in which Hitler is pictured with the caption “Yes man, you were right. I could have killed all the Jews, but I left some of them to let you know why I was killing them.” The ANC did not denounce Duarte or Smit’s actions.

The precipitous growth of the BDS movement in South Africa began with Thabo Mbeki’s presidency, from 1999 to 2008, and stemmed from his unusual fascination with the Arab-Israeli conflict, as chronicled by RW Johnson in the book Will South Africa Survive? Mbeki’s belief was that now that South Africa had been liberated from apartheid, the natural next step was to free the Palestinians from Zionism—caricatured as a colonial movement dispossessing and expropriating the native population. In South Africa, Mbeki saw with his own eyes an oppressive white minority regime—just ten percent of the total population—which had imposed itself upon a non-white majority, creating in the process an oppressive class-system that had to be overthrown. Mbeki likened the Palestinian struggle to the South African experience on several occasions, such as his opening remarks at the United Nations African Meeting in Support of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People in 2004, and at an Al-Jazeera forum in 2010. As chronicled in RW Johnson’s book How Long will South Africa Survive?, the Mbeki administration saw the necessity of using the same methods against “Apartheid Israel” as had been used against the Boers in order to achieve the same result. Boycotts, divestment, and sanctions were those methods, and Jews (cast in the role of whites) handing over power to the rightful owners of the land (Palestinians, cast in the role of blacks) was the intended outcome.

President Mbeki would invite Israeli and Palestinian representatives to his cabinet to debate the issue, but the Israelis, such as Yossi Beilin and Avraham Burg, came exclusively from the far-Left. Through these talks, Mbeki became more heavily entrenched in the idea that Israel was an apartheid state and that the role of the ANC was to support its Palestinian brethren in their struggle for liberation.

South African President Thabo Mbeki speaks at the 2008 World Economic Forum on Africa. Photo: Eric Miller / World Economic Forum / flickr

In 2001, Mbeki’s government hosted the first United Nations World Conference against Racism, Xenophobia, and Other Forms of Intolerance in the western city of Durban. The conference, subsequently known as “Durban I” as it inaugurated a series of follow-up meetings, was held a few days before the 9/11 atrocities. While it was supposed to tackle racism and human rights violations across the world, the conference, and particularly its parallel gathering of NGOs, quickly turned into an anti-Semitic hate-fest that sent shockwaves through much of the Western world. The conference condemned Israel as being the most racist country in the world while completely ignoring the atrocities taking place not only in the Middle East but also on the very continent on which they stood as they made their venomous denunciations of Israel.

Representatives from the United States, Canada, and Israel walked out of the conference and condemned it for displaying and expressing open anti-Semitism, as well as using the forum’s important platform to focus opprobrium solely on the democratic state of Israel.

Since then, anti-Israel sentiment has become a staple of South African politics, justified in the name of racial struggle and social justice. The South African BDS movement has made headlines across the world for its aggressive tactics, including the University of Johannesburg’s academic boycott of Ben-Gurion University, the South African Artists Against Apartheid cultural boycott campaign, and the annual Israel Apartheid Week. Woolworths department store is facing a massive boycott campaign due to its decision to sell Israeli produce, despite the fact that none of its imported produce comes from the West Bank. Last year, BDS activists “protested Israel” by entering a Woolworths supermarket in Cape Town and putting a pig’s head in the kosher section of the store. A leader of the Congress of South African Students, which organized the protest, said that the organization “will not allow people who will not eat pork to pretend that they are eating clean meat, when it is sold by hands dripping with the blood of Palestinian children.”

Indeed, anti-Israel activism blurring into anti-Semitism is especially pronounced on campuses. In February, the Student Representative Council at Durban University of Technology called on the school to expel all Jews unless they denounce Israel. Three months later, the student council president at the University of the Witwatersrand (popularly known as “Wits”) posted a message on Facebook saying “I love Adolf Hitler.”

An anti-Israel activist places a pig’s head in the kosher section of a Cape Town supermarket. Photo: Twitter

In 2013, members of BDS South Africa stormed a concert at Wits featuring the Israeli jazz saxophonist Daniel Zamir. While the activists claimed it was an “anti-Zionist” action, some of its participants began chanting the slogan “Shoot the Jew” (“Dubula e Juda” in Zulu), based on a protest song sung in the 1980s against the white oppressors of the apartheid regime. When questioned, Muhammed Desai, coordinator of the protest and the head of BDS South Africa, said the protesters did not mean the slogan literally.

“Just as you would say ‘Kill the Boer’ at a funeral in the ’80s, it wasn’t about killing white people, it was used as a way of expressing opposition to the apartheid regime,” he said, adding that “the whole idea [of] anti-Semitism is blown out of proportion.”

One of the people storming the stage that day was Klaas Mogkomole, a 24-year-old student who was born and raised in the township of Soweto. Klaas was began his ANC career at an early age, climbing the ladder within the youth movement, becoming treasurer of the ANC youth league and then the head of the Wits Branch of the South African Student Congress before he reached the age of 20. As a consequence of the affirmative-action laws enacted after the dismantling of apartheid legislation in 1994, the ANC has a heavy presence on South African college campuses. Within it, the BDS movement has found a major strategic ally in its campaign against Israel, supplying “training and information” to the youth leaders as soon as they enter the scene.

This is what happened to Klaas. When running for office for the Student Representative Council at Wits University, the BDS charter was given to him as part of his training, reinforcing the narrative of how Israel practices apartheid and is stealing land from the Palestinians. Having grown up with the struggle against apartheid, and feeling the consequences upon his own life, Klaas was outraged by the idea that while it had been abolished in his own country, apartheid was being enacted somewhere else. Eagerly egged on by BDS activists, he vowed to fight for what he thought was a just cause.

Klaas tells me that in order to make sense of how he became a part of the BDS movement, I need to understand what it does to a black South African when someone mentions apartheid and the kind of emotions that evokes. These are the buttons that BDS leaders push, using the South African anti-apartheid struggle to promote their own agenda. So strong is their presence on campuses that involvement in youth politics or campus activities means involvement with, and adopting the ideas of, BDS. That’s what happened to Klaas Mogkomole. He was brought into it, didn’t really question it, and as a socially conscious person who has lived through apartheid, he naturally felt compelled to fight it wherever it reared its ugly head.

In 2013, during Israel Apartheid Week, the leaders of BDS South Africa informed the group now known as the “Wits 11” that there was an Israeli saxophone player coming to perform at the campus. They were told that this was unacceptable and needed to be stopped. Klaas and his comrades disrupted the concert. “I really felt I was doing something important,” he told me. “That word is the trigger. Saying ‘apartheid’ to me is like mentioning slavery to an African-American. It demands action, so I acted.”

Earlier this year, 16 high-ranking members of young ANC-affiliated student, political, and business bodies, including Klaas, went to Israel on a fact-finding tour hosted by the South Africa Israel Forum, the South African Jewish Board of Deputies, and the South African Zionist Federation. For the past few years, these organizations have organized trips to Israel to combat the growing anti-Zionist sentiment in South Africa and to inform the young future leaders of the country of what Israel is and is not. The participants were taken to destinations from Hebron to Tel Aviv, speaking to representatives from the political Left and Right, Israelis as well as Palestinians, and encouraged to ask whatever questions they needed to form their own opinions.

As the youth leaders made public their plans to go on the Israel trip, BDS South Africa offered them 40,000 rand ($3,200) to publicly decline the invitation. When they all insisted on going, the participants were vilified on social media and threatened with ouster from the ANC. They went anyway, and what they saw came to change their minds, and lives, forever.

When I got to Israel, I spent a lot of time walking around; trying to engage with the communities we visited. At this point I was still convinced, still an avid BDS-er, but I had a hard time finding anyone who had even heard of BDS, much less cared about its existence. The BDS had had told me that it was doing great work for the people in occupied territories, but once I got there people on the ground couldn’t even tell me what they do or what they are.

What they did tell Klaas was something he had never read in the colorful pamphlets or been told at the propaganda meetings: Everyone, Jews and Arabs alike, said that they wanted peace, a two-state solution, and an end to the conflict so that they could live their lives. BDS advocates had never told him that, nor had they worked to achieve that two-state solution—so how could BDS South Africa say they represent the people in these territories?

“For as long as I can remember, Nelson Mandela has been my role model,” Klaas said.

Not only when it comes to politics, but also as a model for character and bravery in life, and going on the trip to Israel to see it for myself, even after all that pressure, was inspired by Mandela and his insistence on doing right even when it came at a considerable cost. After being on this trip I am neither pro-Israel, nor pro-Palestine, but pro-peace, just as Nelson Mandela was. Mandela wanted a two-state solution and he always emphasized that Israel needs to be recognized as a Jewish state. This was his position, and it is also mine.

The BDS movement has latched on to the ANC, using the dark history of South African apartheid to smear Israel, much as the Soviets and their allies did during the mid-1970s, when the UN General Assembly passed its infamous resolution linking Zionism with South African apartheid and deeming it “a form of racism and racial discrimination.” The method has been very effective, making the South African wing of the global BDS movement not only the most active, but also the most aggressive in tactics and tone.

I wanted to ask Klaas about the fact that he as a black man has been used as a pawn and an alibi, but something stopped me. It was a discomfort, or maybe just that sense of not knowing exactly how to express myself on this point. And I guess that could be at the heart of it, the key to the cynicism with which the BDS movement operates. They know that a black South African saying “apartheid” holds so much power and significance, so they shamelessly use that pawn in a game they play to win.

Even though the trips to Israel have proved successful, the problem in South Africa of anti-Semitism couched in the language of anti-Zionism is broader and wider than anything a 16-person visit to Israel can resolve. The ANC is the product of a horrendous chapter in Africa’s history, and the movement came to power through popular agitation and wise, peaceable leadership. But in the 21 years that elapsed since the death of apartheid, the government of South Africa has proven to be corrupt and weakened without an obvious enemy and an inspiring political fight. Israel has provided both those things.

One might say that the ANC and BDS South Africa are in business together, and it is a business, as both need to highlight apartheid in order to justify their existence and their actions to the outside world. When young leaders chose to go to Israel to learn more, and to educate themselves about the conflict, they were vilified and threatened, losing their place in line for the ANC leadership. The ANC and the BDS movement are not acting as mediators, but rather as parties to the conflict. If the Arab-Israeli conflict ends, the activists will not get paid or get attention, so by pursuing a line of no compromise, the BDS movement ensures that it will never happen. Young black South Africans, those who should be the future of the country, are being used to preserve the status quo rather than build a better future, once again they paying the price for a dishonest system.

As we part ways, I asked Klaas what he thinks of the relationship between Israel and South Africa going forward. He told me that the ANC and South Africa could and should play a role in the peace process.

We have a unique experience of struggle, peace, and reconciliation in this country, and I would love for that experience to be used to bring peace in the Middle East. What we did here was force ourselves to let go of the past and start from a new page, only looking at what would benefit our grandchildren, rather than lingering on our painful past.

Klaas’ vision for South Africa and Israel is heartwarming, but choosing to go to Israel has seriously jeopardized his future in the ANC. Klaas told me again that he does not want to take sides, adding that once you take sides you cannot be a neutral part of a compromise. But judging by recent reports, the ANC has chosen a side, and is fiercely sticking to it. The ANC recently announced its plan to cancel the country’s dual citizenship policy in a bid to prevent South African Jews from making aliyah and serving in the IDF.

Klaas chose to do the right thing, and he is paying the price, along with the 15 others who stood beside him. The BDS movement used his painful past to further their agenda, causing him to lose the future he once dreamed of in the process.

![]()

Banner Photo: Meraj Chhaya / flickr