Unpopular, undeterred, undefeatable. Master of the political machine. And soon to be Israel’s longest-serving prime minister. As Benjamin Netanyahu begins his fourth term, a look forward at his possible legacy.

We went to bed with Peres and woke up with Bibi, Israelis said of the 1996 elections, in which the young Benjamin Netanyahu eked out an upset victory over Shimon Peres. This time it happened again. We went to bed with what looked like a tie, which was surprising enough, and woke up with Bibi.

To say that this was unexpected is an understatement. “Nobody knows anything,” a friend of mine said in the Tel Aviv pub where we watched the exit polls come in. There seemed to be myriad possibilities, everything from a slim Center-Left coalition to a national unity government. But the next morning, we did know, and more decisively than ever before. The Likud party was six seats ahead of its rival, the Zionist Union, and guaranteed to form the next government.

I live, I freely admit, in the Tel Aviv bubble, where Netanyahu is, to say the least, unpopular, but none of us could be blamed for being shocked. Every poll taken before the vote indicated that Netanyahu was more or less finished, soon to be sent home by an electorate that had grown tired of him and genuinely desired a change in leadership. Instead, we found ourselves facing the fact that Netanyahu had not eked out a victory, but soundly thrashed his opponents, returning to office with a genuine mandate and more political capital than ever before.

Whether you think this is a good thing or not depends on your point of view. Certainly, the Obama administration has made its opinion on the matter quite clear. But however one views the outcome, there is no question that Netanyahu has now emerged as the dominant political figure of his generation, and the expression “Bibi, king of Israel” is no longer simple hyperbole.

Netanyahu arouses strong emotions in both his supporters and detractors, but it is impossible to argue with his success. If he survives for another full term, Netanyahu will become Israel’s longest-serving prime minister in 2018. And even if he does not, he has won three elections in a row, this time with a decisive margin that places him well ahead of even his most powerful rivals, no mean feat in the inherently unstable world of Israeli politics.

This is all the more remarkable because, in Israel itself, Netanyahu is not overly loved, nor even particularly popular. He is adored in certain circles on the Right, and certainly by American conservatives, but I cannot count the number of times Israelis have told me that they voted for him because “Who else is there?” Indeed, even when he has been personally unpopular, Israeli voters have consistently cited Netanyahu as the man most fit to be prime minister.

This contradiction can be seen quite clearly in the election results. Though his margin of victory was larger than ever before, it appears to have come almost entirely from those already committed to the Israeli Right. The poor showing of Israel’s smaller Right-wing parties bears this out. It seems that, fearful of a Center-Left victory, those who would normally have voted for Jewish Home or Yisrael Beiteinu bolted for the Likud, giving Netanyahu his lopsided victory. The Right itself is well aware of this. Indeed, in his post-election speech, Jewish Home leader Naftali Bennett essentially thanked his voters for not voting for him. Netanyahu, in short, dominated the Right, but failed to achieve the national consensus that has consistently eluded him. They may vote for Netanyahu, but Israelis by and large remain ambivalent about him.

Part of the reason for this is simple aesthetics. In terms of image, Netanyahu, with his telegenic looks and aptitude for the art of spin, is a far more American-style politician than most of his predecessors. For the most part, Israelis tend to prefer leaders who are a bit rumpled in style. Yitzhak Rabin, for example, was famously unable to tie his own tie. Netanyahu looks like he was born into his.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu speaks at a memorial service for the late prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, held at Mount Herzl cemetery in Jerusalem, marking the 17th anniversary of Rabin’s assassination, October 28, 2012. Photo: Kobi Gideon / Government Press Office / Flash90

In and of itself, this would not be much of a problem, but Netanyahu’s assiduously crafted image helps create the impression that he is, ultimately, a cynical politician rather than a statesman. His much-derided rejection of a Palestinian state on election eve, followed by his swift backtracking, is a classic example. Which is the real Bibi? How much of what he says comes from political expediency, how much from genuine conviction? Does he really mean anything he says? As one Left-wing Israeli told me, “The first thing you have to remember is that Bibi is a liar,” a sentiment that was famously echoed by President Obama and then-French President Nicholas Sarkozy, and likely in numerous foreign capitals. Even many on the Right quietly agree with this impression.

At the same time, however, what many seem like Netanyahu’s cynicism has served him—and Israel—well on numerous occasions. If he is anything, he is a master politician; a chessmaster of the highest level, as his come-from-behind victory last month proved beyond a shadow of a doubt. Faced with fading poll numbers, socioeconomic discontent, and a general sense of “Bibi fatigue,” the prime minister brought all his talents to bear at the last minute and prevailed. He did do it, in part, through scare tactics, as well as his now-regretted rejection of a Palestinian state and some indefensible remarks about Israeli-Arab voters, for which he has since apologized. But scare tactics are an ancient method of political persuasion, and few politicians have refrained from them should they prove useful.

Indeed, there is often a sense that, whether one loves or hates him, Netanyahu tends to get a raw deal. He is often derided and demonized by those who, in the end, are not much different from him. The universally beloved Shimon Peres, for example, was once referred to as “an inveterate schemer” by none other than Yitzhak Rabin himself. Even his latest victory was achieved by methods not dissimilar to those used by President Obama to win a second term: Go negative on your opponents, and do everything possible to pump up one’s electoral base. Yet Netanyahu is, for some reason, held to a different and, in some ways, impossible standard.

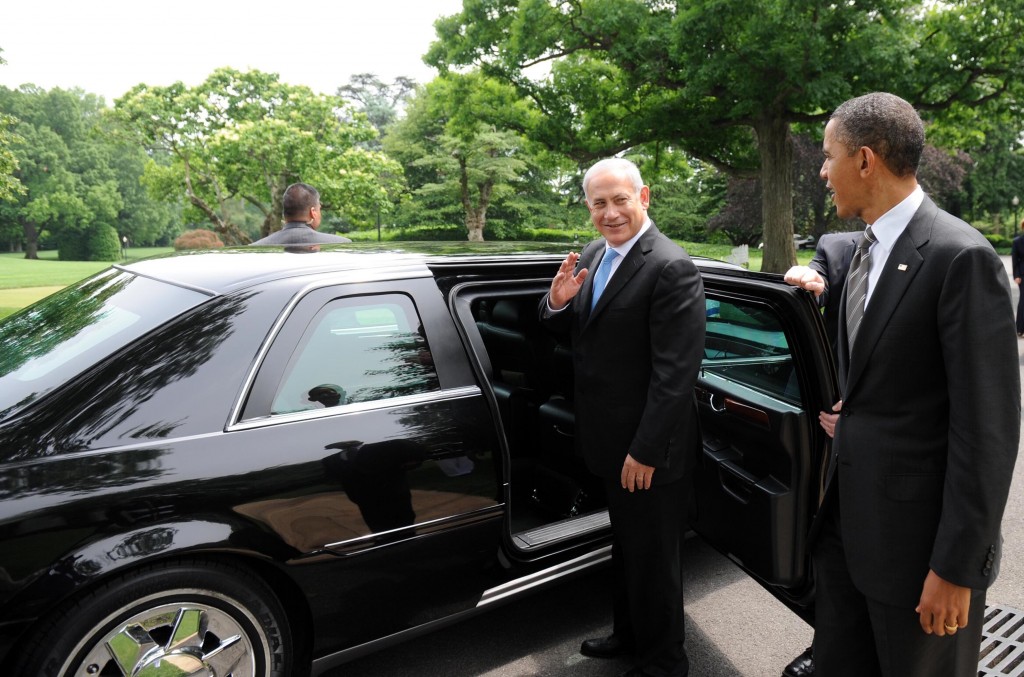

U.S. President Barack Obama talks with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu while walking from the Oval Office to the South Lawn Drive of the White House, after their meeting on May 20, 2011. Photo: Avi Ohayon / Government Press Office / Flash90

Netanyahu has also benefited from what his opponents find most distasteful: His relatively bleak view of the possibility of peace with the Palestinians. Whatever his real thoughts may be on a Palestinian state, Netanyahu was an early critic of the Oslo process, which ultimately collapsed into the second intifada. He was equally critical of the disengagement from Gaza, which resulted in continuing missile attacks on Israeli civilians and a series of ever more intense military operations. Whatever Israelis think of such policies, it is difficult for them to deny that Netanyahu was at least partially correct each time.

Nor can it be said that his tenure has been without success. Despite widespread discontent with the rising cost of living and economic inequality, Israel’s macroeconomic numbers are excellent. According to the U.N., its nominal GDP is higher than countries like Finland, Greece, New Zealand, and Ireland; while the International Monetary Fund places its per capita GDP higher than that of Spain, Russia, and India. At the same time, Netanyahu has maintained a fairly measured and careful security policy that, until last summer’s Gaza war, kept things relatively quiet. Nonetheless, it often seems as if his opponents are determined to deny him credit for any of this. Clearly, something about Netanyahu hits a raw nerve.

This attitude was perhaps most eloquently expressed by Israeli writer Ari Shavit as far back as 1997. “When all is said and done,” he wrote,

The truth is that we hate Benjamin Netanyahu so much because the hatred makes life easier for us. Because this hatred responds to our deepest emotional needs. Because hatred of Netanyahu saves us from having to deal with our own internal contradictions and errors. And because hatred of Netanyahu enables us to conveniently forget that before the bubble burst, we had acted like fools.

Indeed, perhaps Netanyahu drives his opponents mad precisely because of this: He has come to be associated with sometimes unpopular but often correct assessments of Israel’s security situation; and while his economic policies have resulted in general discontent, it cannot be denied that they have contributed mightily to Israel’s ability to stay economically afloat in an era of economic crisis and collapse. Even if only unconsciously, many Israelis associate Netanyahu with the possibility of at least temporary prosperity and security, something that, in a region like the Middle East, cannot be easily dismissed. Perhaps Netanyahu’s most fervent critics hate him precisely because they suspect he may have been right all along.

Or perhaps it is simply because Netanyahu is such a skilled and seemingly invulnerable survivor. Despite all the best efforts of his opponents, he refuses to be toppled. Love him or hate him, he is still there. The Israeli political system has devoured leaders as powerful as David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir, yet Netanyahu has survived. It is impossible to disregard any politician capable of such a feat. In this sense, Netanyahu’s cynicism has served him well.

It would be a mistake, however, to dismiss or deride Netanyahu as just another cynical politician. His tactics may be cynical, perhaps more cynical than necessary at times, but the man himself is not. There is another side, the other face, of Netanyahu, which is that of an unabashed and passionate idealist.

In many ways, this idealism is an inheritance. His father, the universally respected historian Ben-Zion Netanyahu, was a stalwart of Right-wing Revisionist Zionism; while his brother Yonatan famously gave his life to rescue Israeli hostages in the now-legendary 1976 Entebbe Raid. When Netanyahu speaks of the Jewish state and his dedication to its safety and security, he is not simply playing politics. It is fair to say that he really means it, and his opponents are wrong to claim otherwise.

The strongest proof of this is his consistency on security issues. He has been speaking out for years on the issue of Iran’s nuclear program, for example, whether elections were pending or not, and his position has not shifted in the slightest. He was one of the first world leaders to speak out on the Iranian nuclear issue, and from the UN to, controversially, the U.S. Congress, he has asserted that anything short of a deal that completely dismantles Iran’s nuclear infrastructure represents an existential threat to the Jewish state and, indeed, the world. In fact, it is not entirely an exaggeration to suggest that the enactment of consistently tougher sanctions on Iran is partially the result of both Netanyahu’s activism on the subject and the implicit threat that he might order a military strike if the issue is not resolved in a manner that ensures Israel’s security.

His critics tend to disregard all of this this in favor of charging him with engaging in cheap and manipulative tactics. Indeed, Netanyahu’s recent speech to Congress was widely attacked as mere electioneering. But this is highly unlikely. Netanyahu paid, and is still paying, a steep political price for it. The man appears to genuinely believe—and rightfully so—that a nuclear Iran is an existential threat to Israel, and acts accordingly.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu speaks before a joint session of Congress for the third time, March 3, 2015. Photo: Heather Reed / flickr

As mentioned above, Netanyahu has, for the most part, been equally consistent on the peace process. At the time the Oslo accords were signed, he called them a “historic blunder” that would only lead to further violence. Later, he warned that the disengagement from Gaza would result in a Hamas takeover and, again, further violence. He has been, for the most part, vindicated on both points, something that contributed mightily to his first victory in 1996 and his return to office in 2009.

Netanyahu’s numerous clashes with President Obama seem to stem from the same considerations. Whether one agrees with him or not, Netanyahu likely considers the concessions to the Palestinians that Obama has demanded as a genuine threat to Israeli security, and his defense in regard to his supposed rejection of a Palestinian state—that it would be inadvisable in a Middle East that is tearing itself apart—was likely sincere as well.

And it is this sincerity that makes him such a strange and contradictory figure, a bizarre synthesis of cynicism and idealism. At his best, he makes use of his cynicism in the service of his ideals. For the most part, he has succeeded. Indeed, in every confrontation with his domestic and foreign critics—including the Obama administration—he has emerged victorious.

Yet it is possible that, despite his convictions and his unquestionable political skill, Netanyahu may ultimately prove to be a tragic figure. His brinkmanship is high risk, and has come at a high price. The Obama administration’s intense criticism of him following his reelection, including a reportedly contentious phone call that was less congratulatory than hostile, may threaten Israel’s most precious strategic asset. And while his victory was decisive, the Center-Left opposition nonetheless emerged stronger than it has in years. It is entirely possible that, unable to resolve his own inner contradictions, Netanyahu may win every battle and lose the war.

And this may also threaten Netanyahu’s only unrealized ambition. An admirer of leaders like Winston Churchill, Netanyahu clearly wishes, on some level, to be a great man; to emerge from his tenure as a historical figure; someone who, in short, has changed the world, hopefully for the better. Netanyahu is a man of strong beliefs, and possesses the political brilliance to back them up. But throughout his relatively long tenure, the politician has tended to hold back the possibility of the statesman.

Whether Netanyahu will ultimately be able to overcome this remains an open question. Certainly, in regard to his two most prominent opportunities to do so—the Iranian nuclear issue and the peace process—success seems more remote than ever. To be king of Israel is by no means an entirely glorious task. Israel’s kings by and large came to bad ends, and this has often been true of the modern State of Israel’s prime ministers as well. Nonetheless, Netanyahu now has an unprecedented chance to change this; to prove that he does indeed have greatness in him. The question is whether the cynic will allow the idealist to achieve it.

![]()

Banner Photo: Flash90