What will the Holocaust mean after all of the survivors are gone?

If it is in any way possible for genocide to have had a heyday, the Holocaust surely once had such a moment in time. The world’s greatest mass murder, which for decades had succumbed to the shrill sounds of global silence—in part due to shock, and the rest to embarrassment—“enjoyed” a period when it was the atrocity du jour, the anthem to man’s inhumanity to man. This period began toward the end of the 1970s (exemplified by the hit 1978 miniseries Holocaust) and reached its zenith by the mid-1990s. During that improbable time, the Holocaust had bizarrely become a cultural touchstone fashioned from the ashes of Auschwitz.

Yes, you read that right: A Jewish genocide was once in vogue, and it was not a passing trend. It had cultural staying power—with all the cache that inevitably turned it into a cliché. The Holocaust was hip. Cattle cars and tattooed forearms found their way into cocktail conversations. Knowing something about the Holocaust—almost anything—was a litmus test for entry into polite company, even though the material itself was impolitic, wholly alien, and had no place in any social circle.

The Holocaust doubled as both the era’s clarion call and siren song, bringing out a schizophrenia in societal norms that continues to bedevil our current age. After all, reflecting upon an atrocity too long tends to normalize it; pretending to have figured it all out trivializes it; subjecting it to all sorts of cultural and artistic representations may end up distorting it beyond recognition. The shameless voyeurism that accompanied the study of the Holocaust would become the big bang that led to the presumptions of reality TV and even, perhaps, to Donald Trump’s White House ascendency. Nothing was deemed private, everything was declared knowable. Hubris, an artifact of the ancient Greeks, had risen to an art form in the postwar West.

The Holocaust was framed as a freak accident of history that was made to look presentable so it could be viewed in public—a taboo subject now out in the open. An atrocity was suddenly democratized. Everyone should see it; everyone should know it; and once that happens, everyone can claim proprietary ownership of it. Yet, if the Holocaust was truly unimaginable, ineffable and unknowable—as so many had claimed it to be—then it should have resisted all efforts to expose it to too much light. Awe and humility should have shielded the Holocaust from pop cultural poking. After all, this was somber material, not necessarily for everyone, metaphorically not subject to a Freedom of Information request. At the very least, its uniqueness should have rendered it beyond the capacity of those who would dare to re-imagine or purport to comprehend it.

And so for roughly twenty years, in an otherwise divisive and fractious world, there was at least one cultural consensus: Nazis were evil beyond measure, and the Holocaust was unspeakably horrible. Yet, paradoxically, everyone believed they had an obligation to speak about it, to offer an opinion, to profess an expertise, to register the appropriate levels of disgust and pity, and then say, by way of benediction, “Never Again.”

Silence became the one thing the Holocaust demanded, and yet the world had little interest in shutting up. In the information age that eventually replaced mainstream media with the self-empowerment of the Internet, knowledge was immediate, varying and debatable, and absolutely nothing was entitled to be left alone. If it could be Googled, then it was open for business—regardless of how presumptuous and dirty that business would turn out to be.

Without warning, the unimaginable had vaulted over the unfathomable and was anointed as newly accessible. The ineffable now had a common language. Once sacred symbols were transformed into kitsch. False analogies emerged as the new ethic; desecration was the forerunner to today’s disruption—and piety be damned! The Holocaust, which had been the exclusive trademark of Jewish suffering, became universalized, easily adaptable to anyone’s misery. Anne Frank was the template teenager who suffered through a difficult emotional time. Thank God she had a diary.

Rogue (even law-abiding) cops were referred to as Gestapo. Anorexic models were marketed as the “Auschwitz chic.” AIDS was the Holocaust of gay men; the fur and leather trade was the Holocaust of the animal kingdom. The Shoah became a misapplied proxy for all manner of human calamity—everyone possessed it, and everyone would get a chance to personalize it, like a library book always available and renewable at the circulation desk. But if the Holocaust was everywhere, then it was nowhere; if it could be universally experienced, then it had no particular meaning and possessed no unique moral properties.

Modesty was certainly nowhere to be found. Jews themselves weren’t sure whether all this Holocaust hoopla was a badge of honor, or a pernicious fashion statement: the yellow armband and tailored patch redux—without the walled-off ghettos and death marches. Here was the perfect example of a well-meaning world once again killing Jews—this time with kindness, the trivialization of historical truth and the desecration of memory. The misappropriation of the Holocaust was an offense to the moral universe, and to the six million dead.

From the early 1990s through a few short years after 9/11, annual Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Remembrance) commemorations were held in thousands of synagogues and Jewish Community Centers around the world. Many Christian institutions and universities honored the day, too. City councils across America, and even the House of Representatives, passed resolutions marking the genocide of the Jewish people as a black day in world history. The study of the Holocaust was added to the curriculum of middle and high schools, as a civics lesson on the fall of civilization. Endowed chairs in Holocaust studies, and classes in Holocaust literature, were added at both public and private universities. Trips to Auschwitz were organized. A March of the Living crossed paths with millions of ghosts trying to head in an altogether different direction.

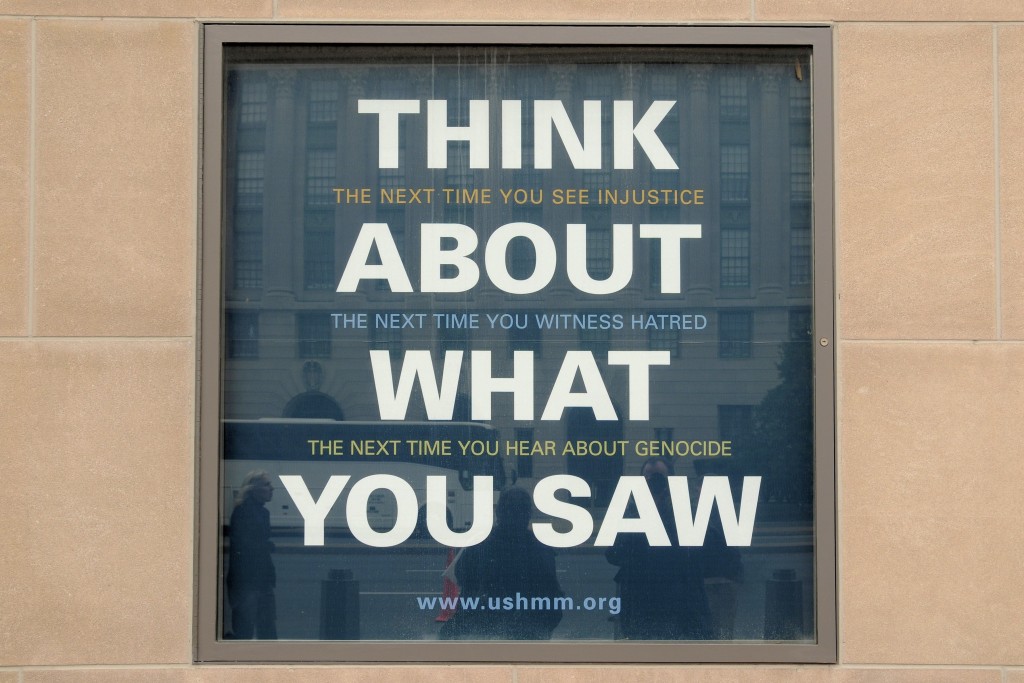

The Holocaust Memorial Museum opened in Washington, D.C. in 1993, and soon became the biggest attraction within the Smithsonian family. There were month-long waiting lists to get a reservation. Visitors were each given a card with the name and a brief biography of someone who had perished in the Holocaust. Apparently, walking through the Museum while clutching a card somehow humanized the experience. Few seemed offended by such simulations. Yet, when guests left the museum, they were usually headed off to some other Smithsonian attraction, or to Dupont Circle for a late lunch. No such agreeable options awaited those whose names were written on those cards.

The grand statues of Lincoln and Jefferson no longer held much interest when compared with the artifacts and offerings of a museum dedicated to mass death. Hitler, Heydrich, and Himmler were the founding fathers of gas chambers and killing fields. In addition to making the murderers real, the instruments that were used in perpetrating the crimes where given prominent places of viewership. The museum even showcased an actual cattle car. One could walk through and…who knows what feelings such movements were intended to arouse? One thing was for certain: A fading Declaration of Independence surely could not keep pace with tantalizing spectacles such as these.

The success of family trips to the nation’s capital now depended on whether they were lucky enough to score tickets to the Holocaust Museum. The Disney Corporation, suffering from amusement park envy, took notes on how to manage the overflow crowds that awaited entry into a house of horrors unlike anything they could possibly offer in Anaheim or Orlando. Other museums attempted to outdo one another as curators of Holocaust art. Some became theaters of the absurd. The Jewish Museum of New York mounted an exhibit featuring Zyklon B canisters displayed as Chanel handbags and Auschwitz itself constructed out of LEGO.

A few months after the Holocaust Memorial Museum opened, Schindler’s List became a global box office phenomenon, spawning a foundation that videotaped the oral histories of tens of thousands of Holocaust survivors worldwide. The film oddly showcased two Nazis—one hopelessly beyond evil, the other redemptive—where the Jews were bit players and the rescue of 1,200 somehow overshadowed the wide scale moral failure that culminated in eleven million total dead. Not long after that, the sitcom Seinfeld built an entire episode around amorous lovers “making out” in the balcony of a theater while watching the movie—demonstrating that a film that ultimately became a sanctified household name could also take a joke. It got even worse. Another Seinfeld episode featured a disagreeable restaurateur who was labeled as the “Soup Nazi.”

Seinfeld co-creator Larry David went on to star in his own comedy series, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and proved that Nazis and the Holocaust may have been his obsession all along. In one episode, the term “survivor” became the butt of a joke when a Holocaust survivor was conflated with someone who endured a reality TV series of the same name. Both survivors squared off, absurdly comparing their relative sufferings. David was not done. In still another episode, a chef with numbers on his arm ended up being not a Holocaust survivor, but a lottery player who penned his ticket on his arm—suggesting that tattoos on forearms have many purposes, and that the Nazis had devised nothing special.

Such degenerate Holocaust art took on other forms. Mel Brooks set a record for Tony wins with his Broadway musical The Producers, in which Nazis were far too busy frolicking on stage to have time for a genocide. Near the end of the 2001 Tony ceremony, Brooks was noticeably exhausted from having taken the podium to claim his many prizes. After acknowledging everyone involved in the success of the musical, he finally thanked Hitler for being so funny.

Elie Wiesel’s Holocaust memoir Night became an Oprah Book Club selection in 2006. He toured the grounds of Auschwitz with Oprah Winfrey, and later escorted President Barack Obama and Chancellor Angela Merkel when they visited Buchenwald. (Sometime in between those visits, Wiesel narrowly escaped a kidnapping by a Holocaust denier in San Francisco.) Documentaries about the Holocaust flourished, seemingly taking home the Oscar each year, as if a tiny statue of a baldheaded man was a fitting honor for a film about the nakedness and depravity of humanity. History books, such as Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust, became international bestsellers—even as its finger of blame shifted onto those beyond card-carrying Nazis.

Actor-writer-director Roberto Benigni and his wife, co-star Nicoletta Braschi, at the premiere of Life is Beautiful at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival, where the film won the Grand Prix. Photo: Georges Biard / Wikimedia

Holocaust memoirs increasingly appeared on the pages of book reviews around the world. There were so many, in fact, a few charlatans snuck in, as well. Binjamin Wilkomirski fabricated an entire childhood in a death camp, despite not being Jewish and living nowhere near Poland when he was an infant during the war. Herman Rosenblat, an actual survivor, concocted a love story that was slated to become a feature film, until it was revealed that the kind of love he was describing was logistically impossible and had no place in a death camp.

The low point was the astounding critical and commercial success of the 1997 Italian film Life is Beautiful. Even its title was an appalling distortion: Beauty neither lived nor survived in such places of ineradicable evil. The Nazis were in the business of mass murder, whereas the film seemingly was set in a parallel universe where Jewish inmates had the luxury to walk freely, communicate to their relatives through the camp intercom, and manage to invent a game to amuse a child who apparently had no idea the grave danger they were all in. And to top it off, in answering his critics, the film’s director and star, Roberto Benigni, made a statement that, however he intended it, was far from benign: “We all own the Holocaust.”

Neo-Nazis, and skinheads with mostly empty heads, didn’t fare so well during this period. The historical event that they had insisted was pure fiction was now universally accepted as the darkest chapter in human history, the blackest hole in the moral universe, the genocide to end all genocides. The critical mass of Holocaust obsession had reached proportions too gargantuan to deny. It was now an atrocity of unqualified demonic dimension, seared into the world’s historical memory bank with the most unforgettable of fire.

And then, as quickly as it had ascended into the cultural consciousness, as improbably as it had inspired the artistic imagination, as definitively as it had reprimanded the world for its unsurpassable indifference, it just as quickly lost its moral mojo and soon faded as a cultural and moral touchstone. Yes, there were still movies being made, but far fewer and none that could compete with superheroes and mutants (ironically, X-Men was a Holocaust film, of sorts, with an opening scene set in a fictionalized Auschwitz). Far fewer books about the Holocaust were written, and rarely are they now reviewed in major publications. Social conversations turned to the war on terror—Islamist extremists are the new-look Nazis for the new millennium. A Holocaust fatigue set in, and with each passing year, the command that the mass murder of European Jewry once had on the world’s conscience lost its power to shame.

Yom HaShoah commemorations cooled to embers, and are less frequently held and more sparsely attended. The degrading of the Holocaust, which began the moment artists misappropriated its story and misapplied its message, gave way to something arguably worse—its irrelevance. No longer the banality of evil, the Western world’s fascination with the Holocaust begat the banality of overexposure. The result: We now live in a time when most people have heard of the Holocaust, but very few have absorbed its magnitude. It has fallen into the Trivial Pursuit dustbin of utterly superficial knowledge—a conga line of horror that includes the Inquisition and blood libels in the Pale of Settlement.

This was to be expected all along. Maybe the Holocaust was intended to be forbidden knowledge. Making it accessible also made it pornographic, nakedly vulnerable to crassness and indignity. Perhaps it should have been left to the piety of purists.

The interior of a boxcar at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Photo: Beth Jusino / Wikimedia

Meanwhile, the community of Holocaust survivors dwindled with each passing day. Obituaries continually noted one less witness to the handiwork of the Nazis and their collaborating henchmen. While the survivors walked the earth, they represented unimpeachable evidence of the crime. They were the living embodiment of the dead—their stand-ins and truth-tellers. But they also constituted a nightmare for Holocaust deniers who couldn’t so easily explain them away. When neo-Nazis decided to march in Skokie, Illinois in 1978, they did so precisely because Skokie had one of the highest concentrations of Holocaust survivors in the world. Goose-stepping into a hamlet filled with Holocaust survivors was a legal but spiritually lethal way for neo-Nazis to stamp out what otherwise could not be erased. They could not kill them, but they could further damage them—adding insult to the once injured.

Now, with so few survivors among us (and many left impoverished and neglected), and with fatigue already set in, the impulse to honor and commemorate continues to diminish. The Nazis knew all along that numbers are numbing. A single murder is a crime, millions murdered just a statistic—an insight attributed to yet another mass murderer. No matter how many cities hosted Yom HaShoah ceremonies, and no matter how many people attended, there would never be enough of them to light the sum total of six million candles.

What remains of Holocaust memory is now poisoned with even greater ill will and bad faith. Hijacked once again, in the same lifetime, by a sinister movement that trivializes and falsifies the Holocaust even further. On campuses, for example, Students for Justice in Palestine has disrupted Yom HaShoah commemorations, hosted events and rallies that equate Zionism with Nazism, charged Israelis with committing genocide against the Palestinian people, and proclaimed that Israel has turned Gaza into Auschwitz. On both sides of the Atlantic, such twisted, abhorrent thinking is fashionable on university campuses, despite the fact that many of SJP’s intersectional partners would be stoned, beheaded, or burned alive if they lived in Gaza. Israel, meanwhile, remains the only nation in the region that functions as a liberal democracy where an open, pluralistic society enjoys rights nowhere else seen in the Middle East.

In so many pernicious ways, this latest misappropriation, this vulgar corruption, is worse than conventional Holocaust denial. The existence of the Holocaust—the reality of its moral indictment of humanity—is not a difficult argument to win. Such claims were mercifully confined to crackpot conventions. They were in the same category as having to prove that there was once an African slave trade, or that the world is round. In such low-budget intellectual battles, the deniers revealed themselves to be nothing but barbarians and baboons.

When it comes to anti-Semitism cloaked in the smug smock of human rights, however, the toxic atmosphere against Zionism makes even the exploitation of the Holocaust fair game so long as it is being directed at delegitimizing the State of Israel—an especially favorite pastime of university and Leftist communities in the West. In such dizzying games of three-card monte, the Holocaust is not a myth, but an operating manual that Israelis are following, with great precision, in their “ethnic cleansing” of Palestinians. The fact that the Palestinian population has more than doubled since the Six-Day War becomes only an inconvenient and easily ignorable truth. After all, genocide requires subtraction in the census, not multiplication.

Memorial candles are lit during a Holocaust Remembrance Day ceremony at Naval Station Pearl Harbor. Photo: Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class James E. Foehl / U.S. Navy

Meanwhile, Iran continues to host its International Holocaust Cartoon Competition. But even here, the message seems to be that the relevance of the Holocaust is not in its moral lessons, or in its duty to the dead, but rather the multiplicity of ways in which it is being exploited by Jews, and Israelis, to manipulate world opinion, creating a false sympathy for the Jewish people, and a blank check for Israelis to harm Palestinians and deny them statehood. In such deviously cynical word games, the Holocaust is associated not with Jewish loss but with Israeli plunder—the self-justification of Israel to become the Nazi bully in the Middle East.

So appealing and inexorably long lasting is anti-Semitism that it can all too easily reconstitute itself into a vile movement where the Holocaust becomes not a tragedy but a weapon against Jewish continuity and the very existence of the Jewish state.

The Holocaust is dead. Long live the Holocaust.

![]()

Banner Photo: Daniel Foster / flickr