The Jewish state was uniquely situated to become the world’s most vegan country. A viral video was the tipping point.

When Ori Shavit went on a date with a vegan five years ago, she thought nothing would come of it. As a professional food critic, she didn’t think she could be with anyone who gave up so much of it. Curious, she asked her date why he was a vegan, and discovered that despite her position as a food journalist, she knew little about where the food she was eating actually came from. Something did come of that date: Shavit was inspired to learn more about veganism and eventually became a vegan herself. Because there was so little vegan cuisine at the time, she could no longer be a food critic, so she quit her job.

“Five years ago, there was almost nothing to write about, no [vegan] restaurants in Israel,” Shavit recalled. Today, it is the opposite and Shavit is no longer alone in her switch. Over the past few years, Israel has been swept by a vegan revolution. It is now the most vegan country on Earth, with a full five percent of its population eschewing all animal products. That number has more than doubled since 2010, when only 2.6 percent of Israelis were either vegan or vegetarian.

Vegans in Israel are both widespread and well-fed. There are over 400 “vegan-friendly” restaurants, including Domino’s, which sells a vegan pizza made with soy cheese exclusively in Israel. The world’s biggest vegan festival was held in Tel Aviv in 2014, which boasted 15,000 attendees. Even the Israeli Defense Forces have gone vegan, offering animal-free food, boots, and berets to vegan soldiers.

There is also not just one veganism in Israel; many have adapted it to their own lifestyles. There are Facebook groups: “Vegays” for vegan gays in Israel, and “vegan teenagers,” which consists of adolescent vegans attempting to get more meatless options in cafeterias.

Vegan activism also comes in many forms. Shavit now has a vegan food blog and hosts lectures on veganism, in which she talks about how veganism affects animal welfare, health, the environment, world hunger, and cuisine. Israeli Arab and Jewish vegans marched together in Haifa last year to protest for animal rights. Some activism is more intense: The advocacy group 269Life, which took its name from the number that was branded on a bull they rescued, have held demonstrations in which activists branded themselves with the number 269 using a hot iron to demonstrate the cruelty of branding cows.

But what caused this societal transformation? In the land of milk and honey, why are so many Israelis abstaining from both?

Shavit gives credit to two phenomena that occurred simultaneously: a rise in vegan activism, and a change in Israeli cuisine.

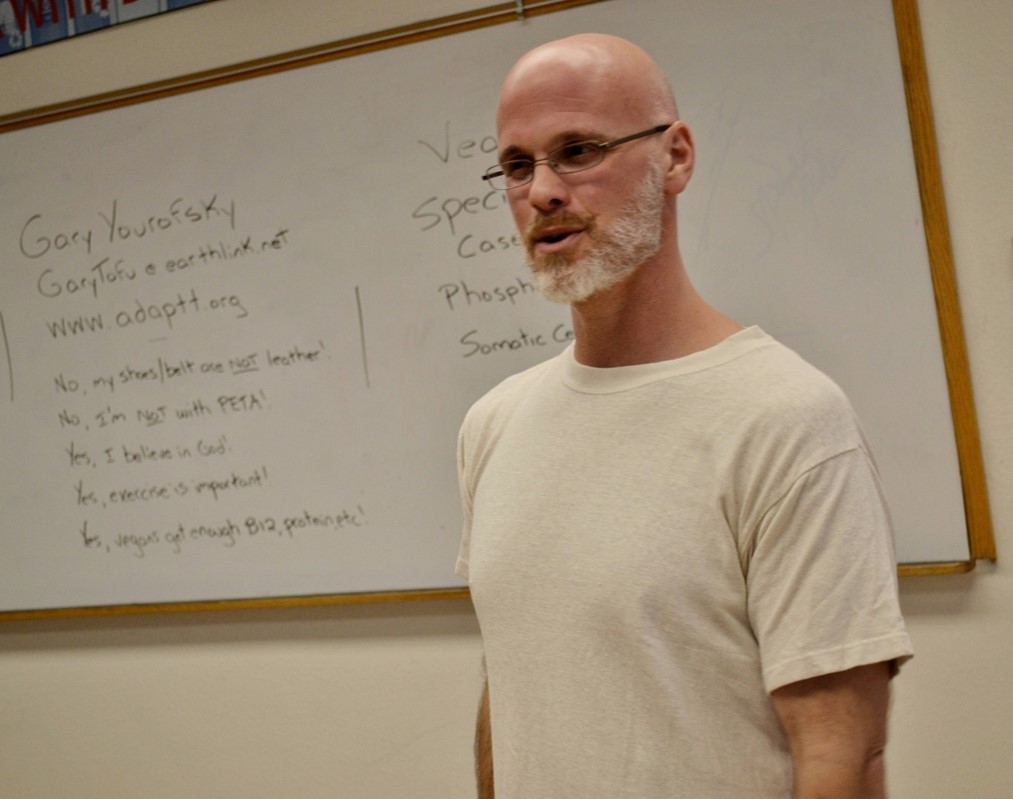

Much of Israeli vegan culture was sparked by one man: Gary Yourofsky, a bald, muscular, Jewish-American activist in his mid-forties. He wears glasses, has a tattoo on his right arm, and, according to his website, has been arrested 13 times and kicked out of five countries for “random acts of kindness and compassion.” A video of his lecture at Georgia Tech went viral in Israel after Hebrew subtitles were added to it. In the video, he talked about how discriminating against animals just because they’re animals is like discriminating against people based on race, religion, or gender. He also illustrated the inhumane conditions animals face in slaughterhouses. “Inside, these innocent, living beings are hanged upside down fully conscious,” he said. “They go in alive, against their will, and come out chopped up into hundreds of pieces.” He calls the way animals are treated a “holocaust” and refers to slaughterhouses as “concentration camps” because of the mass killing of innocents that occur within them. He also tried to make his audience empathize with animals. “How would you feel if the day that you were born, somebody else had already planned the day of your execution? That’s what it’s like to be a cow, a pig, a chicken, or a turkey on this planet,” he said.

The Hebrew version of the video has over a million views. Taken as a rough estimate of how many Israelis have seen the video (some of the views may be from other countries or may be the same person viewing the video multiple times, but many people in Israel may have watched the video together), this would mean Yourofsky has reached one-eighth of Israel’s population. “You always need a match to light a fire, and I think that match was that talk,” Shavit said. She added that Yourofsky’s lecture led to a shift in motivations for going vegan. Prior to the video, Israeli vegans made the switch for health reasons. The current vegan revolution, however, is about animal welfare.

Other activists have had an impact as well. The winner of the 2014 season of the popular reality show Big Brother was Tal Gilboa, who frequently spoke passionately about veganism. A survey later found that 60 percent of Big Brother viewers were considering changing their eating habits as a result.

Shavit also pointed out the growing awareness of veganism among leaders in Israel’s dining industry. “People like me started to really promote vegan culinary and vegan food in different ways,” she recounted. “I started having vegan nights at some of the best restaurants in Israel. We had dinners with the best chefs that changed their cuisine for one day to 100 percent vegan.” Chefs began to realize that they wouldn’t have to sacrifice the quality of their cuisine by going vegan, and diners realized that they could easily ask chefs for vegan food.

Still, Yourofsky is not the first person to discuss veganism and animal welfare, and Israeli chefs didn’t exactly invent tofu. Although better known for his theorem regarding triangles, the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras preached kindness toward all animals and may have been the first to mention vegetarianism. Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham wrote about discrimination against animals in 1781.

The French have already discovered that the blackness of skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may come one day to be recognized, that the number of legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum, are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate.

Bentham argued that we shouldn’t discriminate against animals because of factors out of their control; this is the same argument Yourofsky made 200 years later.

Meanwhile, gourmet vegan restaurants exist all over the world, and with more demand, more would probably pop up in locations other than Israel. While Israel boasts cultural ties to foods like falafel and hummus, other vegan staples like tofu and quinoa come from across the world. It’s easier to be a vegan now in Israel, but that’s probably true globally. So why were Israelis so receptive to the idea in the first place?

Israelis, it turns out, are culinarily and culturally primed to be vegan. They’re already used to being mindful about what they eat. Seventy-five percent of Israeli Jews keep kosher, so they’re already used to cutting certain foods out of their diets, and nearly all vegan products are already kosher.

Additionally, a lot of Israeli cuisine is already vegan. Foods like hummus, falafel, and couscous are staples of Israeli diets. “We have a lot of vegetables and fruits and lentils and grains in our diets anyway, so it’s not a huge leap to become a vegan,” Shavit said. It’s also easy to acquire vegan substitutes, explained Ziv Sandler, pastry chef at the Tel Aviv vegan bakery Seeds Patisserie. “In pastries, the main vegan substitutes would be coconut oil for replacing butter, coconut milk and fluid for replacing cream and milk, and apple puree for replacing eggs, thankfully all of which are easy to obtain in Israel.”

Economic factors also influence people’s diets. Most fruits and vegetables are cheaper in Israel than in the U.S., UK, France or Germany—in many cases, more than twice as cheap. In contrast, dairy and meat products are significantly more expensive in Israel. Limited competition in those markets—three firms have monopolized the Israeli dairy industry, while two companies rule the meat aisle—keep prices high. Sixty percent of Israel is desert, limiting space for cattle (and therefore supply) in an already-small country. As a result, two-thirds of Israel’s beef is imported, compared to the U.S.’s 8-20 percent. Tariffs, the high costs of storage and international transportation of frozen foods, a national ban on importing non-kosher meat, and “double supervision”—where supervisors deputized by the Israeli Rabbinate must certify imported meat’s kosher status even if it has already been done by a rabbi in the Diaspora—also drive prices up.

Jews and Arabs protest together in Haifa on behalf of animal rights. Photo: Anonymous for Animal Rights / Facebook

Many laws of kashrut are justified by calls to prevent animal suffering, which Israelis are translating to veganism today. “The spirit of the law is being trampled by modern-day factory farming,” Modern Orthodox Israeli rabbi Jeremy Gimpel told Tablet. Gimpel also said on an episode of his podcast that in advocating for “a sanctity to life,” Yourofsky is “tapping into something very Jewish.” Yourofsky believes that the Jewish history of suffering may also contribute to a better understanding of the suffering meat imposes on animals. “I have noticed that minorities (Jews, blacks, gays, Hispanics, women, etc.) understand oppression better than those who have always been the oppressor (white males),” Yourofsky said in an email. “So it is not terribly shocking to me that Jews are starting to comprehend that they are still actively partaking in a Holocaust that [sic] 1 million times worse than the one they experienced around 75 years ago.”

Because Israel is such a small and community-oriented country, when something big happens, word travels fast. “It’s very easy to pass the information about the reasons to go vegan,” Shavit said. It certainly doesn’t hurt that Israelis are very active on social media, with 76 percent of internet-enabled adults using social networking sites. And so when one person shared Yourofsky’s gospel, everyone started watching it.

Israel’s culture of innovation also plays a role. “We are a young nation,” Shavit explained. “We are a nation of immigrants. Our culture is still evolving. It’s still growing and changing all the time and because we came here from so many different countries and cultures, people are sort of flexible,” In Israel, “people like to try new things. They’re less scared. They like innovation.”

Israeli vegan activists frequently exemplify this innovative culture. “The Israeli activists are the most amazing activists I have ever encountered,” Yourofsky wrote.

I wish there were people that dedicated, that creative and that effective here in America. I definitely got the ball rolling, BUT THE ISRAELI ACTIVISTS definitely ran with that ball and are still running full-speed with it, which is why I have not returned. There is NO need for my presence there. They will make Israel the first vegan nation on this planet one day.

Israel also has more startup companies per capita than any other country and has 2.5 times more venture capital investments than the United States, a country with nearly 40 times the population. This, combined with a relatively high GDP per capita, has led to Israel introducing new vegan innovations, companies, and products, such as the start-up SuperMeat, which is growing vegan chicken meat from humanely-collected chicken cells. And the growing demand for vegan food prompts even more innovations in a self-perpetuating cycle.

There is no one defining Israeli factor that makes it riper for veganism’s exploding popularity than other nations. Yourofsky’s video was translated into over 30 other languages. Other religions also have dietary restrictions and moral codes for animal treatment. Other countries have Mediterranean diets, communal cultures, desert landscapes, successful startups, or vibrant social media scenes. But only Israel has all of these factors. They come together to make Israel Israel, vegan and all.

That being said, the vegan movement is spreading beyond Israel’s borders. This October, Shavit will begin her third college tour of the United States to talk to American students about veganism. The enthusiasm she sees on her tours shows her, she says, that “Israel can be an example and even a model for people from other countries to see how they can make the same change.”

![]()

Banner Photo: Photo: CityTree / flickr