A new book explores the decades of historical and political tensions that led to today, when Britain’s leading opposition party has been mired in a months-long anti-Semitism scandal.

It’s hard to think of a more contested form of prejudice in the post-war era than anti-Semitism. Particularly over the last twenty years, during which the intrusion of anti-Semitic motifs into attacks on the State of Israel have become ever more visible, the counter-claim that anti-Semitism is an historical relic revived by devious Zionists to deflect criticism of the Jewish state has gained vastly in currency.

There are few better guides to this discursive maelstrom than Dave Rich, an analyst with the Community Security Trust, an organization that provides security to the British Jewish community. Having known Rich as a personal friend for more than a decade, I can confirm that he has an encyclopedic knowledge of both anti-Semitism on the Left and other forms of extremism more generally. But I doubt that even he anticipated that, in 2016, he would be publishing a book about a problem that mushroomed, as he puts it, “into front-page news in Britain.”

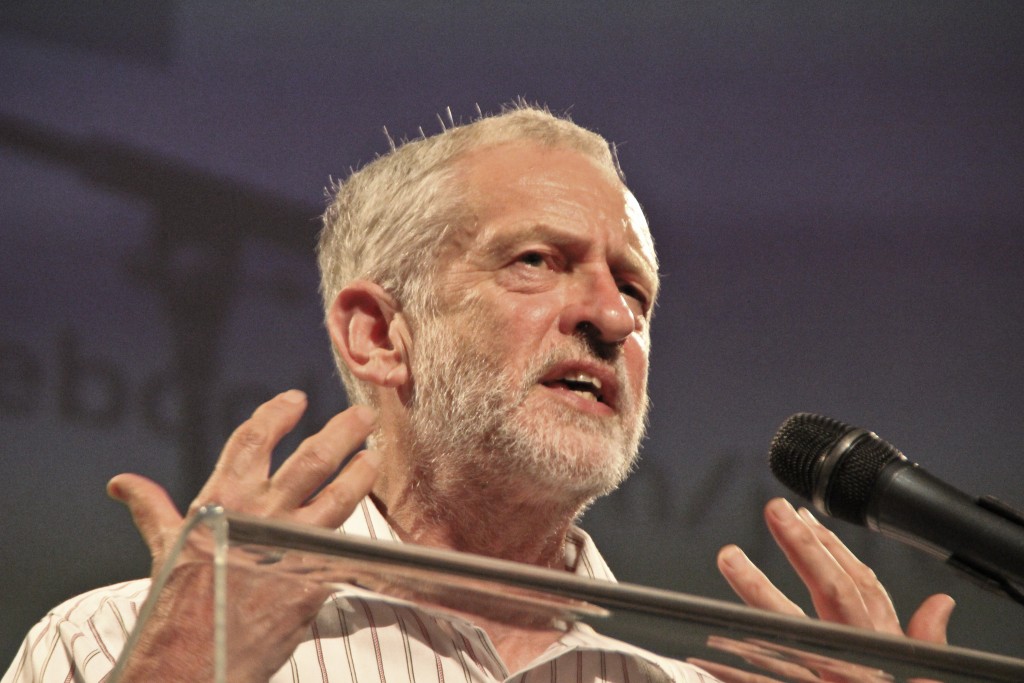

The immediate cause of Rich’s book The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism, which draws on his recent doctoral thesis, is Corbyn’s election as the leader of Britain’s Labour Party. While it contains valuable detail on the rash of anti-Semitic episodes that have accompanied Corbyn’s brief tenure, the book has a much more enduring value. Like George Orwell’s essays and broadcasts on the politics and culture of his day, the immediacy of Rich’s topic is offset by his examination of the historical provenance of the current, wretched relationship between the Labour Party and Jews in Britain. With Corbyn’s successful retention of the Labour leadership in September, when he fought off a challenge from the more centrist Owen Smith, that relationship is set to get worse.

Corbyn’s election to the leadership was not the product of a mass turn towards Labour, but of a crisis that engulfed the party following its defeat in the 2015 general election. Under Corbyn’s predecessor, Ed Miliband—who will be remembered as one of the most incompetent leaders of the party in its history of more than a century—Labour had already started veering to the Left, as the labor unions and the grassroots took aim at the legacy of former Prime Minister Tony Blair, detested by the far-Left for his participation in the Iraq War.

Still, when Corbyn announced his intention to contest the leadership, virtually no one took his bid seriously, largely because he comes from the furthest-Left wing of the party. But win he did, and as he took the helm of the Labour Party, many of the principles and policies that Blair dispensed with—such as restoring key industries to public ownership, economic protectionism, and reduced parental choice in education—came back into the frame with a vengeance.

The growing politicization of British Muslims and their high-profile involvement with the Stop the War Coalition, once chaired by Corbyn, was another key factor in uniting the disaffected Left around him. Corbyn described the participation of groups like the pro-Hamas Muslim Association of Britain as meaning that the anti-war umbrella was “one of the most important democratic campaigns of modern times.” As Rich observes,

Encouraging political engagement from British Muslims (or people from any minority) is, in principle, a good thing, but in this case with the prospect of putting radical leftists at the head of a movement with energy and numbers beyond their dreams. It didn’t stop the invasion of Iraq and it hasn’t brought freedom for Palestine, but it has changed the complexion of the left in Britain. Tony Blair’s decision to join the United States in the 2003 Iraq War opened a deep wound in the Labour movement that still has not healed, and the anger and shame felt by left-wing opponents of the war play a large part in explaining how Jeremy Corbyn became Labour Party leader.

On the foreign policy front, Corbyn represents a mix of isolationism and anti-imperialism, which explains both his cold indifference to the suffering of millions of Muslim Syrians and his embrace of Hamas and Hezbollah as “friends.” Never an intellectual force in his own right, Corbyn has been content to play the role of an enabler, particularly of the anti-Zionism that began to take shape during the late 1960s.

It is here that we come to the first of the two extraordinary insights which Rich’s book contributes to our understanding of anti-Semitism on the left. It is a commonplace that the depiction of Israel as a “settler-colonial” state emerged with the New Left, and there is ample evidence that Trotskyists were among the main proponents of this dubious theory. Rich, however, resists the temptation to portray anti-Zionism as a sole product of the various Trotskyist currents that won over successive generations of students and activists.

For one thing, while Leon Trotsky himself was always hostile to Zionism, by the end of the 1930s, with the Nazi persecution of the Jews well under way and the stench of Jew-baiting already emanating from the Soviet Union under Stalin, the “Old Man” began revising his views on the Left’s perennial “Jewish Question.” With uncanny prescience, Trotsky declared in 1938 that the logic of Hitler’s position was the annihilation of the Jews. As a result, the territorial solution to the Jewish Question, which he had always resisted on ideological grounds, became more attractive in terms of practicality and urgency.

For another, there was never a single Trotskyist position on Israel. There are many British Jewish students who remember with gratitude the interventions of a group named “Socialist Organiser,” whose guiding hand, Sean Matgamna, persistently argued that a socialist solution to the conflict in the Middle East had to include independence and self-determination for the Jews in Israel. Even among those Trotskyists who took a different position, like the Israeli revolutionaries of “Matzpen,” many of whose members decamped to London in the 1960s, there was a never-ending discussion of the relationship between class and nation, and the correct stance to adopt regarding the “reactionary Arab regimes” as well as the “Zionist state.”

Harry Pollitt, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain, gives a speech to workers in Whitehall, London, 1941. Photo: Wikimedia

All of this was rather irritating to Palestinian emigres like Ghada Karmi, a doctor living in London and one of the earliest Palestine solidarity activists. As Karmi revealed in an interview with Rich, she became tired of the talk about “the revolt of the working class and the Arab working class across the world…I found it deeply irrelevant because it ignored the fact that our problems were liberation. That’s what we were about, it was way before talking what sort of society would you create.”

Where the squabbling Trotskyists failed, Rich explains, another organization succeeded. That organization was the Young Liberals, the youth wing of the venerable political party that governed Britain for much of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth. Caught up in the New Left ferment of the 1960s, the Young Liberals nevertheless had little interest in doctrinal disputes, concentrating instead on practical solidarity campaigns against the Vietnam War, apartheid in South Africa, and similar causes in the post-colonial world at that time. Rich quotes the Young Liberal activist Peter Hellyer clarifying that his group “came towards a policy of supporting the Palestinians out of a general policy of supporting ‘national liberation movements’—as in southern Africa. ‘Worker-peasant alliances’ didn’t seem relevant to us (to put it politely).”

Rich makes a persuasive case that the Young Liberal model of anti-Zionism—in essence, uncritical support of Palestinian discourse and political and military actions—enjoyed an impact on British views on the Palestinian question that continues today. It certainly exercised a greater appeal upon activists like Ghada Karmi, as well as the parliamentarians who took up the Palestinian cause in growing numbers during the 1970s. As Rich says,

In the 1970s, groups like Palestine Action, the Palestine Solidarity campaign and the Free Palestine newspaper helped to establish the notion that Fatah and other Palestinian factions had the right to use violence, although they sometimes differed over the precise tactics used. Since then, attitudes ranging from sympathy for the motivations of terrorists to outright justification for their actions have spread beyond the radical left to become commonplace in mainstream left-wing and liberal thought.

However, while this model of anti-Zionism studiously avoided Marxist critiques of the PLO and the Arab regimes as well as the possibilities for revolution within Israel, it did drift into discussions that were arguably more bizarre and certainly more disturbing than the notion of a socialist federation of Arab and Israeli workers. This is where Rich’s second decisive contribution comes to fore, in his discussion of the British Left’s attitude towards the Holocaust.

One might say that the distortion of the Holocaust’s meaning on the British Left was a direct outgrowth of the Young Liberals’ presentation of Palestine solidarity as centered upon the desires and beliefs of the Palestinians themselves, rather than their own various far-Left political agendas. It is well known that various revisionist myths concerning the Holocaust have circulated widely among Palestinians and in the Arab world: diminishing the number of Jews murdered, blaming the genocide on “Zionist collaboration,” and outright denial that the Holocaust occurred. By the 1980s, as Rich documents, the idea that the Israelis had themselves become Nazis was uncontroversial on the Left.

The Holocaust became a political inconvenience rather than a formative event; and as left-wing opposition to Zionism and Israel has strengthened, it has been accompanied by sustained efforts to revise the left’s understanding of the Holocaust and its relationship to Israel.

With Corbyn’s election, these long-embedded views, further cemented by the far-Left’s alliance with British Islamist groups around the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, garnered unprecedented public exposure. As Rich points out, by the middle of 2016, up to twenty Labour members, including the parliamentarian Naz Shah, had been suspended or expelled for alleged outbursts of anti-Semitism. Also among them was former London mayor Ken Livingstone, who seized on every opportunity to argue, based on crackpot sources like the writings of the American anti-Zionist Lenni Brenner, that Hitler himself had been a supporter of Zionism “after his election in 1932” [sic].

Corbyn’s response was to set up an internal inquiry into the problem of anti-Semitism in the Labour Party headed by Shami Chakrabarti, a civil rights activist. After what many considered a pitifully short period of actual inquiring, Chakrabarti issued a cautious report that argued for greater sensitivity when it came to the invocation of the Holocaust, but left unaddressed deeper issues that stretch all the way back to the nineteenth century, when large parts of the nascent European Left opposed Jewish emancipation in the name of anti-capitalism.

Shortly after Chakrabarti issued her report, Corbyn elevated her to the House of Lords—an institution he’d reviled for his entire career—leaving British Jews to contemplate, in the words of Rich, how and why Labour had failed to grasp “the peculiar logic of how left-wing anti-racism can foster anti-Semitism.” Critically, Rich argues that the Left’s failure to acknowledge the “permanent shadow” cast by the Holocaust, along with its dogmatic contention that anti-Semitism is always and only a feature of Right-wing politics, means that it cannot understand “why most Diaspora Jews relate to Zionism and to Israel in the way that they do.” That observation was again dramatically highlighted just weeks after the Chakrabarti Report was published, when Jackie Walker, the vice-chair of the pro-Corbyn faction “Momentum,” complained that she couldn’t find “a definition of anti-Semitism I can work with,” and then wondered aloud, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Holocaust day was open to all people who experienced Holocaust?” These comments earned Walker her second suspension from the party for anti-Semitism. The first was back in May 2016, after a Facebook post in which she parroted the antisemitic hoax that Jews were the “chief financiers” of the slave trade.

The consistent problem posed by Jackie Walker and those like her cannot be solved as long Corbyn’s ability to understand anti-Semitism properly is restricted by his world-view. As Rich argues,

He sees it only as a far-right phenomenon: part of a broader xenophobic politics that is against diversity and stigmatises refugees and minorities…Describing anti-Semitism in this way suggests that those Labour members who have been suspended or expelled for alleged anti-Semitism were guilty of parroting ideas and language that were alien to the left…If Corbyn is right, then these individuals were anomalies from which there is little to learn about left-wing attitudes to Jews or Zionism.

As comprehensive and enlightening as Rich’s book is, it does largely overlook one important consideration. Anti-Zionism became a feature of the British Left’s landscape during a period of rolling political failures, rather than successes. As elsewhere in Europe, the New Left in Britain fizzled out into rival factions and projects. Under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in the 1980s, the labor unions were beaten into submission, a process symbolized by her bitter war against the National Union of Mineworkers in 1984-85, which resulted in entire working class communities in the North of England and South Wales being decimated. As Labour and other Left activists set about drafting resolutions in support of the Palestinians—including the demand for the banning of university Jewish Societies, on the grounds that “Zionism is racism”—the traditional proletarian battlegrounds of socialist politics became sites of defeat. Perhaps that explains why the modernizing Tony Blair, vilified by Corbyn as a “war criminal,” remains the only Labour leader to have actually won a general election since the dawn of Thatcherism in 1979.

Still, Rich ends his book on an optimistic note. As bruised as the relationship between Labour and the Jews is, he asserts that the historic identification of British Jews with the party is not beyond repair. Yet as long as Corbyn remains leader, it is hard to conceive of a reconciliation happening. Rich’s elegant dissection of why that is the case will remain unsurpassed for a very long time.

***

The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism

By Dave Rich

Biteback Publishing, London, 2016 (292 pages)

Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Lefts-Jewish-Problem-Jeremy-Anti-Semitism/dp/1785901206

![]()

Banner Photo: Garry Knight / flickr