In a country where raising kids is the ultimate value, marriage becomes less urgent than adoption and surrogacy.

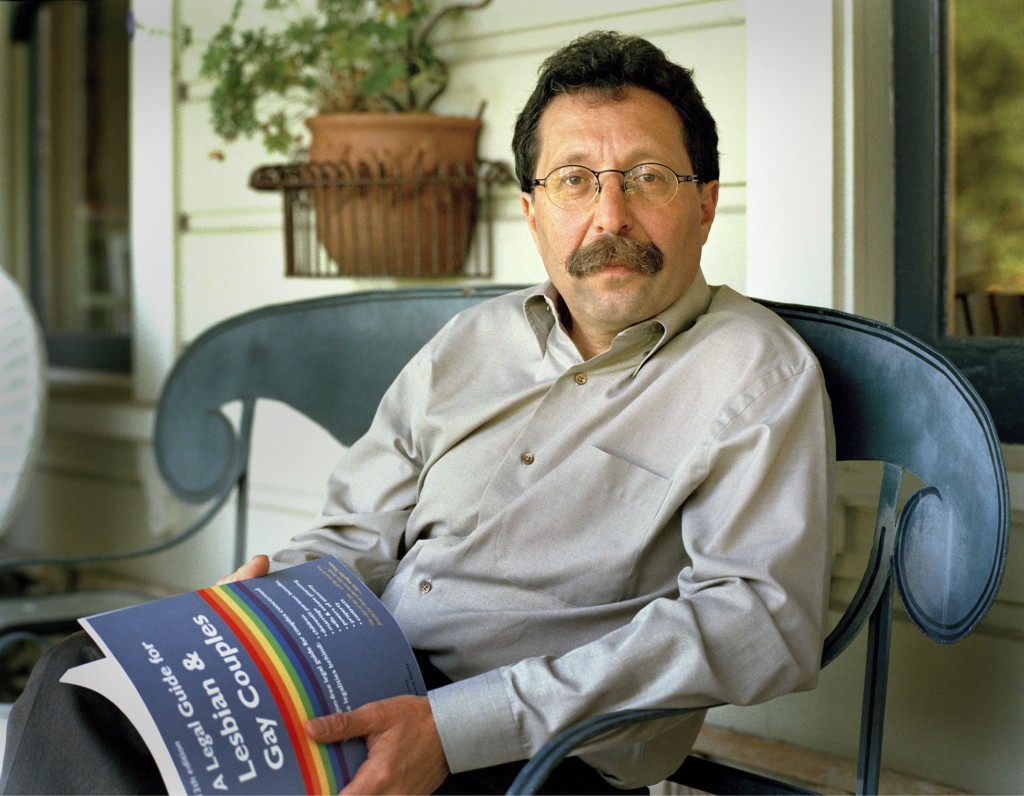

A refugee lawyer, a transgender specialist, and six other people sit in a circle in an empty classroom on the second floor of Tel Aviv’s Gay Center. They are here for the inauguration of Israel’s first-ever LGBT legal clinic. The evening’s keynote speaker is Frederick Hertz, an American legal expert who specializes in gay marriage. He describes a recent case he handled, in which a gay couple, one of them transgender, got married in Las Vegas as a man and a woman. Then they moved to California and wanted their respective healthcare benefits. “So the question,” Hertz says, “was how to register that same-sex couple when they had been married as an opposite-sex couple.”

The crowd stares blankly, some playing with their telephones. One attendee, wearing skinny jeans and Converse sneakers, breaks the collective yawn by quoting a New Yorker cartoon, republished in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, to convey how Israelis feel about the American debate over gay marriage: “Gays and lesbians getting married — haven’t they suffered enough?”

But down two flights of stairs, past a photo exhibition of Israeli drag queens and a poster for a Hebrew version of “Angels in America,” a much livelier conversation is taking place in the Center’s bar. Through a cloud of cigarette smoke and techno music, a group of activists is talking about what really matters to Israeli gays today: surrogacy.

Holding court at a wicker table is Michal Eden, who became Israel’s first openly gay elected official when she won a seat on Tel Aviv’s city council in 1998. She marvels at the fact that, while surrogacy is illegal for gay couples in Israel, an increasing number of them are paying foreign women to have their babies overseas.

“I’ll tell you, I see it as a revolution,” she says. “The fact that gay men from Israel can have a kid from India or from the United States and can raise it as part of a family, as a Jewish Israeli gay family.”

Yuval Eggert, the Gay Center’s executive director, drops by to join in the conversation. He can’t stay long, since he is still on paternity leave (having just had a baby via a surrogate in India) and can barely keep his eyes open. “Ah, mazal tov!” Eden calls out.

Also shmoozing with the crowd is Itai Pinkas, a former Tel Aviv city councilman who had a child with his partner Yoav in 2010 via a surrogate from Mumbai. “A gay thirty-something man with a partner and a baby or two can definitely be considered a typical Tel Aviv specimen,” he recently declared in a column for the Israeli daily Maariv.

But as gay men of means are increasingly willing to pay the hefty price of traveling abroad to find a surrogate, less well-off gays in Israel wonder why they are still denied the procedure at home — which has been legal for straight couples in Israel since 1996. The problem is particularly striking in a country that touts its strong record on gay rights. Israel offers broad legal protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation, and allowed gays to serve in the military decades before the U.S. Out Magazine describes Tel Aviv as “the gay capital of the Middle East,” and an American Airlines poll recently dubbed it the world’s top gay travel destination. Indeed, Israel is so proud of its accomplishments on gay rights that it has even been accused of exploiting them internationally in order to “pinkwash” its treatment of the Palestinians.

This paradox has pushed Israeli gay activists and their allies toward making surrogacy rights their top political priority, much as marriage equality is for American gays. And like marriage, surrogacy has become a lightning-rod for controversy, touching on some of the most loaded issues facing Israel today: sexuality, gender, demography, and religion.

To a large extent, the lack of political interest in marriage equality among Israeli gays reflects a growing apathy about the official recognition of marriage in general. In Israel, all matters relating to marriage and divorce fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of religious courts — for Jews, this means the rabbinate. Israel has no institution of civil marriage, and thus can make no provisions for couples who fall outside traditional religious parameters. As a result, many straight couples in Israel do not legally marry, either because their marriages are unacceptable under religious law (such as interfaith marriages), or because they don’t want to deal with the onerous process of getting the rabbinate’s approval. “They have a private ceremony with the whole shebang and the wedding dress, but it’s not a formal marriage, and they don’t register with the Ministry of the Interior,” says Victoria Gelfand, one of Israel’s foremost civil rights attorneys focusing on gay family issues. “No one asks, ‘Are you actually married or are you just pretending? ’ Once you have a wedding band, no one asks whether you are a heterosexual or a homosexual couple.”

According to a new report by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, the number of Jewish couples who live together without marrying is 2.5 times greater than it was a decade ago. Such couples — whether gay or straight —have been granted the status of “reputed” or common-law spouses by the Israeli Supreme Court, which gives them many of the same civil and legal rights as formally married couples. As a result, gay couples in Israel have far more rights than their counterparts in the U.S., which is part of what makes the issue of marriage equality seem less urgent. Unlike in America, moreover, getting married in Israel carries certain practical disadvantages, such as additional taxes and less paternity leave. And since all marriages performed overseas have been recognized in Israel as of 2006, gay couples who really want to get married can do so abroad.

Thus, it is not that gays are not interested in the right to marry; it is just so far from the current conception of marriage in Israel, and so many Israelis — gay and straight — have found easy ways around it. The fight for marriage equality is folded into the larger fight in Israel against religious control of the legal system, which extends far beyond the gay agenda.

So if marriage is not the Holy Grail for gays seeking equality and acceptance in Israel, what is? Increasingly the answer has to do with having children. “We Israelis chase heritage,” Gelfand says. “When gay people come out of the closet here, the reaction of their parents is, ‘Does this mean you won’t have children?’ They’re obsessed with ancestry.” As one Israeli gay activist put it, “We’re a country full of Jewish mothers. What do you expect?”

Religion’s heavy influence on Israel society, while it limits gays’ ability to marry, also makes Israeli culture “very family-oriented,” says Doron Mamet, who founded a surrogacy consulting firm in Tel Aviv for gay couples. “In Israel, if you don’t have your family, you don’t exist. In order to be part of normative society, you need a family.” The recent Central Bureau of Statistics report found that 75 percent of Israeli couples have children.

Having children in Israel carries a certain nationalist resonance, as well. Israel struggles to retain a Jewish majority in the land it controls between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. According to some estimates, however, the Arab and Jewish populations are coming precariously close to parity. This is part of the reason why Israel’s policies on in-vitro fertilization (IVF) are among the world’s most liberal, and why IVF is generously subsidized through the national healthcare system. (Israel leads the world in most IVF treatments administered per resident, with a ratio that is 13 times that of the United States.) “In my conversations, I hear having children described as the queer contribution to the building of the Jewish state,” says Frederick Hertz. “I don’t think an American gay dad would talk about having kids as building the American state.”

“To be parents and reproduce, to produce Jews, is part of the Zionist ethos and very important to Israel’s demographics,” comments Eyal Gross, a law professor at Tel Aviv University. “You’re a good gay, you brought us nice new children, many children—this is the ticket to normalization, much more than marriage.”

Israel’s obsession with having babies would seem to make it fertile ground for surrogacy rights. But while the religious community in Israel has been the primary driver of Israel’s generous subsidies and lax regulation of IVF treatments, it was more cautious to embrace surrogacy. The unclear parentage produces complex Jewish legal issues about incest and adultery, as well as questions about whether the baby follows the religion of the surrogate or the egg donor.

Israel’s ban on surrogacy – dating back to 1988 – was only challenged in 1995 by an Israeli couple, in which the wife had lost her uterus to cervical cancer. Though the Ministry of Health settled the case (making a one-time exception for the couple), the Israeli government agreed to set up a commission to investigate its surrogacy policies.

According to D. Kelly Weisberg, author of The Birth of Surrogacy in Israel, “This was the first committee in the history of Israel, to study issues that were related to women, that actually was composed of half-women members.” This balance was further tipped when one of the two rabbis on the committee resigned after being appointed one of Israel’s chief rabbis. The committee’s official recommendation was to legalize surrogacy.

“To be parents and reproduce… is the ticket to normalization.” Eyal Gross, Tel Aviv University

The report would have likely languished in the Knesset under the opposition of Israel’s religious parties. But soon after its release, the Supreme Court annulled Israel’s surrogacy ban in response to a case brought by a woman who was born without a uterus (and soon joined by 49 other plaintiffs). With five and a half months to enact a replacement for the ban, the Knesset adopted many of the commission’s recommendations – legalizing surrogacy but within a strict regulatory framework.

The final law reflects deeper tensions within Israeli society. On the one hand, it includes many progressive elements, such as state subsidy of the process, as well as mandating that approval committees be made up equally of men and women. But in concession to the religious parties, it mandated that the surrogate be unmarried (which went against the commission’s recommendation), unrelated to either of the parents, of the same religion as the parents, and that the mother’s egg (not the surrogate’s) and the father’s sperm (not a donor’s) be used – measures to mediate some of the rabbinic concerns about the process. Perhaps the most limiting condition in the new law was that the process was only legal for married couples in Israel – which, by excluding all singles, made the process out of reach for gays domestically.

With both surrogacy and adoption prohibited for gays in Israel, many gays in the late 1990s started to adopt children from foreign countries – particularly Guatemala, Russia, Ukraine, and other Eastern European countries. But in recent years, many of these countries have also prohibited gay couples from adopting. “The couples would get to the agency and fill out all the forms and things, and at the last second it would be, ‘Oh, no, we can’t get the child,’” Gelfand recounts. “So no one told them anything explicit, but the result was that somewhere around 2004-2005, gays could not adopt internationally any more.”

One alternative to adoption is co-parenting – finding a single woman to have a baby with one member of the gay couple, and then raising the child in coordination with her. These arrangements often end badly, however. “They expect things to be easy, and they say, ‘Oh, we’re with friends’ but they don’t necessarily agree on how to raise a child,” Gelfand says. “They don’t always bother to make a contract that defines their parentage: legal guardianship and custody, physical custody, visitation rights.” Couples often find themselves prevented from moving too far away from the birth mother; or, if something happens to the biological father, the birth mother exercises her rights over the adoptive father.

The 2008 financial crisis, which Israel weathered relatively well, sent foreign currencies spiraling, making overseas surrogacy an increasingly affordable option for gays in Israel. “Every few days, there is some new clinic or new options in different countries,” says Gelfand, as she sits in front of six oversized filing cabinets labeled “Surrogacy.” A framed photograph of a gay couple holding a baby – her clients – rests on her desk. In her estimation, dozens of agencies have opened around the world in recent years, many of them targeting Israeli gays by organizing events and panels, and putting ads in gay specialty publications. Last month, the American-based support organization Men Having Babies held its first-ever international surrogacy conference in Israel, with fourteen local and international surrogacy groups co-sponsoring the event. According to the official program, the conference included a panel on the merits of religious conversion for babies born through surrogates, a Kabbalat Shabbat with surrogacy families, and a “Gay Parenting” exhibit, as well as break-out sessions and “speed group consults” that allowed participants to quickly interview the various clinics and agencies in attendance. According to participants, more than 200 people attended the event – which conference organizers said was the same size as similar conferences in New York and Barcelona, despite Tel Aviv’s significantly smaller population.

Because the government does not regulate the practice, there are no formal statistics on Israelis who seek surrogates overseas, but Gelfand estimates that 80 percent of them are gay couples or singles. A recent public meeting on the topic attracted more than 400 attendees, says Hertz, who had come to Israel to study marriage equality but quickly shifted his focus to the rise of surrogacy. According to John Weltman, founder and president of Circle Surrogacy in Boston, 10 percent of his clients are Israelis, and he has helped more than 50 gay Israeli couples have children.

“I don’t think an American gay dad would talk about having kids as building the American state.” Frederick Hertz, American gay rights expert

Mamet founded his agency, Tammuz, after going through the surrogacy process himself in America. “We have our babies, healthy, happy – and expensive,” he says as messengers rush in and out of his office picking up ultrasound DVDs or dropping off legal documents. He started the firm as a part-time job while he was taking care of his new infant, but in the four years since then, it has turned into a full-time occupation with five additional employees. “It started with one or two couples a year, but then it just became more and more popular, and now I see hundreds of couples a year – and I’m not the only agency,” he says, scrolling down the firm’s Facebook page, which is covered with pictures of his clients proudly showing off their newborns.

All of this has led to what the Jerusalem Report describes as “Israel’s recent ‘gayby’ boom.” Even if only a small slice of Israel’s gay population has children, they have become highly visible in the gay community. One of Israel’s leading cable channels just launched “Mom and Dads,” about a gay couple raising a child, starring three of Israel’s most popular actors. The main advertisement for last year’s world-renowned Tel Aviv gay pride parade – on a massive billboard overlooking the city’s Rabin Square – depicts a gay couple playing with their toddlers, both of whom were born through surrogates arranged by Mamet. “What I call the ‘gay exception’ for having kids is over in Israel,” Hertz says. “Having kids is the new norm.”

The idea of gays having children has become so common in Israel that gay men are now feeling the same pressure to reproduce as their straight counterparts. “Do you know how many times people have asked me, ‘Why don’t you want children?’” Gross complained. “Once people see it exists, the pressure to do it is greater.”

Walking down the street in Tel Aviv, Hertz is exasperated because these new trends have jammed his American-tuned “gaydar.” “Straight men in Israel are much friendlier, more voluble, dress better, and have better haircuts than straight men in the U.S.,” he says. “So when I see two guys pushing baby carriages, I can’t tell if they are two straight guys filling in for their wives or a gay couple.”

The ubiquity of babies born via overseas surrogates has jumpstarted the movement to secure surrogacy rights for Israeli gays. “Once it increases, people see it’s possible, then they want it,” Gross says. “Sometimes you want the idea but it seems very theoretical and far away. But once you see it exists, you say, ‘Oh, it’s possible!’”

Even those who can afford surrogacy are agitating for domestic rights, because the Israeli government is making it increasingly difficult for couples who use overseas surrogates to prove parenthood when the children are brought back to Israel, requiring blood tests and extensive paperwork. “They check everything with such a magnifying glass you wouldn’t believe,” says Gelfand, who spends much of her time guiding her clients through the convoluted process. Mamet is in the process of contesting these requirements in the Supreme Court. The Israeli government also refuses to recognize the non-biological parent of children born through surrogacies overseas (even if they are listed on the foreign birth certificate), forcing that parent to go through an onerous adoption process when they return to Israel. “This is not like a second-parent adoption in the U.S. that takes a few weeks,” Gelfand says. “Why should people have to wait as much as three years to be legally acknowledged as parents here?” The Israeli Supreme Court recently heard two cases challenging this restriction, brought by gay couples who had babies with surrogates in Pennsylvania where both were listed as parents on the birth certificate.

A January 2013 decision by officials in India—the most common destination for Israelis seeking surrogates – limits “medical visas” for foreigners seeking surrogacy to married heterosexual couples. Numerous couples and agencies are turning to riskier options, such as Thailand, where surrogates are considered the legal mother of the child, and even genetically related fathers can only be considered a legal parent if they are married to the birth mother. Others are hiring Nepalese women to trek across the border to India to receive IVF treatments and then return to Nepal for birth, where surrogacy laws are more lax. Though activists are working to overturn the new Indian restrictions, thinning international options add to the urgency surrounding the issue of domestic surrogacy rights in Israel. More than 250 people came to a recent event that Mamet organized to discuss the implications of the India restrictions. “The topic is quite hot,” Mamet said, “and people are concerned.”

There are even religious gay groups in Israel who argue that because of the difficulty in finding Jewish surrogates overseas, legalizing surrogacy for gays in Israel would allow “Jewish eggs in Jewish mothers,” as Hertz puts it. “I speak to leaders of the modern Orthodox gay community, and now they’re saying that being gay does not exempt us from the obligation of having children.”

The issue became a flashpoint for gay activists and civil rights groups in 2010 when a Jerusalem family court judge refused to authorize a DNA test for a baby born to a gay couple via an Indian surrogate—a key step to getting Israeli citizenship for the child. “If it turns out that one of the people sitting here is a pedophile or a serial killer,” said the judge, “these are things the state has to check.” YouTube and social media sites lit up with outrage and support for the cause of surrogacy rights.

Mamet describes a “wave” of activism around the issue in recent months, led by new groups with names like “Surrogacy for Homosexuals in Israel” and “Surrogacy Rights for LGBT Parenting in Israel.” Rainbow Families, an annual convention for gay families, has also helped mobilize activists on the issue. One particularly poignant ad portrays a gay couple gleefully playing on the beach with their flaxen-haired young daughter, who is then abruptly taken away by two black-clad men in sunglasses. “Don’t let anyone take away your dream,” the subtitles read in Hebrew as piano keys strike in the background. “Surrogacy for gays is illegal in Israel. We also want a family and children.”

The ad has helped garner thousands of signatures for a petition to change Israel’s surrogacy laws. “While Western countries allow same-sex couples to have children through the process of surrogacy, Israel remains dark, depressing, and mainly, far behind,” says the petition’s introduction. “Israeli law should allow anyone who wants to start a family, and anyone who wants to help a family, the freedom to exercise their fundamental rights.”

In 2003, a case brought by a lesbian who wanted the right to use a surrogate was sent to the Knesset by the Supreme Court. A committee was formed to explore the issue, but eventually decided not to change the law. “They said, ‘It worked so well during the 10 years that surrogacy has been legal for straight couples that we should leave it as is,’” Gelfand explains. “‘So well’ to them is that we were only having 20 births a year in the whole country via surrogacy.”

Some gay activists are heralding a new report by the Ministry of Health that recommends allowing gays the option of using an “altruistic surrogate”—someone who agrees to carry a child without receiving payment. Currently, there are no restrictions on how much straight couples can pay for surrogates. The report expressed concern that legalizing “commercial surrogacy” for gays would result in “emptying the whole market for the rest of the couples,” says Gelfand. “They say that the main users of the law are heterosexual couples with health issues, and they should remain the primary issue of concern.”

Veterans of the battle are not satisfied by the report. “I think they tried to be liberal there, but they basically did the opposite,” comments Mamet. “It’s basically saying gays cannot do it,” because it is so difficult to find altruistic surrogates. “And to say in a formal committee that they understand your need to have children, but there are people who are Class A, and you are Class B – it’s a problem.”

There is little hope, however, that the recommendations will become law, because Israel’s religious parties hold disproportionate sway in the Israel’s parliament. In an unlikely alliance, feminist groups are also mobilizing against broader legalization of surrogacy, seeing it as a form of exploitation toward women. Gay rights activists are pinning their hopes on the Supreme Court, which has traditionally been Israel’s most progressive force for civil rights. One surrogacy rights case was filed by a gay couple in 2010, but the Court convinced the plaintiffs to withdraw it while the Health Ministry committee examined the subject. Not satisfied with the final report, the couple intends to resubmit their petition soon.

There is growing optimism, however, that the disconnect between Israel’s liberal policies toward gay rights and its restrictive policies on gay surrogacy will force a reckoning sooner rather than later. “The issue has been raised too many times,” Gelfand says, “and they know they can’t neglect it and just say, ‘Don’t go there.’”

![]()

Banner photo: Miriam Alster/Flash90