Israeli politicans are using social media in ways that reflect the dynamism, creativity, and tech savvy of the Start-Up Nation. Is it good for the West’s political culture?

Someday, historians may look back and say that the social media revolution finally conquered the Israeli political scene at the end of July 2013. One evening, the Knesset was working hard to pass the new Finance Minister Yair Lapid’s first budget in a marathon all-night session. At the end of a seemingly interminable series of speeches, all Members of Knesset had to do was press the “for” or “against” button in front of them as article after article of the seemingly endless bill was read.

As is usually the case with such bills, party-line discipline had been imposed, and Justice Minister Tzipi Livni was even flown in from peace talks in Washington to bolster the coalition’s vote. But as the button-pushing stretched into the night, the MKs were mostly bored out of their minds. Plenty of them brought books, strategically tilted so the press could see them and admire their intellectual proclivities.

Naftali Bennett, however, Economy Minister and head of the national-religious Bayit Yehudi (“Jewish Home”) party, eventually got bored of his English-language biography of Abraham Lincoln. So he turned to Facebook.

“Go ahead and ask!” he posted. “Right now I am in a marathon of votes in the Knesset plenum. I have some free time, and I would be happy to hear ideas/opinions/questions from the public.” Nearly 1,700 of Bennett’s 188,000-odd Facebook fans commented on his status. But one stood out.

“When are you coming home?” Bennett’s wife, Gilat, asked.

The answer came at a minute to midnight: “Darling, I will be stuck here voting until late. Tomorrow night. Good night and kisses to the little ones.”

The next day Bennett posted a photo of his son with the caption: “While I was in the Knesset voting on 4,700 objections to the budget, my youngest son David Emmanuel started walking for the first time. I can’t believe I missed it!”

Bennett’s personal tone might seem unusual to American readers, but it is not unusual in Israeli politics. On the contrary, while Israelis have always demanded a certain earthiness and accessibility from their politicians, it is only with the emergence of social media—and especially Facebook—that they have come to expect immediate, accountable answers, constant engagement, and direct real-time access to their favorite elected representatives in all their fallible selves. It has turned the political discourse in Israel into something fascinating and dynamic; and at a time when democracies in many countries, and especially the US, seem mired in dysfunction, it is a model worth giving serious consideration.

The use of social media as a political tool is not new, nor is it unique to Israel. Indeed, it has become an important tool for politicians around the world. Many have noted, for example, the skill with which the 2008 Obama campaign used social media to connect with voters, and young voters in particular. But in Israel, perhaps more than anywhere else, it has become essential to any politician who wants to keep his or her name in the news and on potential voters’ minds; not only in regard to policies or ideology, but in a deeply personal way.

This is very much in contrast to American politics. It’s hard to imagine an American politician using his public Facebook page to tell his wife when he’ll be home or post videos of his child learning to walk. In the U.S., the most personal uses of social media by politicians have been of a scandalous nature, the “sexting” affair that ultimately toppled New York mayoral candidate Anthony Weiner being the most famous example. Perhaps as a result, most American politicians rely on an impersonal social media style, leaving it to their staffs and consultants to craft their online persona.

Senator Cory Booker, for example, considered by many to be a master of social media, is a good example of how different American politicians’ use of social media is from their Israeli counterparts. Booker is unquestionably deft at using his Facebook and Twitter pages to keep his constituents informed and up-to-date, but for the most part, there isn’t much there to write home about: Photos from ribbon-cuttings and other campaign events interspersed with bromides like “when they doubt you, love them for giving your dreams greater courage” (which he has tweeted on at least four separate occasions). Booker’s Twitter feed is full of similar encouraging statements about shaping your own destiny and expressions of thanks to online supporters. There is little that shows his fallibility; on the contrary, his social media self-promotion (he rescued a woman from a burning building, he saved dogs left to freeze outside in the snow, etc.) creates the façade of a superhero.

Social media has become essential for Israeli politicians hoping to maintain voters’ attention.

On the other side of the aisle, in the deeply conservative state of Texas, Governor Rick Perry’s social media presence is even less personal than Booker’s. Perry’s Facebook page is filled with the usual photos and videos of himself speaking to the media or at various conferences. His Twitter feed is similar, with a few jabs at Obamacare for variety. Nothing, in other words, that would not appear in any other kind of PR vehicle.

This is the social media style followed by almost all American politicians (with Sarah Palin being a notable exception). In Israel, however, politicians tend to leave little doubt that they write most of their own social media content. At the very least, they try to make it look that way. The reason is that politics, like pretty much everything else in Israel, is deeply personal.

A small country in which everybody often seems to know everybody else, or know someone who knows someone who knows everybody else, Israel is a society in which the personal touch is everywhere, with politics being no exception. This quality is popularly known as “sachbak,” loosely translated as “being chummy,” and it is pervasive and essential in Israeli society. For politicians, it is indispensable. If a politician is not seen as real, as “sachbak,” Israelis get suspicious.

The cost of defying this is high. When ex-Defense Minister Ehud Barak, who is famous for his interpersonal ineptitude, tried to run in the 2009 elections under the slogan “Not sachbak, but a leader,” his political support collapsed. That sachbak found its way on to politicians’ Facebook pages should not be surprising. In a country where the prime minister is known by his childhood nickname “Bibi” and the defense minister goes by his army moniker “Boogie,” it was inevitable.

This proved to be particularly important during the 2013 general elections, in which most candidates made use of social media to get their message out. But Yair Lapid, who quit his job as a popular television personality to found the Yesh Atid (“There is a Future”) party, turned “Facebooking” into an art form; so much so that if you Google “Facebook” in Hebrew, Lapid’s page is one of the first results.

To a great extent, Lapid’s social media campaign was so effective because he used it to bypass the mainstream Israeli media in order to cultivate a direct, personal relationship with the electorate. When he left his chair as anchor of Channel 2’s Friday night news broadcast—and for some time after—he refused to speak to the press and turned down all requests for interviews, communicating with the public only through his Facebook page.

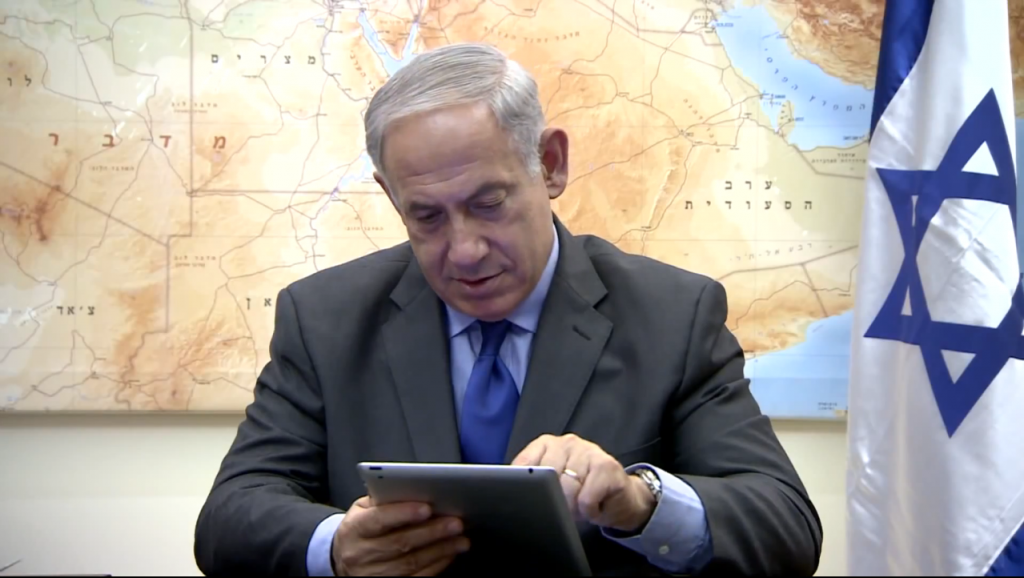

In a Rosh Hashanah greeting posted to YouTube, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu plays Candy Crush. Photo: Yair Rosenberg / YouTube

It proved to be a stroke of genius. In particular, Lapid brilliantly exploited his already high media profile in order to connect with voters via social media. The son of Holocaust survivor, outspoken journalist, and former justice minister Yosef “Tommy” Lapid, Yair Lapid had spent decades cultivating an image as “ha’chi yisraeli sh’yesh,” literally, “the most Israeli [person] there is”—the personification of his generation of native-born secular Israelis. On his wildly popular talk show, he interspersed serious interviews with figures like Stephen Hawking with wearing a black t-shirt and asking guests “What is most Israeli in your eyes?” In his regular newspaper column, he emphasized the personal, mixing his political opinions with stories about his famous family.

As a result, when speculation began that he was soon to form his own party, tens of thousands of Facebook fans “liked” and commented on his every post. The hype generated by his social media profile ensured that, by the time he announced the formation of Yesh Atid, it was already clear that he was a force to be reckoned with.

Nor is adeptness in social media limited to Lapid or the Israeli Left. Another newcomer to Israeli politics who skillfully employed social media to boost his political profile was a relative unknown: Naftali Bennett, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s former chief of staff and a high-tech millionaire. After Bennett won the leadership of the Bayit Yehudi party, he made sure to maintain an active and personal Facebook presence, constantly writing posts that addressed his followers as “friends” and “brothers and sisters.” He regularly posted photos related to service in the IDF, including his own. This carefully cultivated tough guy image was both serious and playful, appealing to his hawkish supporters and spawning a series of Internet memes that poked fun at his image through “Chuck Norris jokes,” such as “Naftali Bennett kills two birds with one stone” or the more political “Naftali Bennett builds a house in Jerusalem and Obama comes to visit.” Bennett’s ultimate success in revitalizing the divided and politically moribund national-religious movement proved the effectiveness of this approach.

Newer parties can rise to prominence through social media, but it leaves them vulnerable to embarrassing gaffes.

In fact, their skillful and constant use of social media paid off in spades for both Lapid and Bennett, who proved to be the two biggest winners of the 2013 elections. Lapid, in particular, shocked the country by doing twice as well as the polls indicated. What the two men had in common is that their use of social media helped them cultivate an image as emissaries of a “new politics,” giving them a large following among young voters of various ideologies. They are now the most popular Israeli politicians on Facebook, outdone only by Netanyahu, who is, after all, the prime minister, and enjoys a much larger international following than they do.

Lapid used the term “new politics” to describe a type of politics that would respond to Israelis’ need for authenticity and honesty from its politicians, a desire frustrated by corruption and backroom wheeling and dealing. Bennett quickly latched on to the phrase as well. Portraying themselves as political outsiders, they both claimed to understand what “real Israelis” need and want. And they held that what Israelis needed and wanted was to deal with the cost of living, an end to national service exemptions, and other domestic issues rather than, say, the Iranian nuclear threat or the Palestinians. Needless to say, they succeeded. Had it not been for the power of social media, and the personal touch they brought to it, it is quite possible that they would not have done so, and the issues they sought to deal with—despite their importance—would have gone unaddressed.

Yet there are very good reasons why American politicians stick to the polished, less-authentic, overtly engineered forms of social-media presence. As American politicians like Anthony Weiner have discovered, the power of social media is very much a double-edged sword. Personal, largely spontaneous and unedited posts by politicians—particularly those with government responsibilities—can easily result in embarrassment, offense, and even scandal. In the Israeli context, however, even gaffes have helped foster a new sense of accountability, encouraging instantaneous criticism and forcing candidates and officials to take real-time responsibility for their statements and actions.

Lapid, Israel’s master of social media, found this out on April 1, 2013, when he introduced Israel to Mrs. Riki Cohen. Riki Cohen was a fictional character created by Lapid—who was now finance minister in the new government—in order to illustrate the economic problems faced by the average Israeli middle-class woman. On his Facebook page, Lapid posted that he had interrupted a finance ministry meeting about the deficit in order to tell advisers, lawyers, and economists that he wanted to talk about Riki Cohen. This, Lapid wrote, is what he said to them:

Riki Cohen is from Hadera. She is 37, a high school teacher. Her husband works in high-tech in a non-senior position, and together, they make a little over NIS 20,000 a month. They have an apartment and they go abroad once every two years, but there is no likelihood that they’ll be able to buy a home for one of their three children. We’re sitting here, day after day, talking about balancing the budget, but our job isn’t Excel spreadsheets; it’s to help Mrs. Cohen. We have to help her, because she’s helping us. Because of people like Mrs. Cohen, our country exists. She represents the Israeli middle class, people who wake up in the morning, work hard, pay taxes, are not part of a special sector but carry the Israeli economy on their backs. What are we doing for her? Do we even remember that we work for her?

Lapid was trying to portray himself as the tribune of Israel’s 2011 middle-class social justice protests. But it didn’t take long before commentators and others were ripping Lapid’s post to shreds. In particular, they attacked Lapid’s claim that “Mrs. Cohen” was an ordinary middle-class Israeli. The median gross salary in Israel, they claimed, was NIS 6,655 per month, meaning that Mr. and Mrs. Cohen’s combined income of NIS 20,000 per month put them in the top 20% of Israeli wage earners.

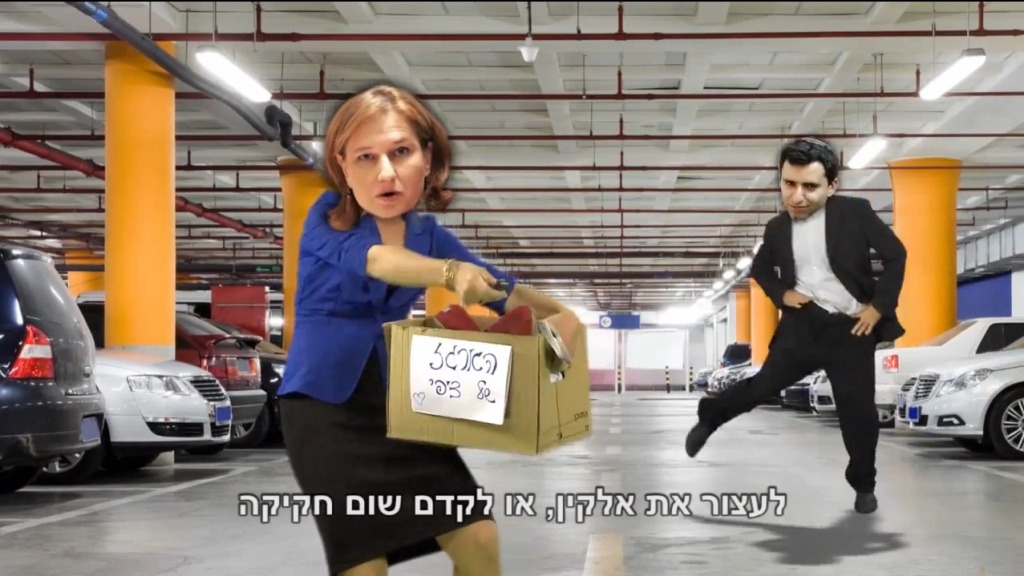

A clip from “Elkin Style,” a “Gangnam Style” parody that launched Ze’ev Elkin into political prominence. Photo: Netanel Noyman / YouTube

Opponents of the new government leapt on Lapid’s post in order to blast both the finance minister and Prime Minister Netanyahu, the bête noir of the 2011 protests. Riffing off the biblical Isaac’s declaration in the affair of Jacob and Esau, “The voice is the voice of Lapid,” wrote Shelly Yachimovich, leader of the opposition, “but the hands are the hands of Netanyahu.” At the instantaneous speed of social media, Riki Cohen went from an artful piece of propaganda to a weapon in the hands of Lapid’s enemies, who employed it to portray Lapid and the new government as detached from the realities of Israeli life.

The Riki Cohen incident illustrates one of the pitfalls of social media—it can cause politicians to become so obsessed with crafting their own image that they forget the difference between image and actual governance. Lapid’s early success seems to have blinded him to the fact that his “ultimate Israeli” act was simply a literary device helping him craft perfectly readable and relatable statuses that would bolster his campaign. He couldn’t see that the time had come to stop campaigning and start working.

Political blogger Tal Schneider, who followed politicians’ use of social media throughout the election campaign, told me at the time,

Lapid needs to move from being a writer on Facebook to someone with the responsibility to implement things. Even if he thinks he’s writing fiction, people want to know, when the finance minister writes [Mrs. Cohen makes NIS 20,000] if it’s before or after taxes. It’s not clear if he means middle class or upper-middle class.”

There is no doubt that Lapid is charming, she said, but charming is a gimmick, “and gimmicks have expiration dates. When people start protesting, and he writes a story about a Holocaust survivor, he won’t look so charming anymore.”

Schneider was proven eerily correct only six months later. In late September 2013, after Israel’s Channel 10 broadcast a series of reports on people leaving Israel because of the high cost of living, Lapid unloaded on his Facebook page:

A word to all those who are “sick of it” and “leaving for Europe.” You happen to have caught me in Budapest. I came here to give a speech against anti-Semitism to parliament and to remind them how they tried to murder my father just because Jews didn’t have their own state, how they killed my grandfather in a concentration camp, how they starved my uncles, how my grandmother was saved at the last minute from a death march. So, sorry if I’m a little impatient toward people who are willing to throw in the trash the only land Jews have because it’s more comfortable in Berlin.

Lapid’s rant might have been sincere, but it got him into serious trouble, mainly because he used the Holocaust as a rhetorical tool. Yes, it’s his family’s story, and yes, he’s expressing his personal feelings, but millions of Israelis have similar stories, and even in notoriously outspoken Israel some things are sacred. Using the Holocaust to scold people who choose to relocate doesn’t go over well. Lapid also forgot that part of being authentic is telling the truth. One need only check his Wikipedia page to discover that Lapid lived in Los Angeles for six years after divorcing his first wife.

It was a serious gaffe, but it seems that Lapid and his team are learning from it. Though it might appear otherwise at times, they are aware of the transition Lapid must make from being a candidate making promises to being a senior minister who must carry them out. In short, they are beginning to understand the limits of social media along with its potential, and the power it gives to citizens as well as candidates. They also understand that the closeness between politicians and their constituents fostered by social media has created a new sense of accountability they must respond to.

Yesh Atid MK Boaz Toporovsky strikes a pose after a long night of voting. Toporovsky quickly deleted the photo from his Facebook page, but was nonetheless subject to much mockery on social media.

Roei Deutsch, CEO of the reputation management firm Veribo, runs Yesh Atid’s social media campaign. He told me that Lapid now “invests time in staying connected with voters and trying to show the work that he’s doing,” insisting that the finance minister still writes all his own posts. The main role of Lapid’s Facebook page has switched to giving out information rather than crafting an image. Part of this transition was the formation of the Yesh Atid Team, which does nothing but respond to questions and comments on Facebook about Lapid and other MKs. Team members post under their own names, without pretending to be the MK in question. “We take questions and comments seriously,” says Deutsch, “and try to go the extra mile.”

Deutsch and his team are undoubtedly working hard, but the transition hasn’t been easy. In particular, the use of social media in a personal way makes it extremely difficult for political parties and their consultants to “control the narrative,” which often leads to unintended consequences.

But Deutsch knows that, in Israel today, it’s also good politics. Israeli politicians, he says, often post on intimate topics because, as he puts it, Israelis “are allergic to bullshit,” and personal politics and the politics of personality are a growing trend. Although Israelis vote for a party rather than a candidate, they are increasingly talking about the party leaders, often by their first names—Bibi, Shelly, Yair, Naftali. In other words, the use of personalized social media is one of the best and most effective ways to garner support from voters.

“People want to know what kind of person” a politician is, says Deutsch,

and what they went through in life, and social media allows that kind of direct connection. People don’t just judge on professional terms, they want to know a politician’s values, how he lives his daily life. The old politics, where a minister would wake up next to a podium, are over. Yesh Atid’s MKs are people, and the public connects to them as people.

The question is, how much of the personal image cultivated by these politicians is actually real, and how much is calculated and controlled like any other kind of public relations?

One indication that it may be at least partially the latter is that, while Yair Lapid certainly composes his own Facebook posts, it is not clear that other Yesh Atid MKs do the same. MK Ruth Calderon, for example, who was a professor of Talmud studies before entering politics, used to post quotes from the Talmud on her Facebook page, but her recent posts are on more traditional political topics. In fact, they are now very similar to those of her colleagues in Yesh Atid and Lapid’s own statements to the press. This raises the issue of whether the party of “real people” is actually telling its MKs what to post.

“Messaging is a basic PR strategy that everyone uses,” Deutsch admits. “Most people ask the same questions on Facebook, so this saves us time by giving that information out.” Nonetheless, Yesh Atid’s social media manager insists that his staff does not filter anything MKs write, saying that he’d rather see a typo than go against the party’s media strategy.

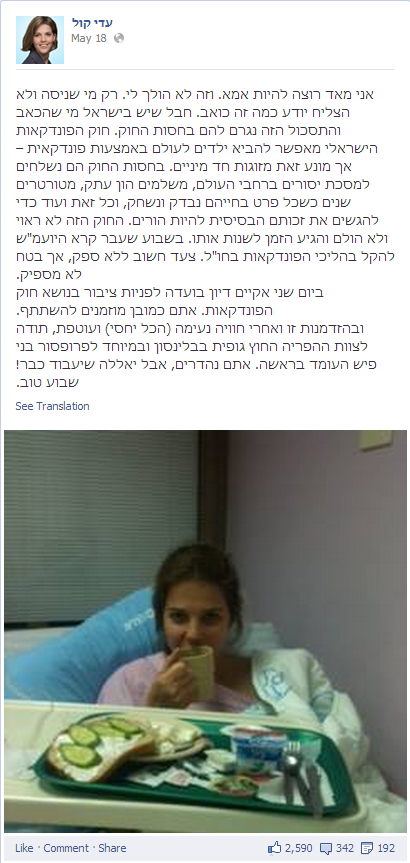

Yesh Atid MK Adi Kol underwent fertility treatments, then posted about it on her Facebook page. Screengrab: Adi Kol / Facebook

Other parties—like Likud, Labor, Bayit Yehudi, and Meretz—are less disciplined than Yesh Atid, and their use of social media reflects this. Some of their MK’s Facebook pages keep to the impersonal American model, but these are usually the least popular. Many other MKs, however, know that looking authentic is a winning strategy in Israel. This also seems to be an approach they choose themselves, rather than being told to adopt it by the party leadership.

The Likud, however, despite being Israel’s ruling party, does not seem to have any social media strategy whatsoever. This shows that, however influential social media has become, it’s still possible to win an Israeli election without a Facebook expert on staff. But this also points to one of the most important aspects of Israel’s social media revolution: It appears to mostly benefit upstart parties like Yesh Atid and Bayit Yehudi, which lack the electoral infrastructure to turn out large numbers of loyal voters.

And this may well prove to be social media’s most important contribution to Israeli democracy. By giving voters a view of the personal lives and characters of their politicians and elected representatives, it has allowed voters to move beyond conventional voting habits to embrace new and possibly better alternatives. While this can be disruptive, it can also be a tremendously revitalizing force, bringing new blood into a political establishment that can easily become alienated from the people it is meant to serve. This is essential to any democracy if it wants to remain vital.

The rise of social media in Israeli politics, then, serves as proof that Israel’s democratic culture, despite many challenges, remains alive and well. Combined with Israeli’s traditional desire for a close, personal relationship with their leaders, it has led directly to the rise of reformist political movements—both Left and Right—who are willing to directly confront some of Israel’s most burning and neglected issues, such as growing economic inequality and the unsustainability of the Haredi draft exemption.

Indeed, it is possible that the use of social media in Israeli politics, and the more vital approach to both campaigning and governance it fosters, could serve as a model for other countries—the United States in particular—whose politics are currently suffering from division and dysfunction. In Israel, social media has helped new and less hidebound political figures and parties rise to power, as well as enabling the Israeli political establishment to finally confront problems that many Israelis believed would never be addressed. This “new politics,” aided by technology and the willingness of both politicians and their constituents to use it in order to achieve a closer and, perhaps, more honest relationship, could well aid the Western democracies in ameliorating some of their current discontents.

![]()

Banner Photo: Courtesy of Yesh Atid