Until his final blog post, Norman Geras dedicated his life to showing that you can be a faithful member of the hard Left without submitting to the temptations of anti-Americanism, anti-Zionism, and anti-Semitism.

When I heard the news that blogger, activist, and political philosopher Norman Geras—known affectionately to all of us as “Norm”—had died on October 18, 2013 at the age of 70, the first thing I thought of was, strangely enough, the day of the September 11 attacks. A native New Yorker, I was far from home when the attacks occurred, and I learned of them from a stranger on a quiet train platform in Hungary. Like many Americans overseas, I was promptly stranded for days, trying to find a way to get back to the United States. I made it as far as London, and was made to wait there indefinitely.

To add insult to injury, I had just been robbed. So there I was, living on limited, borrowed funds, barely enough to pay for the use of Internet kiosks and despondent visits to pubs. During one of these visits, I happened upon a large Englishman slumped in front of a pint. He had a tabloid open to a picture of a radical Muslim, who was demonstrating either against the U.S. or in favor of the attacks. I grimaced and felt forced to say, “I’m from New York.” He gestured toward the guy in the picture and, with a look of bovine malice, replied, “Well, I think he’s got a point.”

Initially, such reactions to the 9/11 atrocity were almost impossible to fathom. It wasn’t so mysterious that people like Osama Bin Laden existed and wanted to kill as many of us as possible. But I did not anticipate the extent to which ostensibly intelligent and rational people expressed the same lazy contempt as that lone Englishman in the pub. I expected that, at least in the Northeastern United States, a clear-eyed understanding would prevail that mass-casualty terrorism by racist fundamentalists is the very opposite of liberal values. Yet over the coming months I felt a stronger and stronger sense of betrayal as so many strove to “contextualize” the attacks and ascribe rational motives to the perpetrators. In my own liberal-Left political milieu and many of its preferred media outlets, such as The Nation, the London Review of Books, and The Guardian, it was easy to find the assertion that because of U.S. malfeasance of some kind—our foreign policy, our exploitation of developing countries and the environment, our support for Arab dictators and the state of Israel, our racism, arrogance and ignorance, etc.—the Al Qaeda hijackers did indeed have “a point.”

So it was with pleasure and not a little relief that I discovered Norm Geras’ blog shortly after the third anniversary of 9/11. It was one of the earliest and most perceptive blogs on the subject of the War on Terror and its intellectual implications, and in the sparest format permissible by web standards—even the name, “normblog,” was rendered with typographical understatement—Norm addressed all of the pernicious phenomena mentioned above.

“For some time,” Norm, himself a lifelong man of the Left, once wrote, “it has been clear beyond reasonable doubt that a wide swath of the liberal-Left has learned nothing, and will learn nothing, from its sorry historical experience in the 20th century.” Noting the apologetics for 9/11 and Islamic terrorism in general spreading among his own political comrades, Norm noted that “There are always Leftists ready to believe that if a movement has some justice to its cause, a progressive component in its program or outlook, it is to be supported. And that means its crimes and deficiencies must be passed over, be silently ignored, or at the very least played down.”

It was precisely these Leftists that Norm would spend the rest of his life criticizing and opposing. Most importantly, he held that such an attitude was, in fact, a betrayal of the Left, that the defamation of America and apologetics for its enemies were inherently illiberal and accompanied by the abandonment of “democratic values.” Indeed, it was Norm who gave one of the most perceptive and incisive descriptions of this troubling phenomenon and its implications. “At best,” he wrote,

you might get some lip service paid to the events of September 11 having been, well, you know, unfortunate—the preliminary ‘yes’ before the soon-to-follow ‘but’…. And then you’d get all the stuff about root causes, deep grievances, the role of U.S. foreign policy in creating these; and a subtext, or indeed text, whose meaning was America’s comeuppance. This was not a discourse worthy of a democratically-committed or principled Left, and the would-be defense of it by its proponents, that they were merely trying to explain and not to excuse what happened, was itself a pathetic excuse.

Both Norm’s intellectual talent and his moral clarity made him a beloved and important figure on what is sometimes called Britain’s “decent Left”—men and women who believe in social-democratic principles and are also consistently anti-totalitarian, opposing tyranny and tyrannical violence whoever commits it. This group includes writers and thinkers like Nick Cohen, David Aaronovitch, Eve Garrard, Oliver Kamm, and Francis Wheen, and serves as a modern analog to the anti-Stalinist New York Intellectuals of the mid-20th century. Much of their energy focused on opposing terror and tyranny arising from radical Islam and its Western apologists.

Norm served as one of the intellectual and political leaders of this informal group. His blog and its considerable influence culminated in his co-authorship of the Euston Manifesto in 2006. The manifesto was a collaboration between around 20 members of the “decent Left,” with Norm as the principal author. It called for a “fresh political alignment” according to 15 categories, including democracy, equality, internationalism, universal human rights, and opposition to tyranny, terrorism, and racism. One of the things that set it apart was its emphasis on anti-Americanism and anti-Semitism as forms of bigotry equally dangerous as others emphasized by the Left. It sought, in other words, to purge progressive thought of its most self-defeating tendencies.

The manifesto was published in the New Statesman, as well as The Guardian’s “Comment Is Free” opinion site, both venerable Left-wing publications. It garnered thousands of signatures, including those of linguist Shalom Lappin, historian Marko Attila Hoare, and political theorist Alan Johnson. A U.S. version followed, entitled “American Liberalism and the Euston Manifesto,” which was signed by hundreds more, including Daniel Bell, Leon Wieseltier, Jeffrey Herf, and Walter Laqueur. The effort established a provocative platform that was much discussed and debated. With typical modesty, Norm simply said that it was “the main political outcome of my blogging and… something I’m happy about.”

It is not surprising to me, and should be surprising to no one, that Norm became such an important and central figure on the “decent Left.” Of all the Virgils who led me through the maze of bewilderment, anger, and alienation caused by the indulgent intellectual reaction to 9/11, Norm always struck me as having a constellation of qualities that made him the ideal advocate for a truly progressive politics. This was the result, I think, of his long and often revelatory intellectual journey.

Norman Myron Geras was born in 1943 in Bulawayo in what was then Southern Rhodesia. He moved to the United Kingdom in 1962 and studied politics, philosophy, and economics at Pembroke College, Oxford, graduating First Class in 1965. Soon after, he married the writer Adèle Geras and the couple moved to Manchester. Norm would spend the rest of his academic career at the University of Manchester, retiring in 2003 as Professor Emeritus of Politics. But few outside the rarefied world of academia know just how significant that career was to the development of late-20th century political thought.

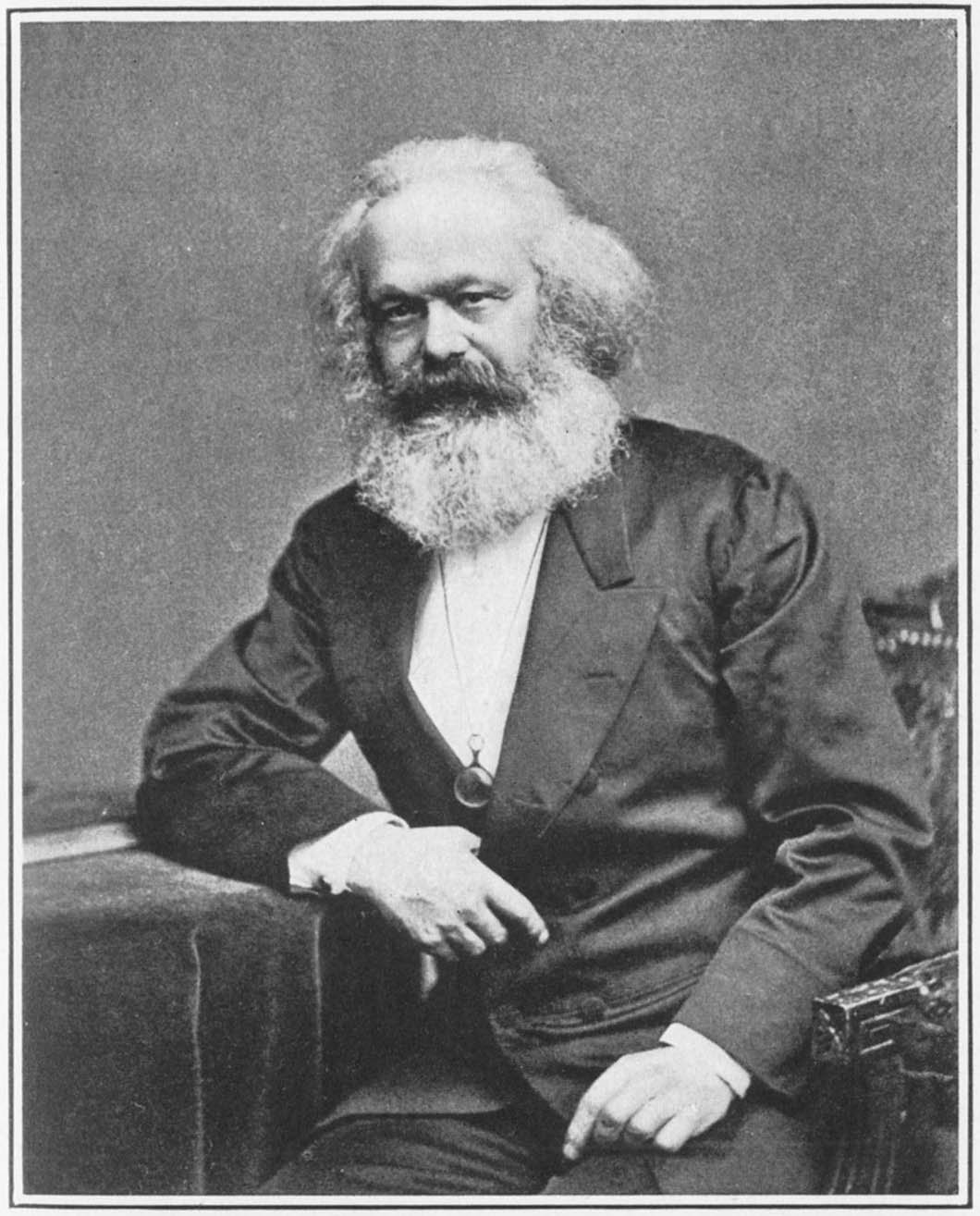

Norm’s scholarly focus was the political philosophy of Karl Marx. His approach was marked by his desire to achieve “standards of clarity, precision, consistency”; something that, along with his lapidary and accessible prose, set him apart from many of his peers. This quality, as well as the diversity of his interests—he loved both historical materialism and cricket equally—was probably how a man of such esoteric concerns eventually wrote a blog that commanded a readership in the thousands.

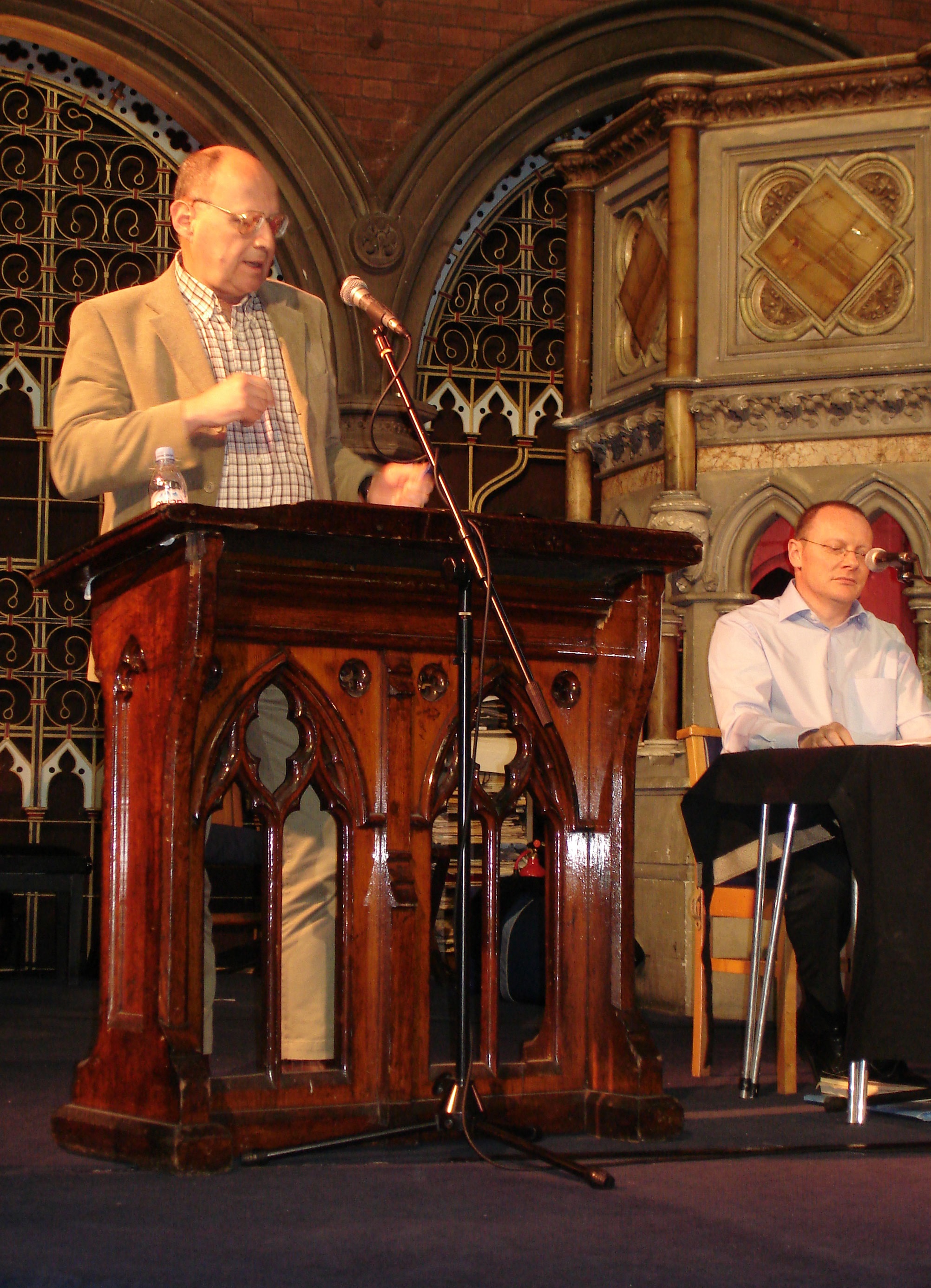

Alan Johnson, Eve Garrard, Nick Cohen, Shalom Lappin and Norman Geras signing the Euston Manifesto. Photo: fys / Wikimedia

In 1983, Norm published his most significant work, a major contribution to Marxist theory called Marx and Human Nature. In it, Norm confronted the “legend” that Marx denied the existence of human nature. Norm argued that human nature did in fact exist, that Marx was well aware of it, and that it was ethically incumbent on socialists to account for it. Concise and argued with a force arising from the straightforward elegance of its prose, the slim volume is now regarded as a canonical work on Marx’s treatment of the topic of “nature versus nurture.”

For Norm, however, this did not entail repudiating Marx. “It is a choice,” he once explained to an interviewer who asked whether he was “still” a Marxist, “to work within a flawed tradition, in the hope of strengthening and adding to it.” But Norm’s theories did have a very beneficial effect. By rejecting the kind of vulgar determinism embraced by many Marxists, according to which every aspect of human life and society is determined solely by economic conditions, Norm saved himself from being forced to shoehorn reality into ideological fantasy. It protected him from the cartoonish morality and conspiracy theory that typifies much of the contemporary Left, and allowed him to make a lucid and cogent response to current events from a Left-wing perspective.

Geras was at the forefront of the “decent Left,” supporting democracy and freedom above all else.

Like any other capable thinker, Norm’s ideas matured over time, and 15 years later, he published The Contract of Mutual Indifference, a major work of political philosophy. The book was inspired by a very unusual circumstance. Norm had found himself on a train, reading a book about the Nazi death camp at Sobibor while on his way to spend the day watching cricket. This “not very appropriate… conjunction,” as he called it, set Norm on the path to considering some of “the implications for modern political thought of a catastrophe of the order of the Holocaust.” He concluded that there was a decidedly dark side to the classic political theories of the “social contract” advanced by such thinkers as Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau. Norm posited that the traditional concept of the social contract involved “a contract of mutual indifference,” in which people reached an unspoken agreement not to care for one another. “To the extent that calamities of this genocidal scope,” he wrote, referring to the Holocaust,

as well as other great and continuing brutalities – the widespread practice of torture, the enslavement of large numbers of young children in labor or prostitution, deep, life-reducing poverty – are countenanced, tolerated, lived with, by millions of people who know about them and do not do anything (much) to stop them, they testify to the reality of [a contract of mutual indifference], as governing most of the inter-relationships between the earth’s inhabitants.

Norm argued, however, that there was a way out of this dark vision of human relations: a “positive duty to give aid,” which he saw as a “reconstructed Marxian ethics of revolution.” It was based on a simple moral proposition: “If you do not come to the aid of others who are under grave assault, in acute danger or crying need, you cannot reasonably expect others to come to your aid in similar emergency; you cannot consider them so obligated to you.”

This became the foundation of Norm’s approach to issues of war and peace. In particular, it led to his support for military intervention in Iraq. It is wrong, he believed, to be a “bystander” to genocide and mass murder. Accordingly, the state that commits crimes against humanity effectively surrenders its sovereignty, and “there is no other moral option than to support the removal of such a regime if a removal is in the offing.”

It is no secret that much of the political Left and the political class in general have been evolving in a very different direction from Norm. He himself described this shift as based on

a thesis about America’s role in the world: the thesis that, as the hegemon of global capitalism, the U.S. government has pursued over many decades a foreign policy of assisting anti-democratic forces and opposing progressive change, and has often done so by lethal means, including terror, for which purpose it has supported proxies of one kind and another.

As in most ideologies, there is an element of truth in this—such as the case of Chile or Nicaragua—but Norm lamented that this thesis had come to “so [dominate] people’s vision that nothing else relevant to the issues can be allowed its due place.” This, he believed, resulted in “a displacement of the Left’s most fundamental values by a misguided strategic choice, namely, opposition to the US, come what may.” In other words, anti-Americanism had stultified the moral intelligence of much of the Left.

After the end of the Cold War, this resulted in a strange and paradoxical alliance between the far-Left and the far-Right. The tendency on the far-Left to ruminate on the unique evil of America found in the nativist isolationism of the far-Right an unlikely complement. When NATO finally engaged in the Yugoslavian wars, the far-Left opposed it as U.S. “imperialism,” while the far-Right echoed the sentiment from its perspective, asking why American lives and money should be spent on helping foreigners in distant places. A consensus on non-interventionism was forged at both ends of the political spectrum.

The post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq made non-interventionism mainstream. Liberal democracies tend to have a shallow appetite for long, bloody, expensive counterinsurgencies, and the wars became increasingly unpopular among the American people. As a result, mainstream liberals began to embrace non-interventionism, and were reinforced by extremists on both the Left and Right. The result was a new embrace of “political realism” by the establishment, a realism that was deeply skeptical of the use of military power and eager to depict America’s most fanatical enemies as viable partners.

Driven by his analysis of the “contract of mutual indifference,” Norm was having none of this. On Afghanistan, Norm applauded the U.S. liberation of the Afghan people “from a vile political and social tyranny, even if only as a byproduct of America’s own objectives.” Similarly, he believed that the world had a positive duty to aid the victims of Saddam Hussein. “Whatever subsidiary reasons could have been—and in fact were—given for the war to get rid of the Saddam Hussein regime,” he wrote,

the most powerful reason in its favor was a simple one: the regime had been responsible for, it was daily adding to, and for all that anyone could reasonably expect, it would go on for the foreseeable future adding to, an immensity of pain and grief, killing, torture and mutilation…. This was not merely an unpleasant tyranny amongst many others—it was one of the very worst of recent times, with the blood of hundreds of thousands of people on its hands.

Norm could not locate a moral case for opposing the intervention, though he allowed that “there were creditable moral reasons for having doubts about the moral case for it.” He saw intervention as an effort to deal with a humanitarian emergency. “The house was on fire,” he wrote of the Hussein regime’s atrocities. “No argument against trying to save the people in the house is worth a fig if it doesn’t accept this fact honestly, and recognize that there is something considerable to be said for indeed trying to save these people.” To Norm, interventionism was not just a necessary foreign policy tool; it was in some cases a moral imperative.

Norm also made a significant and influential stand against another toxic tendency on the left that intensified after 9/11 and the beginning of the War on Terror: anti-Semitism. Indeed, almost from the moment the towers fell, a miasma of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories settled over the incident. Theories like the claim that Israel had foreknowledge of the attacks and failed to warn anyone except “4,000 Israeli workers”—embraced, for example, by erstwhile New Jersey Poet Laureate Amiri Baraka—grew into Lindberghian fantasies of Jewish political influence in America and Britain. They quickly spread into ostensibly reputable organs of the intellectual left. In 2002, for example, the New Statesman investigated the “Zionist lobby” in a cover story illustrated by a Star of David pinned to a Union Jack. In 2004, Kalle Lasn, publisher of the anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters, asked about American neoconservatives, “Why won’t anyone say they’re Jewish?”

Unfortunately, there is a long history of anti-Semitism among revolutionary movements both Left and Right. Indeed, anti-Semitism was once called “the socialism of fools,” referring to the scapegoating of Jews in the name of social justice. Over the course of the 20th century, among the Nazis, the Soviets, and their facsimiles, anti-Semitism often served as an engine of revolution.

Liberals and social democrats often fail to understand this. Heirs to the tradition of Enlightenment rationalism, they often find it difficult to acknowledge the role of the irrational in politics; how anti-Semitism can be used to mobilize a “people of light” against a “people of darkness” in an eschatological end-game. As a result, the liberal democrat often learns about a suicide bombing in Tel Aviv and concludes, not that the bomber was seeking—quite consciously and deliberately—to achieve religious ecstasy through the murder of Jews, but rather that the bomber must have been driven to madness by the occupation of the West Bank. No rational person could do such a thing, this observer believes, unless they had been made insane by oppression.

Norm was painfully aware of all this, and it led him to the tragic realization that “Not much more than 60 years after the Jews of Europe were nearly annihilated… the Jewish state has become an object of special opprobrium,” which, Norm wrote, went well “beyond that criticism which is justified, equitable, applied in equal measure to other nations when it fits.”

Through analysis of Marx’s writings, Geras concluded that there was a moral duty to aid the oppressed.

Disgusted that such critics “could only give out a thin, calculating, morally depleted discourse of ‘contextualization,’” Norm was devastating in his critique, saying that “The root-causers always plead a desire merely to expand our understanding, but they’re very selective in what they want us to ‘understand.’” They empathize with Palestinian terrorists, he wrote, but not “the worries of Israeli and other Jews,” despite “the decades-long hostility of the Arab world to the State of Israel and the teaching of hatred there against Jews” as well as “the acts of war against that state and the acts of terrorism against its citizens.” Although “this would seem to constitute a potentially rich soil of roots and causes,” Israel’s critics appeared remarkably uninterested in them. “A thing held too close to the eye,” Norm once wrote of anti-Americanism, “obstructs the vision.” When applied to Israel, this approach leads to the indulgence of anti-Semitism. Norm referred to several “alibis” proffered by anti-Israel activists and thinkers in order to justify this myopia, such as treating anti-Semitism “as a pure epiphenomenon of the Israel-Palestine conflict.” He cited British film director Ken Loach, who said in March 2009 that if there was a rise of anti-Semitism, “it is perfectly understandable, because Israel feeds feelings of anti-Semitism.” Norm wrote that “the key word here is ‘understandable,’” which means “something along the lines of ‘excusable’ or, at any rate, not an issue to get excited about.”

Norm had little patience for the standard defense that anti-Zionism is not anti-Semitism. “No, it isn’t,” he wrote, “unless it is.” He granted that the two are not necessarily the same, but he rejected the idea that simply announcing the difference grants immunity from charges of racism. “In the outpouring of hatred towards Israel today,” he wrote, “it scarcely matters what part of it is impelled by a pre-existing hostility towards Jews as such and what part by a groundless feeling that the Jewish state is especially vicious among the nations of the world…. Both are forms of anti-Semitism.”

The implications of this were both ominous and deeply sad for Norm, who wrote stoically, “We now know… should a new calamity ever befall the Jewish people, there will be, again, not only the direct architects and executants but also those who collaborate, who collude, who look away and find the words to go with doing so.”

Unfortunately, even now, 12 years after that day in the pub, I find myself constantly faced with reminders of just how relevant Norm and his work remain. To cite one current example, here is Robert Wright in The Atlantic on the subject of negotiations with Iran:

If you’re like the average American, here’s a fact you don’t know: in 1953, the United States sponsored a coup in Iran, overthrowing a democratically elected government and installing a brutally repressive regime that ruled for decades. Iranians, on the other hand, are very aware of this, which helps explain why, to this day, many of them are gravely suspicious of American intentions. It also helps explain the 1979 takeover of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran—an event that many Americans no doubt chalk up to unfathomable religious zealotry.

One wishes Norm were around to criticize the toxic naiveté that removes “religious zealotry” from the causes of the 1979 revolution and Iran’s ultimate takeover by a regime of religious zealots; or the refusal to contend with what Iranian government officials have said about Israel; or the claim, by people like Wright, that genocidal statements by leaders like Mahmoud Ahmedinejad are still considered “disputed.” One wishes Norm were here to note just how many precursors to Wright similarly “contextualized” the Nazis.

And Norm’s unique voice seems equally present in the face of the ongoing efforts of many to portray Israel as a state in which racism is its defining characteristic. Efforts like Leftist journalist Max Blumenthal’s just-published Goliath, which sniggers darkly that Israel is a place where you can learn “How to Kill Goyim and Influence People.” Blumenthal’s blinkered and one-sided conviction that Israel is fundamentally racist, but that Arab and Muslim anti-Semitism is at worst what Norm called an “epiphenomenon of Zionism,” is precisely the sort of thing Norm was so adept at deconstructing and demolishing.

From his simple blog, Geras forcefully denounced the anti-Semitic underpinnings of anti-Zionism.

Losing Norm’s voice isn’t easy. One of the worst things about death is the sense of futility it imparts, a reminder of the truth expressed by the famous quote from the Tao Te Ching: “Heaven and Earth are indifferent, and treat the creatures as straw dogs.” That a voice so important to one’s political development and convictions could be silenced is a hard thing to accept. 9/11 was the great trauma of our generation, and as the response to it began to echo the initial obscenity, for many of us Norm became the moral last helicopter out of Saigon.

In a sense, however, the continuing relevance of Norm’s work, though unfortunate, is also a kind of consolation. He helped us all understand our own inchoate belief that the Left did not have to embrace the political dysfunctions of our era. One did not have to leave the Left in order to remain true to its principles. He was not a neoconservative, though his policy ideas sometimes overlapped with theirs. He was an authentic Marxist who nonetheless saw in liberalism and American values a wellspring of progressive politics. And he understood that American power, including military power, was not inherently evil, but could be a means to achieve ethical outcomes. Today, as the U.S. begins to withdraw from the Middle East and reconsiders critically its conviction that American power carries ethical responsibilities to the rest of the world, it is worth remembering Norm’s admonition that none of us is required—or has a right—to honor a contract of mutual indifference. One hopes that this simple moral imperative will ultimately prove to be his greatest legacy.

![]()

Banner Photo: Adèle Geras