In an uncertain world, Japan rethinks its global posture.

In the early morning of February 1, after months of secret negotiations between the Japanese government and ISIS over the release of two of the terrorist group’s hostages, Haruna Yukawa and Kenji Goto, ISIS released Goto’s execution video, entitled “A Message to the Government of Japan.” Aired on major television networks throughout Japan, the chilling video featured the executioner known as Jihadi John responding to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s decision to send $200 million in humanitarian aid to nations battling ISIS.

To the Japanese government: You, like your foolish allies in the Satanic coalition, have yet to understand that we, by Allah’s grace, are an Islamic Caliphate with authority and power, an entire army thirsty for your blood. Abe, because of your reckless decision to take part in an unwinnable war, this knife will not only slaughter Kenji, but will also carry on and cause carnage wherever your people are found. So let the nightmare for Japan begin.

By the time the video finished by showing what appeared to be a beheaded Goto, an illusion long held by Japanese leaders and ordinary citizens alike was shattered. The unprecedented act of Islamic terrorism against Japan has led to a growing understanding that despite its longstanding security relationship with the United States, Japan remained helpless and vulnerable in the face of a hostage crisis spurred by non-state actors half the world away. And thus, perhaps, even more vulnerable against its increasingly aggressive neighbors.

Since Japan signed the Potsdam Declaration after World War II, its military has been constitutionally prohibited from pursuing offensive operations on behalf of itself or its allies. American security guarantees have ensured Japan’s regional and international safety. But Japan’s essential lack of military and foreign policy autonomy, combined with growing criticism of President Barack Obama’s regional strategies in both the Middle East and East Asia, has raised questions about whether Japan’s 70-year constitutional commitment to pacifism and demilitarization remains wise today.

“This is 9/11 for Japan,” Kunihiko Miyake, a former diplomat who has advised Abe on foreign affairs, told The New York Times shortly after Goto’s murder. “It is time for Japan to stop daydreaming that its good will and noble intentions would be enough to shield it from the dangerous world out there. Americans have faced this harsh reality, the French have faced it, and now we are, too.”

Since the hostage crisis, Abe has vowed to “make terrorists pay the price,” and has referred to the crisis to secure Parliamentary approval to reinterpret Article 9 of the constitution, which prohibits a Japanese military, so that Japan can defend allies as part of “collective defense,” establish a national security council, increase spending to its “Self-Defense Force,” and open up a domestic defense industry. “No country is completely safe from terrorism,” Abe told Parliament the week before Goto’s execution. “How do we cut the influence of ISIL, and put a stop to extremism? Japan must play its part in achieving this.”

The Abe administration’s security bill is currently sitting for approval in the Diet’s upper house; should it pass a final vote, it would give the Japanese military the ability to fight with allies in foreign conflicts for the first time in 70 years. Since the bill’s introduction, massive opposition has uncharacteristically erupted from the Japanese public—56 percent of whom, according to Asahi Shimbun opinion polls, are against militarizing Japan. In July, anti-war protests led by grassroots organizations were attended by 60,000 people, garnering national media attention in front of the Parliament building. In August, 50 former journalists created a coalition to deliver a message from five former Japanese prime ministers demanding that Abe withdraw the bill. Criticism against Abe has even come from within his own party. Liberal Democratic Party member Seiichiro Murakami tearfully and passionately opposed his party’s support for the revisions. “Why are we gambling the fate of the next generation, all the 20 year olds who have a bright future?” Murakami said. “As a human being, I can’t send young people to war.”

Japan’s essential lack of military autonomy, combined with growing criticism of President Obama’s foreign policy strategy, has raised questions about whether Japan’s 70-year commitment to demilitarization remains wise today.

But Abe’s determination to push the legislation despite widespread public dissent indicates that his convictions lie not in what his detractors claim is “warmongering,” but in significant policy concerns regarding Japan’s security in East Asia and abroad. It reflects the tangible threat that the current unequal U.S.-Japan defense relationship poses for Japan’s national security. As China’s military and territorial hegemony over the South China Sea continues to grow, conflict between South and North Korea flares up once again, and American security guarantees to Iraq and Ukraine ring hollow, it is clear that Abe’s ambitions are in response to an unsettling decline in U.S. authority. While the main goal of the legislation is ostensibly to allow Japan to come to the “collective defense” of its allies, it’s not hard to spot Abe’s real concern that allies will fail to come to the collective defense of Japan.

Continuing in the footsteps of his grandfather, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, who fought to make similar revisions during his time in office, Abe seeks to establish Japan as a military power to fill in the vacuum left by the United States. His legacy hinges on his ability to secure Japan’s future as a legitimate, reliable, and independent military player in ensuring regional and international peace. In a rapidly changing East Asia, and an increasingly global world with increasingly global threats, revising archaic definitions of constitutional pacifism are a complicated but necessary response to the current unequal security relationship between the U.S. and Japan.

After its unconditional surrender to the U.S. in 1945, stripped of military capabilities, Japan has had only the U.S. to rely on for national security. Since Article 9 of the largely U.S.-written constitution declared that Japan would never again maintain “land, sea or air forces or other war potential,” a Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security was reached in 1952 to ensure Japan’s safety from foreign threats, stipulating that the U.S. would help defend Japan against external enemies, while a Japanese defense force would handle internal threats and natural disasters.

The treaty allowed the United States to have military bases across Japan in order to preserve regional security. There are currently around 50,000 U.S. military personnel stationed in 23 military bases across Japan. During the Vietnam War, Japanese bases acted as strategic and logistical posts for American troops. More recently, the United States has used the bases to deploy long-distance surveillance drones over China and North Korea. Japan’s constitutional constraints on military action, combined with the pacifist sentiments deriving from the still-anguishing nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, have led to the rejection of any measure that might alter the status quo. And the rhetorical and tangible security commitments that America has made to Japan has warded off threats, leading to 70 years of peace.

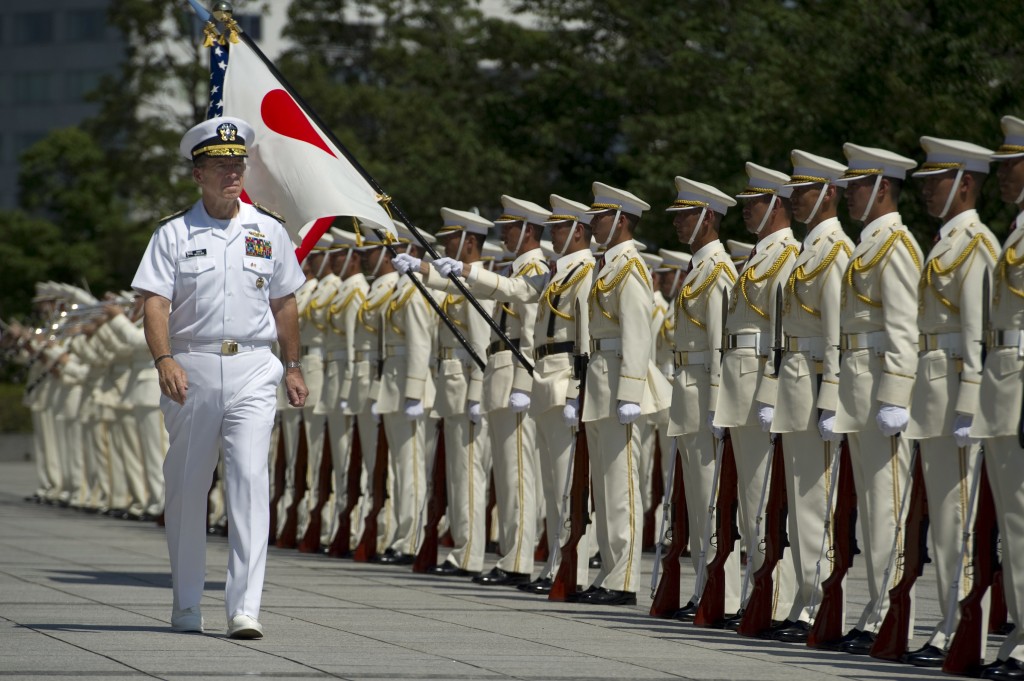

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen reviews Japanese Self-Defense Force troops during a welcoming ceremony at the Ministry of Defense in Tokyo, Japan, July 15, 2011. Photo: Petty Officer 1st Class Chad J. McNeeley / U.S. Navy / Wikimedia

But despite analysts calling the defense relationship a “mutual” one, the U.S.-Japan alliance has always hinged more on support from the U.S. than from Japan. In 1990, the lack of involvement of Japan’s military forces in the Gulf War was widely criticized by the U.S., when Japanese assistance to Kuwait was limited solely to cash because of domestic opposition to military deployment. A decade later, however, Japan deployed 600 soldiers in humanitarian capacities during the Iraq War, a decision that attracted fierce domestic opposition and numerous unsuccessful lawsuits. Sending the first foreign deployment of Japanese troops since World War II to build water purification facilities in Iraq would seem to have little connection to Japan’s self-defense, the only constitutionally acceptable reason for military activity. But as Gavan McCormack, a professor at the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University, wrote in 2004, Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi made his decision not because he supported President George W. Bush’s regional agenda, but because he needed to ensure that the alliance that guaranteed Japan’s security was upheld.

Although the [Bush-Koizumi] relationship is close, that does not necessarily mean that Koizumi, or Japan, really wanted to go to war against Iraq or that it supports the US position on Palestine; for Japan under Koizumi North Korea is the key factor. In February 2004, he declared that it was of overwhelming importance for Japan to show that it was a “trustworthy ally,” because (as he put it) if ever Japan were to come under attack it would be the US, not the UN or any other country, that would come to its aid. When he declared support for the US-led war on Iraq in March 2003, and when he sent Japanese forces to aid the occupation in January 2004, it was not Iraq that was in the Japanese sights so much as North Korea.

Abe’s anti-ISIS rhetoric and actions, combined with his attempt to alter his country’s interpretation of Article 9 despite domestic opposition, parallel the actions and thought processes of his predecessor and fellow party member Koizumi. If Abe succeeds, Japan will be able to more fully support the U.S. in security issues, which would hopefully ensure steadfast U.S. support for Japan’s security.

Abe’s ambitions to establish a domestic defense industry could also be taken as not just a method to strengthen bonds with the U.S, but a representation of his anxiety towards the U.S.’s military commitments. Such an industry would help to assert Japan’s independence in the region, no longer being beholden to a foreign country for security.

As far back as 2000, when he was just a member of the Diet, Abe has raised concerns about the unequal power relationship with the U.S., codified by Japan’s constitutional constraints. Article 51 of the UN Charter details a member nation’s inherent right to practice “collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a member of the United Nations.” As Abe noted, “It is extremely strange to think that we have the right but cannot use it.”

Abe has devoted most of the past decade to move Japan towards becoming a “Western force” with a larger role in global affairs. His historic address to Congress earlier this April, the first ever by a Japanese Prime Minister, showed his desire to strengthen U.S.-Japan ties, while simultaneously asserting Japan’s reputation as a reliable, independent player on the international stage. And after the Diet’s decision to move the bill for consideration, Abe asserted that “These laws are absolutely necessary because the security situation surrounding Japan is growing more severe.”

A missile is launched from the Japanese destroyer JDS Kongo during Japan’s first Aegis missile test. Photo: U.S. Navy / Wikimedia

Abe is right: Japan faces a series of security issues from its neighbors, which has grown at the same time that the U.S. military presence in East Asia has shrunk. Nearly 9,000 Marines are scheduled to be redeployed from Japan to Guam and Hawaii, partially as a cost-cutting measure due to the high cost of living in Japan and partially due to sustained public opposition to the American presence on the island of Okinawa. Sequestration and budget cuts are forcing the U.S. military to, as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Martin Dempsey said while touring a U.S. base in Japan in 2013, “find a way to accomplish the same thing but with smaller force structures.” The effects of this withdrawal have been incorporated into Japanese military policy. A 2014 report issued by the Japanese Ministry of Defense opened by noting that “the patterns of U.S. involvement in the world are changing.” It went on to note that budget cuts have led to “suspension of training, delayed deployment of aircraft carriers, and grounding of air squadrons,” and if those cuts continue, “risks for the U.S. forces posed by shifts in the security environment would grow significantly.”

The move to militarize Japan is therefore supported by the U.S., UCLA associate professor of history Katsuya Hirano told me, because America “is now trying to reduce the size of its military operation due largely to its weakening economic status. The U.S. wants Japan to have a more visible military presence in the Asia-Pacific region, especially against China and North Korea.” Indeed, with growing military aggression from China, renewed military tension between South and North Korea, the ever-present North Korea’s nuclear threat, and further Russian military development on the Kuril Islands, Japan faces questions of U.S. military authority in a new East Asian power dynamic where neither the U.S. nor Japan is on top. That spot is now taken by China.

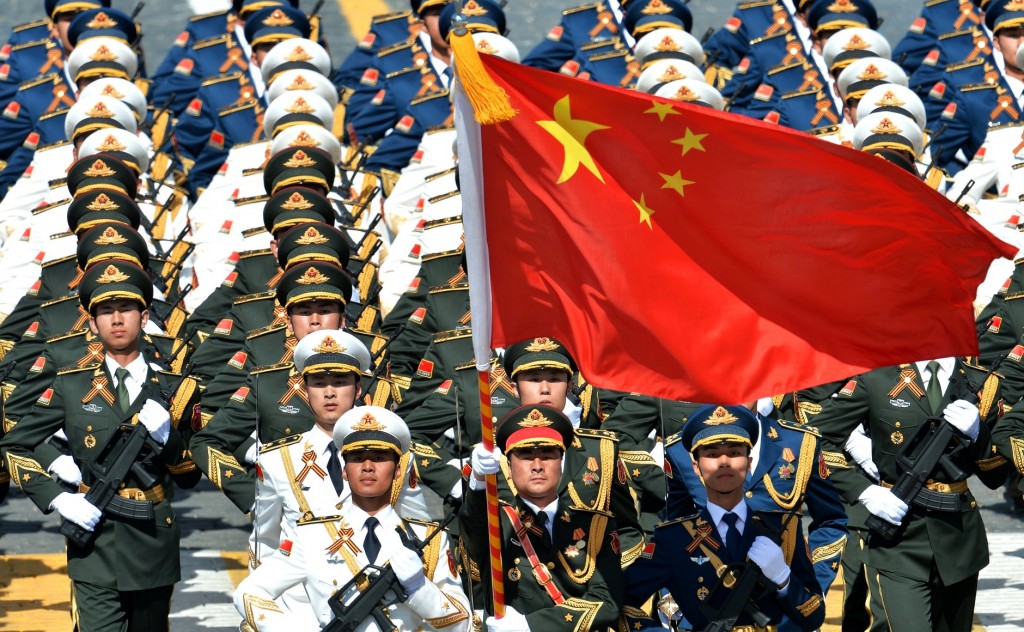

Napoleon Bonaparte supposedly once said of China, “Let her sleep, for when she wakes she will shake the world.” His warning proved to be right. Led by nationalist President Xi Jinping, who took over in 2013, China has grown to become the second-biggest military spender in the world. In 2015, it announced that it was boosting its defense budget more than ten percent to $145 billion, almost three times larger than that of Japan’s Self-Defense Force. While the growth of China’s military capabilities can be attributed largely to its economic growth, what truly worries Japanese leaders is China’s increasingly powerful nationalist movement. These sentiments have been indoctrinated into the population by a 20-year “patriotic education” campaign that asserts China’s right to dominate East Asia and vilifies Japan’s “evil” actions during its colonial rule. The atrocities of Japanese colonialism have been used to justify the defense budget increase; as one Chinese official was quoted in Foreign Affairs, “Our lesson from history—those who fall behind will get bullied—this is something we will never forget.” Perhaps what epitomizes the Chinese quest for supremacy in the region is the September 3 Beijing military parade, which will be led by 12,000 troops, celebrating China’s victory over Japan in World War II. Xi’s “Chinese Dream” extends far beyond “rich nation, strong army,” as is popularly said. China is committed and determined to modernize and improve its military to usurp U.S. control over East Asia. Backed up by a nationalist-supremacist ideology reminiscent of Imperial Japan, China’s aggressive military policies seek not regional security but regional dominance.

A contingent from China’s People’s Liberation Army marches at the Moscow Victory Day Parade, May 9 2015. Photo: Presidential Press and Information Office / Wikimedia

This problem is exacerbated by a decline in American regional hegemony. As Adm. Samuel J. Locklear, the commander of U.S. Pacific Command, admitted at a naval conference last year, “Our historic dominance, that most of us in this room have enjoyed, is diminishing. No question. So let me say it again. Our historic dominance, that most of us in our careers have enjoyed, is diminishing.” Trey Obering, the former director of the Missile Defense Agency, argued in a speech this August that China was strategically challenging all foundations of U.S. power in East Asia: “I believe that China is challenging the United States, specifically targeting our strategic ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities], our power projection capabilities, and our technological advantages with their missile programs.”

Indeed, it was discovered two years ago that Beijing had developed a medium-range ship missile that, as Obering said, was designed “clearly and specifically” to target U.S. carrier battle groups. And earlier this year, China successfully created a Wu-14 hypersonic vehicle, which can deliver nuclear warheads while flying ten times the speed of sound. This is to say nothing of China’s cyberwarfare capabilities: In 2014, Senate Armed Service Committee investigators officially found China’s military to be responsible for nine cyberattacks on civilian transportation companies, spreading malware onto airline computers and effectively stealing confidential information. The NSA has accused China of more than 600 hacks of corporate, private, or government entities. And China is widely accused of having perpetrating the hacking of the Office of Personnel Management, accessing the records of over 18 million people. The threat of Chinese hacking affects Japan too: the National Institute of Information Communications Technology said that Japan experienced more than ten billion hacking attempts from China in 2014 alone.

Marines from China’s People’s Liberation Army stand at attention. Photo: Lance Cpl. J.J. Harper / U.S. Marine Corps / Wikimedia

In almost all occasions, China’s military actions have shown a blatant disregard for foreign powers and international law. “China does not acknowledge freedom of navigation and overflight for foreign militaries, while at the same time it is threatening other countries’ territorial waters and airspace. Unless China respects international law and rules, these crises will continue,” Tetsuo Kotani, a senior fellow at the Japanese Institute of International Affairs, told The Guardian this January. On almost all fronts, China’s military is beginning to assert dominance over the U.S., disregarding America’s history of regional authority. Japanese journalist Hidaka Yoshiki, currently a visiting senior fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington D.C., wrote an essay in the Japanese monthly Voice in 2013, as the negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program were ongoing. Titling his article “The Day that the Weak-Hipped Obama Administration Bows to North Korea,” Yoshiki argued that as the number of U.S. forces in Japan decreases, Japan should be concerned with the Obama administration’s seeming lack of interest in Japanese security. “While Obama has continuously stated that he is making the ‘big turn to Asia,’ there is no reality nor substance to his statement…Even currently the number of U.S. troops is decreasing…this phenomenon can be attributed to mostly the decreasing U.S. defense interests in Asia.” As China grows increasingly defiant, it is becoming clear that the U.S. is losing its grip over East Asia.

In response, Japan announced its biggest defense budget ever in January, totaling $42 billion – the third straight year of budget increases after more than a decade of cuts. Jun Okumura, a scholar at the Meiji Institute for Global Affairs in Tokyo, told The Guardian that while the budget increases were partly due to concern over increased North Korean belligerency, they were largely in response to China’s dominance: “China’s increasingly assertive behavior in the East China Sea and air space, plus, of course, its overtly hostile actions against the Philippines and Vietnam certainly have a major influence on the direction of Japan’s military spending, the thrust of its military doctrine and its approach to security alliances.”

A Japanese F-2 jet lands in Guam as part of a training exercise. Photo: Airman 1st Class Courtney Witt / U.S. Air Force / Wikimedia

The increase in the military budget – allowing the purchase of surveillance technology and aircraft, F-35 fighter jets, drones, radar-equipped destroyers, and a missile defense system – is a necessary response to current growing tensions not just with China, but also Russia, whose annexation of Crimea has endured despite Western security guarantees to Ukraine. Abe traveled to Kiev on June 6 to announce that Japan would provide Ukraine with $1.5 billion in credit guarantees and a $1.1 billion development loan. Three days later, perhaps emboldened by American inaction and perhaps piqued by Abe’s announcement, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced plans to accelerate military construction on the disputed Southern Chishima islands, which the Soviet Union seized from Japan at the end of World War II. Japanese anxiety over Russian buildups in the north is exacerbated by increasingly aggressive Chinese designs over the disputed Senkaku islands in the south.

Domestic discussions of Japan’s security have also been concerned with North Korea’s military and nuclear capabilities. The 1994 U.S.-brokered nuclear deal with North Korea – coordinated on the American side by Wendy Sherman, who would later serve as chief nuclear negotiator with Iran – fell apart in 2002 after confessions from Pakistan and Libya that North Korea was secretly continuing nuclear enrichment in violation of the deal. Six-party talks, which included Japan, were unsuccessful in persuading North Korea to dismantle its nuclear weapons program. Since then, Pyongyang has admitted to administering plutonium device tests, banned International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors from conducting inspections, and fired multiple ballistic missiles into the Sea of Japan.

In April 2009, at the beginning of his presidency, Obama struck a chord with many Japanese nationals when he made a speech in Prague stating his commitment to creating a world free of nuclear weaponry.

As the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act. The United States will take concrete steps towards a world without nuclear weapons.

The fact that North Korea had launched a rocket over Japan earlier that same morning made the speech all the more powerful or all the more empty, depending on your point of view. Since then, many have raised questions about whether U.S. foreign diplomacy really has Japan’s security interests in mind. Chief amongst those critics is Yoshiki, who saved his harshest rhetoric for the U.S.’s failure to eliminate North Korea’s nuclear capabilities, leading him in light of the Iran deal to question whether the U.S. could be trusted to ensure Japan’s security.

As I have criticized before, President Obama has barely been in contact with North Korea for four years. The bitter truth is, he has no clue of how to stop North Korea’s nuclear weaponry. And it’s not just North Korea that he has no clue about, it’s Asia as a whole…The fact that Obama is has thrown the North Korean nuclear weapon problem at China just shows fundamentally that he has no idea nor strategy when it comes to diplomacy in Asia.

In 2013, Pyongyang threatened that if Japan dared to try to stop a missile attack directed towards it, it would be seen as “provocative” of war, leading to Tokyo being “consumed in nuclear flames.” “Japan is always in the cross-hairs of our revolutionary army and if Japan makes a slightest move, the spark of war will touch Japan first,” the Korean Central News Agency declared. That same year, the Pentagon uncovered evidence that North Korea had been able to miniaturize a nuclear warhead onto a ballistic missile. As tensions rise once again between North and South Korea, the possibilities of further warfare within the region must factor into the discussion of revising Japan’s peace constitution to create an insurance policy should conflict break out. In light of North Korea’s unpredictability, as well as China’s increased aggression despite the U.S.’s supposed military dominance in East Asia (not to mention Russia’s brazen snubbing of international law without major consequence in Europe, and Syria’s unpunished violation of “red lines” and ISIS’s continued rampages in the Middle East), there is a nagging question on everyone’s minds: does the U.S. truly have Japan’s back?

This is the context in which the debate over Japan’s constitution is being waged. Japanese liberals argue that a revision of the constitution is will not only end Japan’s pacifist policies but is an affront to democracy itself, while conservatives argue, as Abe said, that the bills “are not for engaging in war,” but to “prevent war” by establishing a truly sovereign defense force.

There is a crucial difference between the two arguments. Abe’s detractors, such as the grassroots organization Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy, are looking at the past, when Imperial Japan’s military posed a humanitarian threat to East Asia. They argue that the military should never again be implemented in this way. In contrast, supporters of Abe’s security bill are looking at East Asian policy concerns in the present and the future. The domestic politics of Japan today would simply not allow for Japan’s military to start an offensive war, draft Japanese youth for battle, or repeat the mistakes of the past. These are claims based on unfounded fears.

The security bill will allow for Japan to deploy foreign military forces only if Japan or a close ally is attacked, and if not doing so would threaten Japan’s survival and pose a clear danger to its people. The bill also specifically states that Japan is allowed to deploy armed forces only if there is no other appropriate means available to repel an attack. Looking at the bill within the context of security concerns in East Asia today, one can see that it is designed to ensure regional peace, and further assert Japan’s historic pacifism, rather than endangering it.

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer JDS Kongo sails in formation with other JMSDF ships. Photo: Todd Cichonowicz / U.S. Navy / Wikimedia

There are good reasons that Abe is an unpopular figure: he has repeatedly attempted to downplay Japan’s war crimes during the occupation, he argued in 2007 that Korean comfort women were not forced into sex slavery, and his recent public apology for war-era crimes was deemed by many as “insincere.” But Abe’s concerns – that Japan’s security is inadequate while its borders are being violated, its citizens are under terrorist threat, and U.S. military hegemony is weakening—are real and valid.

Yusuke Takahashi, the Washington correspondent for the public broadcaster NHK, said during a television segment titled “The Threat of Terror in the World? In Japan?” that ISIS’s awareness of Japan’s inability to conduct military action in the Middle East is what made the country vulnerable.

What’s often misunderstood is that it isn’t just military action that made makes a country a target. Last September, America released a list of 60 coalition partners that have committed themselves to fight ISIS and among them is Japan. It is understood that Japan will only engage in humanitarian causes, and not militarily. ISIS wasn’t under a misunderstanding of Japan’s policies in the Middle East, they knew we couldn’t engage militarily. I believe it is under this understanding that [ISIS] was taunting us.

Under current conditions – in Tokyo, Washington, Beijing, Pyongyang, Moscow, Raqqa, and beyond – it is not only ISIS that can taunt, harm, or attack Japan. As former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama prophetically said before he left office, “Someday, the time will come when Japan’s peace will have to be ensured by the Japanese people themselves.” That time has finally come. Abe is adapting policy to adjust to a growing realization: as the world evolves, Japan must too.

![]()

Banner Photo: U.S. Department of Defense / Wikimedia