A leader who embodied Israel’s contradictions as well as its dreams, Sharon absorbed the slings and arrows and gained a nation’s reverence.

I am Auda Abu-Tayi! I carry 23 great wounds, all got in battle. Seventy-five men have I killed with my own hands in battle. I scatter, I burn my enemies’ tents. I take away their flocks and herds. The Turks pay me a golden treasure. Yet I am poor, because I am a river to my people!

—Anthony Quinn as Auda Abu-Tayi, Lawrence of Arabia

“Tell us something people don’t know about you.”

“I love romantic movies.”

— Ariel Sharon in an interview with Yair Lapid, TV personality and now Minister of Finance

The passage of Ariel Sharon—soldier, general, politician, and former Prime Minister of Israel—is upon us at long last. Israelis are saying their final goodbye to one of their country’s most enigmatic, controversial, and ultimately beloved leaders.

The end of Ariel Sharon is the symbolic end of a generation. A generation of men and women who knew a world without a Jewish state, and fought on the battlefield and in the political arena to establish it; who in its service endured the love and hatred of many; and are now swiftly passing, as they must, from the world. A generation of lions for a people who had for so long been lambs.

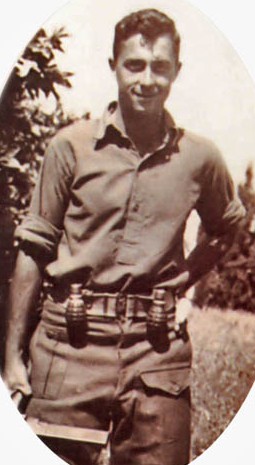

Ariel Sharon, as a

19-year old fighter in the

Haganah, February 1948. Photo:

Tamar Yardeni / Wikimedia

Yet, in many ways, Sharon was the most unlikely of all Israel’s leaders.

For most of his career, Sharon seemed to be Israel’s blunt instrument. He lacked Ben-Gurion’s fervor, Begin’s charismatic eloquence, Golda’s feminist appeal, and Rabin’s coldly incisive mind. Sharon represented the stubborn strength of a people unbowed; the unstoppable force and the immovable object; a sturdy, rumpled bear of a man with a knife between his teeth.

In his final years, however, as he rose to power during one of Israel’s greatest crises, he became something altogether different: A protective elder, a wise tribal chief, and a wise, sentimental grandfather, again ready to make tough sacrifices to protect the Jewish people.

The rough-and-tumble warrior transformed into protector, sympathetic, even lovable; and almost all agreed that, in the hour of trouble, there was no one better to turn to.

Sharon’s long career embodied the contradictions of his public image. Throughout his life, he was a hero, a tragic villain, and then a hero; electable, unelectable, and then electable; triumphant, defeated, and then triumphant. Loved, reviled and then loved again, ultimately leaving a legacy of peace making girded by strength, and ushering in an unprecedented era of prosperity and security for the people of Israel.

He earned all of it over the course of his life. Ariel Sharon was born in 1928 on a moshav to a taciturn and stoic father he later said he never really knew. He fought in the War of Independence, coming out of the famed Battle of Latrun badly wounded. Following the war, he became something like the man-at-arms to then-Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion—a fearless, unpredictable, and headstrong soldier, who cared deeply for his men but did not always follow orders to the letter. He founded Israel’s famed Unit 101, which fought against Palestinian terrorism during the 1950s and would set the operational standard for Israel’s legendary paratrooper units. He was also, at times, more than a bit of a headache. After one particularly bloody engagement, Ben-Gurion asked him how the operation had gone. “OK,” said the young commando. “Too OK,” Ben-Gurion replied.

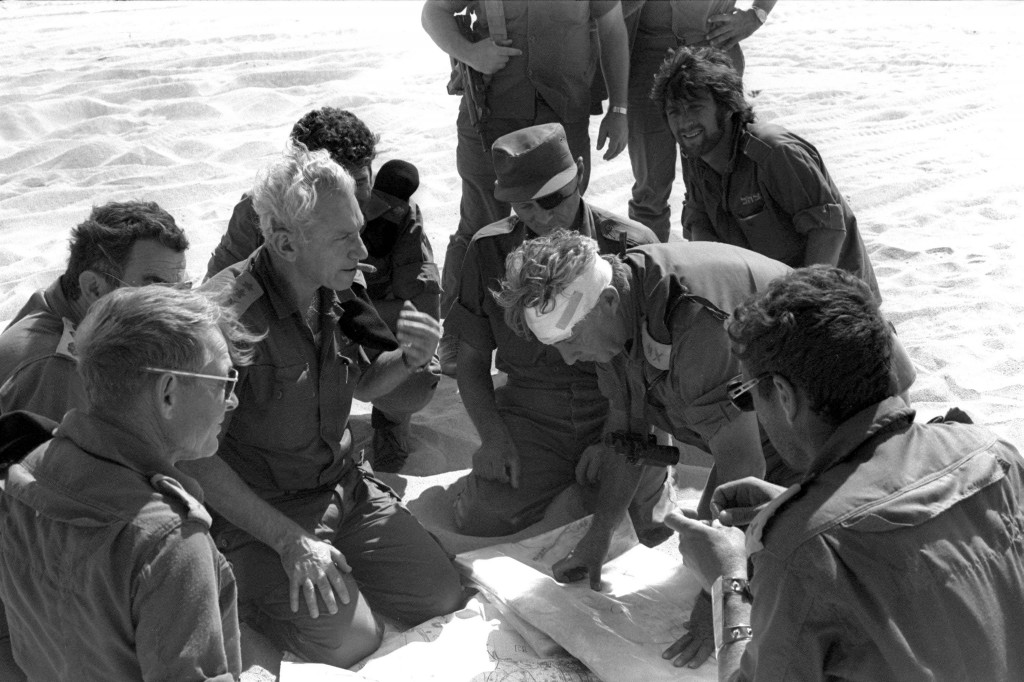

This combination of military prowess and a self-confidence some saw as insubordination would haunt Sharon all his life. Though he did not share in the heroic status generals like Dayan and Rabin enjoyed after the Six Day War of 1967, he came out of the 1973 Yom Kippur War as both a national hero and a fierce critic of the political and military establishment. The tank battles he led in the Sinai—sometimes exceeding his orders—are now studied as tactical masterpieces. And it was he who, sporting a bandage wrapped around his head, saw a gap between the two Egyptian armies in the Sinai, made a bee-line to the Suez Canal with tanks and pontoon bridges, crossed the Canal, and then cut off the entire Egyptian Third Army, effectively winning the Egyptian front. And it was this same Sharon who later oversaw Israel’s withdrawal from the Sinai desert, and the removal of Jewish communities built there, in return for peace with Egypt under the Camp David Accords.

Major General Ariel Sharon talks with David Ben-Gurion during a bus ride along the Israeli Army positions on the Egyptian border. Photo: Israel Defense Forces /Flash90

But following the 1973 war, Sharon also broke the taboo on criticizing the army and the Labor establishment when he denounced the conduct of the early days of the conflict as a disgrace that needlessly sacrificed lives and equipment. Others such as Rabin—with whom Sharon maintained a fraught but lasting friendship—emerged relatively unscathed from the war’s failures, but Sharon was nearly alone in becoming an object of adoration. For a moment, he was almost universally loved.

It didn’t last. Sharon’s entrance into politics following his retirement from the IDF marked the moment he was cast as a polarizing figure. Beginning in the mid-1970s, he left the dominant Labor party, helped Menachem Begin form the Likud, left and formed his own party, then rejoined the Likud when the 1977 elections broke Labor’s decades-long hold on power. It was here that Sharon began to emerge as a major political voice, eventually becoming defense minister, and ultimately presiding over the First Lebanon War.

That war proved a turning point in Sharon’s career, shattering his authority and leaving him in the political wilderness. As defense minister, he was the war’s primary author and its guiding force as the Jewish state sought to secure its northern border from unremitting terrorism. Yet in carrying out his plans, he exceeded his authority and—according to some—manipulated Menachem Begin into expanding the war well beyond its initial parameters. But it was the massacre of over 800 Palestinians at the Sabra and Shatilla refugee camps by Christian Phalangists that proved Sharon’s undoing. The slaughter was the work of a Lebanese militia allied with Israel; a horrifying act of vengeance that defined the sectarian tit-for-tat slaughter of Lebanon’s civil war. A national commission of inquiry, headed by Supreme Court President Yitzhak Kahan, concluded that Sharon should have known a massacre was possible, and thus bore indirect responsibility for it. He was unceremoniously removed from office. For years, Sharon blamed the outcome on Begin; who had, he believed, thrown him to the proverbial wolves.

Haim Bar-Lev (center left), Moshe Dayan (with eyepatch), and Ariel Sharon (with head bandage) consult plans during the Yom Kippur War. Photo: Yossi Greenberg / GPO / Flash90

For nearly two decades after, Sharon was consigned to the political wilderness. Despised by the international community, and considered unelectable to higher office by Israelis across the political spectrum, Sharon appeared to be, for all intents and purposes, finished; a lumbering dinosaur no longer suited to the modern landscape.

Then came the Oslo Accords, their ultimate collapse, and the Palestinian terror campaign of the second intifada. Sharon was initially blamed for the explosion of bloodshed because of his visit to the Temple Mount in 2000, but today we know that Arafat had long been stockpiling weapons, training terrorists, and seeking a pretext for a campaign of mass murder. Having rejected peace at Camp David, and later at Taba, Arafat turned to violence and mass murder as a response to Israel’s extended hand and sweeping offers for peace. To many Israelis, it seemed clear that the Palestinian leadership had deliberately chosen war over peace, once again.

Indeed, for the most part, it was the second intifada that re-made Sharon, not Sharon who made the intifada. Faced with Arafat’s “no” to peace and the horrors of a wave of suicide bombings, and unable to stop the incessant terror attacks under the government of Ehud Barak, Israelis turned to the most reliable security authority they knew, and in 2001, elected Sharon prime minister in a landslide.

It was another decisive turning point. Over the next six years, Sharon would distinguish himself as a tough but also surprisingly moderate leader, showing little of the hardheaded, hard-line nature that had marked earlier stages of his career. He waited a few months before launching Operation Defensive Shield in April 2002, carefully maintaining both the alliance with the United States and Israeli national unity. He showed a deftness of political tactics no less impressive than as a military leader. Ultimately he broke with his own party, founding the Kadima party in order to effect a withdrawal from the Gaza settlements he helped construct.

He also became, for the second time in his career, a consensus figure. In the wake of the failures of Oslo and the Second Intifada, on the one hand, and the settlement movement’s loss of appeal after the Rabin assassination, on the other, Israelis had begun abandoning the extremes and looking for a trustworthy leader in the middle of the map; Sharon’s new party fit perfectly. To many Israelis, he was becoming comforting and parental; a grandfatherly patriarch whose one concern was the protection of his clan; an old man who had suffered deep tragedy—the death of a son and then a wife—and borne it with quiet stoicism; a relic, in many ways, of the old moshavnik Israel that had somehow survived into the new. And indeed, as the man once again in charge, Sharon deserves due credit for defeating the second intifada, bringing terror to heel, and giving Israelis a sense of stability and security unlike any leader after Ben-Gurion.

Sharon was also, of course, throughout his life widely criticized, often harshly so. Indeed, few recent politicians have been as ferociously assailed by so many. The opprobrium directed his way was sometimes fair, but just as often based on lies, and notable for its sputtering venom, which at times bordered on the unhinged.

The hatred came from both inside and outside Israel. Certainly, the Israeli Left despised Sharon early and often. To them, he was both a political and aesthetic nightmare: Patron of the settlements the Labor party had initiated, traitor to the Labor establishment of which he was once a fixture, private landowner and capitalist, and a partisan of military force, he seemed the personification of the new, post-utopian Israel less focused on the kibbutznik dream of collectivism, rooted more in the survival of the Jewish State in the modern Middle East. Even his enormous girth appeared to indicate a man of vast and vulgar appetites, indifferent to the ideas of austerity and equality that had defined Israel’s early years. It was only at the end of Sharon’s career, when his more moderate image and dovish withdrawal from Gaza forced a reconsideration, that the ire finally subsided.

In the international realm, it never receded. They hated him, openly and freely; and they still hate him. He was, in effect, a totem, an effigy, a symbol of the Israel that the European and American political and media establishments felt entitled to demonize. And indeed, to them, Sharon was little less than the devil: A warmonger, a war criminal, a thug, a mass murderer, and—in one transcendently racist cartoon in Britain’s Independent—an eater of babies. The outrageous, often anti-Semitic, attacks knew few bounds.

Agriculture Minister Ariel Sharon meets with Prime Minister Menachem Begin at the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem, August 9, 1977. Photo: Israel Government Press Office / Wikimedia

But this also constituted some of his appeal to Israeli voters. Indeed, Sharon seemed, at times, to be Israel’s iron wall, absorbing the entire world’s loathing on his country’s behalf; bearing it all without complaint, noting only that the thing he most feared was sinat hinam, the “baseless hatred” that the Sages claimed destroyed the Second Temple. “The whole world is against us,” Israelis often say, and they could not help noticing that, more than anyone else, it was against Sharon. He was hated, in effect, for all of us.

At this moment, however, it is difficult to think of anything other than the missed opportunity his passing represents. At the time of his stroke in early 2006, Sharon was headed for another landslide victory as leader of his own Kadima party. He had already carried out the withdrawal from Gaza, and there were indications that another withdrawal from portions of the West Bank was in the works. He had divested himself of the far-Right and pro-settlement elements in the Likud, and his enormous electoral support ensured that he was beholden to very few.

What he could have accomplished had he remained with us is painful to contemplate. He could well have completed the political realignment that began with his election, and forged a new consensus behind the kind of powerful centrist party Israelis have long sought to create without success. It seemed at the time that Sharon was indeed Israel’s De Gaulle, and something like that other aging general’s Gaullist movement—a synthesis of the best elements of both Left and Right—might be in the offing. But it was not to be.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is secure in office, but commands nothing like the consensus enjoyed by Sharon. The old Left-Right divide is indeed over, but Israel remains bitterly split between political and ideological camps. Indeed, with Sharon’s passing, it seems that Israel’s politics did not so much re-divide as shatter into a thousand pieces.

Perhaps all this is wishful thinking. Perhaps even if Sharon had not collapsed, the divisions and disagreements in both Israeli and Palestinian society would have proven too great to overcome to produce a lasting peace. But as the man fades at long last, one is forced to recollect the eight years he spent in a fathomless state, clinging to life, and perhaps even to a shred of his consciousness.

If Arik Sharon was anything, he was strong and he was survivor; and in this sense, he was indeed the personification of his people: Our stubborn insistence, our seemingly infinite capacity to endure, and the strength we may find inside ourselves even in the face of enemies seemingly so much larger and stronger than us.

“Man,” the Greek poet Pindar once wrote, “is but a shadow’s dream.” Ariel Sharon casts a long shadow indeed, and Israel will long live under it, dreaming of what might have been and what can still be.

![]()

Banner Photo: Sharon Perry / Flash90