Lihi Lapid wants women to know that career is a process, reinvention is possible, and the first lesson in life is how much is really out of your hands.

Jewish women are not shy about giving advice. In the 2013 U.S. bestseller, Lean In, Jewish author Sheryl Sandberg tells women they are in charge of their own destinies in the workplace. The only thing holding them back is themselves. She advises young women to put in more time, work harder, and be more committed to their professional development. “Women,” she says, “are hindered by barriers that exist within ourselves.”And only women, according to Sandberg, can solve the problems of getting more women into positions of power and striking the all-important balance between work and family.

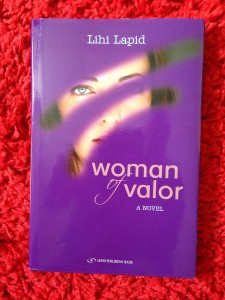

Jewish women give advice in Israel too, but their bestsellers may have a different message. Lihi Lapid, columnist at the newspaper Yediot Aharonot for ten years and wife of current Israeli Finance Minister Yair Lapid, is the author of Woman of Valor, her first book to be translated into English (Gefen, 2013). It deals with many of the same issues as Sandberg’s book, particularly the challenges faced by modern women. But the message of Lapid’s book is very different from Sandberg’s.

Sandberg’s message is that women are in charge of their lives. She tells her readers “internal obstacles deserve a lot more attention, in part because they are under our control.” Lapid, by contrast, speaks about lack of control. Sandberg opens with a story about how Google had no designated parking spots for pregnant women while she was working there. Lapid opens with a story about being confined to bed during the last six months of her pregnancy. Indeed, Sandberg’s unmitigated cheer and celebration of control contrast powerfully with Lapid’s unblinking honesty and endorsement of embracing others in the face of the uncontrollable. These qualities give the book a particularly Israeli character, showing the collective nature of Israeli culture, and its ability to resist the temptation of false optimism.

Woman of Valor has an unusual structure, in that the story of the nameless narrator is told as a fairy tale written by a “princess” about her “prince” husband and their children, the “heir” and the “heiress.” The narrative is then intercut with real letters sent to Lapid by readers of her columns. This underlines the importance Lapid places on letting her readers know that, as one reader Daphna puts it, “My little worries are those of every mother, wife, and woman. As special as I am, I’m just like everyone else. There is something comforting and at the same time diminishing in this recognition.”

Lapid’s project, in other words, begins with the full-on acknowledgement of the difficulty of marriage, motherhood, and career. Indeed, the protagonist admits to bouts of depression and floats the idea of a temporary separation from her husband, as well as coping with a special-needs child and the major career shift from that of a photojournalist who had a gallery show at the age of 26 to a writer who works in her basement next to the washing machine.

At one point in Sandberg’s book, the author brags about once asking television journalist Tom Brokaw how she could have done better in their interview. Brokaw tells her she is only the second person in his entire career to ask for feedback. By contrast, Lapid’s unvarnished assessment of women’s lives implies that one should not be constantly asking how to do things better. Instead, the most important thing one can learn is how to have “moments of happiness” by acknowledging certain unavoidable realities.

One of the most important of these is the fact that there are moments in life when “leaning in” still leaves many factors out of one’s control. In a statement Sandberg would never condone, Lapid writes that she had mistakenly “thought if I only tried hard enough, I’d succeed. Because I’d been told, my entire life, that it depended only on me.”

She learned the hard way how limited such a view can be. Until her first pregnancy, Lapid’s life seemed to prove that “leaning in” works. In a recent interview with Haaretz, Lapid said that when she joined the IDF photo corps, she was handed a bag containing 20 kilos of photography equipment and asked whether she could pick it up and run with it. Lapid responded, “Did you ask any of the men you interviewed for this job the same question? Because if you didn’t, I’m not going to answer it.” She got the job.

On Thursday, October 13, 1994, the family of soldier Nahshon Wachsman, who had been kidnapped and held captive by Hamas, held a prayer vigil at the Western Wall attended by over 100,000 people. Of all the photographers from international news agencies who were present at the event, Lapid was the only woman, and thus the only one who managed to photograph Wachsman’s mother Esther praying in the women’s section of the Wall. The shots were published by news agencies around the world.

When I interviewed Lapid on her recent book tour of the United States, she excitedly recounted how “everyone wanted the pictures” she had taken of the soldier’s mother. The Wachsman photos came to signify Lapid’s persona as a young photographer ready and willing to go anywhere and do anything to get the shot everybody wanted.

But Woman of Valor presents a much more complicated reality. The book opens with an account of Lapid’s experience covering the genocide in Rwanda, where she witnessed the horrors of the warring Hutus and Tutsis. “I tried to hide behind the camera,” she writes, “struggling to maintain sanity in the presence of all the inconceivable pain and sorrow, death, helplessness, and doom.” When Lapid discovered an abandoned boy she guessed to be no more than two years old, she decided to adopt him and take him back to Israel with her. She telephoned her husband to let him know. At first there was silence, then he told her he would “stand by my side no matter what I decided.” Ultimately, she was not permitted to take the child, since his parents’ deaths had not been confirmed, and there was a possibility they would return.

Lapid’s time in Rwanda changed her profoundly, tempering her zest for photography and awakening her desire to be a mother. But it was not an easy transition. She was put on bed rest for the last six months of her first pregnancy, during which she felt like a “stupid hippo” and gained “fifty pounds and three chins in front of my soap opera.”

The value Lapid places on parenthood is also especially Israeli. During our interview, she told me, “Israel was established on the idea of a small nation surrounded by a lot of big nations, and we need to grow.” Israelis are constantly encouraged to have children. “Yeladim zeh simcha,” goes a popular saying, “children are happiness.” Lapid points out that Israel is one of the few countries in the world whose healthcare system covers fertility treatments beyond the first child. “We can go into the political issues about it,” she said to me, “from the beginning of Judaism, to the reaction to the Holocaust, to how many people we lost,” to the necessity to “build a new generation quickly.” Yet the conversation quickly moves from the theoretical to the personal. She tells me that her mother-in-law, writer Shulamit Lapid, reminded her that “we are the first generation of grandparents.” Because of the Holocaust, “none of us had grandparents,” and so, “grandparents are part of the family.”

According to a recent study by Bosmat Shalom-Tuchin in the Journal of International Women’s Studies, the support of grandparents, who often live close to their grandchildren and assist in daily tasks, helps make Israel an easier place for women to balance work and family. Shalom-Tuchin found that, unlike their counterparts in Europe and the United States, Israeli women tend to start their careers and families simultaneously. Lapid agrees with the study’s conclusions. In Israel, she says,

Kids are the first priority. There is a lot of support for mothers. There should be more, always. But I think that it is more common that kids go to day care from a very early age, until four in the afternoon. Women in Israel have been working for many years now. So, yes, there is a big support system.”

But Lapid’s message is that having a career and a family is what she calls a “process.” It can’t be done all at once. The main point of her columns, she tells me, is that there is a need to balance “your dreams and your family needs.” She is writing, she says, against the illusion that “all will be perfect and we will be perfect.”

Lapid’s mission on her U.S. book tour is to “show another Israel,” one whose people “deal with kids, family life, mother and father, how to keep the family together in this modern difficult world. For me, it is very important to export it.”

I first met Lapid during one of her attempts to do precisely that. She was getting ready to go onstage for a lunch discussion at the UJA-Federation of New York’s daylong “summit for women.” Entitled “i3: Insight Innovation Impact,” it was held at the New York Times Building in midtown Manhattan.

When we begin talking, I encourage Lapid to speak to me in Hebrew. We are just chatting at this stage, and I want her to feel as comfortable as possible. She refuses, telling me that it will be too difficult to speak in Hebrew and then switch back to English for her appearance.

As if on cue, a woman comes up while we’re talking and tells Lapid how much she enjoyed her speech to Congregation Kol Ami in Westchester the night before. The woman gushes about how her Israeli friends insisted she go and they were right. She tells Lapid that she was “so real” and “I loved listening to you.” Lapid listens graciously and thanks the woman as she rushes off to the podium to speak.

The fan turns out to be Hope Ziff, a marketing professional who scaled back her career when she had children. Now she runs a program at the JCC in Westchester called Mitzvah: It’s a Good Deed, in which she takes school children to visit nursing homes and orphanages in order to teach them about the concept of mitzvah. Clearly, Ziff is another woman who has reinvented her professional life in response to the challenges of raising a family. Another fan is Galit Beresteanu, an Israeli professional who has been living in the U.S. for over ten years. Beresteanu says, “I have been following Lihi’s writing from afar. Although she lives close to 10,000 kilometers from me, we have a lot in common. Her writing relates to my everyday multitasking, and balancing family and work needs.” This sense of commonality is what enables Lapid to get her message out.

On stage at the i3 Summit, Lapid is part of a panel of three speakers moderated by a female rabbi. Lapid is first and tells her audience that, in contrast to English, Hebrew words have different male and female forms. As a result, when one writes in Hebrew to women and for women, the language is different. Her column is the only one in an Israeli newspaper to address women directly in the female form. She speaks briefly about her book and then shares her message with the audience: That women are given the sense that they must fight for perfection, but as she puts it, “We don’t have to!” The audience breaks into spontaneous applause.

From there, we are off to the Jewish Channel, where I watch journalist Steven I. Weiss interview Lapid. He starts by introducing Lapid to the viewer. She stops him a few minutes in and says, “You’ve succeeded in saying my husband’s name five times in two minutes. Okay, that’s it. Is this about the book or about Yair?” Weiss apologizes for his gaffe and the show goes on, its host properly chagrined for the duration. I’m impressed by Lapid’s willingness to practice what she preaches and insist on sticking to the topic of her book rather than her politician husband, an interview the Jewish Channel would most probably not be able to land.

The Friday before we met in person, Lapid told me on the telephone she’d been interviewed earlier in the week and “after five minutes I said, ‘I am sorry,’” and ended the conversation. She explains the notion in Hebrew of “hochmat heder hamadrigot” or “stairwell wisdom”—you often think of what you should have said when you’re standing on the stairs after its all over. Lapid doesn’t want to think, “I should have said that,” so she constantly “exercises myself” to “say what I feel now, not to wait later and be sorry.” She wants to be able to speak out if she is in an uncomfortable situation, because it connects “to the whole notion of allowing myself not to be the last one,” not putting her own needs and desires after those of everyone else, both in the family and outside of it. Weiss remains uncomfortably patronizing throughout the interview, but Lapid stays on message, telling him that her column is different from other women’s because it is about empowerment. She discusses a recent column she wrote about women in an Israeli jail who produced a play about their lives. She describes how the letters she receives helped her book and how the comments women post on Facebook have come to replace them.

When Weiss asks how the situation of women in Israel has changed, Lapid recounts how she responded when fellow novelist Naomi Ragen told her that, in parts of Israel, women must sit at the back of buses. “Someone is making it up,” she said to Ragen, “it can’t be true.” To investigate, Lapid dressed as an Orthodox woman and went to Bnai Brak to take a bus. She was “shocked, I couldn’t go in,” and suspected that the bystanders could tell she was “not Orthodox.” But she also describes how the current Israeli government, the first since 1977 with no ultra-Orthodox parties, is part of an Israel “that is changing” and “a different way of looking at how Israel is supposed to look,” which could lead to a more progressive approach to Israeli society.

Weiss asks if women can “have it all.” Yes, Lapid says, women “can do it all but it takes more time. It is a fact that you don’t have to be perfect. Women are bad critics of ourselves. I want women to be able to say with this, ‘I’m not so good, it’s okay. My house isn’t totally spotless.’” She criticizes the misplaced sense of responsibility women often feel. “If someone says your daughter is beautiful,” she says, “a mother says ‘thank you’ and a dad says, ‘of course, yes she is.’” She concludes, “We can do it all, but slowly and easily.”

Most telling, though, is the moment when Weiss asks, “In what ways are Israeli women distinct?”

“We are less scared,” she replies, adding:

“The environment that we grow up in, every moment something can happen, so we focus more on the now. We can enjoy now, be happy now. What happened in the past, better to leave, because we can’t change. The future is totally not up to us. I invite women, and men too, to enjoy the moment.”

One senses that Sandberg, with her relentless stress on being better and doing more, would never utter such words.

One of the reasons may be that Lapid comes from a place where women have a strong sense of connection, both to each other and to the collective Jewish past. Lapid may be tapping into this when she explains why each chapter of her book opens with a Biblical quote: “The book is trying to gather into a certain circle in the middle, all Israelis, and the Bible is part of that. It is about the women in the Bible who breastfeed. Women today and mothers today are not disconnected from the past.” There are connections from “mother to daughter to granddaughter. Connecting.”

Is this something American Jewish women can learn from the Israeli model? A glance at the index to Sandberg’s book shows that, for all its research and statistics and talk of creating “Lean In circles,” the book is overwhelmingly concerned with bettering the careers of individuals, rather than any kind of collective change or connection. Hearing Lapid speak about connection and the Bible, I can’t help but think of journalist Anne Applebaum’s review in the New York Review of Books, which posits that Lean In is just another business book whose sole innovation is that it is geared toward women.

As we return to her hotel, Lapid is finally willing to speak to me in Hebrew. She is no longer worried that her English will suddenly disappear, as it did at an earlier event in Boston. She says that doing a book tour is something “I would never let myself do five years ago.” But because her children are now 17 and 18, on the cusp of army service, she has “no guilt now” about being away from home. She says that, after years spent nurturing her children, she is now able “to allow myself to take my place. Okay, it is my turn now.”

Lapid told me earlier, “I talk about a different kind of feminism, giving ourselves, not someone else giving us, the right to establish our dream. I want to do that. We are allowed to, and in the end the whole family is better when we are happy and feeling fulfilled.” She emphasized that “Guys are not part of this dialogue. Guys are happy when we are happy and willing to assist us when we say what we want.”

Over a glass of wine and a soft pretzel at the hotel bar, Lapid is reflective. “Women need to know how to ask for help—just to know that it is hard for everyone. I think they don’t know. So many women are suffering from baby blues. They know they are supposed to say it is the most wonderful thing that has happened to them. As much as we are getting ahead, a woman of 33 with an M.A., successful at work, married, a good economic situation,” is often limited to part-time work. “If you know that you’ll slow down in your career” while your children are young “and tell yourself, you will live more peacefully. This is a surprise to women.” She reminds me that “in the end it is tough for everyone. It is a bumpy road. Then it will be easier.”

She was eager to tell me about her book’s review in Publishers Weekly, which said “Individuals of all faiths will relate to the challenges inherent in marriage and raising children, and will certainly benefit from Lapid’s wake-up call to choose real-life happiness in a world of fairy-tale expectations.” Lapid is happy that her book may have universal appeal, because it allows her to “bring out another Israel, another side.”

I tell her that I want to give her some cash to donate to charity back in Israel, so that she will have a safe trip back. She is unfamiliar with the tradition: I explain that if she is a shlihat mitzva (“carrier of a mitzvah”) it will help ensure a safe flight. She assures me the money will go to a worthwhile cause. I lean in to give her a hug and feel grateful that a woman who has spent her life looking at people from behind a camera and on the page has opened herself up to me. Lapid certainly has the ability to let people know what she thinks, and empower them to know what they should think too.

And her message is a simple one: Women will not be empowered by “leaning in” more, or believing that by trying hard enough they can control every aspect of their lives. In her book, Sandberg notes that women hold “20 percent of seats in parliaments globally.” The political party Yesh Atid, led by Lihi Lapid’s husband Yair Lapid, has filled 40 percent of its Knesset seats with women. I know who I believe is having the greater impact on her country’s political agenda.

![]()

Banner Photo: Vardi Kahana / The Tower