What seemed to be a never ending trial of hundreds of Turkish officials accused of attempting to overthrow Ankara’s elected government culminated last Monday with verdicts. After five years the Turkish court in Silivri, a town in the outskirts of Istanbul, sentenced at least 18 people including General Ilker Basburg, the former commander of the armed forces to life in prison.

An Israeli intelligence researcher who observes Turkey evaluated the situation bluntly. “This is another major victory for the Prime Minister and his Islamist party in their march to consolidate their already extended power.”

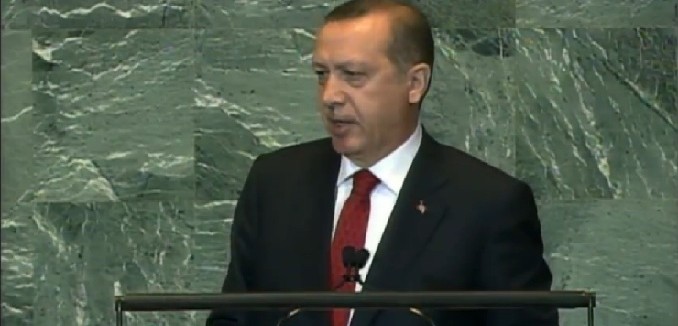

Altogether 275 defendants from major walks of Turkish secular life – current and former army officers, politicians, academics and journalists – were arrested in 2008 and charged with serious crimes. The charges included plotting to topple the government of the ruling Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) led by prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan; planning to create unrest to justify a military intervention against the government; planning to assassinate Erdogan; killing minority leaders; and planning to bomb mosques.

Sixty of the defendants received lighter sentences. The rest were acquitted.

The trial is a landmark in the history of the country. While many among Turkey’s 80 million citizens believe that the defendants conspired against the government, a significant portion of the population think that what emerged was a “show trial,” a travesty of justice and one more example of the authoritarian style of Prime Minister Erdogan. The prime minister has been blasted by more than one critic for conducting witch-hunts against his rivals.

The trials add to the Erdogan government’s record of systematically purging the military, the security services, the judiciary, and other important institutions. He has replaced rivals with his own loyalists.

When Mustafa Kemal Ataturk founded the modern Turkish republic nearly 100 years ago, the responsibility and authority for defending Turkey as a free, democratic, and secular society was delegated to the military. The military subsequently carried out coups in 1960, 1971, 1980 – and in 1997 pressured the government to resign – claiming that the moves were necessary to preserve the spirit of the constitution. Some saw them as pretexts for power grabs.

In June thousands of people in major Turkish cities turned out for massive anti-government demonstrations against the government’s autocratic inclinations. Some observers argue that one of the trial’s consequences could be another round of popular protest.

Whether or not protests erupt, Turkey is emerging from the trials as a more polarized society. On one side are the military, the secular, and the liberal segments of the population who adhere to the Kemalist legacy. On the other side are the newly emerging masses of Islamists who seem intent on turning the country a light theocracy.

[Photo: PBSNewsHour / YouTube]