Despite its small size, Israel has one of the world’s most prestigious and impactful international aid programs.

In the highlands of Ethiopia, the avocado is forging a unique bond between Ethiopian and Israeli farmers. Avocados are a profitable crop and people have an increasing taste for them. Americans are consuming more than six pounds per person annually, three times what they ate in 2000. The increasing demand means that many countries are seeking a piece of the action. One of them is Ethiopia, which is one of the top 20 producers in the world.

For Israel, this is a golden opportunity for agricultural collaboration. Yuval Fuchs, deputy head of MASHAV, Israel’s international development agency, recently returned from Ethiopia, where he saw the Israeli-Ethiopian partnership for himself. “One project we have is a wonderful cooperation with [the U.S. Agency for International Development] and it consists of six avocado nurseries,” says Fuchs. Avocado plants are sensitive to drought and weather conditions, and “it is not a known crop in the region…but there are optimal conditions. It is an intensive crop that if introduced correctly will be beneficial for the farmer.” According to Fuchs, the nurseries that Israel has supported in Ethiopia are producing 200,000 seedlings a year. These can be used to plant thousands of acres. “It’s a lot, in two to three years it can already yield [fruit], which is a strong contribution to farmers and exports,” he adds.

According to estimates from other countries, each acre can yield thousands of dollars in profits. In Ethiopia, which is among the poorer countries in the world—monthly salaries can be around $70 or less—these kinds of crops can make a huge difference. Fuchs says he saw both small and large farms succeeding with avocados. “We visited one farmer near Bahir Dar, a city in the north, and he planted 50 dunams [12 acres], and it is quite a lot for avocado, they just started learning techniques like grafting, drip irrigation, which is not yet very common. That will increase the yields. We have an expert on the ground located there.”

The success of projects like growing avocados in Ethiopia builds on a legacy of more than sixty years of MASHAV’s work. It was founded in 1957 under the guidance of then-Foreign Minister Golda Meir. Meir saw parallels between the Israeli experience and that of countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Much like those emerging states, Israel had to pioneer new methods of agriculture in order to make itself self-sufficient in a hostile environment.

This wasn’t just a question of “making the desert bloom,” which necessitated agricultural innovation, but also Israel’s strategic position as a small country surrounded by enemy states. Meir writes in her memoir My Life that, similar to Africa, Israel had to learn “how to irrigate, how to raise poultry, how to live together and how to defend ourselves. Independence had come to us, as it was coming to Africa, not served up on a silver platter.”

There was much that Israel could and wanted to give to African countries, she wrote, but at the time, there were few takers. North Africa’s Arab states were struggling for independence and were hostile to Israel. Volunteers to fight against Israel’s independence had come from Sudan, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. Jews were attacked in June of 1948 in Tripoli, Libya. As these North African countries gained independence, they joined the Arab League, which led the campaign against Israel internationally. But below the Sahara, as the desert gives way to the savannahs of Africa, Israel could pursue alliances with non-Arab African states.

Israeli Foreign Minister Golda Meir meets with Ghanaian Trade and Industry Minister Batsio Ghanese at her home in Jerusalem, 1957. Photo: Moshe Pridan / GPO

Sub-Saharan Africa’s independence struggle first succeeded in Ghana in 1957 and then Guinea in 1958. In 1960, 17 countries received independence from England and France, with dozens more coming in the next few years. Israel followed these independence movements closely, opening its first African embassy in Ghana in 1956 and becoming the fourth country to recognize Senegalese independence. Meir made a five-week trip across the continent in 1958. According to Eitan Bar-Yosef of Ben-Gurion University, Israel soon had experts at work in 33 African states “offering aid and technical knowledge in fields such as military training, regional planning, agriculture, medicine, legal work, and community services.” In The Rise and Fall of Israel’s Bilateral Aid Budget, Aliza Belman Inbal and Shachar Zehavi note that by the 1960s, MASHAV was “the largest department in Israel’s Foreign Ministry and Israel had, per capita, one of the most extensive technical assistance programs in the western world.”

This romance between Africa and Israel was short-lived. Following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, 25 sub-Saharan states severed relations with Israel at the behest of the Arab countries. Many members of the Organization of African Unity, which was founded in 1963, bought into the Soviet and Arab League-supported narrative that the war against Israel was part of the “global south” fighting against “imperialism,” and drastically reduced ties to Israel and MASHAV. The peace process that began in 1977 with Egypt, however, led to the renewal of ties, and Israel now maintains diplomatic relations with 40 countries in sub-Saharan Africa and has nine embassies on the continent, some of which represent interests in several countries.

A map of these relations is predictably divided along religious lines. The largely Muslim nations of North Africa, such as Chad, Mali, Sudan, and Niger, have no formal relations with Israel. Neither does Mauritania, which severed ties in 2010. Under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, however, relations with numerous countries in Africa became a priority. “The visit to Africa is very important in reinforcing and improving Israel’s standing in the international community,” then-Foreign Minister Avigdor Liberman said in 2009 before visiting Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana, Uganda, and Kenya. According to one report in Haaretz, Israeli exports to Africa totaled $3 billion that year, and the visit paired discussions about sustainable development with business, military, and strategic partnerships. Liberman built on his 2009 visit with another trip five years later, where he inaugurated a new direct flight route to Nairobi and celebrated 50 years of relations with Kenya and opened an agricultural training center in Rwanda and a palm oil production plant in Cote d’Ivoire. “I see great importance to investment in Africa, in the humanitarian, economic and political spheres,” he said. “There are many areas where Israel can help with aid and development: Agriculture, water management, medicine, combating terrorism, and more.”

Indeed, fighting terrorism is a key point of cooperation. In 2013, U.S. Undersecretary of the Treasury David Cohen told Reuters that West Africa was increasingly becoming a base of operations for Hezbollah. “There’s reason to think Hezbollah is not just collecting money but also using these outposts as places where they can plan and conduct activities,” he said. Hezbollah is especially active in areas where the Lebanese diaspora is located, including Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Gambia, and Senegal. The Hezbollah-Iranian connection threatens not only African states, but Israeli assets on the continent as well. Several Iranians were reportedly charged in Kenya on December 1, 2016 with plotting to attack the Israeli embassy. In 2002, terrorists attacked a Kenyan hotel frequented by Israelis on Chanukah eve and fired missiles at an Israel-bound flight.

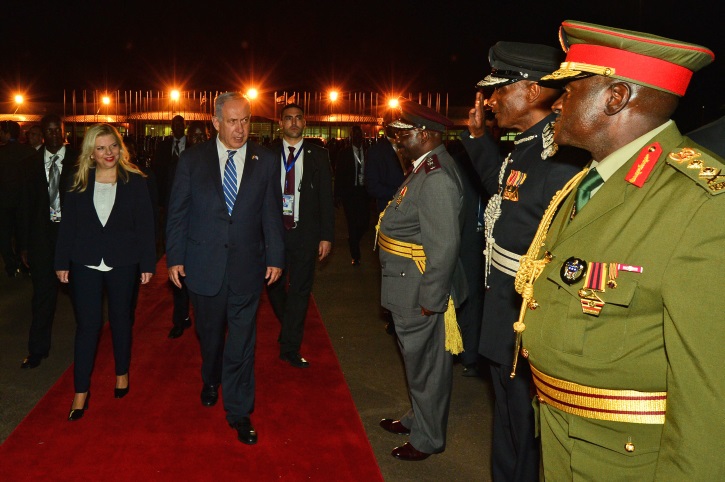

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his wife Sara during a visit to Entebbe, Uganda, July 4, 2016. Photo: Kobi Gideon / GPO

Israelis are by no means the only targets. Throughout Africa, Islamist terror has been on the rise. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb attacked a hotel in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso in January 2016 and aided an attack in Bamako, Mali in November 2015. Boko Haram has brought destruction to much of Nigeria. Al-Shabab has attacked Kenya, taken over part of Somalia, and carried out suicide bombings in Uganda.

Al-Shabab’s attacks on Uganda, most notably striking a World Cup watching party in 2010, weren’t the first time terrorism struck the country. In 1976, four hijackers from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine hijacked Air France Flight 139 and flew it to Uganda, which was then under the dictatorship of Idi Amin. In a daring raid, Israeli commandos freed 102 hostages from Entebbe International Airport and flew them to Israel. “This is a deeply moving day for me,” Netanyahu said at Entebbe in July 2016. “Forty years ago [Israeli commandos] landed in the dead of night in a country led by a brutal dictator who gave refuge to terrorists. Today we landed in broad daylight in a friendly country led by a president who fights terrorists.” He came to Entebbe to commemorate the raid and remember his brother Yonatan, who lost his life in the mission. The Prime Minister also visited Kenya, Rwanda, and Ethiopia, and has announced his intention to visit West Africa soon.

Israeli-African relations are anchored in Ethiopia and Kenya, and fan out from there across the continent. MASHAV has been a key part of these relations every step of the way. MASHAV’s website lists projects in in Ethiopia, Kenya, Ghana, Rwanda, South Sudan, Uganda, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Cameroon, and Togo.

Fuchs says the main thing that makes MASHAV special is that it is not a financing agency, but focuses on implementation. He explains that “Our strength is in capacity building,” that is, ensuring that the countries have the ability to continue with MASHAV-generated projects long after the Israelis have left. This is an important distinction from several larger countries engaged in international aid. Japan, Canada, Sweden, and France give more than a billion dollars in aid a year to Africa, and countries like Ethiopia, Tanzania, Kenya, and Nigeria receive billions from around the world. But despite massive transfers of wealth, these funds often prove ineffective in improving conditions on the ground.

In contrast, Israel’s skill since the 1950s has been in training and providing expertise. Paul Hirschson, Israel’s ambassador to Senegal, always stresses that the goal is “training the trainers.” That means bringing citizens from African states to Israel for training, or working alongside locals in the field.

Fuchs, who grew up in Haifa and was formerly a diplomat in the Czech Republic, Germany, Russia, and Georgia, says that the essential thing Israelis bring to the table is an appreciation for fieldwork. “If a country says education is a priority, or diabetes, then we work closely with what is coming in from the field,” he says. “We don’t stay far behind in the office. We want to see [our] diplomats and ambassadors out there in a nursery or hospital or school. We want to feel the ground and see it and be part of it.”

Israeli Ambassador to Senegal Paul Hirschson speaks at a press conference, September 2015. Photo: Israel au Sénégal / Facebook

On a trip to Senegal with Hirschson in the spring of 2016, I saw that up close. The Israeli embassy in Senegal is located in Dakar, a center of trade in West Africa. With its bustling downtown and epic 160-foot African Renaissance Monument, Dakar is a cultural hub. But it also has a tragic history of colonialism and slavery. For 300 years, slaves were exported from a small island off the coast called Goree. Visitors can see the dank cells where people were kept and the “door of no return” from which people were shipped to the New World. But from this tragic past has arisen a success story, a democracy in West Africa with a unique form of localized Islam and a colorful local culture.

“Agriculture is the anchor of what we are doing here,” says Hirschson. Doubling as Israel’s representative in Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, and Cape Verde, Hirschson deals with projects throughout the region. For instance, Israel recently helped create the only dialysis center in Sierra Leone, and trained doctors and nurses in Israel.

In March, Hirschson and I drove out to see what Israel has accomplished. The road out of Dakar’s urban landscape quickly turns into African grassland. Towering iconic baobab trees, with their giant trunks and little tufts of foliage, dot the landscape. Roads are lined with people selling agricultural products and farmers work the fields beside men herding goats and cows. At a small village named Touba-Toul, an hour or so east of Dakar, a gate leads to a pretty field. Rows of green onions are starting to grow and they stretch into the distance. Men come and go as they work in the fields. The project, in partnership with an Italian aid agency and the Senegalese agriculture ministry, brings Israeli expertise in drip irrigation to this dry climate.

Hirschson, who grew up in South Africa and has a background in high-tech, has a realistic and no-nonsense approach to development work. He doesn’t use diplo-speak where everything is generalizations and flowery talk. “I have my reservations about sustainable development work,” he says, having seen and heard about other foreign NGOs who come and go, throwing money at failed projects. In some countries, there has been 50 years of development aid with little to show for it. “The greatest difference we can make, the biggest bang for the buck, in the shortest amount of time, is by uplifting the small-hold family farmer,” says Hirschson. He contrasts this kind of sustainable development—such as training people in drip irrigation—with business partnerships. “We also have major commercial agricultural ventures across West Africa and they contribute to the economy. I argue that they are more important, but at best they generate low-skilled employment.”

Israel’s current project is to provide support for 4,000 farms in Senegal. More than 1,600 Senegalese farmers have been through a training course in drip irrigation that lasts 10 days. Israel’s professionals train groups of 25-30 people intensively, who then go on to train others in the local Wolof language. Hirschson argues that unlike some other aid organizations that may spend years doing unsuccessful development work, Israel wants to see real progress. “Israel doesn’t have the budget or capacity to throw good money after bad,” he says. “This is the foundation stone for Israel’s relations with West Africa, and certainly in Senegal.” However, he asserts, “We are on the cusp of a quantum leap forward in agricultural productivity; it could catch on like wildfire across the region.”

Throughout Senegal, government officials and locals are excited about Israel’s relations with the West African state. Senegal is one of the few Muslim-majority countries that has positive relations with Israel. Former ambassador Gideon Behar learned Wolof and is remembered fondly. Hirschson says the unique relationship with Muslim Africans is related to Israel’s ability to have a “different conversation” with sub-Saharan Africa. In Senegal, the Israeli embassy has provided sheep for the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha, which is called Tabaski here and takes a unique Senegalese form. Imams from Senegal have visited Israel, and the embassy has a good relationship with local religious leaders and the Islamic Sufi brotherhoods that dominate Senegalese culture. “More and more,” Hirschson says, “I meet with various religious leaders who have a special place in West African society and with secular people—civilian, political leadership—and they are acutely aware of the fact, more than I thought they would be, that we are not European. They identify us with the West but are acutely aware that we are not European.”

That means that although Muslims in Senegal and West Africa may have an affinity for the Islamic world and the Palestinian cause, they differentiate it from relations with Israel. Senegal chairs the UN Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People and has a seat on the Security Council. Despite positive relations with Israel, the country votes alongside Arab states in support of the Palestinians, most recently on UN Security Council Resolution 2334, which condemned Israeli settlement activity. This caused Israel to return Hirschson to Jerusalem for consultations.

However, the general picture in West Africa is a positive one. In July 2016, Foreign Ministry Director-General Dore Gold announced renewed ties with Guinea after a 49-year hiatus. “This is part of a process that is gaining momentum and is very important,” Netanyahu said at the time.

Israel has trained 67,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa, says Fuchs of MASHAV. More than 1,000 trainees from Africa came to Israel in 2016. Israel is constantly inviting delegations from Africa on study tours and partnering with other international and national aid agencies. “We had a conference with [the Economic Community of West African States] recently, in which 13 delegations out of 15 countries came to Israel, including agriculture ministers, and this was used as a platform for bilateral relations,” says Fuchs.

Like Hirschson, Fuchs stresses that the important thing for Israel is to be effective and avoid overstretching its limited resources. “In each country we work with, whether big or small, we have a clear development plan…a program that makes sense with elements that relate to each other and support each other,” Fuchs states.

For instance, in Swaziland, MASHAV is consulting on irrigation, and in Togo, Israeli doctors are doing cataract operations and training local doctors at the same time. In Kenya, one of Israel’s closest partners, MASHAV has several projects, most relating to water and education. One of them involves helping to reduce the pollution in Lake Victoria and improve water quality. In each case, Israel often partners with not only the local government but foreign aid organizations. Fuchs lists off Germans, Italians, and other collaborators who do the heavy lifting in investment and financing while Israel provides training and expertise.

One example of how Israel synergizes its aid on a variety of levels is in Tanzania’s new capital of Dodoma. Around 270 miles east of the former capital Dar es Salaam, Dodoma was supposed to be the new capital decades ago, but the move is still in progress. Israel is working on a trauma center that will accompany the transfer of government institutions. “It is a good example of how we attach things together and see them in one contact,” says Fuchs. “So there is the trauma center and another request to deal with emergency and disaster situations, so we will offer capacity building training related to disasters, which Israel has experience and expertise in.”

The overall picture of Israel’s relations with sub-Saharan Africa is that the dream Meir set forth in the 1950s of working with newly independent states has come full circle. The “different conversation” that Hirschson sees as unique to Jews and Africans due to shared histories is one that underpins this relationship. Whereas relations with Europe may have the baggage of historical anti-Semitism, and the Middle East has its own problems related to decades of hostility to the presence of a Jewish state, relations with sub-Saharan Africa are built on different pillars. MASHAV’s role in sustainable development and other aid work plays to Israel’s strengths and expertise. It also pairs well with increasing strategic and economic ties, and proves decisively that Israel now has a chance to play a positive role in Africa and form new alliances as a result.

![]()

Banner Photo: Seth J. Frantzman