A previously overlooked inscription in an ancient mosque near the city of Hebron has shed light on how, up to the mid-20th century, the Muslim world associated Jerusalem’s Temple Mount with the two Jewish sanctuaries that once stood there — a historical reality that has since been erased from the Palestinian narrative in an effort to undermine Jewish claims to the land.

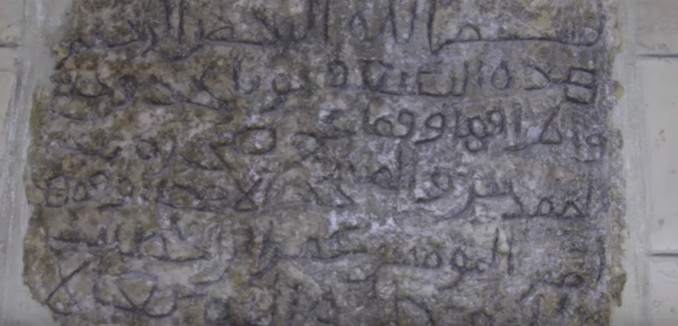

Israeli archaeologists last week presented a new study of a 9th or 10th century inscription from the Mosque of Umar in the village of Nuba, which is located in the mosque’s mihrab (a niche facing Mecca), The Times of Israel reported. The inscription reads: “In the name of God the merciful, the compassionate, this territory, Nuba, and all its boundaries and its entire area, is an endowment to the Rock of Bayt al-Maqdis and the al-Aqsa Mosque, as it was dedicated by the Commander of the Faithful, Umar ibn al-Khattab for the glory of Allah.”

The study’s authors, Assaf Avraham and Peretz Reuven, wrote that the references to the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock in the inscription, taken “together with the Hadith tradition and [Arabic] literature praising Jerusalem [from the 11th century], leads us to posit that the term Bayt al-Maqdis as it appears in the Nuba inscription… alludes directly to the Dome of the Rock.” Bayt al-Maqdis is a verbatim Arabic translation of “Bait Hamikdash,” which is how the First Temple is called in Hebrew.

There are further indications that, historically, Islamic scholars recognized the Temple Mount as a holy place of Jewish significance.

In Medieval times, Muslim traditions involving the Dome of the Rock “identified the mount again and again with David and Solomon’s temples” and “understood that the mount is the ancient temple rebuilt, the Quran is the true faith and the Muslims the true Children of Israel,” Avraham and Peretz observed.

Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad Shams al-Din al-Muqaddasi, a 10th century Muslim historian, also wrote that “in Jerusalem is the oratory of David and his gate; here are the wonders of Solomon and his cities,” and that the foundations of the Al-Aqsa Mosque “were laid by David.”

Similarly, Nasir-i Khusraw, an 11th century Persian writer, wrote in his description of the Temple Mount that it was “Solomon — upon him be peace! — who, seeing that the rock was the Kiblah point, built a mosque round about the rock, whereby the rock stood in the midst of the mosque, which became the oratory of the people.”

In its 1925 guide to the Temple Mount, the Islamic Waqf, which administers the site, called the fact that the Dome of the Rock was built on the site of Solomon’s Temple as being “beyond dispute.”

Even as late as 1951, Aref el-Aref — a historian and the Palestinian mayor of the Jordanian-occupied section of Jerusalem — wrote that “the ruins of Solomon’s Temple are under al-Aqsa” and that Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab built a mosque on top of the Temple’s ruins.

Despite this historical recognition of the Temple Mount’s Jewish history among Muslim scholars, “since the foundation of the State of Israel that narrative has been expunged from the Palestinian narrative,” the Times observed.

By the time that the Supreme Awqaf Council published “A Brief Guide to the Dome of the Rock and Haram al-Sharif” in 1965, the document made no mention of the Jewish temples.

Amid Palestinian rioting on the Temple Mount in opposition to Jewish visitation to the site — the holiest in Judaism and the third holiest in Islam — the Palestinian Authority-appointed Mufti of Jerusalem claimed in October 2015 that the Temple Mount hosted a mosque “since the creation of the world,” and that it never housed a Jewish temple.

Sheikh Muhammad Ahmad Hussein alleged that the site was a mosque “3,000 years ago, and 30,000 years ago” and has been “since the creation of the world.”

“This is the Al-Aqsa Mosque that Adam, peace be upon him, or during his time, the angels built,” he said.

Attempts to undermine Jewish claims to the Temple Mount, which The New York Times noted last year have led many Palestinians to “increasingly [express] doubt that the temples ever existed,” is a phenomenon that Dr. Dore Gold, former Israeli ambassador to the United Nations and former director-general of the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, described as “Temple denial.” David Hazony, editor of The Tower, wrote in 2007 that “Palestinian leaders, writers, and scholars have embarked on a campaign of intellectual erasure […] aimed at undermining the Jewish claim to any part of the land.”

Temple denial has been central to two recent Arab-sponsored UNESCO resolutions, which have erased the extensive Jewish historical connection to the Temple Mount. A Boston Globe editorial on Tuesday warned that such “malicious distortions of history” have in the past “triggered wars and incited bloodshed.” Eylan Aslan-Levy wrote in The Tower on Monday that the resolutions, which seek “to render Israeli sovereignty over the Old City utterly illegitimate, do the most damage by prejudging how the international community should approach the question of the holy sites in any future accord.”

Petra Marquardt-Bigman similarly wrote in The Tower after the first resolution was passed last month that UNESCO “has rewarded almost a century of Palestinian intransigence and deadly incitement.”

[Photo: Assaf Avraham / YouTube ]